Introduction

Livedoid vasculopathy is a rare vasculopathy typically characterized by bilateral lower limb lesions. The condition is believed to be caused by thrombus formation in the capillary vasculature due to increased thrombotic activity, decreased fibrinolytic activity, and endothelial damage.

Livedoid vasculopathy is 3 times more common in females than in males, especially in patients aged 15 to 50 years. Management involves identifying the lesion and differentiating it from other lower limb lesions, along with a skin biopsy to confirm the diagnosis.

There is no definitive first-line treatment, but general measures such as smoking cessation, wound care, and pharmacological measures like anticoagulants and antiplatelets have shown good results. Several newer and experimental therapies have shown promising results in resistant cases.[1][2][3]

In the past, livedoid vasculopathy has also been referred to as livedo vasculitis, livedoid vasculitis, and livedo reticularis with summer ulceration.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Vasculopathy occurs when a thrombus forms in the arterial lumen leading to compromised blood flow. It is distinct from vasculitis, which refers to primary inflammation of the vessel wall followed by fibrinoid necrosis. Livedoid vasculopathy is usually associated with phenomena that cause hypercoagulability and thrombus formation, including:

- Conditions associated with stasis: Chronic venous hypertension of the limbs, varicose veins (vasculopathy is not generally surrounded by livedo reticularis) [5]

- Autoimmune connective tissue diseases: Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, scleroderma, mixed connective tissue disease.

- Thrombophilias: Inherited causes (factor V Leiden variant, prothrombin gene G20210A mutation, protein C, protein S, and antithrombin deficiency, etc); acquired causes (acquired homocysteinemia, cryoglobulinemia, cryofibrinogenemia, acquired antiphospholipid antibody syndrome)

- Neoplasms: Myeloproliferative disorders, paraproteinemia, etc

- Idiopathic causes [3]

Epidemiology

Livedoid vasculopathy is a rare diagnosis with an approximate incidence of 1 in 1,00,000 per year. It is 3 times more common in females than in males. Most of the patients are 15 to 50 years old.[1] It is now established that there is an increased incidence of livedo vasculopathy during the summer months. It is also more frequently seen in pregnant women.[6]

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of livedoid vasculopathy can be explained by increased thrombotic and decreased fibrinolytic activity along with endothelial cell damage.

Biochemical mechanisms involving defects in the proteins and enzymes involved in the coagulation and fibrinolysis pathways can lead to increased platelet and fibrin-rich thrombi in the capillaries leading to its typical cutaneous manifestations.[2]

Some patients with livedoid vasculopathy have an associated condition that predisposes them to occlusion of the small vessels of the lower leg. An example of this is when homocysteinemia leads to DNA hypomethylation and prevents the action of histone deacetylase, which leads to transcriptional repression along with increased oxidant stress on cells due to increased expression of p66shc in endothelial cells.[7][8]

Histopathology

Livedoid vasculopathy is usually a clinical diagnosis, but a skin biopsy from a red papule or the edge of a new ulcer supports it. The most characteristic histological findings consist of thickening or hyalinization of superficial dermal vessels along with intraluminal fibrin deposits. Red blood cell extravasation and perivascular lymphocytic infiltration may be associated.[1][9]

A direct immunofluorescence is often performed, showing the deposition of immunoglobulin and complement components in the superficial, mid-dermal, and deep dermal vasculature. However, these findings are neither characteristic nor diagnostic of livedoid vasculopathy.[10]

History and Physical

The patient usually presents with a history of painful recalcitrant ulcers and whitish scars near the ankles, which are associated with a painful burning sensation. The prodrome of this burning pain is a pathognomonic feature in history. Usually, pure livedoid vasculopathy is a skin-limited manifestation; hence, no systemic symptoms are expected. However, lesions akin to livedoid vasculopathy are seen in autoimmune connective tissue diseases, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, and inherited thrombophilia; hence, a detailed history focusing on these associated diseases must be elucidated.[11]

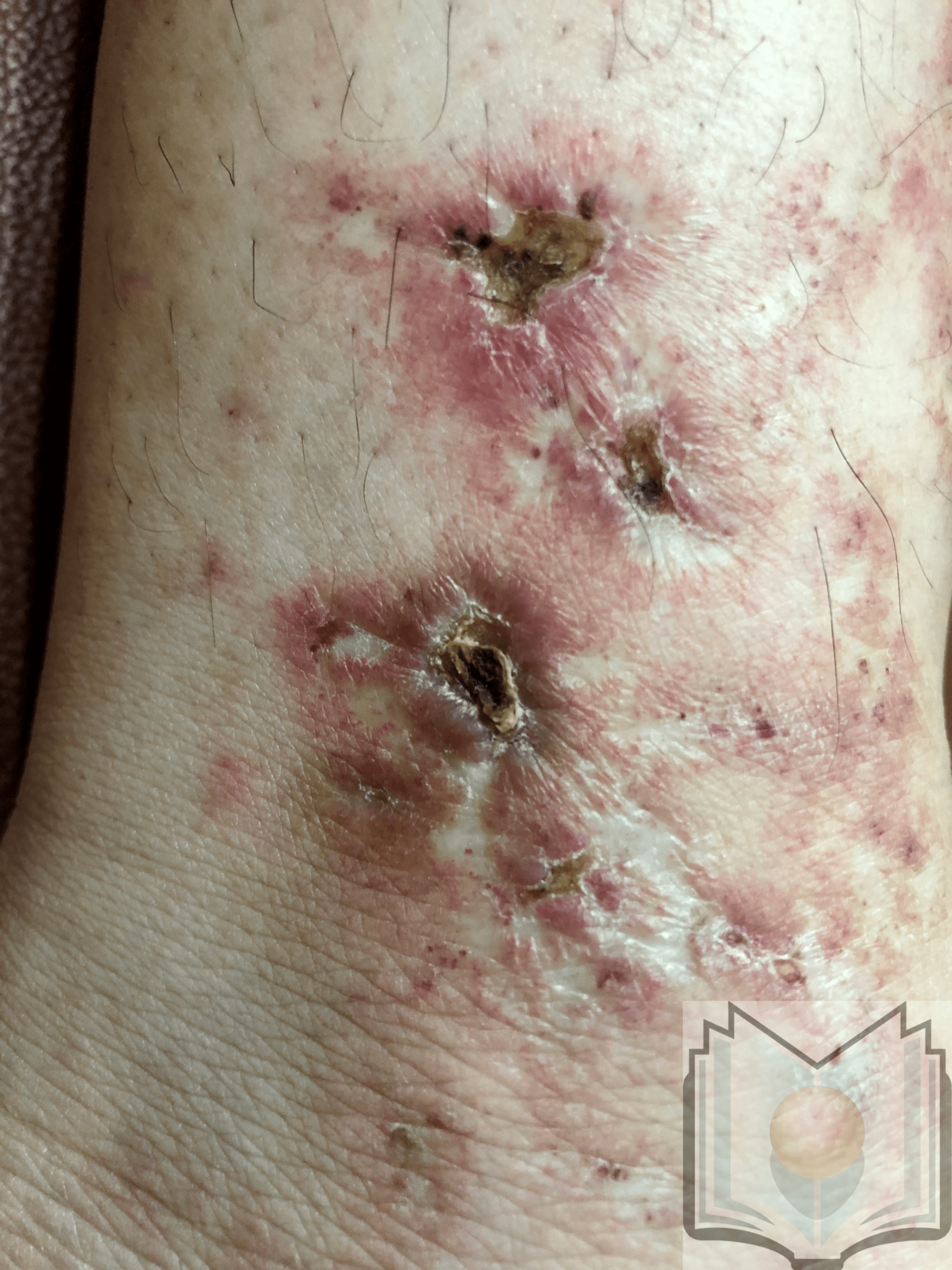

Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by punched-out ulcers in the perimalleolar area surrounded by lacy, reticular, reddish to violaceous streaks, also known as livedo reticularis.[12] These ulcers heal, forming porcelain white scars surrounded by telangiectasias and represent the vestiges of cutaneous infarction due to disturbed capillary microcirculation. These scars are known as atrophie blanche or capillaritis alba and are not specific to livedoid vasculopathy. Ulcers characterize the active stage of the disease, whereas livedo reticularis and livedo racemosa (broken net pattern) are precursors to ulceration. Painful purpuric ulcers with reticular pattern of lower extremities (PPURPLE) sums up the entire clinical spectrum of this condition. Retiform or stellate purpura is considered a hallmark lesion.[13] Most commonly, lesions can be seen in the perimalleolar area, but they can also be seen on the lower leg and foot. The disease is bilateral in most cases.[3]

Evaluation

The approach for evaluation of a patient presenting with lesions suspicious of livedoid vasculopathy should focus on confirming the diagnosis, ruling out close differentials, and a workup for associated conditions.

A skin biopsy, preferably a 3- to 4-mm punch biopsy from the margin of the ulcer or the surrounding livedo, is a must for confirming the diagnosis.

Ankle-brachial pressure index and lower limb venous doppler should be done to rule out chronic venous insufficiency.

Laboratory investigations should focus on ruling out the following:

Treatment / Management

The treatment approach for livedoid vasculopathy should aim at preventing ulceration, promoting rapid healing of existing ulcers, and pain relief.

General Measures

- Pain management: Pain relief is achieved by the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), tricyclic antidepressants like amitriptyline, gabapentin, pregabalin, and antiepileptics such as carbamazepine, as these drugs are known to relieve neuropathic pain.

- Intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG): Rapid relief of pain has been reported with the use of IVIG, which causes inhibition of thromboxane A2 and endothelin and thereby improves perfusion.

- Wound care: General principles of wound healing and management should be followed.

- Smoking cessation

- Compression therapy

Specific Pharmacological Measures

There are no definitive therapeutic guidelines for the management of livedoid vasculopathy. However, a combination of anticoagulants, antiplatelet medications, fibrinolytic therapies, and anabolic steroids are reported to be efficacious

Drugs by category

Examples of drugs used to treat livedoid vasculopathy include:

- Anti-platelet agents: Aspirin (325 mg/day), dipyridamole, and pentoxifylline (400 mg/day)

- Anticoagulants: Low molecular weight heparin, warfarin (with monitoring for the international normalized ratio [INR] of 2.0-3.0), rivaroxaban (20 mg/day), and direct thrombin inhibitors such as dabigatran

- Fibrinolytic therapies: Recombinant tissue plasminogen activator, danazol, and stanozolol [15]

- Immunomodulatory and immunosuppressive agents: IVIG, cyclosporine, doxycycline, dapsone (especially in myeloproliferative disorders), sulfasalazine, and psoralen plus ultraviolet A (PUVA)

- Vasodilators: Nifedipine, cilostazol

- Other: Hyperbaric oxygen therapy, ketanserin (quinazoline), alprostadil (prostaglandin analog) [1][3][16][17] (B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses for livedoid vasculopathy include:

Livedo Reticularis With Ulceration

This active stage is mimicked by cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) and often leads to a diagnostic dilemma. Cutaneous PAN is characterized by livedo racemosa, subcutaneous nodules, and starburst livedo. It is a medium-vessel cutaneous vasculitis. The presence of subcutaneous nodules, occasional digital gangrene, and histopathology aid in its diagnosis.

Atrophie Blanche

Porcelain white scars are seen in sickle cell disease, hydroxyurea ulcers, and malignant atrophic papulosis.

Other

Other close differentials are antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA)-associated vasculitis, cutaneous small-vessel vasculitis, cryoglobulinemia, and Sneddon syndrome (livedo racemosa with cerebrovascular stroke).[3][9][17][18][19]

Prognosis

The prognosis of livedoid vasculopathy may vary widely among patients. It is influenced by several factors, including the underlying cause, patients' treatment response, and associated conditions.

Key Considerations

Chronic course

Livedoid vasculopathy often follows a chronic and relapsing course. Episodes of painful ulcers and skin lesions may recur intermittently, and the condition may persist over an extended period.

Underlying causes

Identifying and addressing underlying causes or associated conditions is crucial for prognosis. Livedoid vasculopathy can be primary (idiopathic) or secondary to various conditions, such as hypercoagulable states, vasculitis, or connective tissue disorders. The prognosis may be better if the underlying cause is effectively managed.

Complications

The development of complications, such as nonhealing ulcers, skin atrophy, or secondary infections, can impact prognosis. Early and appropriate management of complications is essential to prevent long-term sequelae.

Response to treatment

The response to treatment can significantly influence prognosis. Therapeutic approaches for livedoid vasculopathy may include anticoagulants, immunosuppressive agents, and supportive wound care. Finding the most effective treatment regimen may sometimes require a trial-and-error approach.[20]

Multidisciplinary care

Collaboration between dermatologists, rheumatologists, hematologists, and other specialists is often necessary for comprehensive care. A multidisciplinary approach can contribute to a more thorough evaluation and management plan, potentially improving prognosis.

Complications

Livedoid vasculopathy mainly presents with ulcerative lesions in both lower limbs. Local complications like secondary skin infections that show typical signs of inflammation are commonly encountered. Other manifestations like pain (due to local hypoxic damage and cytokine reaction), secondary cutaneous hyperpigmentation (due to extravasation of erythrocytes along with hemosiderin deposition in the skin), and mononeuritis multiplex (due to thrombosis of vasa nervorum) and atrophic scarring of skin are seen.[1]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patient education is an important part of managing the disease. The patient should be educated about the importance of smoking cessation. Complying with the other general measures like compression stockings and wound care is also of utmost importance. Finally, the patient should be instructed about reporting urgently to the clinician in cases of worsening symptoms.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Livedoid vasculopathy is a challenging diagnosis. Surprisingly, the epidemiological data show a 5-year delay with adequate diagnosis and management of this condition. Therefore, an interprofessional team that includes nurses, primary clinicians, pharmacists, and dermatologists should be educated about identifying this condition. Many of the patients can be misdiagnosed. Hence, educating healthcare workers about identifying and performing routine workups before referring to the dermatologist is an important part of enhancing healthcare. Finally, the dermatologist should also know the importance of getting a skin biopsy of appropriate depth and dimensions to avoid missing the diagnosis.[1]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Freitas TQ, Halpern I, Criado PR. Livedoid vasculopathy: a compelling diagnosis. Autopsy & case reports. 2018 Jul-Sep:8(3):e2018034. doi: 10.4322/acr.2018.034. Epub 2018 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 30101138]

Goerge T. [Livedoid vasculopathy. Pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous infarction]. Der Hautarzt; Zeitschrift fur Dermatologie, Venerologie, und verwandte Gebiete. 2011 Aug:62(8):627-34; quiz 635. doi: 10.1007/s00105-011-2172-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21786003]

Alavi A, Hafner J, Dutz JP, Mayer D, Sibbald RG, Criado PR, Senet P, Callen JP, Phillips TJ, Romanelli M, Kirsner RS. Livedoid vasculopathy: an in-depth analysis using a modified Delphi approach. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2013 Dec:69(6):1033-1042.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.07.019. Epub 2013 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 24028907]

Eswaran H, Googe P, Vedak P, Marston WA, Moll S. Livedoid vasculopathy: A review with focus on terminology and pathogenesis. Vascular medicine (London, England). 2022 Dec:27(6):593-603. doi: 10.1177/1358863X221130380. Epub 2022 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 36285834]

Seguí M, Llamas-Velasco M. A comprehensive review on pathogenesis, associations, clinical findings, and treatment of livedoid vasculopathy. Frontiers in medicine. 2022:9():993515. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.993515. Epub 2022 Dec 8 [PubMed PMID: 36569162]

Bilgic A, Ozcobanoglu S, Bozca BC, Alpsoy E. Livedoid vasculopathy: A multidisciplinary clinical approach to diagnosis and management. International journal of women's dermatology. 2021 Dec:7(5Part A):588-599. doi: 10.1016/j.ijwd.2021.08.013. Epub 2021 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 35024414]

Coppola A, Davi G, De Stefano V, Mancini FP, Cerbone AM, Di Minno G. Homocysteine, coagulation, platelet function, and thrombosis. Seminars in thrombosis and hemostasis. 2000:26(3):243-54 [PubMed PMID: 11011842]

Shah SR, Vyas HR, Doshi YJ, Shah BJ. Clinical, Laboratory, Histopathological and Therapeutic Profile of Livedoid Vasculopathy: A Case Series of 17 Patients. Indian dermatology online journal. 2022 Nov-Dec:13(6):771-774. doi: 10.4103/idoj.idoj_182_22. Epub 2022 Oct 21 [PubMed PMID: 36386750]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHu SC, Chen GS, Lin CL, Cheng YC, Lin YS. Dermoscopic features of livedoid vasculopathy. Medicine. 2017 Mar:96(11):e6284. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000006284. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28296736]

Nuttawong S, Chularojanamontri L, Trakanwittayarak S, Pinkaew S, Chanchaemsri N, Rujitharanawong C. Direct immunofluorescence findings in livedoid vasculopathy: a 10-year study and literature review. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2021 Apr:46(3):525-531. doi: 10.1111/ced.14464. Epub 2020 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 32986882]

Gao Y, Jin H. Livedoid vasculopathy and its association with genetic variants: A systematic review. International wound journal. 2021 Oct:18(5):616-625. doi: 10.1111/iwj.13563. Epub 2021 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 33686673]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKumar A, Sharma A, Agarwal A. Livedoid vasculopathy presenting with leg ulcers. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2019 Nov 1:58(11):2076. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez126. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31220328]

Criado PR, Pagliari C, Morita TCAB, Marques GF, Pincelli TPH, Valente NYS, Garcia MSC, de Carvalho JF, Abdalla BMZ, Sotto MN. Livedoid vasculopathy in 75 Brazilian patients in a single-center institution: Clinical, histopathological and therapy evaluation. Dermatologic therapy. 2021 Mar:34(2):e14810. doi: 10.1111/dth.14810. Epub 2021 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 33496999]

Criado PR, Rivitti EA, Sotto MN, Valente NY, Aoki V, Carvalho JF, Vasconcellos C. Livedoid vasculopathy: an intringuing cutaneous disease. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2011 Sep-Oct:86(5):961-77 [PubMed PMID: 22147037]

Gao Y, Jin H. Efficacy of an anti-TNF-alpha agent in refractory livedoid vasculopathy: a retrospective analysis. The Journal of dermatological treatment. 2022 Feb:33(1):178-183. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2020.1737634. Epub 2020 Mar 9 [PubMed PMID: 32116074]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRustin MH, Bunker CB, Dowd PM. Chronic leg ulceration with livedoid vasculitis, and response to oral ketanserin. The British journal of dermatology. 1989 Jan:120(1):101-5 [PubMed PMID: 2638912]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: A review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2016 Sep-Oct:82(5):478-88. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.183635. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27297279]

Wu S, Xu Z, Liang H. Sneddon's syndrome: a comprehensive review of the literature. Orphanet journal of rare diseases. 2014 Dec 31:9():215. doi: 10.1186/s13023-014-0215-4. Epub 2014 Dec 31 [PubMed PMID: 25551694]

Mimouni D, Ng PP, Rencic A, Nikolskaia OV, Bernstein BD, Nousari HC. Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa in patients presenting with atrophie blanche. The British journal of dermatology. 2003 Apr:148(4):789-94 [PubMed PMID: 12752140]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRamphall S, Rijal S, Prakash V, Ekladios H, Mulayamkuzhiyil Saju J, Mandal N, Kham NI, Shahid R, Naik SS, Venugopal S. Comparative Efficacy of Rivaroxaban and Immunoglobulin Therapy in the Treatment of Livedoid Vasculopathy: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2022 Aug:14(8):e28485. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28485. Epub 2022 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 36051980]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence