Introduction

Oxygen saturation is an essential element in the management and understanding of patient care. Oxygen is tightly regulated within the body because hypoxemia can lead to many acute adverse effects on individual organ systems. These include the brain, heart, and kidneys. Oxygen saturation measures how much hemoglobin is bound to oxygen compared to how much hemoglobin remains unbound. At the molecular level, hemoglobin consists of 4 globular protein subunits. Each subunit is associated with a heme group. Each hemoglobin molecule subsequently has 4 heme-binding sites readily available to bind oxygen. Therefore, hemoglobin can carry up to 4 oxygen molecules during oxygen transport in the blood. Due to the critical nature of tissue oxygen consumption in the body, it is essential to monitor current oxygen saturation. A pulse oximeter can measure oxygen saturation (see Image. Pulse Oximeter). It is a noninvasive device placed over a person's finger. It measures light wavelengths to determine the ratio of the current levels of oxygenated hemoglobin to deoxygenated hemoglobin. The use of pulse oximetry has become a standard of care in medicine. It is often regarded as a fifth vital sign. As such, medical practitioners must understand the functions and limitations of pulse oximetry. They should also have a basic knowledge of oxygen saturation.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

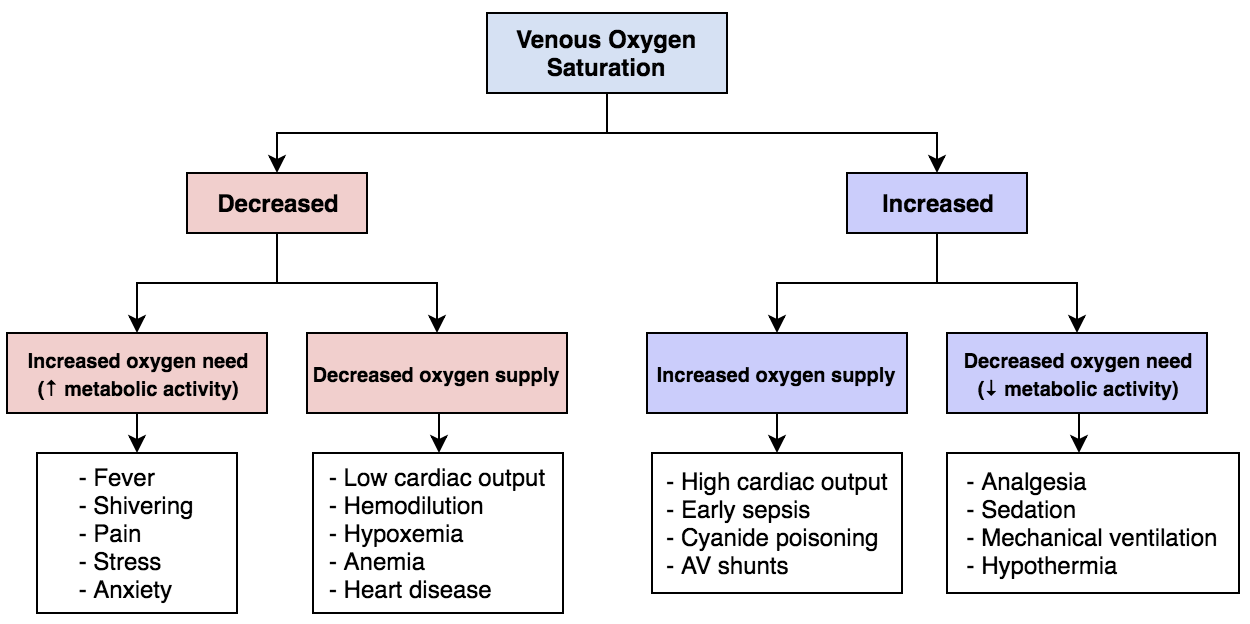

One definition of oxygen consumption within the body is the product of arterial-venous oxygen saturation differences and blood flow (see Figure. Mixed Venous Oxygen Saturation). The body consumes oxygen partially through aerobic metabolism. In this process, oxygen converts glucose to pyruvate, liberating 2 molecules of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). An important aspect of this process is the oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve. In the blood, hemoglobin binds free oxygen rapidly to form oxyhemoglobin, leaving only a small percentage of free oxygen in the plasma. The oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve plots the percent saturation of hemoglobin as a function of the partial pressure of oxygen (PO2). At a PO2 of 100 mmHg, hemoglobin is 100% saturated with oxygen, meaning all 4 heme groups are bound. Each gram of hemoglobin is capable of carrying 1.34 mL of oxygen. The solubility coefficient of oxygen in plasma is 0.003. This coefficient represents the volume of oxygen in mL that dissolves in 100 mL of plasma for each 1 mmHg increment in the PO2. A formula then calculates the oxygen content so that Oxygen Content = (0.003 × PO2) + (1.34 × Hemoglobin × Oxygen Saturation). This formula demonstrates that dissolved oxygen is a sufficiently small fraction of total oxygen in the blood; therefore, the oxygen content of blood can be considered equal to the oxyhemoglobin levels.[1]

As PO2 decreases, the percentage of saturated hemoglobin also decreases. The oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve has a sigmoidal shape due to the binding nature of hemoglobin. With each oxygen molecule bound, hemoglobin undergoes a conformational change to allow subsequent oxygens to bind. Each oxygen that binds to hemoglobin increases its affinity to bind more oxygen, meaning the affinity for the fourth oxygen molecule is the highest.

In the lungs, alveolar gas has a PO2 of 100 mmHg. However, due to the high affinity for the fourth oxygen molecule, oxygen saturation remains high even at a PO2 of 60 mmHg. As the PO2 decreases, hemoglobin saturation eventually falls rapidly; at a PO2 of 40 mmHg, hemoglobin is 75% saturated. Meanwhile, at a PO2 of 25 mmHg, hemoglobin is 50% saturated. This level is referred to as P50, where 50% of heme groups of each hemoglobin have a molecule of oxygen bound. The nature of oxygen saturation becomes increasingly important in light of the effects of right and left shifts. A variety of factors can cause these shifts.

A right shift of the oxygen saturation curve indicates a decreased oxygen affinity of hemoglobin, allowing more oxygen to be available to tissues.[2] The mnemonic, "CADET, face Right!" can help remember factors leading to a right shift. "CADET" stands for PCO2, acid, 2,3-diphosphoglycerate, exercise, and temperature. The hemoglobin dissociation curve shifts right with an increase in each factor.

A left shift of the oxygen saturation curve indicates an increase in hemoglobin's oxygen affinity, which reduces oxygen availability to the tissues. Factors that cause a left shift in the oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve include decreases in temperature, PCO2, acidity, and 2,3-bisphosphoglyceric acid, formerly named 2,3-diphosphoglycerate.

Indications

Due to the noninvasive nature and relative importance of pulse oximetry readings, very few situations do not indicate its use. Pulse oximetry can provide a rapid tool to assess oxygenation accurately. It is particularly useful in emergencies for this reason. Cyanosis may not develop until oxygen saturation reaches about 67%. As such, pulse oximetry is extremely useful because the signs and symptoms of hypoxemia may not be visible on physical examination.

Indications for pulse oximetry include any clinical setting where hypoxemia may occur. These settings include patient monitoring in emergency departments, operating rooms, emergency medical services systems, postoperative recovery areas, endoscopy suites, sleep, and exercise laboratories, oral surgery suites, cardiac catheterization suites, facilities that perform conscious sedation, labor and delivery wards, interfacility patient transfer units, altitude facilities, aerospace medicine facilities, and even patients' homes.[3]

Contraindications

Pulse oximetry is rarely contraindicated, but understanding its limitations is helpful. A relative contraindication may be the need to measure pH, PaCO2, total hemoglobin, and abnormal hemoglobin, as in the setting of carbon monoxide toxicity. It is also essential to monitor the probe's location for changes in skin conditions, such as blisters or damage to the nail bed. Patients with burns may also require the probe to be repositioned every 2 to 4 hours.

Equipment

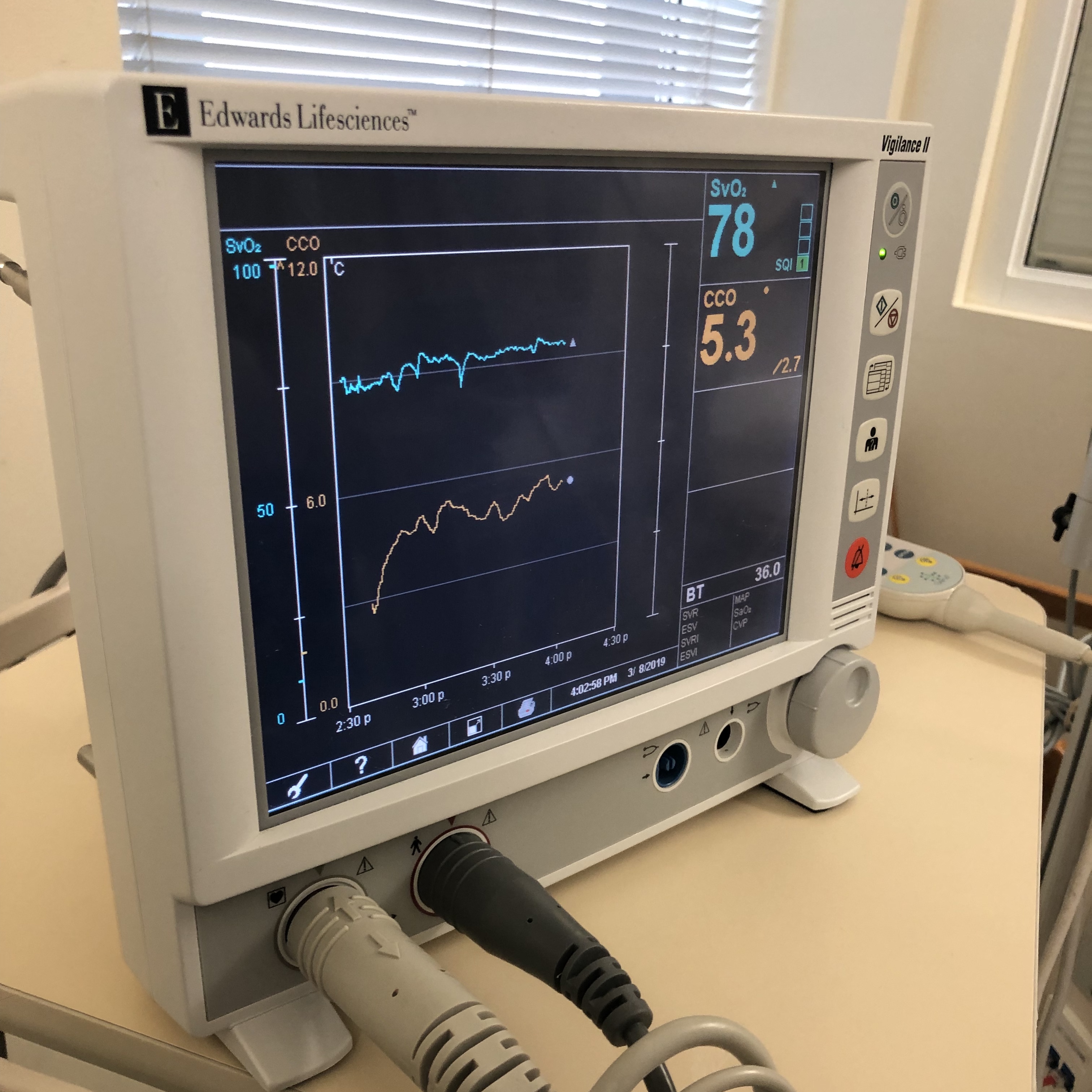

The pulse oximeter consists of a probe containing LEDs and a photodetector. The LEDs emit light at fixed, selected wavelengths. The photodetector measures the quantity of light transmitted through a selected vascular bed, such as a fingertip or earlobe. Pulse oximetry uses the Beer-Lambert law of light absorption. This law describes how light is absorbed when it passes through a clear solvent, such as plasma, that contains a solute that absorbs light at a specific wavelength, such as hemoglobin.[4] The absorption spectra of oxygenated and reduced hemoglobin differ. For this reason, arterial blood appears red, while venous blood appears blue. However, because living tissue absorbs light, it is difficult to determine the ratio of saturation of hemoglobin in the body. The oximeter probe overcomes this difficulty by emitting light pulses, 1 red and 1 infrared. A detector is placed opposite the lights on the other side of the tissue. The diodes switch on and off in rapid sequence, and the detector measures the differences. The measurements feed into an algorithm in a microprocessor where the oxyhemoglobin saturation is calculated and eventually displayed to the user (see Image. Monitor Shows Mixed Venous Oxygen Saturation Value).[3]

Personnel

All medical personnel should train with a basic understanding of pulse oximetry. Advanced users find it helpful to understand the relationship between pulse oximetry readings and blood hemoglobin concentrations and how they are affected by the oxygen-hemoglobin dissociation curve.

Preparation

When preparing to apply the pulse oximeter, the most important consideration is placing the monitor where the light can shine through to the detector. Consider multiple factors before placing the pulse oximeter. Patients should remove nail polish and the finger wiped with an alcohol preparation. Examine the finger for other objects, such as excess pigmentation. For example, tattoos may block light as it passes through the tissue. High-intensity ambient light has also been shown to interfere with the accuracy of pulse oximetry readings. Before application, the rubber shield on the pulse oximeter should be intact to help reduce ambient light input.

Technique or Treatment

After verifying the appropriate placement site, place the pulse oximeter so that the light penetrates through the tissue and is picked up by the detector. The probe must fit the finger well when placing the pulse oximeter on a fingertip. It should not be too tight or too loose. Take extra caution to ensure the probe does not restrict circulation to the digit, as this may provide an inaccurate reading. There are also probes made for the earlobe. In an emergency, the pulse oximeter may be placed on the fingertip sideways as nail polish or pigment may obstruct the light.

Complications

Complications from using a pulse oximeter are rare. However, it is necessary to be aware of the probe site as blisters or nail damage may occur with extended use. Tissue injury may also occur in the setting of incompatible probes or during a substitution in the form of electrical shock or burns. It is also essential to know how to improve the measurements of pulse oximeters.

Possible ways to improve pulse oximeter signals include:

- Warm and rub the skin

- Apply a topical vasodilator

- Try a different probe site, especially the ear

- Try a different probe

- Use a different machine [3]

Factors that may reduce the accuracy of pulse oximeter signals include:

- Nail polish [5]

- Pigmentation of the skin

- High-intensity ambient lighting

- Excessive patient movement or motion artifacts

- Decreased perfusion

- Presence of abnormal hemoglobin, carboxyhemoglobin

- Intravascular dyes

- Reduced accuracy with saturations below 83%

One significant risk of using a pulse oximeter is the possibility of treating an incorrect reading as accurate. False-negative results for hypoxemia and false-positive results for normoxemia or hypoxemia can occur. In these situations, a patient may receive inappropriate treatment, leading to harm.

False normal or high readings can occur in multiple different settings. Carboxyhemoglobin absorbs light at 660 nanometers, roughly the same as oxyhemoglobin. Thus, in situations where carboxyhemoglobin is high, a false normal reading may occur.[6] When glycohemoglobin A1c levels are greater than 7%, such as in patients with type 2 diabetes, arterial oxygen saturation may be overestimated.[7] These situations may require an arterial blood gas to determine oxygen saturation accurately. It is also necessary to consider the clinical diagnosis when evaluating a patient with hypoxemic symptoms, as in the case of carbon monoxide toxicity.

False low readings can also occur in multiple settings. Below are some situations that may cause falsely low readings to occur.

- Methemoglobinemia

- Sulfhemoglobinemia

- Sickle hemoglobin

- Abnormal inherited forms of hemoglobin [8]

- Severe anemia

- Venous congestion

Clinical Significance

The human eye's ability to detect hypoxemia is poor. The presence of central cyanosis, blue coloration of the tongue and mucous membranes, is the most reliable predictor; it occurs at an oxyhemoglobin saturation of about 75%.[3] Pulse oximetry provides a convenient, noninvasive method to measure blood oxygen saturation continuously. It can also help to eliminate medical errors. Pulse oximetry has a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 90% when detecting hypoxia at a 92% oxygen saturation threshold.[9]

There is no set standard of oxygen saturation where hypoxemia occurs. The generally accepted standard is that a normal resting oxygen saturation of less than 95% is considered abnormal.[10] Therefore, observing patients for the clinical markers of hypoxemia remains vital. The brain is the most sensitive organ, and visual, cognitive, and electroencephalographic changes develop when the oxyhemoglobin saturation is less than 80% to 85%. It is unclear whether there are long-term deficits from hypoxemia. Patients with nocturnal hypoxemia do not seem to develop life-threatening complications despite abnormally low oxygen saturation.[3]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

All healthcare workers should be familiar with pulse oximetry. Pulse oximetry is an accurate measurement of the patient's overall oxygen saturation. While few studies have demonstrated a decrease in mortality from using pulse oximetry, it provides more benefit than harm. Clinicians should be aware of the limitations and errors associated with pulse oximetry. They should use their best clinical judgment when deciding whether further workup is needed. In the case of hypoxemia, a physician should always consider whether an arterial blood sample would provide a more accurate measure of oxygen saturation than pulse oximetry.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Kaufman DP, Kandle PF, Murray IV, Dhamoon AS. Physiology, Oxyhemoglobin Dissociation Curve. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29762993]

Clause D, Detry B, Rodenstein D, Liistro G. Stability of oxyhemoglobin affinity in patients with obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome without daytime hypoxemia. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md. : 1985). 2008 Dec:105(6):1809-12. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.90860.2008. Epub 2008 Oct 23 [PubMed PMID: 18948445]

Hanning CD, Alexander-Williams JM. Pulse oximetry: a practical review. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 1995 Aug 5:311(7001):367-70 [PubMed PMID: 7640545]

Bongard F, Sue D. Pulse oximetry and capnography in intensive and transitional care units. The Western journal of medicine. 1992 Jan:156(1):57-64 [PubMed PMID: 1734600]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHinkelbein J, Koehler H, Genzwuerker HV, Fiedler F. Artificial acrylic finger nails may alter pulse oximetry measurement. Resuscitation. 2007 Jul:74(1):75-82 [PubMed PMID: 17353079]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGrace RF. Pulse oximetry. Gold standard or false sense of security? The Medical journal of Australia. 1994 May 16:160(10):638-44 [PubMed PMID: 8177111]

Pu LJ, Shen Y, Lu L, Zhang RY, Zhang Q, Shen WF. Increased blood glycohemoglobin A1c levels lead to overestimation of arterial oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovascular diabetology. 2012 Sep 17:11():110. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-11-110. Epub 2012 Sep 17 [PubMed PMID: 22985301]

Sarikonda KV, Ribeiro RS, Herrick JL, Hoyer JD. Hemoglobin lansing: a novel hemoglobin variant causing falsely decreased oxygen saturation by pulse oximetry. American journal of hematology. 2009 Aug:84(8):541. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21452. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19536848]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee WW, Mayberry K, Crapo R, Jensen RL. The accuracy of pulse oximetry in the emergency department. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2000 Jul:18(4):427-31 [PubMed PMID: 10919532]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAmerican Thoracic Society, American College of Chest Physicians. ATS/ACCP Statement on cardiopulmonary exercise testing. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2003 Jan 15:167(2):211-77 [PubMed PMID: 12524257]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence