Introduction

Malignant eyelid lesions can be identified by the eye care provider, primary care provider, or dermatologist during a routine exam. The most common malignancies of the eyelid include basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, sebaceous cell carcinoma, melanoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma.

Other eyelid malignancies exist, but these are rare and beyond the scope of this article. It is crucial to remember that any cutaneous malignancy can occur in the periocular region, and physicians should perform a thorough history and physical exam with all new patients.

The patient history should include questions regarding predisposing factors, duration, and rate of lesion growth, symptoms of tenderness, discharge, or bleeding, combined with careful clinical observation. A past medical history of skin cancer, UV exposure, and non-healing or recurrent cutaneous lesions should heighten suspicion of periorbital skin malignancy. Examination under magnification using a slit-lamp or dermoscopy is helpful in better characterization of any suspicious lesion. Notably, dermoscopy can reduce the need for unnecessary surgical procedures.[1][2]

When there is a suspicion of malignancy, a referral should be made for a biopsy and histopathological analysis. When indicated, treatment consists of surgical excision, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, cryosurgery, or laser treatments.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Actinic Keratosis (AK)

AK, or solar keratosis, typically arises from prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation. Other variables also influence their development, including male gender, older age, baldness, and history of melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma.[3]

Typically, lesions arise on the sun-exposed regions of the body—that is, the dorsum of the hands, shoulders, and face. They can occur alone or as multiple lesions and tend to have overlying yellow/brown scales. Adjacent skin may show signs of sun damage in the form of telangiectasias and yellow discoloration. Occasionally, heavily pigmented AKs may resemble lentigo maligna.[3]

Basal Cell Carcinoma (BCC)

Basal cell carcinoma is the most common skin malignancy in the world, with approximately 80% of lesions occurring in the head/neck region with 20% on the eyelids.[4] In one study, two-thirds of SCCs and one-third of BCCs were shown to arise from previously clinically diagnosed AKs in a high-risk population.[5]

For a more in-depth discussion on cutaneous BCC, the authors refer you to the StatPearls article dedicated to this; we will primarily focus on aspects specific to eyelid BCC.

Systemic conditions that may predispose a patient to BCC include:

- Sturge Weber/Port-wine stain

- Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome

- Gorlin-Goltz syndrome

- Rombo syndrome

- Bazex-Dupré-Christol syndrome

- Xeroderma pigmentosum

Squamous Cell Carcinoma (SCC) and Keratoacanthoma (KA)

Eyelid SCC is characterized by abnormal proliferation of cutaneous squamous cells. SCC typically arises from prolonged exposure to ultraviolet (UV) radiation and aging. Other causes include arsenic exposure, HPV infection, and HIV infection. Keratoacanthomas can be considered a well-differentiated variant of SCC, while actinic keratoses are defined as precancerous squamous lesions. As mentioned previously, one study showed that two-thirds of SCCs and one-third of BCCs arose from prior clinically diagnosed AKs in a high-risk population.[5]

Systemic conditions that may predispose a patient to KA/SCC include:

- Oculocutaneous albinism

- Epidermolysis bullosa

- Fanconi anemia

- Ferguson-Smith

- Muir-Torre syndrome

- Mibelli-type porokeratosis

- Rothmund-Thomson syndrome

- Keratitis-ichthyosis-deafness syndrome

- Bloom syndrome

- Epidermodysplasia verruciformis

- Xeroderma pigmentosum

Sebaceous Carcinoma (SC)

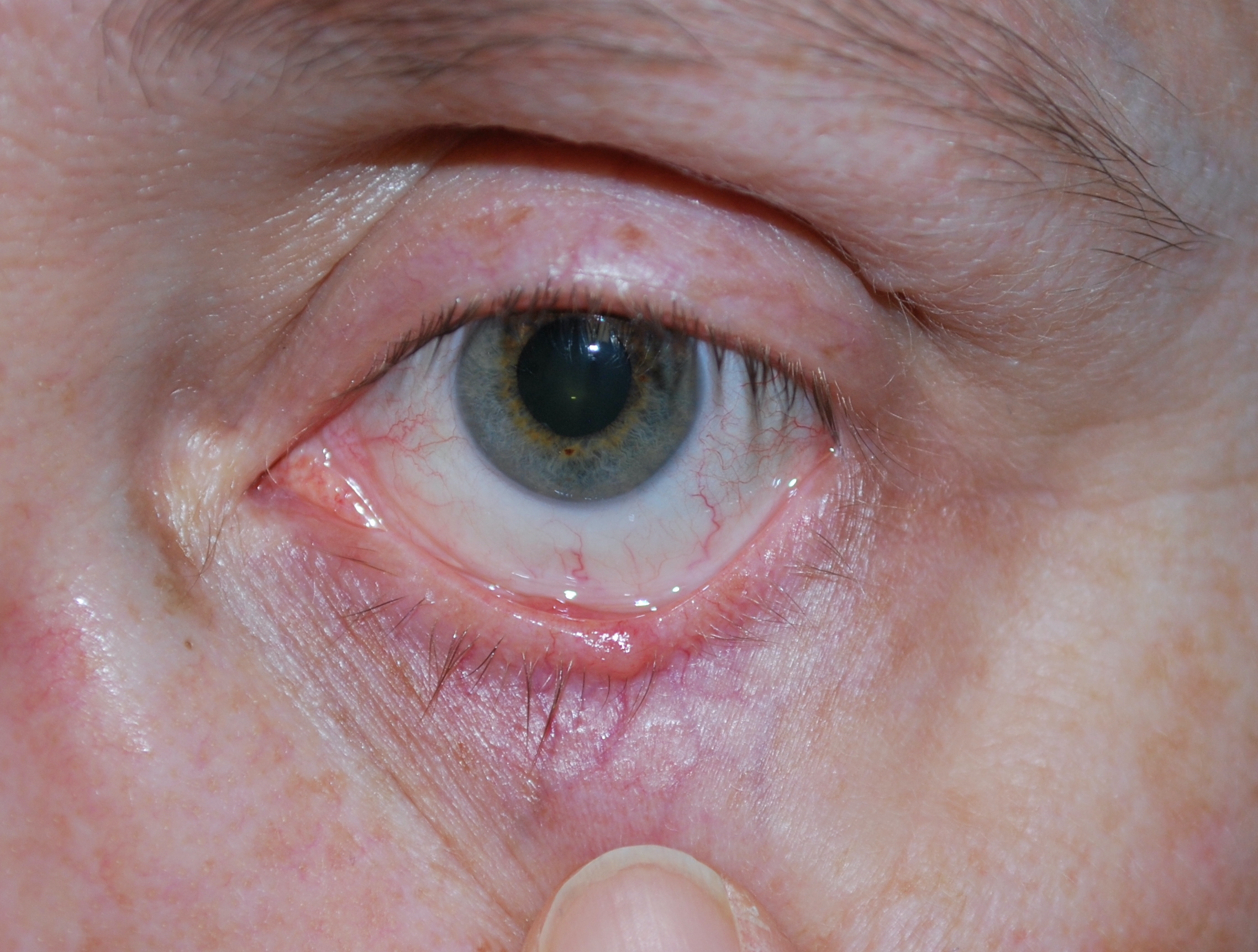

Sebaceous carcinoma (SC) of the eyelid typically presents as a yellow painless mass along the eyelid margin originating from sebaceous glands such as meibomian glands or glands of Zeis.[6] Its clinical appearance may resemble a chalazion or hordeolum, but the clinical history may differ. Additionally, given the origin of SC, these lesions may be located on the eyelid margin, caruncle, or the tarsal conjunctiva, demonstrating the importance of double-eversion of the upper lid during the ophthalmic exam.[7][8]

Melanoma

Eyelid melanoma can be thought of similarly to cutaneous melanoma. Excessive sun exposure, presence of dysplastic nevi, a personal history of melanoma, older age, and Fitzpatrick skin types I-II are all risk factors.[9][10][11]

Systemic conditions that may predispose a patient to this include

- Familial atypical multiple mole melanoma syndrome

- Familial melanoma

- Xeroderma pigmentosum

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC)

Merkel cells are mechanoreceptors and were historically thought to be the source of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). However, MCC is now known to have both an epithelial and neuroendocrine origin; for this reason, epidermal stem cells, dermal stem cells, and B-cells have also been suggested as alternative cells of origin.[12][13] Additionally, polyomaviruses have also been associated with the development of MCC.[14]

Epidemiology

In one large study of excised eyelid lesions, 59% were epidermal in origin, 1.5% were malignant, and 6% were premalignant (e.g., actinic keratosis or Bowen's disease). Of the malignant lesions, the majority (95%) were basal cell carcinoma, a minority (5%) squamous cell, and none were sebaceous cell carcinoma.[15]

In another large study of eyelid tumors, 85.7% were benign, 1.1% premalignant, and 13.1% malignant lesions. Of the malignant lesions, 60% originated from epidermal cells and 34.6% from adnexal cells. 56.5% of malignant tumors were basal cell carcinomas, 34.6% were sebaceous carcinoma, 3.8% were squamous cell carcinomas, and 1.7% were lymphoma or plasmacytoma.[16][17]

Actinic Keratosis

From 1990 to 1994, data from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey showed that 14% of all dermatology visits were for AK.[18] In the United States, the prevalence of AK in 2004 was about 40 million people.[19]

Prevalence rates vary by country and range from 23% in the South Wales Skin Cancer Study to 60% in patients from Australia.[20][21]

Risk factors for AK include male gender, significant cumulative sun exposure, older age, baldness, a personal history of melanoma or squamous cell carcinoma, and Fitzpatrick skin types I and II.[20][22]

Basal Cell Carcinoma

In the United States and Western countries, basal cell carcinoma is the most common malignancy of the eyelid. A recent study of the American Academy of Ophthalmology's IRIS registry showed BCC prevalence at 0.088%. Using data from the English Cancer Registries, Saleh et al. reported that the incidence of BCC in England was 0.0045%.[23]

As indicated above, there are regional variations, though basal cell carcinoma remains among the top two eyelid malignancies in all studied countries. For example, in India, BCC is the second most common eyelid malignancy (24%) after sebaceous carcinoma (53%).[24]

Squamous Cell Carcinoma & Keratoacanthoma

In the United States and Western countries, squamous cell carcinoma is the second most common malignancy of the eyelid after basal cell carcinoma, representing <5% of all eyelid malignancies. A recent study of the American Academy of Ophthalmology's IRIS registry showed prevalence at 0.011%. However, it is still 40 times less common than basal cell carcinoma. It typically occurs in patients over the age of 50, though it can present at any age.

In other countries, squamous cell carcinoma remains among the top three eyelid malignancies, though prevalence varies from region to region. For example, in India, SCC is the third most common eyelid malignancy (18%) after sebaceous carcinoma (53%) and basal cell carcinoma (24%).[24]

In addition, SCC occurs commonly after organ transplantation, with a reported incidence of 30% for lung transplants and 26% for heart transplant patients over five years. The prevalence of SCC amongst this group is related to post-transplantation systemic immunosuppression, which decreases the ability of the immune system to identify and destroy cancerous cells.[25][26]

Sebaceous Carcinoma

A meta-analysis of 1,333 patients demonstrated the mean age of patients diagnosed with SC is 65.2 years old, with 60.2% female predominance.[27] Other studies have shown a female prevalence ranging from 55.23% to 73%.[28][29] The upper eyelid is affected in 59% to 62.6% of cases; this is more common than the lower eyelid, which is involved in 32.8% in 41% of cases.[27]

Melanoma

Based on the National Cancer Database, a review of patients with head and neck melanoma from 2004 to 2015 reported that approximately 2% of cases affected the eyelids, with a higher prevalence in females (48%) than males (28.4%).[30] The lower eyelid is the most involved periorbital site, followed by the upper eyelid, eyebrow region, lateral canthus, and medial canthus.[31]

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC)

Eyelid-specific MCC rates are not well delineated. However, approximately 1500 cases of MCC are diagnosed each year.[32] Data from the National Cancer Institute from 1973 to 2006 shows that MCC predominately affects white patients (94.9%) between the ages of 60 and 85. 71.6% of patients were older than 70 at the time of diagnosis.[33]

Patients diagnosed at a younger age are typically immunosuppressed in the setting of HIV/AIDS or organ transplantation.[12] Between 45 to 48% of MCC arise in the head and neck region, and within this region, up to 20% of these cases originate on the eyelid.[34][35][36]

Lentigo Maligna

Lentigo maligna (LM) exists on the spectrum of melanoma. When invasive, this entity is referred to as lentigo maligna melanoma (LMM).[37] In this manner, LM can be categorized as melanoma in situ.[38][39] LMM accounts for 10% to 26% of melanomas in the head and neck region.

The chief concern for this lesion is the transformation from LM to LMM, which can occur in 5% to 50% of cases.[40][41] A study from Australia found that the average amount of time for conversion from LM to LMM was 28.3 years.[42]

Surgical excision is the primary treatment for these lesions, but for patients who are poor surgical candidates, topical agents (imiquimod cream, azelaic acid, 5-fluorouracil), cryotherapy, and radiotherapy are alternative treatment modalities.[43][44][45] For a more in-depth discussion on the topic, the authors refer you to the StatPearls article dedicated to this topic.[46]

There is a paucity of data regarding LM and LMM in the periocular region. For this reason, patients should be managed using a multidisciplinary approach consisting of oculoplastic surgeons, dermatologists, and primary care physicians.

Pathophysiology

Actinic Keratosis

UV-A and UV-B have been implicated in the molecular damage that leads to the development of AK, BCC, and SCC. Mutations of the p53 gene influenced by UV radiation have been seen in AKs. UV-A light can create reactive oxygen species that damage cellular structures, and UV-B light can cause thymidine-dimer creation, resulting in DNA damage.[47][48]

The proposed mechanisms behind this UV-induced DNA damage have led some to refer to AK as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in situ. Additionally, immunosuppression has also led to the development of AKs.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

UV radiation and smoking have been implicated as the major risk factor for developing BCC due to DNA damage.[49] Several studies have identified mutations in the PTCH1 gene (of the sonic hedgehog pathway) and p53 tumor suppressor gene in patients with BCC. The p53 tumor suppressor gene is critical to cell apoptosis and the prevention of tumorigenesis; a mutation in this gene leads to the uncontrolled growth of malignant cells.[50][51]

Squamous Cell Carcinoma & Keratoacanthoma

SCC falls on a spectrum of disorders ranging from precursors (e.g., actinic keratosis) to SCC. As in BCC, UV radiation is implicated as the major risk factor for developing SCC through DNA damage to the p53 tumor suppressor gene.[49] SCC can also commonly occur after organ transplantation, with a reported incidence of 30% for lung transplants and 26% for heart transplant patients over five years.[25][26] This finding is most likely related to the post-transplant immunosuppressants, which decrease the ability of the immune system to identify and destroy cancerous cells.

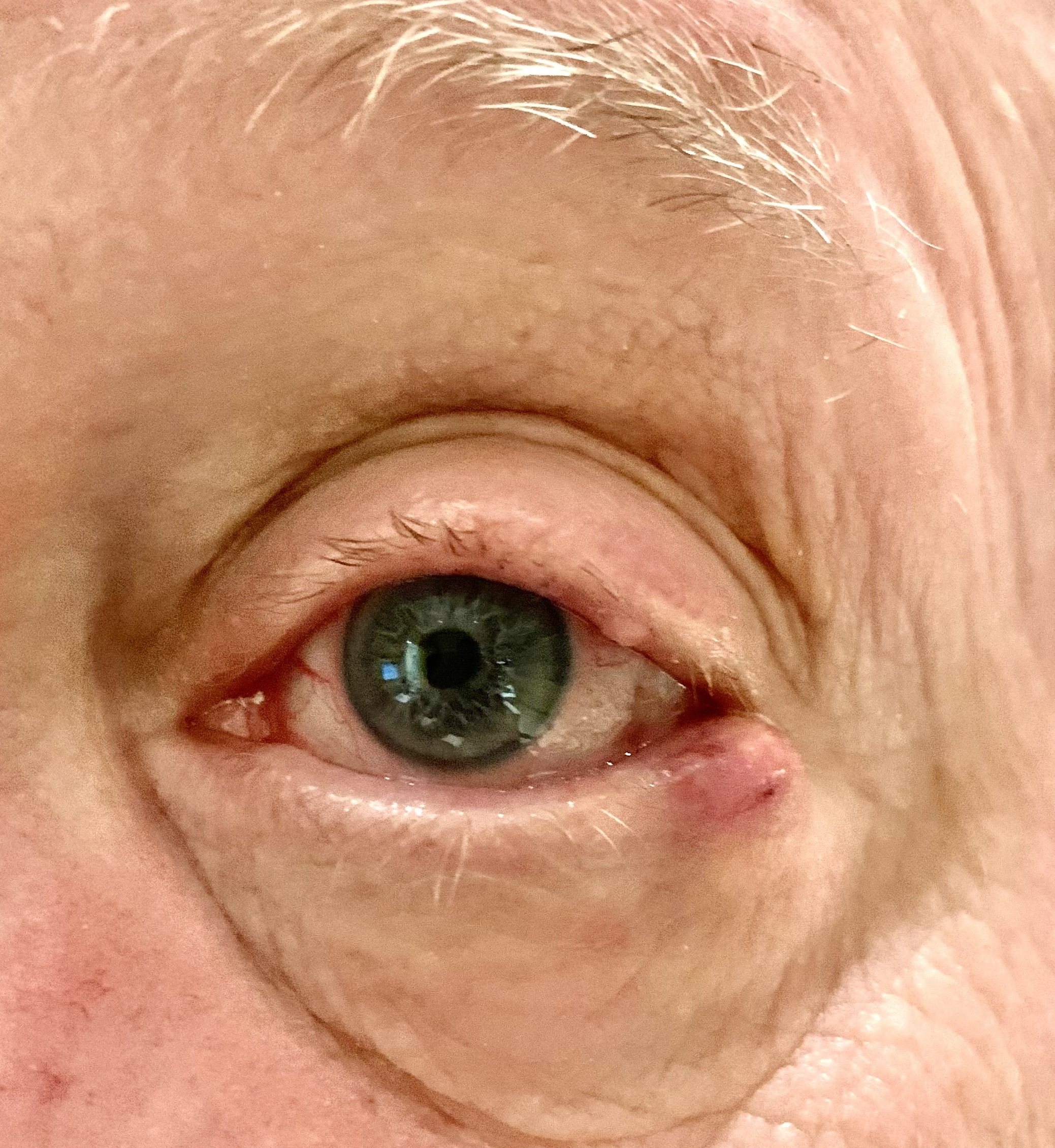

Keratoacanthoma often presents as a dome-shaped lesion with central hyperkeratosis and ulceration. Clinically, it is characterized by rapid growth followed by spontaneous involution. However, there are no pathognomonic characteristics that differentiate SCC and KAs.

Sebaceous Carcinoma

Although the exact pathogenesis of SC is unknown, multiple associations have been documented in the literature. Muir-Torre syndrome (MTS) is an autosomal dominant disorder with cutaneous malignancies such as SC and internal systemic malignancies such as colorectal and endometrial carcinoma.[52] MTS is more commonly associated with SC located outside of the periocular region.[53][54][55] Tumor locations, history of immunosuppression, history of radiotherapy, perineural involvement, and pathologic features should all be considered in risk stratification.[56][57][58][59]

Mutations in the TP53 gene have also been implicated in the development of periocular SC. A review of 15 patients with SC of the eyelid demonstrated that 66.7% contained point mutations in the p53 gene.[60] In Li-Fraumeni syndrome, a germline mutation in TP53 is associated with the development of SC.[61]

The high gene mutation rate of p53 might aid in obtaining an immunohistochemical (IHC) diagnosis of SC. Alterations in the expression of ERBB2, adhesion proteins (i.e., E-cadherin), and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition markers have also been demonstrated.[62]

Melanoma

The pathophysiology for melanoma is multifaceted, and knowledge of the various responsible mutations continues to grow. UV signatures are one of the most well-documented features of melanoma. These are defined as C-to-T transitions at dipyrimidine sites.[31] In addition to these UV signatures, other mutations must exist for transformation to melanoma. These include activating mutations (BRAF), tertiary mutations, invasive mutations, and immune system evasion mutations.[63][64]

50% of patients with advanced melanoma have BRAF mutations. The RAF isoforms are proteins involved with the activation of downstream pathways; the BRAF mutation leads to an 800-fold increase in kinase activity, leading to increased cellular proliferation.[65] Given the body of research that exists regarding the molecular pathophysiology of melanoma, further discussion is reserved for a dedicated article.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

MCC is poorly understood and multifarious. As previously mentioned, the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCPyV) has been implicated in developing MCC. Approximately 80% of MCC samples are associated with MCPyV. MCC can be further classified into virus-positive or virus-negative, as each demonstrates different characteristics and mutation-related changes. One of the more notable differences is that virus-positive cell lines exhibit a down-regulation of MHC-I proteins on the cell surface, inhibiting targeted tumor cell destruction.[66][67][68]

Immunosuppression is a well-documented and impressive risk factor for the development of cutaneous MCC; however, the associated incidence remains unclear. There is a demonstrated link between UV exposure and increased rates of MCC in sun-exposed skin. Additionally, using psoralens and the associated UV-A light has shown an increased incidence of MCC.[69]

Histopathology

Actinic Keratosis

Actinic keratosis demonstrates hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis within the epidermal layer. Dyskeratosis is typically present, as shown by premature keratinization of cells at the level of the stratum granulosum and spinosum. The dermal layer exhibits solar elastosis and may have a mild inflammatory infiltrate comprised chiefly of lymphocytes and plasma cells.

There are a few subtypes, such as hypertrophic and atrophic. Cellular atypia is always present, though to varying degrees of severity. As such, histopathological evaluation of the entirety of the lesion to include superficial stromal layers is necessary to exclude the possibility of stromal invasion, which, if present, would indicate squamous cell carcinoma.

Special stains are not generally needed in the diagnosis of actinic keratosis. However, pigmented actinic keratosis may mimic early melanoma, in which case special immunohistochemical stains may be used to help an experienced pathologist reach the correct diagnosis.

Melan-A staining may be positive in pigmented lesions. More recent studies suggest a role for HMB-45 in helping differentiate these pigmented lesions.[70][71] It also stains positively for cytokeratin.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Histologically, these lesions originate from the stratum basale of the epidermis. These cells are classically blue and basaloid in appearance and are located below the superficial skin, within the stromal layers. They have large, bland, crowded nuclei with a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio.

There are multiple histologic patterns, but all generally form dense islands of tumor cells with classic "palisading" at the edges of these tumor islands. These islands are separated from other dermal components by a clear margin as a result of refraction artifacts from tissue processing ("separation artifacts" or "clefts"). Within the islands, tumor cells show enlarged crowded nuclei and mitotic figures. Rapidly progressive BCC may demonstrate areas of necrosis.

As BCC is an epithelial tumor, it stains positively with cytokeratin. BerEp4 (stain for EpCAM antigen) is commonly used to assist in diagnosis, and it has high sensitivity and specificity for BCC but is negative in normal squamous epithelium.[72] However, it has limits in that it cannot distinguish BCC from Merkel cell carcinoma, basaloid squamous cell carcinoma, or trichoepithelioma because all are epithelial neoplasms of follicular germinative (trichoblastic) cell differentiation. Thus, other immunohistochemical stains are helpful for further characterization in these instances.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma & Keratoacanthoma

SCC tumor cells originate from the superficial epidermis. SCC tends to form nests and strands which extend into the dermis. The tumor cells are generally large with prominent eosinophilic cytoplasm and a high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio. Keratin pearls are often present.

SCC is typically classified based on the severity of characteristics of abnormal squamous epithelium. The degree of keratinization, presence of intercellular bridges (desmosomes), pleomorphism, and presence of mitotic figures are helpful in the stratification of SCC. They can be classified as well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, poorly differentiated, or undifferentiated. Perineural or lymphatic invasion may be present, the former presenting with pain.

As SCC is an epithelial tumor, it may be stained with cytokeratin. Poorly differentiated and undifferentiated forms may be difficult to establish and often requires additional immunohistochemical stains, such as desmin, to exclude melanoma or sarcoma.

Keratoacanthoma is often considered a well-differentiated form of SCC. As such, the histologic appearance is similar to that of SCC. It appears as a crater-like depression filled with keratin. It can be differentiated by the general well-differentiated nature of the squamous cells. Depending on the stage of growth or regression, it is often surrounded by a chronic inflammatory response. As a result of its many similarities to SCC, making the two difficult to differentiate, and the potential for malignant transformation, many ophthalmologists recommend complete excision of the lesion.

Sebaceous Carcinoma

Sebaceous carcinoma is of adnexal sebaceous origin, and histopathologic classification is based on the level of differentiation of the cells in the tumor. A well-differentiated tumor contains cells with sebaceous differentiation and "foamy" vacuolated cytoplasm. A moderately differentiated tumor histopathologically demonstrates most cells with hyperchromatic nuclei containing prominent nucleoli and basophilic cytoplasm with areas of well-differentiated sebaceous cells interspaced within.

A poorly differentiated tumor contains hyperchromatic, atypical cells with high mitotic activity. The comedocarcinoma subtype of SC often displays necrosis of the center of the tumor. Staining lipids with Oil Red O or human milk fat globulin-1 can help distinguish SC from squamous and basal cell carcinoma.[73]

SC can have flat (pagetoid) spread to the epidermis of the eyelid and epithelium of the conjunctiva and spread directly to the orbit, intracranial cavity, and paranasal sinuses. Poorly differentiated SGC can have perineural and lymphatic spread and metastatic spread to distant organs.

Melanoma

Malignant melanoma is of epidermal melanocytic origin and can originate from lentigo maligna or an intradermal melanocytic lesion such as a dysplastic nevus. In the case of the lentigo maligna, atypical melanocytes are present in the basal layers of the epidermis and the adnexal structures such as the eyelash pilar units. Regardless of its origin, a diagnosis of malignant melanoma is made when these atypical melanocytes are observed beyond the epidermal basement membrane.

Clark's and Breslow micro staging of skin melanoma is a method that strictly looks at the tumor's depth. Since the eyelid skin has a different structure, this type of staging is not applied. Eyelid margin involvement, depth of invasion, and the presence of skin ulceration are used as prognostic indicators. It is of note that ulceration is seldom seen in cutaneous eyelid melanoma. Other prognostic indicators, such as involvement of regional lymph nodes and the presence of distant metastases, have been reported, but the significance is uncertain due to the rare nature of eyelid melanoma.

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

Merkel cells are neuroendocrine receptor cells present in the mucous membrane and skin. Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare neurogenic tumor found in the upper eyelid and eyebrow, containing ample mitotic figures and round cells with round to oval nuclei with prominent nucleoli and reduced cytoplasm. Immunohistochemical staining positive for neuron-specific enolase, neurofilaments, and cytokeratin-20 and negative for S-100 and leukocyte-common antigen can differentiate MCC from other epithelial and neuroendocrine tumors.[34]

History and Physical

Every medical examination begins with history. The medical history should include a personal history of cutaneous or systemic cancer, immunosuppression, fair skin, radiation therapy, a family history of cancer, history of excessive sunlight exposure, and the presence of any non-healing or recurrent cutaneous lesions.

Patients should be asked about any eyelid lesion with symptoms of itching, bleeding, ulceration, blistering, chronicity, change in color, change in size, and loss of typical eyelid architecture (e.g., loss of eyelashes).

Examiners should ask about the location, onset, character, and time course of eyelid lesions, as well as any prior treatments or previous occurrence of the lesions. Perform eyelid and adnexal exams in ambiently-lit rooms with an additional dermatoscope, slit lamp, or pocket flashlight. Note the Fitzpatrick skin type of the patient and ascertain whether there is a significant difference in skin tone between sun-exposed and sun-protected areas.

Clinicians should assess for lesions with irregular pigmentation, ulceration with crusting or bleeding, telangiectatic vessels, or loss of eyelashes or cutaneous rhytids.

Examination under magnification using a slit-lamp or dermatoscope is helpful for better characterization of the lesion. Measure each suspicious lesion in millimeters in vertical and horizontal dimensions. Palpate the edges of the lesion to assess for involvement or fixation to deeper tissues.

Eversion of the lower lid and double-eversion of the upper lid is vital to ascertain the involvement of the conjunctival and fornices. Assess the preauricular, postauricular, submandibular, and submental lymph nodes for lymphadenopathy. Photograph the lesion to document its appearance.

If the patient has any suspicious eyelid lesion, referral to a dermatologist is warranted to ensure a full-body dermatologic examination. The presence of one skin cancer often portends the presence of another pre-cancerous or cancerous lesions elsewhere.

Evaluation

The clinician should assess the rate of progression, the timeline of development, and the presence of pain with eyelid lesions is essential when evaluating the potential for malignancy. The patient's best-corrected visual acuity, color vision, extraocular motility, pupillary responses, and visual field should also be measured.

These exam findings are often affected by the pathology of the globe, orbit, ocular adnexa, and periorbital tissue. More specifically, the following should be noted during the evaluation of a potentially malignant eyelid lesion:

- Color of the lesion(s)

- Size, measured in millimeters with vertical and horizontal dimensions and depth as applicable

- The appearance of telangiectasic or atypical vasculature

- Distortion of eyelid architecture

- For lesions involving the palpebral conjunctiva - recommend double-eversion of the upper eyelid to evaluate the conjunctival fornix

- Madarosis

- Ulceration

- Poliosis

- Local lymph node enlargement

Working closely with a pathologist to prepare an ideal specimen is imperative for an accurate and timely diagnosis. A full-thickness biopsy of the lesion for histopathologic evaluation should be obtained before initiating therapy for malignant lesions. In addition, potential metastasis should be considered as eyelid malignancies may represent only part of a more extensive malignant process or metastatic disease.

Orbital imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides details of orbital and periorbital soft tissue, and computerized tomography allows for assessing bony structures. Both of these imaging studies are useful for planning treatment.

Treatment / Management

Actinic Keratosis

Clear guidelines for managing AK do not exist given their propensity for spontaneous resolution; however, given the risk for malignant transformation, the clinician should not ignore these lesions. A review of practice patterns in 2012 regarding periocular AKs found that 60.2% of surveyed surgeons treat AKs <2mm with local excision and permanent pathology.[74]

Given the proximity of periorbital AKs to the globe, treatments such as cryotherapy, topical chemotherapy, photodynamic therapy, and laser therapy may present additional risks. They should be used on a case-by-case basis in conjunction with an ophthalmologist.

Basal Cell Carcinoma

The primary treatment modality for BCC of the eyelid remains surgical excision, typically Mohs micrographic surgery or local excision with 3 to 4 mm surgical margins. The resulting defect is then repaired by the Mohs surgeon or oculoplastic surgeon. If the extensive orbital invasion is identified, orbital exenteration has been performed in the past. More recent studies have shown the use of neoadjuvant vismodegib before surgical excision to avoid disfiguring orbital exenteration.[75][76](B3)

The SINS trial is a landmark study comparing excisional surgery and topical 5% imiquimod to treat BCC. Though the trial was not specific to eyelid tumors, it found that surgery was superior to imiquimod. While most imiquimod failures were limited to the first year of treatment, there were sustained benefits shown for other groups.[77][78][79] This suggests a possible role for imiquimod in selected cases of eyelid BCC.(A1)

Squamous Cell Carcinoma & Keratoacanthoma

Due to the difficulty in clinically differentiating SCC and KA, most physicians will opt for biopsy. If confirmed as KA, ophthalmologists may choose to either monitor or excise the lesion depending on size and location. In contrast, for non-eyelid KAs, excision is generally preferred due to a low risk for complications.

If SCC is confirmed on pathology, treatment is primarily surgical excision. This most commonly involves Mohs micrographic surgery with histopathologic clearance of surgical margins. The resulting defect is then repaired by the Mohs surgeon or an oculoplastic surgeon. If the SCC shows perineural invasion into the orbit, the patient should have further consideration of neoadjuvant treatment, globe-sparing or total orbital exenteration (depending on the extent of spread), and sentinel lymph node biopsy.

While surgical excision remains the standard of care for SCC, it is not always clinically possible; in such cases, radiation remains a viable option.[80] Additionally, SCC lesions have been shown to have elevated levels of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR). Thus, agents such as cetuximab, erlotinib, and gefitinib, which target and inhibit these EGFRs, have shown promise in SCC treatment, mainly to stabilize disease when surgical management is not possible.[81][82](B2)

Topical imiquimod, a topical immunomodulatory agent of the imidazoquinoline family, functions by activation of the innate and adaptive/acquired immune systems. In 2010, Ross et al. were the first to utilize imiquimod to treat moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid successfully.[83] More classically, imiquimod is associated with the treatment of basal cell carcinoma and precursor tumors, as shown in the landmark SINS trial.(B3)

Following successful surgical excision, patients should be counseled on proper sun protection, including sunscreen, UV-blocking sunglasses, wide-brimmed hats, long sleeve clothing, and other protective clothing, and to limit sun exposure, particularly in the middle of the day.

Sebaceous Carcinoma

Although there is no well-defined standard of care for the treatment and management of SC, the Committee on Invasive Skin Tumor Evidence-Based Recommendations (CISTERN) has recently published recommended guidelines for the management of SC.[56] It is important to note that the recommendations are different between extraocular and periocular SC. The CISTERN guidelines include:(A1)

- Biopsy of suspicious eyelid lesions does not require depth for diagnosis. Atypical chalazia or chronic unilateral blepharitis in patients >60 years old should raise concern.

- A complete cutaneous exam and adjacent lymph node exam should be performed. Ocular motility, proptosis, and pupillary abnormalities should be assessed.

- The 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for eyelid carcinoma may be used.

- Ultrasonography (US) or CT scans of the nodal basins may be used. Enlarged lymph nodes should be biopsied. Sentinel node biopsy can be considered for periocular sebaceous carcinoma. This differs from systemic cutaneous SC, where it is not recommended.

- Evaluation of distant metastasis with CT or PET scan should be used for confirmed nodal metastasis.

- Genetic testing for MTS with a Mayo Muir-Torre syndrome risk score of ≥ 2 is recommended.

- Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) or complete circumferential peripheral and deep margin assessment (CCPDMA) should be the primary management for periocular SC. Positive surgical margins may be treated with adjuvant double freeze-thaw cryotherapy or topical mitomycin.

- If MMS or CCPDMA is not feasible, staged wide local excision can be performed; however, this may increase morbidity.

- Extensive orbital involvement may be treated with orbital exenteration or radiotherapy as a monotherapy. However, the literature shows orbital exenteration appears to have improved mortality rates.

- Adjuvant radiotherapy may be considered in SC with perineural invasion.

- Surveillance every six months for the first three years after treatment is recommended before moving to annual follow-up. Periodic lymph node basin US may be considered.

Melanoma

Primary treatment of local malignancy consists of local, wide skin excision. Different extents of safety margins exist, typically based on the Breslow thickness of the melanoma. Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SNLB) may aid in managing patients with eyelid melanoma. One study found that 21.4% of patients with eyelid melanoma had positive SNLB.[84]

The most common locations of positive SNLB in the setting of ocular adnexal melanoma are the preauricular, intraparotid, and submandibular nodal basins.[85] SNLB provides important prognostic information, but guidelines on when to initiate this procedure have yet to be defined.

For patients presenting with metastatic disease, surgical excision is not curative. Dacarbazine, an imidazole carboxamide chemotherapeutic agent, has been the first drug therapy for metastatic melanoma since 2006.[86]

Biologic immunotherapies (e.g., interleukin-2 and interferons), vaccination strategies, and adoptive cell therapy are all immunotherapies that have been employed to combat metastatic malignant melanoma. Most notably, immune checkpoint inhibitors (i.e., ipilimumab, nivolumab, and pembrolizumab) are the newest and fastest-growing area of investigation in treating metastatic melanoma. Their discussion should be reserved for a separate article.[87][88](B3)

Merkel Cell Carcinoma (MCC)

Before treatment of MCC, staging of the tumor should be performed using the AJCC staging system. Given the aggressive nature of MCC and associated high mortality rate, sentinel lymph node biopsy (SNLB) should be considered. Surgical excision, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and immunotherapy have all been used to treat MCC. For surgical excision, wide excision with 5mm margins is recommended. Additionally, given the radiosensitivity of these tumors, adjuvant radiotherapy may be warranted.[89][90] (B2)

Chemotherapy is efficacious in treating MCC as a first-line treatment for disseminated or metastatic disease rather than as a local or adjuvant treatment.[91][92][93][94] Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab, nivolumab, and avelumab are currently being added to the treatment portfolio of MCC. Notably, avelumab has demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of eyelid-specific diseases.[95][96](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis has been organized based on tissue types of the eyelid tissue.

Epithelium

Pre-malignant Lesions

- Actinic or solar keratosis (pre-malignant)

- Seborrheic keratosis

- Keratoacanthoma

- Cutaneous horn

Malignant Lesions

- Carcinoma in situ - Bowen disease (stage 0, non-invasive malignancy)

- Basal cell carcinoma

- Nodular

- Noduloulcerative

- Pigmented

- Infiltrating

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Merkel cell carcinoma

Melanocytes

Pre-malignant Lesions

- Dysplastic nevus

- Large congenital nevi (over 20 cm in size) have an estimated 4 to 20% risk of malignant transformation.

- Blue nevus variants: Blue nevi in their pure histopathological form are benign. However, similar variants have transformation potential, as is the case in blue nevus-like melanoma.

- Oculodermal melanocytosis requires semi-annual monitoring for glaucoma and melanoma of the skin, iris, and choroid.

Malignant Lesions

- Melanoma

Adnexal Lesions

Hair follicles

- Malignant hair follicle tumor (a variant of BCC)

Sweat glands

- Malignant syringoma

- Mucinous sweat gland adenocarcinoma

- Gland of Moll adenosarcoma

Sebaceous glands

- Sebaceous carcinoma

Staging

The eyelid consists of four to seven layers of tissue, depending on the distance from the eyelid margin. Theoretically, each of these layers can give rise to malignant neoplasms. The upper and lower eyelid layers include:

- Skin, subcutaneous tissue, and adnexa (upper and lower lids)

- Orbicularis muscle (upper and lower lids)

- Orbital septum (upper and lower lid)

- Pre-aponeurotic orbital fat (upper lid, superior to tarsus)

- Pre-capsulopalpebral fascial fat (lower lid, inferior to tarsus)

- Levator aponeurosis (upper lid)

- Capsulopalpebral fascia (lower lid)

- Müller muscle (upper lid)

- Tarsus with the meibomian glands (upper and lower lids)

- Palpebral conjunctiva (upper and lower lids)

Adnexal structures in the eyelid skin include eyelashes, sebaceous glands of Zeis, and sweat glands of Moll. The levator and orbicularis muscles are composed of striated muscle, while Müller's muscle is composed of smooth muscle.

The marginal aspect of the orbicularis muscle is called the muscle of Riolan; the superficial part of this muscle is visible as a colored line that separates the meibomian gland orifices from the row of eyelashes. This line is called the gray line and is significant as it demarcates the position of the eyelid septum. Lesions in front of the septum are called preseptal. Most malignant eyelid lesions are preseptal as they originate in the skin.

Knowledge of the anatomy above aids in staging these lesions according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) Tumor-Nodes-Metastasis (TNM) Classification System.[97] The AJCC has a standardized staging system that applies explicitly to the eyelid (Table 1).

In 2021, the largest analysis of cutaneous melanoma of the eyelid was published. In this study, the 5-year overall survival rate was 88.6% for melanoma in situ and 77.1% for invasive melanoma. Additionally, the authors found that age ≥75 years at diagnosis, T4 staging, lymph node involvement, and the nodular melanoma histologic subtype portended poor survival.[98]

Additional risk stratification and staging tools include:

- Fitzpatrick skin type

- 8th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system

- Clark level of invasion (see section Prognosis: Melanoma)

- Breslow tumor thickness (see section Prognosis: Melanoma)

Table 1

| TYPE PRIMARY TUMOR (T) | DEFINITIONS |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| Tis | Carcinoma in situ |

| T1 | Tumor ≤ 5 mm, but not >10 mm, in greatestdimension or any tumor that invades thetarsal plate or eyelid margin |

| T2b | Tumor > 10 mm, but not 20 mm, in greatestdimension, or involves full-thickness eyelid |

| T3a | Tumor > 20 mm in greatest dimension, or anytumor that invades adjacent ocular or orbitalstructures. Any T with perineural invasion |

| T3b | Complete tumor resection requires enucleation, exenteration, or bone resection |

| T4 |

The tumor is not resectable because of extensive invasion of ocular, orbital, or craniofacial structures or brain |

| REGIONAL LYMPH NODES (N) | |

| NX | Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed |

|

cN0 |

No regional lymph node metastasis, based on clinical evaluation or imaging |

|

pN0 |

No regional lymph node metastasis, based on lymph node biopsy |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| DISTANT METASTASIS | |

| M0 | No distant metastasis |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

Prognosis

Prognosis is variable and is dependent upon the histopathologic classification and staging of the tumor.

Actinic Keratosis

Although AK does not infer any impact on survival, the risk of transforming into a malignant entity is the most significant concern, given that it is a benign lesion. Signs of progression from an AK to malignancy include ulceration, rapid growth, size >1cm, and inflammation.[99] Between 21 and 70% of AKs show spontaneous regression. However, their presence has been shown to incur a six times greater risk for skin cancer.[100]

Basal Cell Carcinoma

Fifty percent of BCC lesions are found on the lower lid, 30% medial canthus, 15% upper lid, and 5% lateral canthus.[101] Prognosis is generally excellent, with a successful cure rate of 95% and a recurrence rate of 1 to 5% per year following surgical excision. However, patients with BCC associated with basal cell nevus syndrome (i.e., Gorlin syndrome) have a lifelong risk of multiple BCCs.

Squamous Cell Carcinoma & Keratoacanthoma

Like in BCC, lesions of the lower lid account for the majority of SCC cases (60.8%), followed by lesions of the medial canthus (17.6%) and lateral canthus (11.8%), and upper lid (9.8%). SCC is typically more aggressive than BCC. The overall mortality prognosis is good as long as clear margins can be obtained, though significant morbidity remains. A 2002 study revealed only one death out of 51 patients with a mean follow-up of 31 months, with the only death occurring in a patient who declined treatment.[102]

Sebaceous Carcinoma

Misdiagnosis plays an integral role in the poor prognosis associated with SC. In one study of patients with SC, nearly 60% of patients had an average diagnostic delay of 14.7 months. Chalazion and blepharitis represent the most common incorrect diagnosis for sebaceous carcinoma at 15.9 to 20% and 14.4 to 25%, respectively.[27][28] This high likelihood of misdiagnosis leads to its poor prognosis and a mortality rate that was once as high as 50%.[103][104] A trend toward improved prognosis has been shown, with mortality ranging from 4 to 11%.[104][105][106][107]

Melanoma

One retrospective review of 256 patients found that lesions involving the eyelids or caruncle had more than a twofold increase in mortality relative to malignant melanoma of the globe.[108] The Clark level was the first proposed grading system for melanoma and considered which anatomic compartment the tumor involved (i.e., epidermis, papillary dermis, reticular dermis, and subcutaneous fat); the limitation of the Clark system was the variation of compartment thickness throughout the body.[86] In the 1970s, the Breslow staging system was created and considered the depth of invasion by millimeters (mm) rather than the anatomical compartment.

The most commonly used staging system, the TNM (tumor, node, metastasis), was introduced by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). In 2021, the largest analysis of cutaneous melanoma of the eyelid was published, showing the 5-year overall survival rate was 88.6% for melanoma in situ and 77.1% for invasive melanoma. Additionally, the authors found that age ≥75 years at diagnosis, T4 staging, lymph node involvement, and the nodular melanoma histologic subtype are harbingers of poor survival.[98]

Merkel Cell Carcinoma

A diagnosis of MCC imparts a poor prognosis with a mortality ranging from 33% to 46%.[109] This is attributed to delay of diagnosis, aggressive growth, nodal and distant metastases, and high incidence of local recurrence. Poor predictive prognostic factors include male sex, immunosuppression, tumor size between 2 cm and 5 cm, nodal metastasis, and older age. Between 10% to 30% of eyelid MCCs metastasize to distant sites, including lymph nodes, bone, brain, liver, and lung.[89][110]

Complications

Misdiagnosis results in prolonged observation which may result in more extensive local growth of the lesion. Perineural, hematogenous, or lymphatic spread may also develop the following misdiagnosis. Iatrogenic complications from periocular surgery and radiotherapy carry a number of risks.[111] These include:

- Lagophthalmos

- Symblepharon

- Eyelid retraction

- Ptosis

- Ectropion

- Entropion

- Trichiasis

- Dry eye syndrome from exposure, aqueous deficiency, or evaporation

- Damage to the nasolacrimal system

- Diplopia

- Globe injury & damage to surrounding structures

- Orbital hemorrhage

- Infection

- Poor tissue healing (primarily with radiotherapy)

- Poor cosmetic outcome

- Psychologic distress

Each immunologic and chemotherapeutic agent carries specific complications, and physicians should work closely with oncologists and pharmacists when considering treatment options.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education should occur at each visit to mitigate the risk of developing eyelid malignancy. The two most important modifiable risk factors are sun protection and nicotine avoidance or cessation. Patients should avoid ultraviolet radiation; short-wavelength UVB radiation is more damaging than long-wavelength UVA radiation and can induce DNA damage in tumor-suppression genes. Studies suggest that UV exposure contributes to almost 65% of melanoma and 90% of nonmelanoma skin cancer.[112]

Educate patients to avoid excess sun exposure, wear wide-brim hats to shade the head and neck, avoid tanning salons, and apply SPF lotion. In addition, clinicians should counsel patients against nicotine use as this has increased the risk of malignancies. Furthermore, patients with a family history of skin cancers, immunosuppressive status, previous radiation, or exposure to toxic substances are at higher risk of developing skin malignancies.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

With age-related changes in the skin, malignant eyelid lesions may go unrecognized.[113][114][115]

The incidence of all cutaneous malignancy is increasing worldwide and varies with geography and race. Patients with Fitzpatrick skin types I-III are generally more susceptible to sunburns, which can increase the chance of skin cancer. Early diagnosis and treatment remain the gold standard to improve the overall outcome and better cosmesis. For example, approximately 40% of patients who have had one BCC will develop another lesion within five years.[116]

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) remains the most common periorbital skin cancer, followed by squamous cell, melanoma, and sebaceous carcinoma. Basal and squamous cell carcinomas most commonly occur in the lower lid and medial canthus. In contrast, sebaceous carcinoma occurs more commonly in the upper eyelid due to the preponderance of Meibomian glands.

Melanoma can occur in any location around the eye, including the lids, conjunctiva, cornea, uvea, and orbit. Any periorbital skin malignancy, if neglected, can invade the orbit, resulting in significant morbidity to achieve control of the disease. The rate of orbital invasion is 2 to 4% in BCC, with risk factors including large tumor size, multiple recurrences, infiltrative histological subtype, perineural spread, medial or lateral canthus localization, and increased age.

Education on UV avoidance, access to skin and ophthalmic examinations, and public education on the appearance and treatment of abnormal skin lesions are critical to diagnosing and curing periorbital cutaneous malignancies. Therefore, an interprofessional team approach to managing these lesions with all members communicating openly about the patient's condition and sharing in the patient education duties will yield the best outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tromme I, Sacré L, Hammouch F, Legrand C, Marot L, Vereecken P, Theate I, van Eeckhout P, Richez P, Baurain JF, Thomas L, Speybroeck N, DEPIMELA study group. Availability of digital dermoscopy in daily practice dramatically reduces the number of excised melanocytic lesions: results from an observational study. The British journal of dermatology. 2012 Oct:167(4):778-86. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11042.x. Epub 2012 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 22564185]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHaenssle HA, Krueger U, Vente C, Thoms KM, Bertsch HP, Zutt M, Rosenberger A, Neumann C, Emmert S. Results from an observational trial: digital epiluminescence microscopy follow-up of atypical nevi increases the sensitivity and the chance of success of conventional dermoscopy in detecting melanoma. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2006 May:126(5):980-5 [PubMed PMID: 16514414]

Rossi R, Mori M, Lotti T. Actinic keratosis. International journal of dermatology. 2007 Sep:46(9):895-904 [PubMed PMID: 17822489]

Shi Y, Jia R, Fan X. Ocular basal cell carcinoma: a brief literature review of clinical diagnosis and treatment. OncoTargets and therapy. 2017:10():2483-2489. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S130371. Epub 2017 May 8 [PubMed PMID: 28507440]

Criscione VD, Weinstock MA, Naylor MF, Luque C, Eide MJ, Bingham SF, Department of Veteran Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial Group. Actinic keratoses: Natural history and risk of malignant transformation in the Veterans Affairs Topical Tretinoin Chemoprevention Trial. Cancer. 2009 Jun 1:115(11):2523-30. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24284. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19382202]

Song A, Carter KD, Syed NA, Song J, Nerad JA. Sebaceous cell carcinoma of the ocular adnexa: clinical presentations, histopathology, and outcomes. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2008 May-Jun:24(3):194-200. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e31816d925f. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18520834]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKass LG, Hornblass A. Sebaceous carcinoma of the ocular adnexa. Survey of ophthalmology. 1989 May-Jun:33(6):477-90 [PubMed PMID: 2658172]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBest M, De Chabon A, Park J, Galin MA. Sebaceous carcinoma of glands of Zeis. New York state journal of medicine. 1970 Feb 1:70(3):433-5 [PubMed PMID: 5262246]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGandini S, Autier P, Boniol M. Reviews on sun exposure and artificial light and melanoma. Progress in biophysics and molecular biology. 2011 Dec:107(3):362-6. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2011.09.011. Epub 2011 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 21958910]

Berwick M, Erdei E, Hay J. Melanoma epidemiology and public health. Dermatologic clinics. 2009 Apr:27(2):205-14, viii. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2008.12.002. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19254665]

van der Leest RJ, Flohil SC, Arends LR, de Vries E, Nijsten T. Risk of subsequent cutaneous malignancy in patients with prior melanoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2015 Jun:29(6):1053-62. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12887. Epub 2014 Dec 10 [PubMed PMID: 25491923]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceNorth VS, Habib LA, Yoon MK. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid: A review. Survey of ophthalmology. 2019 Sep-Oct:64(5):659-667. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2019.03.002. Epub 2019 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 30871952]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmaral T, Leiter U, Garbe C. Merkel cell carcinoma: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis and therapy. Reviews in endocrine & metabolic disorders. 2017 Dec:18(4):517-532. doi: 10.1007/s11154-017-9433-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28916903]

Feng H, Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Clonal integration of a polyomavirus in human Merkel cell carcinoma. Science (New York, N.Y.). 2008 Feb 22:319(5866):1096-100. doi: 10.1126/science.1152586. Epub 2008 Jan 17 [PubMed PMID: 18202256]

Gundogan FC, Yolcu U, Tas A, Sahin OF, Uzun S, Cermik H, Ozaydin S, Ilhan A, Altun S, Ozturk M, Sahin F, Erdem U. Eyelid tumors: clinical data from an eye center in Ankara, Turkey. Asian Pacific journal of cancer prevention : APJCP. 2015:16(10):4265-9 [PubMed PMID: 26028084]

Yu SS, Zhao Y, Zhao H, Lin JY, Tang X. A retrospective study of 2228 cases with eyelid tumors. International journal of ophthalmology. 2018:11(11):1835-1841. doi: 10.18240/ijo.2018.11.16. Epub 2018 Nov 18 [PubMed PMID: 30450316]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceXu XL, Li B, Sun XL, Li LQ, Ren RJ, Gao F. [Clinical and pathological analysis of 2639 cases of eyelid tumors]. [Zhonghua yan ke za zhi] Chinese journal of ophthalmology. 2008 Jan:44(1):38-41 [PubMed PMID: 18510241]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGupta AK, Cooper EA, Feldman SR, Fleischer AB Jr. A survey of office visits for actinic keratosis as reported by NAMCS, 1990-1999. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cutis. 2002 Aug:70(2 Suppl):8-13 [PubMed PMID: 12353680]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBickers DR, Lim HW, Margolis D, Weinstock MA, Goodman C, Faulkner E, Gould C, Gemmen E, Dall T, American Academy of Dermatology Association, Society for Investigative Dermatology. The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2006 Sep:55(3):490-500 [PubMed PMID: 16908356]

Harvey I, Frankel S, Marks R, Shalom D, Nolan-Farrell M. Non-melanoma skin cancer and solar keratoses. I. Methods and descriptive results of the South Wales Skin Cancer Study. British journal of cancer. 1996 Oct:74(8):1302-7 [PubMed PMID: 8883422]

Marks R, Ponsford MW, Selwood TS, Goodman G, Mason G. Non-melanotic skin cancer and solar keratoses in Victoria. The Medical journal of Australia. 1983 Dec 10-24:2(12):619-22 [PubMed PMID: 6669125]

Flohil SC, van der Leest RJ, Dowlatshahi EA, Hofman A, de Vries E, Nijsten T. Prevalence of actinic keratosis and its risk factors in the general population: the Rotterdam Study. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2013 Aug:133(8):1971-8. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.134. Epub 2013 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 23510990]

Saleh GM, Desai P, Collin JR, Ives A, Jones T, Hussain B. Incidence of eyelid basal cell carcinoma in England: 2000-2010. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2017 Feb:101(2):209-212. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2015-308261. Epub 2016 Apr 29 [PubMed PMID: 27130914]

Kaliki S, Bothra N, Bejjanki KM, Nayak A, Ramappa G, Mohamed A, Dave TV, Ali MJ, Naik MN. Malignant Eyelid Tumors in India: A Study of 536 Asian Indian Patients. Ocular oncology and pathology. 2019 Apr:5(3):210-219. doi: 10.1159/000491549. Epub 2018 Sep 13 [PubMed PMID: 31049330]

Singer JP, Boker A, Metchnikoff C, Binstock M, Boettger R, Golden JA, Glidden DV, Arron ST. High cumulative dose exposure to voriconazole is associated with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in lung transplant recipients. The Journal of heart and lung transplantation : the official publication of the International Society for Heart Transplantation. 2012 Jul:31(7):694-9. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.02.033. Epub 2012 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 22484291]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlam M, Brown RN, Silber DH, Mullen GM, Feldman DS, Oren RM, Yancy CW, Cardiac Transplant Research Database Group. Increased incidence and mortality associated with skin cancers after cardiac transplant. American journal of transplantation : official journal of the American Society of Transplantation and the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. 2011 Jul:11(7):1488-97. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03598.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21718441]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDesiato VM, Byun YJ, Nguyen SA, Thiers BH, Day TA. Sebaceous Carcinoma of the Eyelid: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2021 Jan 1:47(1):104-110. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000002660. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33347004]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceShields JA, Demirci H, Marr BP, Eagle RC Jr, Shields CL. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelids: personal experience with 60 cases. Ophthalmology. 2004 Dec:111(12):2151-7 [PubMed PMID: 15582067]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKale SM, Patil SB, Khare N, Math M, Jain A, Jaiswal S. Clinicopathological analysis of eyelid malignancies - A review of 85 cases. Indian journal of plastic surgery : official publication of the Association of Plastic Surgeons of India. 2012 Jan:45(1):22-8. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.96572. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22754148]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOliver JD, Boczar D, Sisti A, Huayllani MT, Restrepo DJ, Spaulding AC, Gabriel E, Bagaria S, Rinker BD, Forte AJ. Eyelid Melanoma in the United States: A National Cancer Database Analysis. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2019 Nov-Dec:30(8):2412-2415. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005673. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31233000]

Mancera N, Smalley KSM, Margo CE. Melanoma of the eyelid and periocular skin: Histopathologic classification and molecular pathology. Survey of ophthalmology. 2019 May-Jun:64(3):272-288. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2018.12.002. Epub 2018 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 30578807]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLemos B, Nghiem P. Merkel cell carcinoma: more deaths but still no pathway to blame. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2007 Sep:127(9):2100-3 [PubMed PMID: 17700621]

Albores-Saavedra J, Batich K, Chable-Montero F, Sagy N, Schwartz AM, Henson DE. Merkel cell carcinoma demographics, morphology, and survival based on 3870 cases: a population based study. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2010 Jan:37(1):20-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01370.x. Epub 2009 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 19638070]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMerritt H, Sniegowski MC, Esmaeli B. Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid and periocular region. Cancers. 2014 May 9:6(2):1128-37. doi: 10.3390/cancers6021128. Epub 2014 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 24821131]

Lemos BD, Storer BE, Iyer JG, Phillips JL, Bichakjian CK, Fang LC, Johnson TM, Liegeois-Kwon NJ, Otley CC, Paulson KG, Ross MI, Yu SS, Zeitouni NC, Byrd DR, Sondak VK, Gershenwald JE, Sober AJ, Nghiem P. Pathologic nodal evaluation improves prognostic accuracy in Merkel cell carcinoma: analysis of 5823 cases as the basis of the first consensus staging system. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2010 Nov:63(5):751-61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.02.056. Epub 2010 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 20646783]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmith VA, Camp ER, Lentsch EJ. Merkel cell carcinoma: identification of prognostic factors unique to tumors located in the head and neck based on analysis of SEER data. The Laryngoscope. 2012 Jun:122(6):1283-90. doi: 10.1002/lary.23222. Epub 2012 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 22522673]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCohen LM. Lentigo maligna and lentigo maligna melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1995 Dec:33(6):923-36; quiz 937-40 [PubMed PMID: 7490362]

Dubow BE,Ackerman AB, Ideas in pathology. Malignant melanoma in situ: the evolution of a concept. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 1990 Nov; [PubMed PMID: 2263599]

DeWane ME, Kelsey A, Oliviero M, Rabinovitz H, Grant-Kels JM. Melanoma on chronically sun-damaged skin: Lentigo maligna and desmoplastic melanoma. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2019 Sep:81(3):823-833. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.066. Epub 2019 Mar 28 [PubMed PMID: 30930085]

McKenna JK, Florell SR, Goldman GD, Bowen GM. Lentigo maligna/lentigo maligna melanoma: current state of diagnosis and treatment. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2006 Apr:32(4):493-504 [PubMed PMID: 16681656]

Weinstock MA, Sober AJ. The risk of progression of lentigo maligna to lentigo maligna melanoma. The British journal of dermatology. 1987 Mar:116(3):303-10 [PubMed PMID: 3567069]

Menzies SW,Liyanarachchi S,Coates E,Smith A,Cooke-Yarborough C,Lo S,Armstrong B,Scolyer RA,Guitera P, Estimated risk of progression of lentigo maligna to lentigo maligna melanoma. Melanoma research. 2020 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 31095041]

Erickson C, Miller SJ. Treatment options in melanoma in situ: topical and radiation therapy, excision and Mohs surgery. International journal of dermatology. 2010 May:49(5):482-91. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2010.04423.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20534080]

McLeod M, Choudhary S, Giannakakis G, Nouri K. Surgical treatments for lentigo maligna: a review. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2011 Sep:37(9):1210-28. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02042.x. Epub 2011 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 21631635]

Marsden JR, Fox R, Boota NM, Cook M, Wheatley K, Billingham LJ, Steven NM, NCRI Skin Cancer Clinical Studies Group, the U.K. Dermatology Clinical Trials Network and the LIMIT-1 Collaborative Group. Effect of topical imiquimod as primary treatment for lentigo maligna: the LIMIT-1 study. The British journal of dermatology. 2017 May:176(5):1148-1154. doi: 10.1111/bjd.15112. Epub 2017 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 27714781]

Xiong M, Charifa A, Chen CSJ. Lentigo Maligna Melanoma. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489150]

Nelson MA, Einspahr JG, Alberts DS, Balfour CA, Wymer JA, Welch KL, Salasche SJ, Bangert JL, Grogan TM, Bozzo PO. Analysis of the p53 gene in human precancerous actinic keratosis lesions and squamous cell cancers. Cancer letters. 1994 Sep 30:85(1):23-9 [PubMed PMID: 7923098]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTaguchi M, Watanabe S, Yashima K, Murakami Y, Sekiya T, Ikeda S. Aberrations of the tumor suppressor p53 gene and p53 protein in solar keratosis in human skin. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 1994 Oct:103(4):500-3 [PubMed PMID: 7930674]

Rivlin N, Brosh R, Oren M, Rotter V. Mutations in the p53 Tumor Suppressor Gene: Important Milestones at the Various Steps of Tumorigenesis. Genes & cancer. 2011 Apr:2(4):466-74. doi: 10.1177/1947601911408889. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21779514]

Dahmane N, Lee J, Robins P, Heller P, Ruiz i Altaba A. Activation of the transcription factor Gli1 and the Sonic hedgehog signalling pathway in skin tumours. Nature. 1997 Oct 23:389(6653):876-81 [PubMed PMID: 9349822]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceYin VT, Merritt H, Esmaeli B. Targeting EGFR and sonic hedgehog pathways for locally advanced eyelid and periocular carcinomas. World journal of clinical cases. 2014 Sep 16:2(9):432-8. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v2.i9.432. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25232546]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee JB, Litzner BR, Vidal CI. Review of the current medical literature and assessment of current utilization patterns regarding mismatch repair protein immunohistochemistry in cutaneous Muir-Torre syndrome-associated neoplasms. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2017 Nov:44(11):931-937. doi: 10.1111/cup.13010. Epub 2017 Aug 29 [PubMed PMID: 28749576]

Dores GM, Curtis RE, Toro JR, Devesa SS, Fraumeni JF Jr. Incidence of cutaneous sebaceous carcinoma and risk of associated neoplasms: insight into Muir-Torre syndrome. Cancer. 2008 Dec 15:113(12):3372-81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23963. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18932259]

Eiger-Moscovich M, Eagle RC Jr, Shields CL, Racher H, Lally SE, Silkiss RZ, Shields JA, Milman T. Muir-Torre Syndrome Associated Periocular Sebaceous Neoplasms: Screening Patterns in the Literature and in Clinical Practice. Ocular oncology and pathology. 2020 Aug:6(4):226-237. doi: 10.1159/000504984. Epub 2020 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 33005611]

Kyllo RL, Brady KL, Hurst EA. Sebaceous carcinoma: review of the literature. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2015 Jan:41(1):1-15. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000000152. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25521100]

Owen JL,Kibbi N,Worley B,Kelm RC,Wang JV,Barker CA,Behshad R,Bichakjian CK,Bolotin D,Bordeaux JS,Bradshaw SH,Cartee TV,Chandra S,Cho NL,Choi JN,Council ML,Demirci H,Eisen DB,Esmaeli B,Golda N,Huang CC,Ibrahim SF,Jiang SB,Kim J,Kuzel TM,Lai SY,Lawrence N,Lee EH,Leitenberger JJ,Maher IA,Mann MW,Minkis K,Mittal BB,Nehal KS,Neuhaus IM,Ozog DM,Petersen B,Rotemberg V,Samant S,Samie FH,Servaes S,Shields CL,Shin TM,Sobanko JF,Somani AK,Stebbins WG,Thomas JR,Thomas VD,Tse DT,Waldman AH,Wong MK,Xu YG,Yu SS,Zeitouni NC,Ramsay T,Reynolds KA,Poon E,Alam M, Sebaceous carcinoma: evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. The Lancet. Oncology. 2019 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 31797796]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWick MR, Goellner JR, Wolfe JT 3rd, Su WP. Adnexal carcinomas of the skin. II. Extraocular sebaceous carcinomas. Cancer. 1985 Sep 1:56(5):1163-72 [PubMed PMID: 4016704]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLanoy E, Dores GM, Madeleine MM, Toro JR, Fraumeni JF Jr, Engels EA. Epidemiology of nonkeratinocytic skin cancers among persons with AIDS in the United States. AIDS (London, England). 2009 Jan 28:23(3):385-93. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283213046. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19114864]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLandis MN, Davis CL, Bellus GA, Wolverton SE. Immunosuppression and sebaceous tumors: a confirmed diagnosis of Muir-Torre syndrome unmasked by immunosuppressive therapy. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011 Nov:65(5):1054-1058.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.08.003. Epub 2011 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 21550136]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKiyosaki K,Nakada C,Hijiya N,Tsukamoto Y,Matsuura K,Nakatsuka K,Daa T,Yokoyama S,Imaizumi M,Moriyama M, Analysis of p53 mutations and the expression of p53 and p21WAF1/CIP1 protein in 15 cases of sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid. Investigative ophthalmology [PubMed PMID: 19628749]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaumüller S, Herwig MC, Mangold E, Holz FC, Loeffler KU. Sebaceous gland carcinoma of the eyelid masquerading as a cutaneous horn in Li--Fraumeni syndrome. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2011 Oct:95(10):1470, 1478. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2009.175158. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20693561]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePrieto-Granada C, Rodriguez-Waitkus P. Sebaceous Carcinoma of the Eyelid. Cancer control : journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2016 Apr:23(2):126-32 [PubMed PMID: 27218789]

Schadendorf D, van Akkooi ACJ, Berking C, Griewank KG, Gutzmer R, Hauschild A, Stang A, Roesch A, Ugurel S. Melanoma. Lancet (London, England). 2018 Sep 15:392(10151):971-984. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31559-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30238891]

Garcia-Diaz A,Shin DS,Moreno BH,Saco J,Escuin-Ordinas H,Rodriguez GA,Zaretsky JM,Sun L,Hugo W,Wang X,Parisi G,Saus CP,Torrejon DY,Graeber TG,Comin-Anduix B,Hu-Lieskovan S,Damoiseaux R,Lo RS,Ribas A, Interferon Receptor Signaling Pathways Regulating PD-L1 and PD-L2 Expression. Cell reports. 2017 May 9; [PubMed PMID: 28494868]

Davies H, Bignell GR, Cox C, Stephens P, Edkins S, Clegg S, Teague J, Woffendin H, Garnett MJ, Bottomley W, Davis N, Dicks E, Ewing R, Floyd Y, Gray K, Hall S, Hawes R, Hughes J, Kosmidou V, Menzies A, Mould C, Parker A, Stevens C, Watt S, Hooper S, Wilson R, Jayatilake H, Gusterson BA, Cooper C, Shipley J, Hargrave D, Pritchard-Jones K, Maitland N, Chenevix-Trench G, Riggins GJ, Bigner DD, Palmieri G, Cossu A, Flanagan A, Nicholson A, Ho JW, Leung SY, Yuen ST, Weber BL, Seigler HF, Darrow TL, Paterson H, Marais R, Marshall CJ, Wooster R, Stratton MR, Futreal PA. Mutations of the BRAF gene in human cancer. Nature. 2002 Jun 27:417(6892):949-54 [PubMed PMID: 12068308]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaulson KG, Tegeder A, Willmes C, Iyer JG, Afanasiev OK, Schrama D, Koba S, Thibodeau R, Nagase K, Simonson WT, Seo A, Koelle DM, Madeleine M, Bhatia S, Nakajima H, Sano S, Hardwick JS, Disis ML, Cleary MA, Becker JC, Nghiem P. Downregulation of MHC-I expression is prevalent but reversible in Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer immunology research. 2014 Nov:2(11):1071-9. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0005. Epub 2014 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 25116754]

Becker JC, Stang A, Hausen AZ, Fischer N, DeCaprio JA, Tothill RW, Lyngaa R, Hansen UK, Ritter C, Nghiem P, Bichakjian CK, Ugurel S, Schrama D. Epidemiology, biology and therapy of Merkel cell carcinoma: conclusions from the EU project IMMOMEC. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII. 2018 Mar:67(3):341-351. doi: 10.1007/s00262-017-2099-3. Epub 2017 Nov 30 [PubMed PMID: 29188306]

Shuda M, Chang Y, Moore PS. Merkel cell polyomavirus-positive Merkel cell carcinoma requires viral small T-antigen for cell proliferation. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2014 May:134(5):1479-1481. doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.483. Epub 2013 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 24217011]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLunder EJ, Stern RS. Merkel-cell carcinomas in patients treated with methoxsalen and ultraviolet A radiation. The New England journal of medicine. 1998 Oct 22:339(17):1247-8 [PubMed PMID: 9786759]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDass SE, Huizenga T, Farshchian M, Mehregan DR. Comparison of SOX-10, HMB-45, and Melan-A in Benign Melanocytic Lesions. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2021:14():1419-1425. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S333376. Epub 2021 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 34675577]

El Shabrawi-Caelen L, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Melan-A: not a helpful marker in distinction between melanoma in situ on sun-damaged skin and pigmented actinic keratosis. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2004 Oct:26(5):364-6 [PubMed PMID: 15365366]

Sunjaya AP, Sunjaya AF, Tan ST. The Use of BEREP4 Immunohistochemistry Staining for Detection of Basal Cell Carcinoma. Journal of skin cancer. 2017:2017():2692604. doi: 10.1155/2017/2692604. Epub 2017 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 29464122]

Sinard JH. Immunohistochemical distinction of ocular sebaceous carcinoma from basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1999 Jun:117(6):776-83 [PubMed PMID: 10369589]

Lagler CN, Freitag SK. Management of periocular actinic keratosis: a review of practice patterns among ophthalmic plastic surgeons. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2012 Jul-Aug:28(4):277-81. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e318257f5f2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22785585]

Kahana A, Worden FP, Elner VM. Vismodegib as eye-sparing adjuvant treatment for orbital basal cell carcinoma. JAMA ophthalmology. 2013 Oct:131(10):1364-6. doi: 10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2013.4430. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23907144]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSu MG, Potts LB, Tsai JH. Treatment of periocular basal cell carcinoma with neoadjuvant vismodegib. American journal of ophthalmology case reports. 2020 Sep:19():100755. doi: 10.1016/j.ajoc.2020.100755. Epub 2020 May 23 [PubMed PMID: 32490287]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOzolins M, Williams HC, Armstrong SJ, Bath-Hextall FJ. The SINS trial: a randomised controlled trial of excisional surgery versus imiquimod 5% cream for nodular and superficial basal cell carcinoma. Trials. 2010 Apr 21:11():42. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-42. Epub 2010 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 20409337]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBath-Hextall F, Ozolins M, Armstrong SJ, Colver GB, Perkins W, Miller PS, Williams HC, Surgery versus Imiquimod for Nodular Superficial basal cell carcinoma (SINS) study group. Surgical excision versus imiquimod 5% cream for nodular and superficial basal-cell carcinoma (SINS): a multicentre, non-inferiority, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2014 Jan:15(1):96-105. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70530-8. Epub 2013 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 24332516]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWilliams HC, Bath-Hextall F, Ozolins M, Armstrong SJ, Colver GB, Perkins W, Miller PSJ, Surgery Versus Imiquimod for Nodular and Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma (SINS) Study Group. Surgery Versus 5% Imiquimod for Nodular and Superficial Basal Cell Carcinoma: 5-Year Results of the SINS Randomized Controlled Trial. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2017 Mar:137(3):614-619. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2016.10.019. Epub 2016 Dec 5 [PubMed PMID: 27932240]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceInaba K, Ito Y, Suzuki S, Sekii S, Takahashi K, Kuroda Y, Murakami N, Morota M, Mayahara H, Sumi M, Uno T, Itami J. Results of radical radiotherapy for squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Journal of radiation research. 2013 Nov 1:54(6):1131-7. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrt069. Epub 2013 Jun 7 [PubMed PMID: 23750022]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYin VT, Pfeiffer ML, Esmaeli B. Targeted therapy for orbital and periocular basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2013 Mar-Apr:29(2):87-92. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0b013e3182831bf3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23446297]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceEl-Sawy T, Sabichi AL, Myers JN, Kies MS, William WN, Glisson BS, Lippman S, Esmaeli B. Epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors for treatment of orbital squamous cell carcinoma. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 2012 Dec:130(12):1608-11. doi: 10.1001/archophthalmol.2012.2515. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23229707]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRoss AH, Kennedy CT, Collins C, Harrad RA. The use of imiquimod in the treatment of periocular tumours. Orbit (Amsterdam, Netherlands). 2010 Apr:29(2):83-7. doi: 10.3109/01676830903294909. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20394545]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFreitag SK, Aakalu VK, Tao JP, Wladis EJ, Foster JA, Sobel RK, Yen MT. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy for Eyelid and Conjunctival Malignancy: A Report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2020 Dec:127(12):1757-1765. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2020.07.031. Epub 2020 Jul 19 [PubMed PMID: 32698034]

Savar A, Ross MI, Prieto VG, Ivan D, Kim S, Esmaeli B. Sentinel lymph node biopsy for ocular adnexal melanoma: experience in 30 patients. Ophthalmology. 2009 Nov:116(11):2217-23. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.04.012. Epub 2009 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 19766318]

Davis LE, Shalin SC, Tackett AJ. Current state of melanoma diagnosis and treatment. Cancer biology & therapy. 2019:20(11):1366-1379. doi: 10.1080/15384047.2019.1640032. Epub 2019 Aug 1 [PubMed PMID: 31366280]

Ralli M, Botticelli A, Visconti IC, Angeletti D, Fiore M, Marchetti P, Lambiase A, de Vincentiis M, Greco A. Immunotherapy in the Treatment of Metastatic Melanoma: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Journal of immunology research. 2020:2020():9235638. doi: 10.1155/2020/9235638. Epub 2020 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 32671117]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaverakis E, Cornelius LA, Bowen GM, Phan T, Patel FB, Fitzmaurice S, He Y, Burrall B, Duong C, Kloxin AM, Sultani H, Wilken R, Martinez SR, Patel F. Metastatic melanoma - a review of current and future treatment options. Acta dermato-venereologica. 2015 May:95(5):516-24. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2035. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25520039]

Peters GB 3rd, Meyer DR, Shields JA, Custer PL, Rubin PA, Wojno TH, Bersani TA, Tanenbaum M. Management and prognosis of Merkel cell carcinoma of the eyelid. Ophthalmology. 2001 Sep:108(9):1575-9 [PubMed PMID: 11535453]

Sniegowski MC, Warneke CL, Morrison WH, Nasser QJ, Frank SJ, Pfeiffer ML, El-Sawy T, Esmaeli B. Correlation of American Joint Committee on Cancer T category for eyelid carcinoma with outcomes in patients with periocular Merkel cell carcinoma. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2014 Nov-Dec:30(6):480-5. doi: 10.1097/IOP.0000000000000153. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24841735]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVoog E, Biron P, Martin JP, Blay JY. Chemotherapy for patients with locally advanced or metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. Cancer. 1999 Jun 15:85(12):2589-95 [PubMed PMID: 10375107]

Schlaak M, Podewski T, Von Bartenwerffer W, Kreuzberg N, Bangard C, Mauch C, Kurschat P. Induction of durable responses by oral etoposide monochemotherapy in patients with metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma. European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2012 Mar-Apr:22(2):187-91. doi: 10.1684/ejd.2011.1634. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22240092]

Jouary T, Lalanne N, Siberchicot F, Ricard AS, Versapuech J, Lepreux S, Delaunay M, Taieb A. Neoadjuvant polychemotherapy in locally advanced Merkel cell carcinoma. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology. 2009 Sep:6(9):544-8. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.109. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19707243]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceToto V, Colapietra A, Alessandri-Bonetti M, Vincenzi B, Devirgiliis V, Panasiti V, Persichetti P. Upper eyelid Merkel cell carcinoma treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy and surgical excision. Archives of craniofacial surgery. 2019 Apr:20(2):121-125. doi: 10.7181/acfs.2018.02089. Epub 2019 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 31048649]

Garcia GA, Kossler AL. Avelumab as an Emerging Therapy for Eyelid and Periocular Merkel Cell Carcinoma. International ophthalmology clinics. 2020 Spring:60(2):91-102. doi: 10.1097/IIO.0000000000000306. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32205656]

Kokoska ER, Kokoska MS, Collins BT, Stapleton DR, Wade TP. Early aggressive treatment for Merkel cell carcinoma improves outcome. American journal of surgery. 1997 Dec:174(6):688-93 [PubMed PMID: 9409598]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFerreira TA, Pinheiro CF, Saraiva P, Jaarsma-Coes MG, Van Duinen SG, Genders SW, Marinkovic M, Beenakker JM. MR and CT Imaging of the Normal Eyelid and its Application in Eyelid Tumors. Cancers. 2020 Mar 12:12(3):. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030658. Epub 2020 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 32178233]

Go CC, Kim DH, Go BC, McGeehan B, Briceño CA. Clinicopathologic Characteristics and Prognostic Factors Impacting Survival in Melanoma of the Eyelid. American journal of ophthalmology. 2022 Feb:234():71-80. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.07.031. Epub 2021 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 34343490]

Quaedvlieg PJ, Tirsi E, Thissen MR, Krekels GA. Actinic keratosis: how to differentiate the good from the bad ones? European journal of dermatology : EJD. 2006 Jul-Aug:16(4):335-9 [PubMed PMID: 16935787]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChen GJ, Feldman SR, Williford PM, Hester EJ, Kiang SH, Gill I, Fleischer AB Jr. Clinical diagnosis of actinic keratosis identifies an elderly population at high risk of developing skin cancer. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2005 Jan:31(1):43-7 [PubMed PMID: 15720095]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWong VA, Marshall JA, Whitehead KJ, Williamson RM, Sullivan TJ. Management of periocular basal cell carcinoma with modified en face frozen section controlled excision. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2002 Nov:18(6):430-5 [PubMed PMID: 12439056]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDonaldson MJ, Sullivan TJ, Whitehead KJ, Williamson RM. Squamous cell carcinoma of the eyelids. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2002 Oct:86(10):1161-5 [PubMed PMID: 12234899]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBoniuk M, Zimmerman LE. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid, eyebrow, caruncle, and orbit. Transactions - American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology. American Academy of Ophthalmology and Otolaryngology. 1968 Jul-Aug:72(4):619-42 [PubMed PMID: 5706692]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRao NA, Hidayat AA, McLean IW, Zimmerman LE. Sebaceous carcinomas of the ocular adnexa: A clinicopathologic study of 104 cases, with five-year follow-up data. Human pathology. 1982 Feb:13(2):113-22 [PubMed PMID: 7076199]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDoxanas MT, Green WR. Sebaceous gland carcinoma. Review of 40 cases. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1984 Feb:102(2):245-9 [PubMed PMID: 6696670]