Introduction

The lung veins sometimes referred to as the pulmonary veins, are blood vessels that transfer freshly oxygenated blood from the lungs to the left atria of the heart. They are the only veins in the adult human body, which contain a higher percentage of oxygenation of blood than their arterial counterpart, the pulmonary arteries.

These veins are part of the pulmonary circulatory system and are an important part of the respiratory system. The pulmonary veins can become distended in congestive heart failure (left-sided heart failure), resulting in pulmonary edema. Damage to the pulmonary veins epithelial lining can cause pleural effusions as well. However, pleural effusions have numerous etiologies such as infection, liver disease, or lymphatic dysfunction that should rank higher on a differential list than pulmonary vein damage.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The pulmonary veins originate from individual alveoli within the lung as capillary vessels. These capillary systems converge into larger veins called the interlobar pulmonary veins. An abnormality in the structure and development of these interlobar pulmonary veins results in primarily alveolar capillary dysplasia with misalignment of pulmonary veins.[1] This topic receives further discussion in the Clinical Significance section.

Further convergence of the interlobar pulmonary veins creates the subsegmental veins. The subsegmental veins may drain multiple segments of the same lobe of the lung. There is limited literature on the total drainage of lobe segments by numerous subsegmental veins. However, some evidence suggests that 33 to 55% of people have middle lung segments drained by one subsegmental vein. Another 45 to 67% of having a middle lung segment with two or more subsegmental veins.[2]

The subsegmental veins form a conflux into the pulmonary veins. The pulmonary veins also contain peripheral drainage from the deoxygenated blood bronchial veins.[3] There are four pulmonary veins. Pairs of two emerge from each of the hila of the lungs. The left superior pulmonary vein drains the left upper lobe and the lingula. The left inferior pulmonary vein drains the left lower lobe. The right superior pulmonary vein drains the right upper and middle lobe. The right inferior pulmonary vein drains the right lower lobe.

The superior pulmonary veins are anterior and caudal to the pulmonary arteries. The inferior pulmonary veins are inferior to the pulmonary arteries and are readily identifiable as the most inferior vessel on each hilum. Both left and right pulmonary ligaments are inferior and medial to the inferior pulmonary veins. The four pulmonary veins run medially to the left atria, where they drain into the left atrium through four distinct openings on the posterior wall.[3]

The anatomical relationship of the junction between the pulmonary veins and the epicardium of the left atrium is different depending on the person. We can find a plane of fibrous-adipose tissue between the adventitia of the veins and the epicardium. We can find a continuity of the epicardial tissue that invaginates in the adventitia of the vessels. Or, the epicardium can cover the vessel before entering the atrial cavity.

Embryology

The pulmonary veins begin development around two months of fetal gestation. Pouching of the dorsal wall of the dorsal mesocardium, which later develops into the left atria, gives rise to the common primitive pulmonary vein. During this time the common primitive pulmonary vein is still in connection to the systemic circulatory system. The primitive pulmonary vein then undergoes canalization into four independent and asymmetrical pulmonary veins, which connect the primitive intraparenchymal pulmonary network to the primitive left atria.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The pulmonary veins' function is to transport oxygenated blood from the lung alveoli into the left atria. Another set of veins also exist in the pulmonary system. The bronchial arteries and veins are the vessels responsible for delivering oxygen and carrying away carbon dioxide to the lung tissue itself. The right and left bronchial veins flow into the azygos and hemiazygos veins, respectively. There is slight variation in the network, and some bronchial veins may flow into the pulmonary veins. This drainage of the bronchial veins into the pulmonary veins results in a slightly diluted blood oxygen percentage level, somewhat less than the 100% that would be expected otherwise in the left atrium.[3][5]

Nerves

The pulmonary veins receive innervation from the pulmonary plexus. Parasympathetic and sympathetic motor nerve fibers control vasoconstriction and vasodilation, respectively. The parasympathetic portions of the pulmonary plexus derive from the vagus nerve. These nerves run anterior to the pulmonary bronchi and superior to the pulmonary veins. The sympathetic portion of the pulmonary plexus derives from the sympathetic trunk. These trunks run parallel to each other and lateral to the vertebral column. The sympathetic chain cuts medially into the hilum. This portion of the pulmonary plexus primarily runs posterior to the pulmonary bronchi. The pulmonary branch is the 1-4 ganglia group within the sympathetic trunk, at the level of T2-T5.[6]

Muscles

In the animal model, the tunica media of the pulmonary veins is constituted by cross-striated muscle tissue, which fibers are identical to the portion left atrial epicardial, posteriorly.

The atrium muscle fibers in the atrium venous junction have a non-linear orientation, probably to improve the junctional relationship with the different mechanical stimulations.

Physiologic Variants

The literature documents several physiologically normal patterns and variations. The normal pattern of four pulmonary veins, well-differentiated, and two from each side is present in 60 to 70% of the population.[3] Atypical but healthy variants are present in 30 to 38% of the population.[7] On the left side, there are two common variants. One common left-sided trunk that is considered either long or short variant. The short left common trunk variant is found in 15% of the population and is the most common variation of pulmonary vein anatomy. Right-sided variants tend to be more complex and rarer. The most common type of right-sided variance is a third accessory right pulmonary vein. These have multiple subgroups and classifications based on the relation of the accessory vein to the normal two pulmonary veins.[3]

Surgical Considerations

The pulmonary veins are extremely vascular. Any surgical procedure in the thorax should be careful not to damage them. There are several congenital conditions associated with left pulmonary malformation, as mentioned below. Most of these conditions require surgical correction if medical management has failed.[3]

The pulmonary veins merit consideration during any surgical procedure of the lung, such as a segmentectomy, lobectomy, or transplant. Indications for these interventions are commonly cystic fibrosis, tuberculosis, emphysema, benign tumor, or malignancy. Traditionally these procedures were done openly through a posterolateral thoracotomy approach. A relatively new minimally invasive technique in thoracic surgery, video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery, VATS, has shown to have a lower incidence of complications than classic open surgery.[8]

Clinical Significance

Pulmonary veins have clinical significance in two ways predominantly, congestion or anatomical malformation. Congestion occurs secondary to left-sided heart failure. Pulmonary edema that arises from pulmonary vein congestion gives rise to the respiratory symptoms with which most patients with congestive heart failure present.[9]

Anatomical malformation such as partial anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVR) and the more severe form, total anomalous pulmonary venous return (TAPVR).[10] The pulmonary venous malformation in PAPVR can present as an isolated finding or associated with other diseases, such as atrial septal defect (ASD) or scimitar syndrome.[11] The latter present with a classic triad of hypoplastic right lung, anomalous right pulmonary venous drainage to the IVC and anomalous systemic arterial supply to the right lower lobe. The name scimitar, derived from the curved anomalous venous drainage that resembles a Turkish sword on chest X-ray.[10] Another syndrome associated with PAPVR is Turner syndrome, 45 XO.[12] In TAPVR, all four of the pulmonary veins do not drain into the left atrium. Instead, they empty to the right atrium, causing cyanosis. Hence, it is one of the cyanotic congenital heart diseases. Based on the pulmonary veins drainage, it can subdivide into four types, supracardiac, infracardiac, cardiac, and mixed with the prevalence in descending order.[11] Historically, all forms of TAPVR needed surgical correction because of its grave prognosis (80% mortality in the first year of life).[13]

Another disease associated with abnormal veins is alveolar-capillary dysplasia with misaligned pulmonary veins (ACD/MPV). This rare and fatal disease (almost 100% mortality) is caused by unknown teratogen, which hinders the development of fetal lung vascularization. Significant decrease in alveolar capillary numbers causing the blood that enters individual lung unit to drain to this abnormal vein directly rather than from capillaries.[14]

To visualize the pulmonary veins, several radiographic modalities can be used, such as chest radiography, echocardiography, magnetic resonance imaging, and computed tomography (CT). Multidetector CT Scan is considered the best imaging modality for pulmonary veins evaluation.[3]

Agenesis of the right pulmonary veins is a very rare event. This condition involves the presence of collateral veins but less oxygenated blood.

Other Issues

In the presence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension, the pulmonary veins undergo a negative remodeling with increased fibrotic tissue in the intimal layer. The mechanism of vasorelaxation decreases in patients with COPD, with reduced levels of nitric oxide (NO) and endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF), both molecules that influence the tone of the vessel.

On an animal model with congestive heart failure (CHF), there would appear to be a sympathetic hyperinnervation of the vessels, with an increase in beta1-adrenergic receptors.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

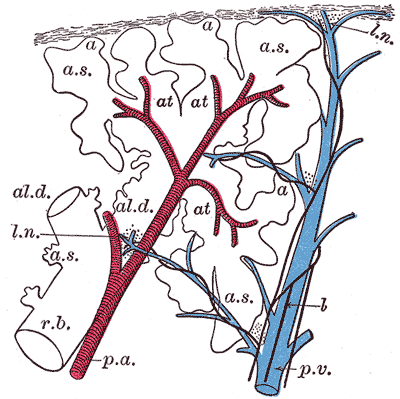

The Lungs. This image shows a schematic longitudinal section of a primary lobule of the lung.

r. b., respiratory bronchiole; al. d., alveolar duct; at., atria; a. s., alveolar sac; a, alveolus or air cell; p. a.: pulmonary artery: p. v., pulmonary vein; l., lymphatic; l. n., lymph node.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

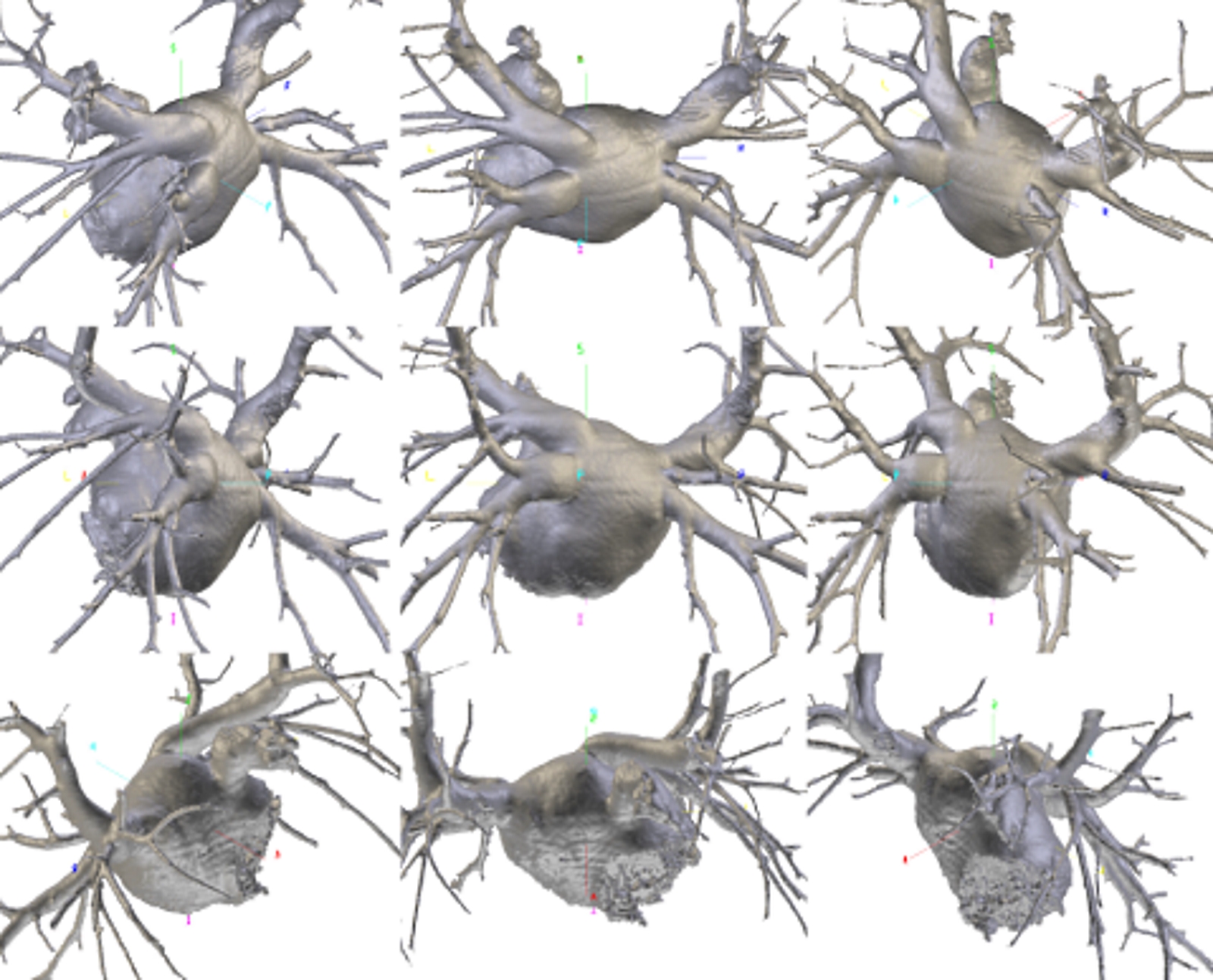

Multiplanar reconstructions with maximum intensity projection algorithm of the pulmonary veins and of the left atrium, on the oblique coronal plane. These reconstructions provide a more accurate assessment of the caliber, course and branching of the pulmonary veins. Lower right pulmonary vein with early branching (arrows of different colors). Contributed by Bruno Bordoni PhD

References

Antao B, Samuel M, Kiely E, Spitz L, Malone M. Congenital alveolar capillary dysplasia and associated gastrointestinal anomalies. Fetal and pediatric pathology. 2006 May-Jun:25(3):137-45 [PubMed PMID: 17060189]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRyba S, Topol M. Venous drainage of the middle lobe of the right lung in man. Folia morphologica. 2004 Aug:63(3):303-8 [PubMed PMID: 15478105]

Porres DV, Morenza OP, Pallisa E, Roque A, Andreu J, Martínez M. Learning from the pulmonary veins. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2013 Jul-Aug:33(4):999-1022. doi: 10.1148/rg.334125043. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23842969]

Webb S, Kanani M, Anderson RH, Richardson MK, Brown NA. Development of the human pulmonary vein and its incorporation in the morphologically left atrium. Cardiology in the young. 2001 Nov:11(6):632-42 [PubMed PMID: 11813915]

Marini TJ, He K, Hobbs SK, Kaproth-Joslin K. Pictorial review of the pulmonary vasculature: from arteries to veins. Insights into imaging. 2018 Dec:9(6):971-987. doi: 10.1007/s13244-018-0659-5. Epub 2018 Oct 31 [PubMed PMID: 30382495]

Belvisi MG. Overview of the innervation of the lung. Current opinion in pharmacology. 2002 Jun:2(3):211-5 [PubMed PMID: 12020459]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKato R, Lickfett L, Meininger G, Dickfeld T, Wu R, Juang G, Angkeow P, LaCorte J, Bluemke D, Berger R, Halperin HR, Calkins H. Pulmonary vein anatomy in patients undergoing catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: lessons learned by use of magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2003 Apr 22:107(15):2004-10 [PubMed PMID: 12681994]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDinic VD, Stojanovic MD, Markovic D, Cvetanovic V, Vukovic AZ, Jankovic RJ. Enhanced Recovery in Thoracic Surgery: A Review. Frontiers in medicine. 2018:5():14. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00014. Epub 2018 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 29459895]

Dupont M, Mullens W, Tang WH. Impact of systemic venous congestion in heart failure. Current heart failure reports. 2011 Dec:8(4):233-41. doi: 10.1007/s11897-011-0071-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21861070]

Dimas VV, Dillenbeck J, Josephs S. Congenital pulmonary vascular anomalies. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 2018 Jun:8(3):214-224. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2018.01.02. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30057871]

Najm HK, Williams WG, Coles JG, Rebeyka IM, Freedom RM. Scimitar syndrome: twenty years' experience and results of repair. The Journal of thoracic and cardiovascular surgery. 1996 Nov:112(5):1161-8; discussion 1168-9 [PubMed PMID: 8911312]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMoore JW, Kirby WC, Rogers WM, Poth MA. Partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage associated with 45,X Turner's syndrome. Pediatrics. 1990 Aug:86(2):273-6 [PubMed PMID: 2371102]

Shi G, Zhu Z, Chen J, Ou Y, Hong H, Nie Z, Zhang H, Liu X, Zheng J, Sun Q, Liu J, Chen H, Zhuang J. Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection: The Current Management Strategies in a Pediatric Cohort of 768 Patients. Circulation. 2017 Jan 3:135(1):48-58. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.023889. Epub 2016 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 27881562]

Bishop NB, Stankiewicz P, Steinhorn RH. Alveolar capillary dysplasia. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2011 Jul 15:184(2):172-9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1697CI. Epub 2011 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 21471096]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence