Introduction

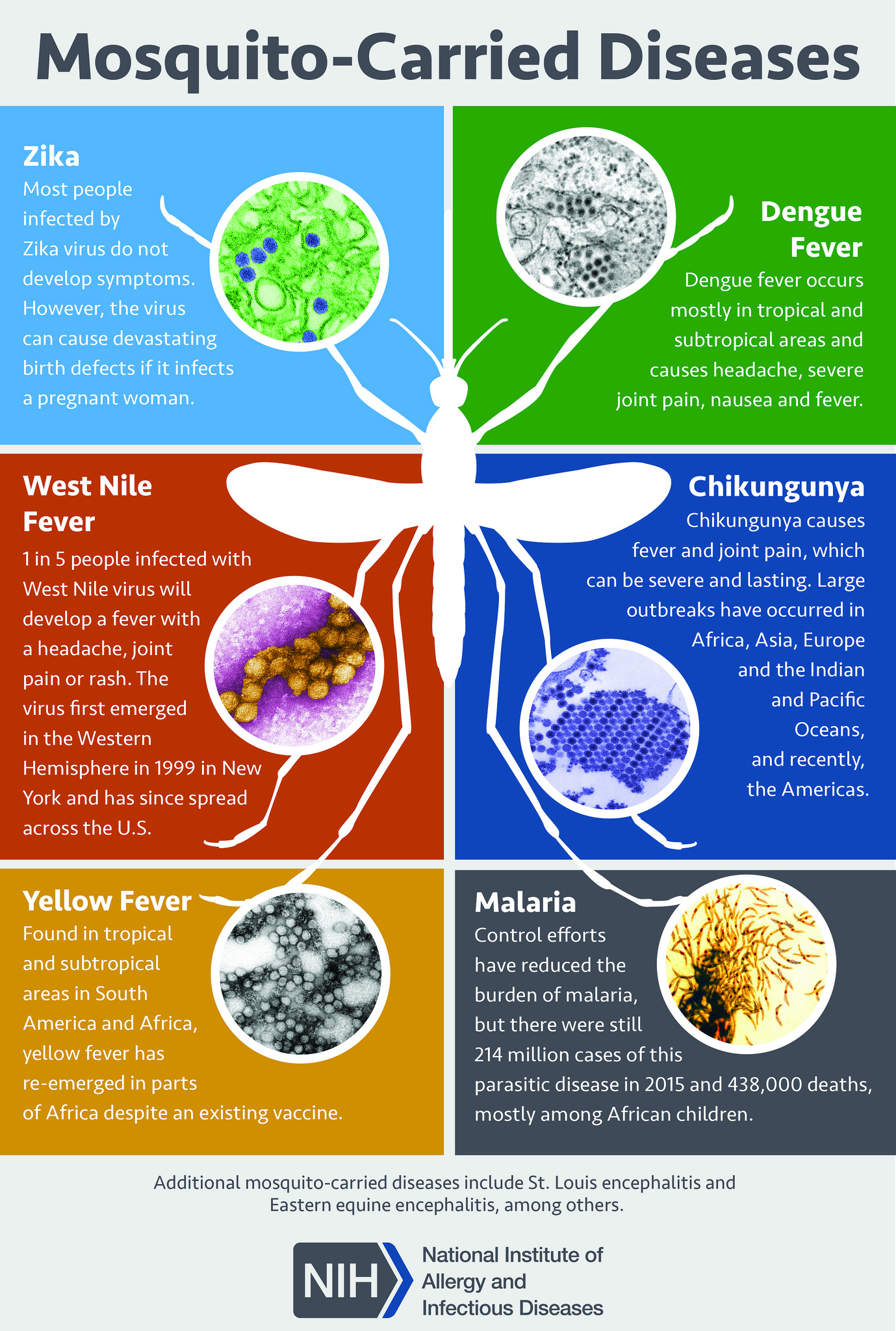

Plasmodium ovale is a cause of non-falciparum malaria infection. Non-falciparum malaria is due to infection caused by Plasmodium species other than P. falciparum. Other causes of non-falciparum malaria infection include P. vivax, P. malariae, and P. knowlesi. Malaria is a protozoan disease transmitted by the bite of infected Anopheles mosquitoes. [1] It is the most important cause of human parasitic diseases. It is transmitted by mosquitoes in 107 countries, affecting more than 3 billion people and causing 1 to 3 million deaths each year. P. ovale malaria is endemic to tropical western Africa. It rarely causes severe illness or death. [2]

To avoid the morbidity and mortality of malaria, prompt diagnosis, and treatment are necessary. P. falciparum is often resistant to chloroquine and can quickly be fatal. The plasmodium species can be differentiated by its morphology on a blood smear. P. falciparum is often associated with high levels of parasitemia and the 'banana-shaped' gametocytes. About 5% to 10% of patients with malaria are infected with more than a single plasmodium species. Each plasmodium species has a geographical area of endemicity, but some overlap is common.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

P. ovale malaria-like other types of malaria infection begins when female Anopheles mosquito bites and inoculates plasmodial sporozoites from its salivary gland during feeding. P. ovale may be composed of two coexisting species: Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri. [3]

Malaria is acquired after a bite from a mosquito. The mosquito transmits plasmodia from its saliva into the host while ingesting a blood meal. The plasmodia then enter the red blood cells and feed on the hemoglobin. Some parasites will become dormant, and others will remain active, and thus the synchronous pattern of clinical patterns in patients with malaria. The anopheles mosquitoes carrying the plasmodia only bites between dusk to dawn. Both P ovale and P vivax have a dormant phase that resides in the liver and emerges at a later time. Thus, when treating these species, one also needs to have treatment to kill the dormant protozoa. The malaria parasites breakdown hemoglobin and other proteins, including glucose, which can result in lactic acidosis and hypoglycemia. The plasmodia can also lyse both infected and uninfected red blood cells, leading to anemia and splenomegaly.

The risk of infection depends on the use of precautions (nets, DEET) and the intensity of transmission. Most healthy individuals can clear the parasite, but in those with immunosuppression, the parasites may continue to multiply. A small number of parasites will become gametocytes, which have the ability to undergo sexual reproduction when ingested by the mosquito. They can then develop into infective sporozoites, which will allow for the continuation of the cycle transmission after the mosquito has a blood meal in a new host.

The incubation period for P. falciparum is 30 days, which allows for continued antimalarial prophylaxis for at least four weeks after return from an endemic area. Rare reports of P. falciparum infections occurring 12 months later have also been reported. The incubation period for P. ovale and P. vivax varies from a few weeks to several months.

Protective Factors

Individuals with the sickle cell trait, hemoglobin C, thalassemias, and G6PD deficiency are protected against death from P. falciparum malaria. However, the degree of protection is variable. Some individuals living in endemic areas may develop partial immunity following repeated exposure to mosquitoes. This partial immunity lessens the symptoms and intensity of the infection. However, this immunity is lost when the individual moves away from the area.

Epidemiology

Malaria is present throughout most of the tropical areas of the world. P. ovale malaria is endemic to tropical Western Africa. It is relatively unusual outside of Africa and comprises less than 1% of isolates where found. It is also seen in the Philippines, Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea, but is relatively rare in these areas. [4] One survey in Indonesia, including more than 15,000 blood smears, noted 34 individuals with P. ovale infection, the frequency of P. ovale relative to P. falciparum, and P. vivax was a ratio less than 1:1000. [5] Reports of severe P. ovale malaria are rare, possibly due to the relative rarity of P. ovale infection.

In many parts of Africa and Asia, malaria and HIV infection coexist; the combination usually leads to poorer outcomes than either infection alone.

Malaria is equally likely in both genders. However, P. falciparum is known to have high morbidity and mortality during pregnancy. Fetal complications can include anemia, low birth weight, death, or premature birth.

Pathophysiology

The life cycle of P. ovale includes hypnozoites, which are dormant stages in the liver. These stages can be reactivated in weeks, months, or years after the initial infection, causing disease relapse.

Microscopic motile forms of malarial parasites are carried rapidly via the bloodstream to the liver. While in the liver, they invade hepatic parenchymal cells and begin a period of asexual reproduction. This process is known as an intrahepatic or pre-erythrocytic stage. P. ovale typically spends nine days in the pre-erythrocytic stage leading to the formation of sporozoites. P. ovale spends about 50 hours in an erythrocytic cycle. By the end of the 50 hours, the parasite has consumed nearly all of the hemoglobin and grown to occupy most of the red blood cells. At this stage, it is called a schizont. A single P. ovale sporozoite may produce about 15,000 daughter merozoites per infected hepatocyte.

Some P. ovale schizonts rupture and release merozoites into the circulation. Merozoites then invade red blood cells. While in the red blood cells, merozoites mature from ring forms to trophozoites and then to multinucleated schizonts. This state of maturation is called the erythrocytic stage. Schizonts that remain dormant are called hypnozoites. Hypnozoites are a dormant stage in the liver that can be seen in P. ovale as well as P. vivax infection. This dormant liver stage does not cause any clinical manifestations. Reactivation and release of hypnozoites into the circulation can lead to the late onset of the disease or relapse that can occur up to several months after the initial malaria infection.

Immediately after releasing of P. ovale from the liver, some merozoites develop into morphologically distinct male or female gametocytes that can transmit malaria infection. The Anopheles mosquito ingests these cells during a blood meal. The male and female gametocytes mature and form a zygote in the midgut of the mosquito. The zygote matures by asexual division and eventually releases sporozoites. The sporozoites then relocate to the mosquito's salivary glands. The mosquito completes its cycle of transmission by inoculating another human at the next feeding.

Histopathology

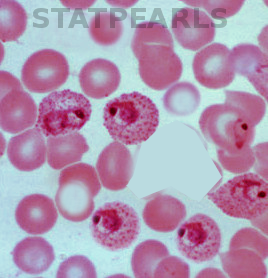

P. ovale typically infects young red blood cells, called reticulocytes. Giemsa stain reveals Schuffner dots under light microscopy. Infected erythrocytes are usually larger than normal. They can also be round, oval, or fimbriated. Trophozoites may be compact or irregularly shaped with sturdy cytoplasm and large chromatin dots. P. ovale gametophytes are usually round to oval, while P. ovale schizonts have 4 to 16 merozoites with dark brown pigment.

History and Physical

A detailed history is essential to the timely and successful diagnosis of P. ovale malaria. Prompt and accurate diagnosis of this disease is critical for appropriate treatment to reduce associated morbidity and mortality. Initial symptoms are nonspecific. Patients usually present with a headache, fever, malaise, muscle aches, fatigue, diaphoresis (sweating), cough, anorexia, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and arthralgia. [6] Nausea, vomiting, and orthostatic hypotension are common.

Malaria should be suspected in the context of fever (temperature greater than or equal to 37.5 C) and relevant epidemiologic exposure, including residence in or travel to an area where malaria is endemic. [7] Although a patient's headache may be severe, there is no neck stiffness or photophobia like in meningitis. Nausea, vomiting, and orthostatic hypotension are common. When a patient presents with fever, chills, and rigors that occur at a regular interval, it suggests P. ovale malaria.

Clinical manifestations of severe malaria may occur with any malaria species, in the presence or absence of coinfection with P. falciparum. [8] These manifestations include hemodynamic instability, pulmonary edema, hemolysis, severe anemia, coagulopathy, hypoglycemia, metabolic acidosis, renal failure, hepatic dysfunction, altered mental status, focal neurological deficits, and seizures. Physical findings may include pallor, petechiae, jaundice, hepatomegaly, and splenomegaly. Diagnostic evaluations of severe malaria include parasitemia greater than or equal to 4% to 10%, anemia, thrombocytopenia, coagulopathy, elevated transaminases, elevated BUN/creatinine, acidosis, and hypoglycemia. [9] Although reports of severe P. ovale malaria are rare, splenic rupture, thrombocytopenia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation have been associated with P. ovale infection. [10]

Evaluation

For a patient with suspected P. ovale infection, the diagnostic method of choice is blood smear microscopy. Suspected malaria should be confirmed with a parasitologic diagnosis whenever possible. Microscopy (visualization of parasites in stained blood smears) and rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), which detect antigen or antibody, are clinical tools for parasite-based diagnosis. Detection of parasites on Giemsa-stained blood smears by light microscopy is the ideal method for laboratory confirmation of malaria. [11]

At least two thick and thin blood smears should be prepared as soon as possible after blood collection. Delay in the preparation of smears can result in changes in parasite morphology and staining characteristics. Giemsa stain reveals Schuffner dots. Microscopy allows identification of the Plasmodium species as well as quantification of parasitemia. P. ovale infects only young erythrocytes, so parasite density for these species is typically lower. A parasitemia of greater than or equal to 5% is very unlikely with P. ovale or any other Plasmodium species except P. falciparum. The sensitivity of microscopy can be excellent, with the detection of malaria parasites at densities as low as 4 to 20 parasites per microliter of blood. [12]

RDTs should be used if microscopy is not available. RDTs for the detection of malaria parasite antigens are used in resource-limited endemic settings due to their accuracy and ease of use. They require no electricity or laboratory infrastructure and yield results within 15 to 20 minutes. RDTs provide a qualitative result but cannot provide quantitative information regarding parasite density. RDTs that detect antibodies produced by an infected host is also available, but these are less useful for diagnosing acute infection. There are no RDTs for definitive diagnosis of P. ovale.

Polymerase chain reaction is primarily a research tool. It typically detects as low as one parasite per microliter. Polymerase chain reaction diagnosis with a negative RDT may be useful where competent malaria microscopy is not available. [13]

Treatment / Management

Treatment of non-falciparum malaria consists of treating the erythrocytic forms. Also, the treatment of infections caused by P. ovale requires eradication of liver hypnozoites to prevent relapse of the infection. Patients with uncomplicated infection due to P. ovale, and in the absence of other comorbidities, can usually be managed on an outpatient basis. Parasitemia should be monitored during treatment to confirm adequate response to therapy. Daily blood smears are appropriate to document declining parasite density until no parasitemia is detected or until seven days of treatment have been completed. Patients on malaria prophylaxis who develop malaria infection should receive a different medication for treatment.

Chloroquine and or an artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) are used to treat P. ovale infection and other non-falciparum malaria infections. In areas with no endemic P. falciparum malaria, and chloroquine resistance remains low, chloroquine may be used with monitoring. ACT should be implemented when the chloroquine treatment failure rate at day 28 is greater than 10%.

Gametocytes of non-falciparum malaria species, including P. ovale, are susceptible to chloroquine. Chloroquine is highly effective against erythrocytic forms of P. ovale malaria infection. [14] Patients with mixed infections that include P. falciparum should receive definitive treatment for P. falciparum.

Primaquine is required to eradicate the hypnozoite liver stages of P. ovale. [15] Primaquine should be started after the fever has subsided, and normal glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase status has been confirmed.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

- Dengue fever

- Chikungunya

- Meningitis

- Pneumonia

- Sepsis due to bacteremia

- Typhoid fever

- Leptospirosis

- Viral hemorrhagic fever

Prognosis

Most healthy patients who develop uncomplicated malaria have a full recovery within 3-7 days. However, P. falciparum carries a poor prognosis and has a high mortality rate, if untreated

Complications

The majority of complications are associated with P. falciparum and include the following:

- Pulmonary edema

- Cerebral malaria

- Renal dysfunction

- Anemia

- Death

- Seizures

- Hypoglycemia

- Hemoglobinuria

- Lactic acidosis

- Thrombocytopenia

- Splenic rupture

The majority of deaths occur in children less than five years of age.

Pearls and Other Issues

The P. ovale life cycle includes hypnozoites, which are dormant stages in the liver that can lead to relapse. The presence of hypnozoites in the liver does not cause systemic infection. Symptoms of relapse occur when reactivated hypnozoites are released into the systemic circulation. P. ovale malaria is not chloroquine-resistant. Relapse due to P. ovale is relatively rare and may be prevented by the administration of presumptive anti-relapse therapy like primaquine.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In many western countries, malaria is rare. The interprofessional team must remain diligent and consider screening questions to help diagnose and evaluate potential world travelers that might be infected. Once a diagnosis is made, a team approach of clinicians, nurses, and a pharmacist working to make sure the patient continues treatment will provide the best patient outcome. The key to managing malaria is to prevent it in the first place.

The pharmacist should recommend chemoprophylaxis to travelers going to visit endemic areas. In addition, the pharmacist should emphasize the importance of medication compliance. They should also check for contraindications and drug-drug interactions.

The nurse should educate the patient on the use of DEET, mosquito nets, and wearing appropriate garments when venturing outside.

The public health nurse should educate homeowners on removing all standing water near the home and getting rid of the trash that acts as a breeding ground for mosquitoes. When a traveler returns from an endemic area with fever, an infectious disease consult should be obtained. The earlier the infection is diagnosed, the better the outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mace KE, Arguin PM, Tan KR. Malaria Surveillance - United States, 2015. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Surveillance summaries (Washington, D.C. : 2002). 2018 May 4:67(7):1-28. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.ss6707a1. Epub 2018 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 29723168]

Tomar LR, Giri S, Bauddh NK, Jhamb R. Complicated malaria: a rare presentation of Plasmodium ovale. Tropical doctor. 2015 Apr:45(2):140-2. doi: 10.1177/0049475515571989. Epub 2015 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 25672340]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSutherland CJ, Tanomsing N, Nolder D, Oguike M, Jennison C, Pukrittayakamee S, Dolecek C, Hien TT, do Rosário VE, Arez AP, Pinto J, Michon P, Escalante AA, Nosten F, Burke M, Lee R, Blaze M, Otto TD, Barnwell JW, Pain A, Williams J, White NJ, Day NP, Snounou G, Lockhart PJ, Chiodini PL, Imwong M, Polley SD. Two nonrecombining sympatric forms of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium ovale occur globally. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2010 May 15:201(10):1544-50. doi: 10.1086/652240. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20380562]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKawamoto F, Liu Q, Ferreira MU, Tantular IS. How prevalent are Plasmodium ovale and P. malariae in East Asia? Parasitology today (Personal ed.). 1999 Oct:15(10):422-6 [PubMed PMID: 10481157]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaird JK, Purnomo, Masbar S. Plasmodium ovale in Indonesia. The Southeast Asian journal of tropical medicine and public health. 1990 Dec:21(4):541-4 [PubMed PMID: 2151542]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSvenson JE, MacLean JD, Gyorkos TW, Keystone J. Imported malaria. Clinical presentation and examination of symptomatic travelers. Archives of internal medicine. 1995 Apr 24:155(8):861-8 [PubMed PMID: 7717795]

Wilson ME, Weld LH, Boggild A, Keystone JS, Kain KC, von Sonnenburg F, Schwartz E, GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Fever in returned travelers: results from the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2007 Jun 15:44(12):1560-8 [PubMed PMID: 17516399]

Hwang J, Cullen KA, Kachur SP, Arguin PM, Baird JK. Severe morbidity and mortality risk from malaria in the United States, 1985-2011. Open forum infectious diseases. 2014 Mar:1(1):ofu034. doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofu034. Epub 2014 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 25734104]

Devarbhavi H, Alvares JF, Kumar KS. Severe falciparum malaria simulating fulminant hepatic failure. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2005 Mar:80(3):355-8 [PubMed PMID: 15757017]

Facer CA, Rouse D. Spontaneous splenic rupture due to Plasmodium ovale malaria. Lancet (London, England). 1991 Oct 5:338(8771):896 [PubMed PMID: 1681259]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAbanyie FA, Arguin PM, Gutman J. State of malaria diagnostic testing at clinical laboratories in the United States, 2010: a nationwide survey. Malaria journal. 2011 Nov 10:10():340. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-340. Epub 2011 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 22074250]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDowling MA, Shute GT. A comparative study of thick and thin blood films in the diagnosis of scanty malaria parasitaemia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 1966:34(2):249-67 [PubMed PMID: 5296131]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceProux S, Suwanarusk R, Barends M, Zwang J, Price RN, Leimanis M, Kiricharoen L, Laochan N, Russell B, Nosten F, Snounou G. Considerations on the use of nucleic acid-based amplification for malaria parasite detection. Malaria journal. 2011 Oct 28:10():323. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-10-323. Epub 2011 Oct 28 [PubMed PMID: 22034851]

Siswantoro H, Russell B, Ratcliff A, Prasetyorini B, Chalfein F, Marfurt J, Kenangalem E, Wuwung M, Piera KA, Ebsworth EP, Anstey NM, Tjitra E, Price RN. In vivo and in vitro efficacy of chloroquine against Plasmodium malariae and P. ovale in Papua, Indonesia. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2011 Jan:55(1):197-202. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01122-10. Epub 2010 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 20937779]

John GK, Douglas NM, von Seidlein L, Nosten F, Baird JK, White NJ, Price RN. Primaquine radical cure of Plasmodium vivax: a critical review of the literature. Malaria journal. 2012 Aug 17:11():280. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-11-280. Epub 2012 Aug 17 [PubMed PMID: 22900786]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence