Introduction

Triage is the sorting and categorizing of patients based on clinical severity to maximize the results for most patients when limited resources are available. It is a tried and true method used in multiple scenarios in multiple practice environments worldwide. Most are familiar with the triage process upon initial arrival of patients to a medical facility or upon arrival at the scene when there are multiple casualties. Triage in these situations involves using the START method or similar clinically based tool tailored to the individual practice environment, such as emergency departments, and refined during training events, as discussed in separate topics. Triage, however, does not stop after the first iteration. It must be continually used and reevaluated during any transition of care or when resources or situations change.

Patients who arrive at a treatment area undergo triage, as discussed above. This topic covers the triage process before moving patients out from 1 area of care to another. This is done to prioritize which patients are to be moved first and determine by what means they are transported based on available resources, patients' acuity, and treatments or monitoring needed en route; hence, the term "evacuation triage."

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Just as patients undergo triage when entering a medical treatment area, triage of patients is necessary before transferring them to other treatment areas or different facilities. The same principles necessitating triage upon arrival drive essential components of evacuation triage. When the needs outstrip resources, triage must be utilized to maximize the results for the number of patients. There are unique characteristics of evacuation triage that separate it from its counterpart, though that must be discussed and well understood before implementation.

The first key difference is to understand that providers are not triaging patients to prioritize treatments. Instead, they are triaging to prioritize evacuation. Recognizing that the patients are already in a treatment area and receiving medical care is essential. The reasons that would necessitate evacuation include being transferred to receive definitive care, going to a higher level of care with further resources or sub-specialization, or clearing space at the forward treatment area to make room for new patients.

The other significant difference is in recognizing into what categories to triage patients. Evacuation triage does not follow the medical triage designations such as 1-5 of the Emergency Severity Index or the color-coded Red Yellow Green Black methodology of (Jump) START.[1] These emphasize how quickly patients need to be seen, reexamined, or have an intervention. Instead, patients are sorted into categories designating prioritized timelines for evacuation. The US military and NATO partners have utilized this method for several decades. There are variations on the theme, and updates to the tools have occurred over the years, but it essentially boils down to “How quickly do we need to move this patient from their current location to the next?”

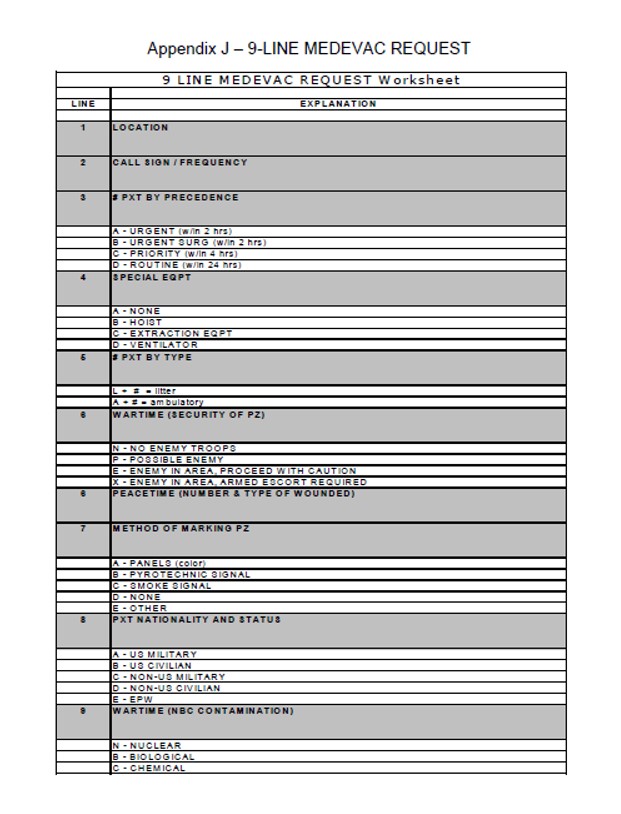

The 9 Line Medevac of the military is the report and request for resources used once it is determined there is a need to evacuate patients. It has several essential pieces of information that we discuss further but which merit consideration in all evacuation cases. Other pieces of information do not apply to most civilian situations but highlight that there are often other factors in even the most routine evacuation that should be accounted for before execution (See Image. 9-Line MEDEVAC Request).

The first portion of evacuation triage is to recognize how many patients there are to move and by what means they need transport. Can the patients walk and move on their own? Are they on a backboard? Are they bed-bound? These questions help determine what type of vehicle they fit into and if personnel is needed to help move them.

The next step in evacuation triage is recognizing how quickly each patient needs removal from the current treatment area. Patients may be sick, but as long as they receive care at the current level, they may be stable enough to hold off evacuation while other patients who cannot be maintained in the current treatment area obtain transport.

Next, there needs to be synchronization regarding which patient requires removal. What resources are necessary en route? Do patients require ventilators? Do they require medicine pumps? Is special equipment required to move or extricate the patient?

Understanding all resources available is essential to this portion of evacuation triage. Medical evacuation assets, including ambulances and helicopters, may be available for normal use in evacuation plans. These assets should be well known and hopefully rehearsed in their employment by those utilizing them to manage evacuations. In a triage scenario, these resources are likely overwhelmed or insufficient to handle the volume of patients that need evacuation during a specific period.

The use of casualty evacuation, discussed in different topics, may be necessary and the most appropriate use of resources. Nonstandard evacuation methods can help facilitate the quick movement of many patients; all patients should be matched to a specific resource. Those requiring medical treatment en route should be prioritized for the medical evacuation vehicles. In contrast, those stable enough to be transported by casualty evacuation can utilize nonstandard forms, as discussed.

Each evacuation resource has an intrinsic number of patients they can move depending on the severity and resources required. For instance, patients who can sit upright take up less space in a ground vehicle, and more may be transportable in 1 trip. Patients are generally unable to sit in air ambulances, and air ambulances have inherent limitations on the number of patients they can carry. Their use in evacuation triage must prioritize those requiring the most care in route for the most expedient evacuation.

A detailed understanding of the current situation and the environment, along with broad situational awareness, is essential to maintain the flow of patients through the evacuation process. Below is a basic flow that one can use to help visualize the evacuation process and be aware of where triage is often necessary to help those managing the scene ensure that they are aware of potential bottlenecks and can develop workarounds to improve flow.

- Phase 1 – Patients undergo identification in the field. They receive point-of-care treatment. They can then evacuate to a casualty collection point.

- Phase 2 – CCPs are the first receiving points for groups of patients. They are triaged on arrival and receive further care. CCPs are often temporary and hastily assembled in a disaster. Patients need a transfer for more definitive care.

- Phase 3 – Patients undergo triage for evacuation to a higher level of care. Further planning and resources should begin in this phase. While casualty evacuation was likely all that was available at the point of injury, medical evacuation assets can begin to be utilized and appropriated into the plan.

- Phase 4 – Multiple inflection points should be utilized during an evacuation to maximize turnaround times. Exchange points and asset release triggers are some of the most common.

- Phase 5 – After arriving at a higher level of care, patients undergo another triage process for evaluation and treatment. After stabilization, some patients may require additional evacuation, cycling back to Phase 3.

Clinical Significance

Once the need to evacuate is determined, planning for its implementation must begin in earnest. Ideally, plans have been prepared and rehearsed, but every scenario is different and may not proceed as expected. The ability to adapt to the current situation is vital. Having a rehearsed plan, regardless of its fidelity to real-life conditions, sets a baseline from which all providers can branch out.[2]

As seen in the evacuation phases, there are multiple transitions of care along with the periods of evacuation. If 1 of the legs of evacuation is known to be a prolonged process, it may become necessary to establish exchange points along the route of evacuation. Ambulance exchange points can work in 2 general ways. First, 1 evacuation asset moves to an established location and transfers its patients to another waiting evacuation asset before returning to the pickup point. This method may be most useful in situations such as HAZMAT contamination.[3] The "dirty" ambulance can drop off patients at a decontamination site before further evacuation and then return to the scene faster. It is perhaps most commonly used when there is a need for air ambulance evacuation but no suitable helicopter landing zone is nearby. An ambulance may drive to the point that the helicopter can land, exchange patients, and then return to the pickup point of the original scene.[4] Another way to utilize ambulance exchange points is to have evacuation assets that employ release triggers. An asset waits at 1 location and then is triggered to go to the pickup point by either a call for further resources or with known events, such as being passed by 1 ambulance in the evacuation process. That site can serve as a staging point for evacuation assets without physically exchanging patients.

The 9 Line Medevac report shows multiple issues may affect an evacuation. Communication between sites and moving assets is essential. Appropriate backup communication methods should be part of the plan, including being told to go to a designated staging area and awaiting further instructions. The routes that assets take should be known. It is not inconceivable that 1 route becomes unusable after an evacuation chain has been used. If there is a backlog on 1 route, prioritizing routes for the highest triaged patients may also become necessary. Various safety issues such as terrain, weather, contamination, or violence may need to be anticipated, and a balance between the need to evacuate and not should always merit consideration.

When utilizing evacuation triage, consideration of all these factors is crucial, and incorporation during the execution of the plan established on the scene is vital. It is incumbent on the scene or incident commander to take charge of the evacuation chain or delegate this role to an appropriate party with authority and situational awareness. When executed properly, evacuation triage moves patients to appropriate treatment centers in a safe and timely fashion and ultimately helps to save resources and lives.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ferrandini Price M, Arcos González P, Pardo Ríos M, Nieto Fernández-Pacheco A, Cuartas Álvarez T, Castro Delgado R. Comparison of the Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment system versus the Prehospital Advanced Triage Model in multiple-casualty events. Emergencias : revista de la Sociedad Espanola de Medicina de Emergencias. 2018 Ago:30(4):224-230 [PubMed PMID: 30033695]

Born C, Mamczak C, Pagenkopf E, McAndrew M, Richardson M, Teague D, Wolinsky P, Monchik K. Disaster Management Response Guidelines for Departments of Orthopaedic Surgery. JBJS reviews. 2016 Jan 5:4(1):. pii: e1. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.O.00026. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27490004]

Cibulsky SM, Sokolowski D, Lafontaine M, Gagnon C, Blain PG, Russell D, Kreppel H, Biederbick W, Shimazu T, Kondo H, Saito T, Jourdain JR, Paquet F, Li C, Akashi M, Tatsuzaki H, Prosser L. Mass Casualty Decontamination in a Chemical or Radiological/Nuclear Incident with External Contamination: Guiding Principles and Research Needs. PLoS currents. 2015 Nov 2:7():. pii: ecurrents.dis.9489f4c319d9105dd0f1435ca182eaa9. doi: 10.1371/currents.dis.9489f4c319d9105dd0f1435ca182eaa9. Epub 2015 Nov 2 [PubMed PMID: 26635995]

Loyd JW, Larsen T, Kuhl EA, Swanson D. Aeromedical Transport. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30085528]

Bazyar J, Farrokhi M, Khankeh H. Triage Systems in Mass Casualty Incidents and Disasters: A Review Study with A Worldwide Approach. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences. 2019 Feb 15:7(3):482-494. doi: 10.3889/oamjms.2019.119. Epub 2019 Feb 12 [PubMed PMID: 30834023]