Introduction

An episiotomy, a surgical incision made at the end of the second stage of labor to widen the vaginal opening, helps facilitate delivery.[1][2] Ideally, an episiotomy relieves pressure on the perineum during difficult deliveries, resulting in an easily repairable incision when compared to uncontrolled vaginal trauma.[3] The primary types of episiotomy are the midline (or median), which begins near the center of the perineum and extends straight downward, and the mediolateral, which starts similarly but angles 60 degrees to the side.[1][2] Other less frequently used episiotomy incisions include the modified median, J-shaped, lateral, anterior, and radical.[4]

After childbirth, performing a thorough perineal examination is necessary to assess trauma, and a rectal examination is vital to detect any anal sphincter injuries. In the United States, episiotomy was a widely used technique until 2006, when the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) made a recommendation against its routine use. However, episiotomy still has select indications and should be performed based on clinical judgment and maternal or fetal factors. Episiotomies, particularly the midline type, are linked with higher rates of obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS).[1][2] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Obstetric Perineal Lacerations," for more information.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The female external genitalia includes the mons pubis, labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineal body, and vaginal vestibule. The perineal body is the region between the anus and the vaginal vestibular fossa. The perineum typically comprises the anatomic structures within the pelvic outlet, including the superficial and deep muscles of the perineal membrane, bordered by the ischial rami, pubic symphysis, ischial tuberosities, and sacrotuberous ligaments and coccyx. The perineal membrane is the most common site of laceration during childbirth.[1][5]

Vaginal and vulvar lacerations are typically superficial and do not require repair. However, episiotomy incisions and any resulting perineal lacerations can involve multiple anatomic structures; therefore, perineal lacerations are stratified according to severity, whereas vulvar and vaginal lacerations are not.[2] Most clinicians use the Sultan classification to stratify perineal lacerations into the following 4 primary categories:

- First Degree: superficial injury to the vaginal mucosa that may involve the perineal skin

- Second Degree: first-degree laceration involving the vaginal mucosa and perineal body

- Third Degree: second-degree laceration with the involvement of the anal sphincter complex, which can be further classified into the following 3 subcategories:

- Fourth Degree: Tearing of the anal sphincter complex and the rectal mucosa [6][7]

Severe perineal lacerations, which include third- and fourth-degree lacerations, are referred to as OASIS injuries.[8][1]

Indications

Routine episiotomy is no longer indicated due to the adverse effects associated with the procedure (eg, perineal pain, dyspareunia, and sexual dysfunction).[9][1] Episiotomy was considered necessary previously in certain cases where rapid delivery in the second stage was needed (eg, fetal distress, shoulder dystocia, or operative vaginal delivery).[10] However, evidence demonstrating a clear benefit in these settings is limited and inconclusive.[9]

The long-term effects studied in follow-up research regarding episiotomy revealed no difference in urinary issues, anal incontinence, or painful intercourse (ie, dyspareunia) between the spontaneous lacerations and episiotomy groups. Despite this, evidence remains limited, and larger trials are needed to clarify the role of episiotomy in complex deliveries.[7] Subsequently, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has stated that no definite indications for episiotomy have been established. Consequently, the current recommendation is to utilize restrictive episiotomy, in which episiotomy is considered based on clinical factors, including nonreassuring fetal heart tones and assisted vaginal births with vacuum or forceps, particularly in nulliparous patients. In these cases, studies have shown that mediolateral episiotomy significantly reduces the risk of obstetrical anal sphincter injuries.[9][11]

Contraindications

The routine use of episiotomy is not supported; therefore, the World Health Organization and ACOG recommend its restricted use.[8][1] Routine episiotomy was debated, with advocates claiming it could prevent unexpected severe tears.[3] However, studies demonstrated that not all women suffer significant perineal trauma during vaginal birth, and the routine use of episiotomy exposes patients to unnecessary surgical incisions and their associated complications. Even in emergent cases (eg, shoulder dystocia or instrumental-assisted deliveries), the evidence does not consistently support episiotomy’s ability to prevent severe tears. In some cases, severe perineal tears were found to occur despite episiotomy. Therefore, the selective use of episiotomy is recommended based on specific clinical considerations rather than routine practice.[1]

Equipment

When performing an episiotomy and its subsequent repair, the following equipment and preparation are necessary:

- Surgical scissors: Surgical or angled scissors are typically used to perform the episiotomy.[7]

- Lighting and tissue exposure: Adequate lighting and proper visualization are crucial for thorough examination and repair.[2]

- Anesthesia

- First and second-degree lacerations: Local anesthetic infiltration is usually sufficient.

- Obstetric anal sphincter injuries: Regional or general anesthesia may be required.[2]

- Disinfection: Use of Betadine or chlorhexidine solution to clean the perineal area before the episiotomy and the repair [2]

- Instruments and supplies

- Surgical glue

- Sutures

- Needle drivers

- Allis clamps

- Forceps

- Sterile gloves

- Sponges

- Suture scissors

- Foley catheter (for third- and fourth-degree lacerations) [2]

- Suture material: based on laceration type

- First-degree: 2-0 or 3-0 polyglactin or poliglecaprone

- Second-degree: 2-0 or 3-0 polyglactin

- Third-degree: 2-0 polyglactin, 3-0 polyglactin or polydioxanone

- Fourth-degree: 3-0 or 4-0 polyglactin or poliglecaprone [2]

- Monofilament sutures: Often preferred due to a reduced risk of infection.[2]

- Operating room access: May be required depending on the severity of the laceration [2]

Personnel

The following personnel may be involved during episiotomy procedures:

- Obstetric clinicians

- Family practice clinicians

- Midwives

- Labor and delivery nurses

- Anesthesiology clinicians

Preparation

Several key steps must be taken to ensure the patient's safety and comfort before performing an episiotomy and its repair. Proper lighting should be in place. Before starting the procedure, all surgical instruments, sponges, and sutures should be counted and prepared, and the vaginal area may be prepped with povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine to prevent postoperative infections.[2]

Clinicians should communicate the clinical indications for episiotomy and ensure that the patient consents to the procedure and its repair.[1][11][12] Additionally, the perineum should be assessed as the patient pushes, and the episiotomy method (eg, medial or mediolateral) should be determined.[11] Adequate anesthesia should be confirmed, and if additional pain control is needed, local anesthetic may be administered to the chosen episiotomy incision site.[3]

Technique or Treatment

Episiotomy is a surgical incision made in the perineum as the patient is actively pushing to facilitate delivery using either scissors or a scalpel.[3] Various types of episiotomy have been developed, with the midline and mediolateral being the most commonly used.

The technique for performing an episiotomy involves making the incision during the crowning of the fetal head when the perineal muscles are stretched thin. The clinician supports the perineum and uses scissors to make a single, deep cut during a contraction. Adequate anesthesia is essential, and precise timing and technique are necessary to minimize complications such as pain, infection, hematoma, and scarring, which can lead to long-term issues like dyspareunia.[3]

Several countries have developed protocols regarding episiotomies to reduce the incidence of OASI. These initiatives, including the OASI Care Bundle in the United Kingdom, advocate for clinician training in perineal protection and the use of mediolateral episiotomies. Additionally, devices like EPISCISSORS-60 have been developed in the United Kingdom to help maintain the ideal 60-degree incision angle, reducing the risk of OASI. Studies have demonstrated these protocols have led to a significant decrease in OASI rates and have positively impacted clinician practices and patient experiences.[7]

Types of Episiotomy

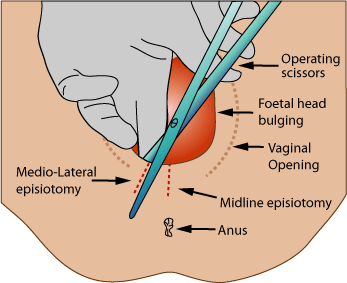

Each episiotomy technique is designed with specific considerations for the safety of both mother and child and to minimize complications, including anal sphincter injury (see Image. Episiotomy).[4] The different types of episiotomy incisions include:

- Median (midline) episiotomy

- Midline episiotomies are typically preferred in the United States.[7]

- The incision starts at the posterior fourchette and runs along the midline through the central tendon of the perineal body.

- The incision originates within 3 mm of the midline and is angled between 0 degrees and 25 degrees.

- The incision extends to about half the length of the perineum.[4]

- Modified-median episiotomy

- A variation of the median episiotomy.

- Two transverse incisions are added bilaterally, just above the anal sphincter, extending the median incision.

- The transverse cuts are perpendicular to the midline, with a total length of 2 to 5 cm.

- This approach aims to increase the vaginal outlet diameter by about 83% compared to a standard median episiotomy.[4]

- J-shaped episiotomy

- These incisions begin with a midline incision and curve laterally to avoid the anus.

- The initial incision is made along the midline, up to 2 to 5 cm from the anus.

- The cut is then curved towards the ischial tuberosity to divert the incision away from the anal sphincter.[4]

- Mediolateral episiotomy

- The incision begins at the midline of the posterior fourchette but is directed laterally and downward at a minimum angle of 60 degrees.

- This method is designed to avoid the anal sphincter and is typically directed toward the ischial tuberosity.[4]

- The mediolateral episiotomy is more common in Europe and usually results in a 45-degree angle postdelivery.[7]

- Lateral episiotomy

- This type begins further from the midline (>10 mm from the posterior fourchette) and is directed laterally.

- The cut is angled towards the ischial tuberosity, avoiding the midline and sphincter.[4]

- Radical lateral (Schuchardt incision)

- A deep and fully extended incision into one vaginal sulcus, curving downward and laterally around the rectum.

- Often used in gynecologic procedures, eg, radical vaginal hysterectomy or trachelectomy, but may occasionally be used for complicated deliveries.

- The incision originates >10 mm from the midline and extends laterally around the rectum.[4]

- Anterior episiotomy (deinfibulation)

- This type of episiotomy is performed during delivery in women who have undergone infibulation (ie, genital mutilation).

- The fused labia minora are incised along the midline until the external urethral meatus is reached.

- Care is taken not to cut the clitoris or surrounding tissue. The incision runs in the midline, directed towards the pubis.[4]

Episiotomy Repair

After every vaginal delivery, the perineum, vagina, and cervix should be carefully examined.[8] A digital rectal examination should be done with any severe laceration to assess the integrity and tone of the anal sphincter.[8] Proper closure of each of the layers of a second-degree laceration, including the vaginal epithelium, muscular, perineal body muscles, rectovaginal fascia, and perineal skin, which is typically the repair involved following an episiotomy, is crucial for successful healing and minimizing complications.[7]

Generally, for second-degree perineal lacerations, a continuous or running suture closure should be used over interrupted suturing to decrease postpartum pain and the possibility of the patient requiring suture removal.[1][13] The suture is used to reapproximate the vaginal mucosa to the level of the hymen. Once the hymen is restored attention is turned to the perineal body and submucosal region. After these areas are properly closed, the skin is reapproximated.[1][13] The following technique is typically recommended for this type of laceration:

- Anchor the suture distal to the apex of the laceration in the vaginal epithelium.

- Close the vaginal epithelium, underlying muscularis, and rectovaginal fascia with a nonlocking suture in a running fashion to the level of the hymenal ring.

- Then, using the same suture in the same fashion, close the bulbocavernosus and transverse perineal muscles from the axial plane parallel to the perineal muscles.

- Repair the subcuticular perineal skin with the same suture in a running fashion, working back up to the hymenal ring.

- Tie the suture knot behind the hymenal ring.

- Perform a rectal exam to confirm adequate repair of the laceration and no misplaced sutures.[2]

If an episiotomy is found to have extended into a third- or fourth-degree laceration, the appropriate OASIS repair should be performed. A Foley catheter should be placed before the repair is initiated. Additionally, preoperative antibiotics, typically a second-generation cephalosporin, should be administered to reduce infection risk and surgical instrument, sponge, and suture postoperative counts should be conducted.[7] Proper repair of third- and fourth-degree lacerations is more complex; clinical expertise and correct technique are essential to improve patient outcomes. The particular focus of OASIS lacerations is the reapproximation of the anal sphincter complex and rectal mucosa, depending on the severity of the injury.[7] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Obstetric Perineal Lacerations," for detailed information on the repair of these lacerations.

Postoperative Care

Clinicians should closely monitor patients immediately after perineal laceration repair for any anesthesia or postoperative complications and document the repair, including the type of laceration, the repair technique, and the suture materials used. Clinicians should inform the patient what type of repair was performed and ensure they understand the importance of follow-up care. Following OASIS repairs, patients are at a high risk for urinary retention. Therefore, a Foley catheter is recommended, along with a voiding trial on the first postoperative day, to assess bladder function.[7]

Pain management should include local cool packs applied to the perineum and topical anesthetic ointments or sprays. Oral analgesics, eg, acetaminophen or NSAIDs, are preferred over opioids which can cause constipation. In patients who have undergone OASIS repair, stool softeners or laxatives should be regularly administered for 6 weeks to prevent wound complications. Sitz baths twice daily until the first wound check are also beneficial.[7]

Given the risk of complications, including wound infection, dehiscence, and rectovaginal fistula, patients should be closely monitored during postpartum recovery. Women who have undergone obstetric anal sphincter injuries (OASIS) should be scheduled for a follow-up visit within 2 weeks.[7] Patients should be advised to report any abnormal symptoms, including foul-smelling vaginal discharge, dysuria, severe perineal or pelvic pain, fever, and heavy vaginal bleeding.[10]

Complications

Although intended to widen the vaginal opening and reduce perineal trauma during delivery, episiotomy carries risks such as perineal pain, dyspareunia, and sexual dysfunction. Complications include bleeding, infection, extended tears into the anal sphincter, scarring, and even more serious outcomes like vaginal prolapse or fistulas. In some cases, severe perineal tears occur despite episiotomy, raising questions about its effectiveness in preventing trauma. Episiotomy has also been associated with complications during future deliveries.[7]

Risk factors that increase the likelihood of complications include smoking, obesity, fourth-degree lacerations, operative vaginal deliveries, and the use of postpartum antibiotics. In cases where a woman is at a higher risk for complications related to perineal trauma or pelvic floor disorders, follow-up in a specialized clinic is beneficial. If any signs of anal sphincter dysfunction appear during recovery, an endoanal ultrasound should be performed to evaluate the extent of damage. If significant damage or persistent symptoms are noted, secondary anal sphincter repair might be necessary.[7]

Clinical Significance

Despite its benefits in some cases, the routine use of episiotomy has been debated. Research demonstrates that episiotomy may not reduce the severity of pelvic floor issues or improve long-term outcomes. Instead, episiotomy can increase the risk of anal incontinence and other complications, particularly if the incision extends into an OASIS injury. Selective use of episiotomy compared with its routine use during vaginal birth is associated with lower rates of posterior perineal trauma, less suturing, and fewer healing complications. Because of the severe complications that may result from this procedure or an inadequately repaired episiotomy, an in-depth knowledge of the appropriate indications, proper technique, and correct repair is essential to optimizing patient outcomes. Furthermore, preventative measures, including perineal massage in late pregnancy and intrapartum perineal support, should also be implemented to reduce the need for episiotomy.[7]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing an episiotomy and the postpartum repair requires a collaborative, interprofessional approach to enhance patient-centered care, outcomes, patient safety, and team performance. Physicians, midwives, and advanced practitioners must be skilled in performing these incisions and repairing lacerations, employing strategies to prevent severe injuries and ensuring timely intervention. Nurses are critical in assessing lacerations, providing immediate care, and supporting patients throughout healing. Pharmacists contribute by managing pain relief and recommending appropriate medication regimens to prevent infections. Clear and continuous interprofessional communication is essential to coordinate care effectively, ensuring that each team member is informed about the patient's condition and treatment plan. This cohesive teamwork promotes a holistic approach to care, addressing the physical and emotional needs of the patient, ultimately improving recovery and quality of life.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The nurse usually sets up the tray for episiotomy and assist the surgeon. Once the surgery is over, the nurse will often apply a dressing. In the post-delivery phase, the nurse will monitor the patient for pain and urinary incontinence. Patients receive training on how to take sitz baths and clean the perineum. If there is swelling, the nurse will apply ice packs which also decrease the pain. The sutures used to close an episiotomy do not require removal, and will reabsorb in the tissues within 6 to 8 weeks. Finally, patients must learn how to perform Kegel exercises to help tighten up the pelvic floor muscles.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

- Vital signs

- Symptoms and signs of wound infection

- Any abnormal discharge

- Pain score

- Urine output

- Patient ambulation and level of activity

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Episiotomy. This image depicts the various types of episiotomy incisions.

Jeremy Kemp, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Committee on Practice Bulletins-Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 198: Prevention and Management of Obstetric Lacerations at Vaginal Delivery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Sep:132(3):e87-e102. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002841. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30134424]

Schmidt PC, Fenner DE. Repair of episiotomy and obstetrical perineal lacerations (first-fourth). American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2024 Mar:230(3S):S1005-S1013. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.07.005. Epub 2023 May 2 [PubMed PMID: 37427859]

Jiang H, Qian X, Carroli G, Garner P. Selective versus routine use of episiotomy for vaginal birth. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Feb 8:2(2):CD000081. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000081.pub3. Epub 2017 Feb 8 [PubMed PMID: 28176333]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDoumouchtsis SK, de Tayrac R, Lee J, Daly O, Melendez-Munoz J, Lindo FM, Cross A, White A, Cichowski S, Falconi G, Haylen B. An International Continence Society (ICS)/ International Urogynecological Association (IUGA) joint report on the terminology for the assessment and management of obstetric pelvic floor disorders. International urogynecology journal. 2023 Jan:34(1):1-42. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05397-x. Epub 2022 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 36443462]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJeganathan AN, Cannon JW, Bleier JIS. Anal and Perineal Injuries. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2018 Jan:31(1):24-29. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1602176. Epub 2017 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 29379404]

Arnold MJ, Sadler K, Leli K. Obstetric Lacerations: Prevention and Repair. American family physician. 2021 Jun 15:103(12):745-752 [PubMed PMID: 34128615]

Okeahialam NA, Sultan AH, Thakar R. The prevention of perineal trauma during vaginal birth. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2024 Mar:230(3S):S991-S1004. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2022.06.021. Epub 2023 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 37635056]

Goh R, Goh D, Ellepola H. Perineal tears - A review. Australian journal of general practice. 2018 Jan-Feb:47(1-2):35-38. doi: 10.31128/AFP-09-17-4333. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29429318]

. Operative Vaginal Birth: ACOG Practice Bulletin Summary, Number 219. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2020 Apr:135(4):982-984. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003765. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32217970]

Choudhari RG, Tayade SA, Venurkar SV, Deshpande VP. A Review of Episiotomy and Modalities for Relief of Episiotomy Pain. Cureus. 2022 Nov:14(11):e31620. doi: 10.7759/cureus.31620. Epub 2022 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 36540434]

Okeahialam NA, Wong KW, Jha S, Sultan AH, Thakar R. Mediolateral/lateral episiotomy with operative vaginal delivery and the risk reduction of obstetric anal sphincter injury (OASI): A systematic review and meta-analysis. International urogynecology journal. 2022 Jun:33(6):1393-1405. doi: 10.1007/s00192-022-05145-1. Epub 2022 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 35426490]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAragaw FM, Belay DG, Endalew M, Asratie MH, Gashaw M, Tsega NT. Level of episiotomy practice and its disparity among primiparous and multiparous women in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in global women's health. 2023:4():1153640. doi: 10.3389/fgwh.2023.1153640. Epub 2023 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 38025985]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLeeman L, Spearman M, Rogers R. Repair of obstetric perineal lacerations. American family physician. 2003 Oct 15:68(8):1585-90 [PubMed PMID: 14596447]