Introduction

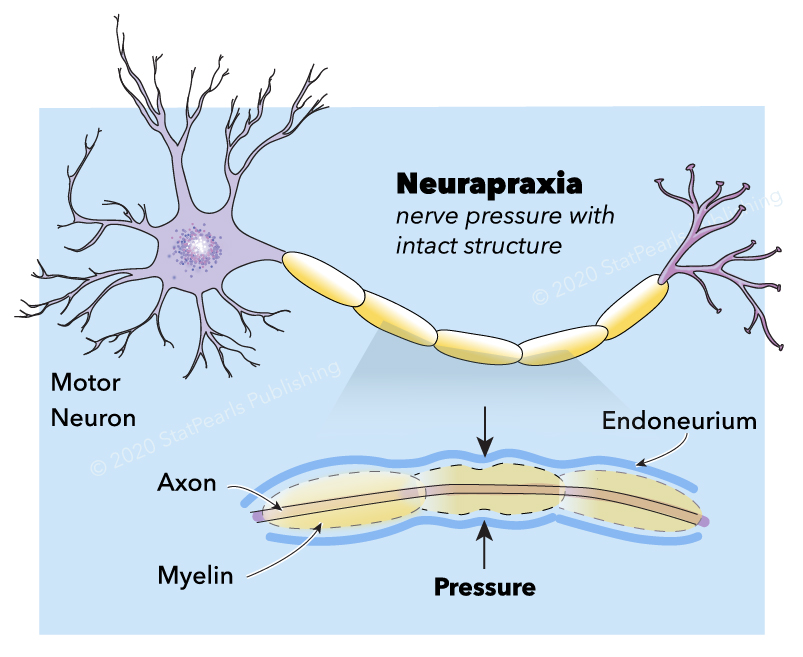

In 1942, Seddon classified the severity of peripheral nerve injury (PNI) in three types; neurapraxia, axonotmesis, or neurotmesis.[1][2] A few years later, in 1951, Sunderland classified them in five different degrees.[3] Neurapraxia is the mildest type of PNI commonly induced by focal demyelination or ischemia. It corresponds to grade 1 in Sunderland classification. In neurapraxia, the conduction of nerve impulses is blocked in the injured area. Motor and sensory conduction are partially or entirely lost. All the structures of the nerve stump, including the endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium, remain intact.

Neurapraxia occurs when the myelin sheath of the nerve is damaged. If the nerve is stimulated distal to the injured area, conduction is preserved. Neurapraxic injuries generally have a good prognosis. Spontaneous clinical and electrodiagnostic recovery of this type of injury is expected in three months when the nerve completes remyelination.

Frequently, the word neuropraxia is incorrectly used in the literature.[4][5] In the original 1942 classification by Seddon, neurapraxia was used; therefore, its correct use should continue in the scientific world.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Etiologies of neurapraxia are multiple.

- Bone fractures.

- Supracondylar fractures of the humerus, the incidence of 6-19%, the anterior interosseous branch of the median nerve, and ulnar nerve.[6][7]

- Improper positioning during anesthesia can affect ulnar, brachial, radial, common peroneal, sciatic, peroneal, great auricular nerves.[8][9]

- Transpsoas lumbar interbody fusion, obturator, or femoral neuropathy in 2.6%. Decreased quadriceps and iliopsoas strength.[10]

- Shoulder joint replacement, affecting the lateral cord of the brachial plexus, with the incidence of 20.9%. Caused by direct injury or excessive traction to the nerves during glenoid exposure.[11]

- Shoulder dislocation affecting the brachial plexus having an incidence of 5-55%.[12]

- ACDF: Intraoperative injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve by compression or traction.[13][14]

- Thyroidectomy: Intraoperative injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve in 1.5% of the patients producing hoarseness immediately after surgery due to unilateral vocal cord paralysis.[15]

- High impact sports causing brachial plexus neurapraxia, or "burners" and "stingers."[16][17][18][19] Occurs in 50-65% of football players. In rugby, injury occurs in 33.9%.[20]

- Biceps tendon repair affects the lateral antebrachial cutaneous nerve.[21][22]

- Postpartum.[23]

- Regional anesthesia produces injury in 1-2% of the patients.[24]

- During airway manipulation, damage to the lingual and greater palatine nerves.

- Park bench position affects the ulnar nerve, axillary nerve, and brachial plexus.

- Anterior cruciate ligament repair can cause injury to the superficial peroneal nerve.[25]

Transient neurological deficits can occur following interscalene brachial plexus block, axillary brachial plexus blocks, and femoral nerve blocks with an incidence of 2.84%, 1.48%, and 0.34%, respectively. Permanent neurological deficits will occur in only 0.04/1000 blocks.[24] Following ultrasound-guided nerve blocks, the incidence of transient neuropathies is 1.8/1000. Causes are mechanical by direct puncture of the nerve, pressure around the nerve, vascular/ischemic compromise by vasoconstriction, and inflammatory by scar.

Incorrect or careless patient positioning during anesthesia is an avoidable complication.[8] Ulnar nerve injury has an incidence of 1:215 to 1:385. The majority of ulnar nerve injuries occur in patients with pre-operative subclinical abnormalities of ulnar nerve conduction. During childbirth in the lithotomy position, the common peroneal nerve and the sciatic nerve can be injured due to nerve traction or compression. The radial nerve suffers injury due to compression between the humerus and the edge of the operating table. In the early postoperative period, patients complain of pain, paraesthesia, or weakness in the distribution of the nerve.

High-velocity trauma, lacerations, and penetrating injury usually produce axonotmesis or neurotmesis.

Epidemiology

The exact incidence and prevalence of neurapraxia are not clearly defined as it is usually combined with other types of PNI. The incidence of traumatic nerve injuries is approximately 350,000/year.[26][27][28] Traumatic nerve injuries occur more frequently in young adults, with an average age of 20 to 39.[29][30] Male sex is associated with 74% of traumatic injuries.[29][30] Neurapraxia injury may a similar incidence since most cases are secondary to traumatic injuries or high contact sports.

During the Iraq and Afghanistan war conflicts, 45% of the nerve injuries were due to neurapraxia of the ulnar, common peroneal, and tibial nerves.[31] In non-conflict time, mononeuropathies of the upper extremity are involved in 75% of the cases, commonly involving the ulnar nerve, alone or in combination.[30][32][33][34] Other reports consider the radial nerve as the most frequently involved, followed by the ulnar nerve, and then, the median nerve.[28] Combined lesions most commonly involved the ulnar and median nerves.[33][34] Penetrating injuries to the common peroneal nerve and sciatic nerve are the most frequent lesions in the lower extremity.[28][34][35]

The most common cause of PNI is vehicular accidents (46.4%), which affected mostly young men.[28][34] Other causes include penetrating trauma (23.9%), falls (10.9%), gunshot wounds (6.6%), pedestrians involved in car accidents (2.7%), sports-related (2.4%), and miscellaneous (7.2%).[34]

PNI has a prevalence ranging between 13 to 23 per 100,000 persons per year.[36][37]

Pathophysiology

Neural Anatomy: A nerve is composed of axons and connective tissue and the associated blood supply. Axons may be myelinated or unmyelinated. The endoneurium, perineurium, epineurium form the connective tissue to support the axons. The endoneurium surrounds each axon. Several axons are group together as a fascicle which is surrounded by the perineurium. The epineurium groups multiple fascicles. This last external connective tissue has an internal component (epifascicular) that encases the fascicles and an external component (epineural), which encases the entire nerve proper. External to the epineurium, there is a loose connective tissue called the mesoneurium or perineurium, which supports the nerve and contains the blood supply.[38]

Vascular Anatomy: The blood supply to the nerve is external to the epineurium. Extrinsic blood vessels join to form an anastomosing plexus of epineurial macro vessels. This anastomosing vasa nervorum penetrates the perineurium. Microvessels with non-fenestrated endothelium penetrate the endometrium and provide blood to axons.[38][39]

Neurapraxia is induced by focal demyelination or ischemia. All the structures of the nerve, including the endoneurium, perineurium, and epineurium, remain intact. The mechanism usually involves crush, traction, ischemia, and less common mechanisms such as thermal, electric shock, radiation, percussion, and vibration.[40] Increased pressure in a confined compartment (compartment syndrome), traction of the surrounding tissue, synovial tissue hypertrophy, tenosynovitis, hematoma, aneurysm, pseudoaneurysm, tissue edema, or local anesthetic injection proximal to the nerve can also produce neurapraxia.

Compression of a nerve can be acute or chronic. Compression at small openings and superficial nerve locations can damage the nerve and its blood supply. Scar tissue formation and inflammation can produce nerve entrapment.[41] During surgery, nerve injury occurs by focal compression or traction from the retractor. If a force is applied at a right angle to the nerve, compression occurs along the long axis of the nerve, resulting in a decrease of the diameter of the nerve. If the force is applied along the axis of the nerve, traction occurs, resulting in lengthening of the nerve.[42]

As a consequence of focal demyelination or ischemia, the nerve will have a decrease in conduction velocity and an increase in the latency. Compound muscle action potential (CMAP) amplitude evoked with stimulation above the injury is absent or markedly reduced, as compared with stimulation below the injury.[41] The CMAP amplitudes with stimulation below the injury usually remain normal or are only slightly reduced because it reflects the sum of all the motor unit potentials stimulated. Electromyography (EMG) does not show significant changes in neurapraxia, except for reduced MUP recruitment. Due to the myelin injury, motor nerves are affected more than sensory nerves, and weakness predominates.[16]

Neurapraxia had been studied in a rat model in which compression of 60 g/mm2 to the sciatic nerve produced a complete paralysis, which became normal in 14 days. An entire motor conduction block occurred if stimulated above the injured site, but below the compression site, remained normal. Wallerian degeneration signs were limited.[43]

History and Physical

Information regarding the mechanism of injury is essential as it will guide decisions about the management. The physical examination will point toward the specific nerve involved. The sensory and motor distribution of the nerve affected is tested.

Alteration in the nerve structure can produce motor impairment (weakness, hyporeflexia, and atrophy in chronic cases) and sensory impairment (pain, allodynia, hyperesthesia, hypoesthesia, paresthesia).[44] A combination of these is usually present, but motor deficits are more prominent. If there is a complete nerve injury, there will be anesthesia of the sensory distribution, and the muscles will show flaccid paralysis. If the damage is incomplete, some degree of preserved sensation or motion will be present. The presence of a Tinel sign indicates conduction along with the injured site.

Evaluation

Laboratory workup will include complete blood count, blood glucose, liver function, renal function, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, vitamin B12 levels, and thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Needle EMG is the most sensitive study. The motor response amplitude decrement begins around days 2–3 and is complete by day 6.[45] EMG is most useful 2 to 3 weeks after the injury as the involved muscles had undergone denervation. EMG is done every six weeks. Stimulation of the nerve below the lesion will result in a CMAP wave from the neurapraxic axons.[10] If there is an absence of CMAP upon stimulation, a complete injury had occurred, which has a poor prognosis. When small-amplitude, short-duration (SASD) motor unit potentials are detected, the prognosis for recovery is excellent.[10]

In a complete neurapraxia lesion, no motor unit action potentials (MUAPs) are elicited under voluntary control. EMG can differentiate if the cause of weakness is neuropathic or myopathic. In neurapraxic lesions, the muscle does not reveal any abnormal spontaneous activity (fibrillation and positive sharp waves). On follow-up, the presence of MUAPs indicates that reinnervation is taking place.[33]

In neurapraxia, CMAP and sensory nerve action potential (SNAP) can be elicited distal to the injury. Proximal to the injury, stimulation shows a partial or complete conduction block with varying degrees of decreased CMAP and SNAP associated with reduced conduction velocity. Remyelination improves the changes partially or entirely. Electrodiagnostic studies done two weeks after the injury will show CMAP and SNAP with distal stimulation and will differentiate from a neurotmesis or axonotmesis injury.[33]

Ultrasound can help to identify the continuity of the nerve and exclude neurotmesis injuries.[38]

A computed tomographic scan of the affected area can be helpful to show unreduced fractures causing compression or misplaced hardware.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the lumbar spine and pelvis should be done immediately in traumatic and post-operative cases presenting deficits to rule out a compressive source of neuropathy. Diffusion tensor tractography with three-dimensional maps of fiber tracts showing the nerve fiber bundles within the tissue can be obtained using diffusion-weighted imaging and diffusion tensor imaging.[23][45][46]

Treatment / Management

For neurapraxic injuries, conservative treatment is recommended. This includes orthotic measures with splints and limb supports, physical rehabilitation, avoidance of the aggravating activity, and neuropathic pain medications (analgesics, antidepressants, anticonvulsants, corticosteroids, anesthetics). Serial examinations and electrodiagnostic studies are performed to assess for evidence of improvement.[16][45]

If there is compression by a hematoma, urgent surgical decompression is performed. If it is due to a fracture, surgical decompression may be required. In compartment syndrome, fasciotomy is needed.

If there is no clinical and electrophysiological recovery after 3–6 months, surgical intervention can be required as scar tissue may be preventing improvement. The nerve can have a simple decompression or a decompression with transposition.

Rehabilitation should include psychological support and pain control.[47] Pain control is challenging in PNI. Nerve injury produces a characteristic burning sensation and dysesthesias along with the nerve distribution. Tricyclic antidepressants, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, anticonvulsants (carbamazepine, phenytoin, lamotrigine, gabapentin, and pregabalin), and baclofen can be used. For short-term use, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, tramadol, and opioids can be used.[33](B3)

Prevention should be emphasized, especially for iatrogenic damage.[47] Repeat injury should be prevented. Persistent compression can result in a delayed recovery or full recovery.

Differential Diagnosis

Neurapraxia resembles many other nerve and muscle illnesses; therefore, the following differentials should be kept in mind when assessing such patients.

- Neurotmesis

- Axonotmesis

- Metabolic (Diabetic neuropathy)

- Inflammatory neuritis

- Infectious neuropathy (HIV, leprosy)

- Paraneoplastic neuropathy

- Hypothyroidism

- Alcohol

- Malnutrition

- Radiculopathy

- Myelopathy

- Spinal cord trauma

- Spinal cord infarction

- Muscle diseases

- Upper neuron disease

Prognosis

Neurapraxia has an excellent prognosis. It is a non-axonal injury, and most patients experience recovery within 2–3 months.[42] Young age favors a better functional outcome, but permanent disability can occur in up to 30% of cases.[48] Those with profound injuries can have long, sick-leave periods.

For ulnar nerve injury, patients should be informed that half of the cases recover within six weeks; however, the remaining half can still be impaired at two years.[49] Brachial plexus injuries after improper positioning during general anesthesia had a full recovery in 82% of the cases.

Half of the sport-related neurapraxic injuries resulted in < 1-week time loss, but in 9.4%, the athletes will lose their season.[18] In an athlete, a PNI can affect his safe return to play.[16]

Complications

Neurapraxia, apart from medical complications, had a considerable impact on the life of the individual. The following are a few complications of neurapraxia.

- Neuropathic pain

- Psychological issues

- Economic losses

- Muscle atrophy if incorrectly diagnosed

Consultations

Evaluation and management of neurapraxia is a multidisciplinary approach. Following specialties while working in collaboration can improve outcomes in these patients.

- Neurosurgeon

- Neurologist

- Physiatrist

- Electrophysiological technologist

- Ultrasound technologist

Deterrence and Patient Education

Prevention is the initial step in dealing with neurapraxia. Rehabilitation of these injuries will significantly impact the wellbeing of patients and improve the management of this condition to improve outcomes. Patients must be educated and counseled to seek medical attention as soon as possible to evaluate for treatable causes. Patients can have several weeks of no return of sensory or motor functions, but they should be encouraged to maintain physical therapy and rehabilitation sessions. In approximately three months, the nerve should have recovered.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Neurapraxia frequently poses a diagnostic dilemma and should be differentiated from axonotmesis or neurotmesis. The causes of neurapraxia are many, but the prognosis is usually excellent.

While the neurosurgeon is almost always involved in the care of patients presenting with neurapraxia, it is essential to consult with an interprofessional team of specialists that include a physiatrist and the rehabilitation team. The physiatrist will evaluate the patient and do the appropriate electrodiagnostic studies to enhance and restore functional ability and quality of life to the patient with physical impairments. Physical therapists will help patients in rehabilitation. Prompt consultation with an interprofessional group of specialists is recommended to improve outcomes. Periodic clinical and electrodiagnosis exams are recommended to evaluate for the improvement of nerve function.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Seddon HJ. A Classification of Nerve Injuries. British medical journal. 1942 Aug 29:2(4260):237-9 [PubMed PMID: 20784403]

Kaya Y, Sarikcioglu L. Sir Herbert Seddon (1903-1977) and his classification scheme for peripheral nerve injury. Child's nervous system : ChNS : official journal of the International Society for Pediatric Neurosurgery. 2015 Feb:31(2):177-80. doi: 10.1007/s00381-014-2560-y. Epub 2014 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 25269543]

SUNDERLAND S. A classification of peripheral nerve injuries producing loss of function. Brain : a journal of neurology. 1951 Dec:74(4):491-516 [PubMed PMID: 14895767]

Huntley JS. Neurapraxia and not neuropraxia. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2014 Mar:67(3):430-1. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.09.031. Epub 2013 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 24120417]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBennett RG. Neurapraxia Not Neuropraxia. Dermatologic surgery : official publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et al.]. 2018 Apr:44(4):603-604. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001485. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29419544]

Vaquero-Picado A, González-Morán G, Moraleda L. Management of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. EFORT open reviews. 2018 Oct:3(10):526-540. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.3.170049. Epub 2018 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 30662761]

Babal JC, Mehlman CT, Klein G. Nerve injuries associated with pediatric supracondylar humeral fractures: a meta-analysis. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2010 Apr-May:30(3):253-63. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0b013e3181d213a6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20357592]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHewson DW, Bedforth NM, Hardman JG. Peripheral nerve injury arising in anaesthesia practice. Anaesthesia. 2018 Jan:73 Suppl 1():51-60. doi: 10.1111/anae.14140. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29313904]

Joshi M, Cheng R, Kamath H, Yarmush J. Great auricular neuropraxia with beach chair position. Local and regional anesthesia. 2017:10():75-77. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S138998. Epub 2017 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 28790863]

Abel NA, Januszewski J, Vivas AC, Uribe JS. Femoral nerve and lumbar plexus injury after minimally invasive lateral retroperitoneal transpsoas approach: electrodiagnostic prognostic indicators and a roadmap to recovery. Neurosurgical review. 2018 Apr:41(2):457-464. doi: 10.1007/s10143-017-0863-7. Epub 2017 May 30 [PubMed PMID: 28560607]

Ball CM. Neurologic complications of shoulder joint replacement. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2017 Dec:26(12):2125-2132. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.04.016. Epub 2017 Jul 5 [PubMed PMID: 28688932]

Gutkowska O, Martynkiewicz J, Urban M, Gosk J. Brachial plexus injury after shoulder dislocation: a literature review. Neurosurgical review. 2020 Apr:43(2):407-423. doi: 10.1007/s10143-018-1001-x. Epub 2018 Jun 30 [PubMed PMID: 29961154]

Yerneni K, Burke JF, Nichols N, Tan LA. Delayed Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve Palsy Following Anterior Cervical Discectomy and Fusion. World neurosurgery. 2019 Feb:122():380-383. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.11.066. Epub 2018 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 30465958]

Evman MD, Selcuk AA. Vocal Cord Paralysis as a Complication of Endotracheal Intubation. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2020 Mar/Apr:31(2):e119-e120. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000005959. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31985591]

Serpell JW, Lee JC, Yeung MJ, Grodski S, Johnson W, Bailey M. Differential recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy rates after thyroidectomy. Surgery. 2014 Nov:156(5):1157-66. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2014.07.018. Epub 2014 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 25444315]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLolis AM, Falsone S, Beric A. Common peripheral nerve injuries in sport: diagnosis and management. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2018:158():401-419. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63954-7.00038-0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30482369]

Hartley RA, Kordecki ME. REHABILITATION OF CHRONIC BRACHIAL PLEXUS NEUROPRAXIA AND LOSS OF CERVICAL EXTENSION IN A HIGH SCHOOL FOOTBALL PLAYER: A CASE REPORT. International journal of sports physical therapy. 2018 Dec:13(6):1061-1072 [PubMed PMID: 30534471]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZuckerman SL, Kerr ZY, Pierpoint L, Kirby P, Than KD, Wilson TJ. An 11-year analysis of peripheral nerve injuries in high school sports. The Physician and sportsmedicine. 2019 May:47(2):167-173. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2018.1544453. Epub 2018 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 30392428]

Feinberg JH. Burners and stingers. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America. 2000 Nov:11(4):771-84 [PubMed PMID: 11092018]

Kawasaki T, Ota C, Yoneda T, Maki N, Urayama S, Nagao M, Nagayama M, Kaketa T, Takazawa Y, Kaneko K. Incidence of Stingers in Young Rugby Players. The American journal of sports medicine. 2015 Nov:43(11):2809-15. doi: 10.1177/0363546515597678. Epub 2015 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 26337244]

Beks RB, Claessen FM, Oh LS, Ring D, Chen NC. Factors associated with adverse events after distal biceps tendon repair or reconstruction. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2016 Aug:25(8):1229-34. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.02.032. Epub 2016 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 27107731]

Watson JN, Moretti VM, Schwindel L, Hutchinson MR. Repair techniques for acute distal biceps tendon ruptures: a systematic review. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2014 Dec 17:96(24):2086-90. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.M.00481. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25520343]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYoo Y, Kim SJ, Oh J. Postpartum sciatic neuropathy: Segmental fractional anisotropy analysis to disclose neurapraxia. Neurology. 2016 Aug 30:87(9):954-5. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003051. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27572428]

Brull R, McCartney CJ, Chan VW, El-Beheiry H. Neurological complications after regional anesthesia: contemporary estimates of risk. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2007 Apr:104(4):965-74 [PubMed PMID: 17377115]

Alrowaili M. Transient Superficial Peroneal Nerve Palsy After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. Clinics and practice. 2016 Apr 26:6(2):832. doi: 10.4081/cp.2016.832. Epub 2016 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 27478579]

Fowler JR, Lavasani M, Huard J, Goitz RJ. Biologic strategies to improve nerve regeneration after peripheral nerve repair. Journal of reconstructive microsurgery. 2015 May:31(4):243-8. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1394091. Epub 2014 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 25503421]

Castillo-Galván ML, Martínez-Ruiz FM, de la Garza-Castro O, Elizondo-Omaña RE, Guzmán-López S. [Study of peripheral nerve injury in trauma patients]. Gaceta medica de Mexico. 2014 Nov-Dec:150(6):527-32 [PubMed PMID: 25375283]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNoble J, Munro CA, Prasad VS, Midha R. Analysis of upper and lower extremity peripheral nerve injuries in a population of patients with multiple injuries. The Journal of trauma. 1998 Jul:45(1):116-22 [PubMed PMID: 9680023]

Bekelis K, Missios S, Spinner RJ. Falls and peripheral nerve injuries: an age-dependent relationship. Journal of neurosurgery. 2015 Nov:123(5):1223-9. doi: 10.3171/2014.11.JNS142111. Epub 2015 May 15 [PubMed PMID: 25978715]

Kouyoumdjian JA. Peripheral nerve injuries: a retrospective survey of 456 cases. Muscle & nerve. 2006 Dec:34(6):785-8 [PubMed PMID: 16881066]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBirch R, Misra P, Stewart MP, Eardley WG, Ramasamy A, Brown K, Shenoy R, Anand P, Clasper J, Dunn R, Etherington J. Nerve injuries sustained during warfare: part I--Epidemiology. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 2012 Apr:94(4):523-8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B4.28483. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22434470]

Siemionow M, Brzezicki G. Chapter 8: Current techniques and concepts in peripheral nerve repair. International review of neurobiology. 2009:87():141-72. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(09)87008-6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19682637]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCampbell WW. Evaluation and management of peripheral nerve injury. Clinical neurophysiology : official journal of the International Federation of Clinical Neurophysiology. 2008 Sep:119(9):1951-65. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2008.03.018. Epub 2008 May 14 [PubMed PMID: 18482862]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKouyoumdjian JA, Graça CR, Ferreira VFM. Peripheral nerve injuries: A retrospective survey of 1124 cases. Neurology India. 2017 May-Jun:65(3):551-555. doi: 10.4103/neuroindia.NI_987_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28488619]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGosk J, Rutowski R. Penetrating injuries to the nerves of the lower extremity: principles of diagnosis and treatment. Ortopedia, traumatologia, rehabilitacja. 2005 Dec 30:7(6):651-5 [PubMed PMID: 17611430]

Sullivan R, Dailey T, Duncan K, Abel N, Borlongan CV. Peripheral Nerve Injury: Stem Cell Therapy and Peripheral Nerve Transfer. International journal of molecular sciences. 2016 Dec 14:17(12): [PubMed PMID: 27983642]

Muheremu A, Ao Q. Past, Present, and Future of Nerve Conduits in the Treatment of Peripheral Nerve Injury. BioMed research international. 2015:2015():237507. doi: 10.1155/2015/237507. Epub 2015 Sep 27 [PubMed PMID: 26491662]

Biso GMNR, Munakomi S. Neuroanatomy, Neurapraxia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491678]

Mizisin AP, Weerasuriya A. Homeostatic regulation of the endoneurial microenvironment during development, aging and in response to trauma, disease and toxic insult. Acta neuropathologica. 2011 Mar:121(3):291-312. doi: 10.1007/s00401-010-0783-x. Epub 2010 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 21136068]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOmejec G, Podnar S. Contribution of ultrasonography in evaluating traumatic lesions of the peripheral nerves. Neurophysiologie clinique = Clinical neurophysiology. 2020 Apr:50(2):93-101. doi: 10.1016/j.neucli.2020.01.007. Epub 2020 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 32089405]

Pietraszek PM. Regional anaesthesia induced peripheral nerve injury. Anaesthesiology intensive therapy. 2018:50(5):367-377. doi: 10.5603/AIT.2018.0049. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30615796]

Sunderland S. The anatomy and physiology of nerve injury. Muscle & nerve. 1990 Sep:13(9):771-84 [PubMed PMID: 2233864]

Omura T, Sano M, Omura K, Hasegawa T, Nagano A. A mild acute compression induces neurapraxia in rat sciatic nerve. The International journal of neuroscience. 2004 Dec:114(12):1561-72 [PubMed PMID: 15512839]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRadić B, Radić P, Duraković D. PERIPHERAL NERVE INJURY IN SPORTS. Acta clinica Croatica. 2018 Sep:57(3):561-569. doi: 10.20471/acc.2018.57.03.20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31168190]

Ferrante MA. The Assessment and Management of Peripheral Nerve Trauma. Current treatment options in neurology. 2018 Jun 1:20(7):25. doi: 10.1007/s11940-018-0507-4. Epub 2018 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 29855741]

Marquez Neto OR, Leite MS, Freitas T, Mendelovitz P, Villela EA, Kessler IM. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of peripheral nerves following traumatic lesion: where do we stand? Acta neurochirurgica. 2017 Feb:159(2):281-290. doi: 10.1007/s00701-016-3055-2. Epub 2016 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 27999953]

Kumar A, Shukla D, Bhat DI, Devi BI. Iatrogenic peripheral nerve injuries. Neurology India. 2019 Jan-Feb:67(Supplement):S135-S139. doi: 10.4103/0028-3886.250700. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30688247]

Bergmeister KD, Große-Hartlage L, Daeschler SC, Rhodius P, Böcker A, Beyersdorff M, Kern AO, Kneser U, Harhaus L. Acute and long-term costs of 268 peripheral nerve injuries in the upper extremity. PloS one. 2020:15(4):e0229530. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229530. Epub 2020 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 32251479]

Warner MA, Warner DO, Matsumoto JY, Harper CM, Schroeder DR, Maxson PM. Ulnar neuropathy in surgical patients. Anesthesiology. 1999 Jan:90(1):54-9 [PubMed PMID: 9915312]