Introduction

Intracardiac shunts are abnormal pathways for blood flow in the heart that form in addition to or in place of normal pathways. They are congenital heart defects resulting from abnormal embryologic development. The resultant blood flow is pathological and often causes significant changes in normal physiology. Intracardiac shunts are a spectrum of disorders that could range in presentation from being asymptomatic to fatal. The 2 big categories of intracardiac shunts are cyanotic and cyanotic. Cyanotic shunts impair blood oxygenation by the pulmonary system and result in cyanosis. Acyanotic shunts do not impair lung blood flow, and the oxygenation process is intact. Following are different types of cyanotic and cyanotic shunts.

- Acynotic shunts: Atrial septal defect, ventricular septal defect, patent ductal arteriosus

- Cyanotic shunts: Tetralogy of Fallot, truncus arteriosus, total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR), pulmonary atresia with ventricular septal defect, tricuspid atresia, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, transposition of great arteries, double-outlet right ventricle

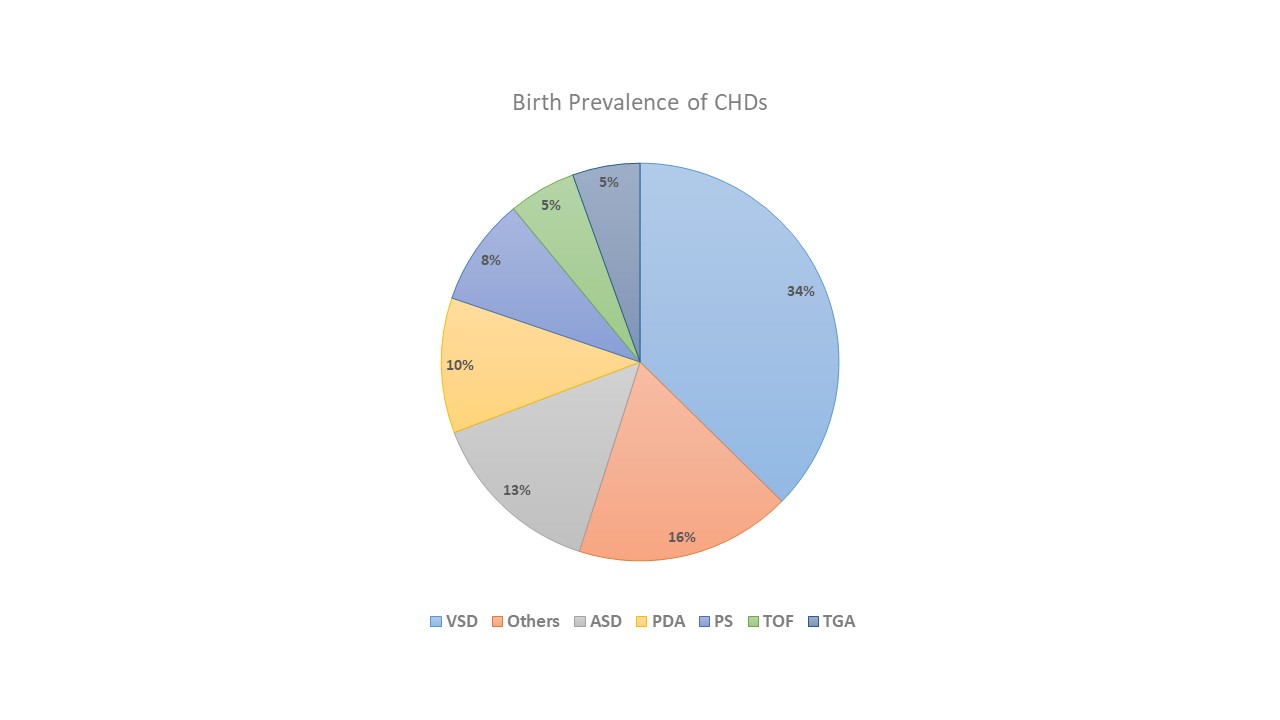

The prevalence of different types of these shunts is shown in the pie chart (see Graph. Birth Prevalence of CHDs).[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of Intracardiac shunt formation is multifactorial and combines genetic and external factors. Genetic factors include chromosomal deletions, trisomies, and single-gene mutations. For example, 40 to 50% of those born with trisomy 21 or Down syndrome have ASD, VSD, TOF, or TGA.[2] Maternal factors that increase the risk for intracardiac shunt formation are pregestational diabetes, marijuana use, rubella, ibuprofen, influenza, febrile illness, and vitamin A exposure.[3]

Epidemiology

Intracardiac shunts are the most common congenital heart defects. One in 8 newly born infants worldwide has some congenital heart anomaly. The prevalence of congenital heart defects varies with geography. Asia has the highest prevalence, with 9.3 cases reported for every 1,000 live births, and the least prevalence was noticed in Africa, with 1.3 cases reported for every 1,000 live births. North America has 6.9 cases per 1,000 live births. The difference in prevalence could also be attributed to the better availability of diagnostic modalities in certain parts of the world than in others. In the US, the prevalence of congenital heart defects is slightly higher in whites and Hispanics than in the black population. Overall, female predominance was seen in the US, with 8.03 females affected compared to 7.67 males for every 1,000 live births.[4] Due to the invention of better medical and surgical therapies, the survival of patients with congenital heart diseases is increasing, which also increases their prevalence in the adult population.[5]

Pathophysiology

Intracardiac shunts are anatomic defects that occur from derangements in the embryologic development of the heart, mainly in the first trimester of pregnancy. Fetal heart development occurs from the mesoderm. It is a complex process where a single heart tube is initially formed, which later develops into 4 chambers with separate inflow and outflow tracts by cell migration and looping of the structures.[6] Incomplete separation of right and left-sided structures leads to defects like ASD, VSD, and PDA. Since left-sided cardiac pressures are higher, defects in atrial or ventricular septums or patency of ductus arteriosus lead to blood shunting into the right side where pressures are lower. Since all deoxygenated blood from systemic circulation makes its way to the lungs, oxygenation is not a problem. Shunting only sends additional blood into the lungs; this blood is already oxygenated. Therefore, these lesions are called acyanotic shunts.

Small defects can close by themselves with time; however, larger defects can sometimes require surgical intervention. Left to right shunts are often asymptomatic in childhood; however, symptoms can appear in adolescence and adulthood. Presentation often includes shortness of breath, exercise intolerance, and easy fatigability. In these defects, the right side of the heart receives more blood, which causes pulmonary hypertension over time in some patients. A rare complication of these shunts is Eisenmenger syndrome, in which shunt reversal occurs due to severe pulmonary hypertension to the point that right-sided pressures exceed left-sided pressures. This syndrome causes cyanosis and carries a high mortality.[7]

The other group of intracardiac shunts is called cyanotic shunts. In these disorders, anatomic defects impede the flow of deoxygenated blood to the lungs. Oxygenation is impaired in these disorders, and partial pressure of oxygen in arterial circulation is low. Tissues do not get enough oxygen supply, and characteristic bluish skin discoloration, called cyanosis, is seen. Cyanotic lesions are associated with significant morbidity and mortality and typically present early after birth; however, small lesions could be minimally cyanotic or even completely asymptomatic at first. Symptoms include cyanosis, clubbing of fingers and toenails, dyspnea, poor weight gain, hemoptysis, and recurrent infections.[8] A classic phenomenon historically seen in patients with cyanotic spells was squatting, which increases systemic vascular resistance, thereby increasing pulmonary flow. This improves oxygen and relieves symptoms. Squatting is not seen as common now due to early diagnosis and improved therapeutic interventions.

History and Physical

Congenital disorders are present at the time of birth, and history is often not practicable. However, history is important as a child grows up and can talk. Patients should be asked for clinical symptoms, including dyspnea, exercise capacity, recurrent infections, skin discoloration, hemoptysis, presyncope or syncope, and pedal edema when possible. Physical examination is critical and often is the only indication of the disease. It should include thorough inspection, palpation, and auscultation. Inspection should be conducted for cyanosis, nail clubbing, growth stunting, jugular venous distension, pedal edema, and breathing difficulty. Palpation should be done to notice the apex beat's thrill, heave, or displacement. Characteristic murmurs are present in different shunts at different locations, aiding diagnosis. Typical murmurs heard are fixed widely split S2 with ejection systolic murmur at the pulmonary area in ASD, holosystolic murmur at the left lower sternal border in VSD, and continuous machinery murmur in PDA. The murmur in TOF would be due to the pulmonic stenosis and not due to the concomitantly present VSD, and a systolic ejection sound is heard at the left upper sternal border.[9] Murmurs can often be unclear, and a formal echocardiogram should be obtained to evaluate a pathological murmur.

Evaluation

After the initial history and physical examination, further workup should be done as warranted. The extent of evaluation for intracardiac shunts depends on a case-by-case basis. It could include blood testing, electrocardiogram (EKG), echocardiogram, chest x-ray, CT scan, and cardiac catheterization (see Image. Transesophageal Echocardiogram). EKG could indicate signs of pulmonary hypertension from right ventricular hypertrophy, right axis deviation, and right atrial enlargement. Right ventricular hypertrophy shows tall R wave in V1, dominant S wave in leads V5 and V6 and can also produce p pulmonale and right ventricular strain pattern on EKG that could be evidenced by ST depressions and T wave inversions in the right precordial (V1-V4) and inferior (II, III, aVF) leads.[10]

A chest X-ray could show characteristic heart shapes in different defects. TOF could make the heart boot-shaped on CXR, TAPVR could show a snowman-shaped heart, and TGA could give the heart an "egg-on-string" appearance.[11] Blood work could show reactive polycythemia in cyanotic defects, indicating the severity of hypoxemia. Cardiac catheterization is not typically needed for diagnostic purposes but should be done once the surgical intervention is planned. It gives accurate pressures in heart chambers. Induction of oxygen or nitric oxide could be done in the pulmonary system to see vascular reactivity, which could help decide if the patient is a candidate for surgical intervention or pulmonary vasodilator therapy.

Treatment / Management

Management of a shunt depends on the disease type and ranges from simple clinical observation, medical therapy, and lifestyle modification to surgical intervention. Small noncyanotic shunts can often be clinically observed. Large left-to-right shunts do need closure to avoid the development of complications. Cyanotic shunts are associated with higher morbidity and mortality and often require surgical intervention for correction. For example, TOF needs surgical intervention, often done in stages. In the first phase, a connection is created between the subclavian artery and the pulmonary artery called the Blalock-Tussing shunt.

Some surgeons choose not to perform this procedure and directly proceed to the next steps. The superior vena cava is connected to the right pulmonary artery via the Glenn shunt in the second phase. In the third phase, the inferior vena cava is connected to the pulmonary artery in a Fontan procedure. In cyanotic conditions, vessel thrombosis could occur due to increased hematocrit from reactive polycythemia. Phlebotomy is done on a case-by-case basis to correct the hematocrit. For female patients desiring to get pregnant, a discussion should be held with an obstetrician before conception to discuss the plans. Some disorders are associated with high obstetric mortality, and pregnancy is not advised.[12]

Differential Diagnosis

Careful evaluation should be done as clinical features overlap between different types of intracardiac shunts and can also mimic extracardiac disease processes. Cyanotic intracardiac shunts could mimic pulmonary, neurologic, and infectious diseases. Transient tachypnea of newborns, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, pulmonary hypoplasia, laryngotracheomalacia, vocal cord paralysis, neonatal myasthenia gravis, spinal muscular atrophy, infantile botulism, and pneumonia should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Prognosis

The prognosis depends on the particular type of shunt. Noncyanotic shunts carry remarkably better prognosis than cyanotic shunts. Small lesions can often close spontaneously or could remain asymptomatic for life. Large lesions need closure to avoid complications. Once severe pulmonary hypertension has developed, the prognosis worsens, and heart-lung transplantation is often warranted, which is not widely available. Severe cyanotic lesions present soon after the birth, and often, there is no chance of survival without timely surgical intervention.

Complications

Complications of intracardiac shunts include failure to thrive, recurrent infections, pulmonary hypertension, right heart failure, Eisenmenger syndrome, infective endocarditis, dysrhythmias, and death. However, not all shunts result in complications, and most are benign.

Deterrence and Patient Education

A combination of modifiable and nonmodifiable factors causes intracardiac shunts. Before conception, family physicians and obstetricians should counsel the mothers about safe prenatal approaches to minimize the incidence of such diseases. These approaches include but are not limited to, better diabetes control, avoiding teratogenic substances like retinoids and ibuprofen, and steering clear of recreational drugs. As kids grow into adolescence and start understanding things, they should be educated compassionately and realistically about their conditions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing intracardiac shunts requires an interprofessional team approach; while pediatricians and cardiologists are mostly at the frontlines for the diagnosis and treatment plans, it is important to consult with multiple disciplines, including cardiothoracic surgeons, physical therapists, bedside nursing staff, and psychologists, to improve overall outcomes, patient safety, and enhance team performance. Diagnostic studies are required for both diagnosis and operative planning. This requires an EKG, echocardiogram, chest X-ray, CT scan, and cardiac catheterization, comprising a coordinated effort between multiple teams. This ultimately results in more accurate diagnoses, better surgical outcomes, and more patient and family satisfaction.

Media

(Click Video to Play)

Transesophageal Echocardiogram. Transesophageal echocardiogram, before and after patent foramen ovale closure, revealing delayed intracardiac shunting and hypoxemia after massive pulmonary embolism.

Weig T, Dolch M, Frey L, et al. Delayed intracardial shunting and hypoxemia after massive pulmonary embolism in a patient with a biventricular assist device. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:133.

doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-133.

References

van der Linde D, Konings EE, Slager MA, Witsenburg M, Helbing WA, Takkenberg JJ, Roos-Hesselink JW. Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2011 Nov 15:58(21):2241-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.08.025. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22078432]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePierpont ME, Basson CT, Benson DW Jr, Gelb BD, Giglia TM, Goldmuntz E, McGee G, Sable CA, Srivastava D, Webb CL, American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Genetic basis for congenital heart defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Congenital Cardiac Defects Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2007 Jun 12:115(23):3015-38 [PubMed PMID: 17519398]

Jenkins KJ, Correa A, Feinstein JA, Botto L, Britt AE, Daniels SR, Elixson M, Warnes CA, Webb CL, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young. Noninherited risk factors and congenital cardiovascular defects: current knowledge: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young: endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. Circulation. 2007 Jun 12:115(23):2995-3014 [PubMed PMID: 17519397]

Gilboa SM, Devine OJ, Kucik JE, Oster ME, Riehle-Colarusso T, Nembhard WN, Xu P, Correa A, Jenkins K, Marelli AJ. Congenital Heart Defects in the United States: Estimating the Magnitude of the Affected Population in 2010. Circulation. 2016 Jul 12:134(2):101-9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.019307. Epub 2016 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 27382105]

Hoffman JI, Kaplan S, Liberthson RR. Prevalence of congenital heart disease. American heart journal. 2004 Mar:147(3):425-39 [PubMed PMID: 14999190]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGittenberger-de Groot AC, Bartelings MM, Poelmann RE, Haak MC, Jongbloed MR. Embryology of the heart and its impact on understanding fetal and neonatal heart disease. Seminars in fetal & neonatal medicine. 2013 Oct:18(5):237-44. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2013.04.008. Epub 2013 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 23886508]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChaix MA, Gatzoulis MA, Diller GP, Khairy P, Oechslin EN. Eisenmenger Syndrome: A Multisystem Disorder-Do Not Destabilize the Balanced but Fragile Physiology. The Canadian journal of cardiology. 2019 Dec:35(12):1664-1674. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2019.10.002. Epub 2019 Oct 10 [PubMed PMID: 31813503]

Karl TR, Stocker C. Tetralogy of Fallot and Its Variants. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 2016 Aug:17(8 Suppl 1):S330-6. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000831. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27490619]

Wang J, You T, Yi K, Gong Y, Xie Q, Qu F, Wang B, He Z. Intelligent Diagnosis of Heart Murmurs in Children with Congenital Heart Disease. Journal of healthcare engineering. 2020:2020():9640821. doi: 10.1155/2020/9640821. Epub 2020 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 32454963]

Nikus K, Pérez-Riera AR, Konttila K, Barbosa-Barros R. Electrocardiographic recognition of right ventricular hypertrophy. Journal of electrocardiology. 2018 Jan-Feb:51(1):46-49. doi: 10.1016/j.jelectrocard.2017.09.004. Epub 2017 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 29046220]

Haider EA. The boot-shaped heart sign. Radiology. 2008 Jan:246(1):328-9 [PubMed PMID: 18096546]

Downing TE,Kim YY, Tetralogy of Fallot: General Principles of Management. Cardiology clinics. 2015 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 26471818]