Introduction

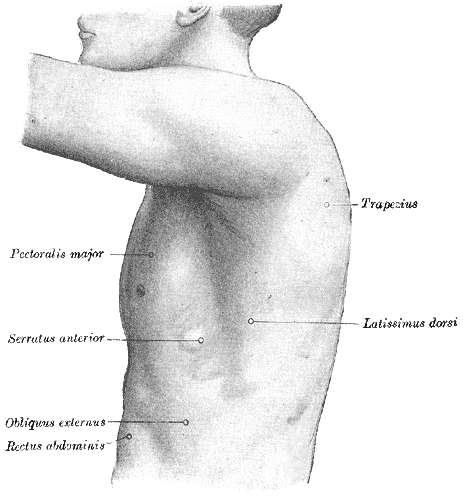

The serratus anterior is a fan-shaped muscle that originates on the superolateral surfaces of the first to eighth ribs or the first to ninth ribs at the lateral wall of the thorax and inserts along the superior angle, medial border, and inferior angle of the scapula. The main part of the serratus anterior lies deep to the scapula and the pectoral muscles and is easily palpated between the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi muscles. This large muscle is generally divided into three distinct parts according to the points of insertion: serratus anterior superior (insertion near the superior angle), serratus anterior intermediate (insertion along the medial border), and serratus anterior inferior (insertion near the inferior angle).[1] See Image. External Abdominal Muscles.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The serratus anterior muscle pulls the scapula forward around the thorax, which allows for anteversion and protraction of the arm (see Image. Surface Anatomy of the Thorax). Although this motion is antagonistic to that of the rhomboids when the serratus anterior superior and the serratus anterior inferior act together, the scapula is subsequently pressed against the thorax in conjunction with the rhomboids, thereby creating a synergistic effect. Also, the serratus anterior inferior is responsible for the anterolateral motion of the scapula, which allows for arm elevation. When the shoulder girdle is fixed, all three parts of the serratus anterior muscle work together to lift the ribs, assisting with respiration. The serratus anterior, also known as the “boxer’s muscle,” is largely responsible for the protraction of the scapula, a movement that occurs when throwing a punch. Furthermore, the serratus anterior acts with the upper and lower fibers of the trapezius muscle to sustain upward rotation of the scapula, which allows for overhead lifting.

Embryology

The exact origin of the tissue, which gives rise to the serratus anterior, is uncertain. In the 9 mm embryo, the serratus anterior begins to differentiate from the mesenchyme located at the ventral ends of the lower cervical myotomes. At this point, the pre-muscle mass is a continuous column with no defined attachments to the vertebrae or ribs over which it extends. In the 11 mm embryo, the muscle mass that will become the serratus anterior is a well-defined muscular column from the cervical region to the thorax. The thoracic portion, which eventually differentiates into the future serratus anterior muscle, gradually becomes more slender in the caudal region and forms distinct digitations to the upper nine ribs. At this stage, while attachments to the cervical vertebrae have formed, the serratus anterior has not attached itself to the scapula. In the 14 mm embryo, the serratus anterior begins to resemble the adult form, differentiating into a broad and flat muscle that attaches to the scapula.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The vascular supply to the serratus anterior includes the lateral thoracic artery, the superior thoracic artery, and the thoracodorsal artery. The lateral thoracic artery, also known as the external mammary artery, originates from the axillary artery and courses along the lower margin of the pectoralis minor muscle and supplies oxygenated blood to the serratus anterior muscle and pectoralis major muscle. Branches travel across the axilla to the axillary lymph nodes and subscapularis muscle. The superior thoracic artery is typically the first division of the axillary artery but may arise from the thoracoacromial artery. The superior thoracic supplies the superior part of the serratus anterior as well as the first and second intercostal spaces. The thoracodorsal artery supplies the lower portion of the serratus anterior and the latissimus dorsi.[3]

Nerves

The long thoracic nerve, which originates from the upper portion of the superior trunk of the brachial plexus and is typically composed of cervical nerves C5, C6, and C7, is responsible for the innervation of the serratus anterior. The long thoracic nerve courses inferiorly on the surface of the serratus anterior and, as such, is susceptible to damage during specific surgical procedures, especially with axillary lymph node dissection. The nerve’s relatively smaller diameter compared to other nerves of the brachial plexus, its minimal connective tissue, and superficial course over the surface of the serratus anterior muscle leads to greater exposure along its course. Injury to the long thoracic nerve may be due to other non-surgical causes, including nerve compression by the middle scalene muscle, second rib, or fascial sheath; entrapment within the middle or posterior scalene muscles; and traction on the nerve itself.[4][5][6] If the long thoracic nerve is damaged, a clinical phenomenon known as a winged scapula occurs as the serratus anterior is no longer able to hold the scapula against the chest wall. The winging is medial scapula winging that has to be differentiated from lateral winging due to a weakness of the rhomboids or the trapezius muscles.

Innervation of the serratus anterior differs depending on the part of the muscle, which suggests that the superior part may be intimately related to the levator scapulae, while the middle and inferior segments may serve as the true serratus anterior muscle.[1] The superior part has 2 different sources of innervation: an independent branch unrelated to the main trunk of the long thoracic nerve and the long thoracic nerve itself. The independent branch is related to branches from C4, C5, or C6, and its course is similar to that of the nerves responsible for the innervation of the levator scapulae muscle. As for the middle part of the serratus anterior, the long thoracic nerve descends on one-third of the anterior portion located between the origin and insertion. Finally, like the superior segment, the inferior part is also innervated by two sources: the long thoracic nerve and a branch of the intercostal nerve.

Muscles

The serratus anterior muscle is located deep to the subscapularis, from which it is separated by the subscapularis bursa or supraserratus bursa. The scapulothoracic bursa, or infraserratus bursa, separates the serratus anterior from the rib. The serratus anterior muscle is further subdivided into three parts according to their points of insertion and origins: serratus anterior superior, serratus anterior intermediate, and serratus anterior inferior. The serratus anterior superior originates from the first and second ribs, while the serratus anterior intermediate originates from the second and third ribs and the serratus anterior inferior from the fourth and ninth ribs. The superior segment serves as the main axis of rotation while the middle portion draws the scapula forward, and the inferior part rotates upward.[7]

Physiologic Variants

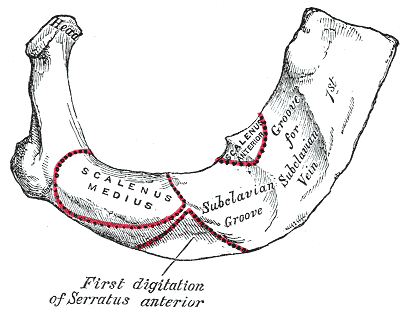

The rib attachments and origin of the serratus anterior may vary between each person (see Image. Peculiar Ribs, First Digitation of Serratus Anterior, Subclacius Groove). For instance, the serratus anterior can be found attached to the tenth rib, or attachments may be absent to the first rib. The serratus anterior fibers may sometimes be found in union with fibers of the levator scapulae, external intercostals, or external oblique muscles. Furthermore, there have been reported vascular variants, specifically in the blood supply to the serratus anterior myo-osseous flap, such that the lateral thoracic artery is the dominant supplier to the lower muscular slips.[8] Additionally, from harvested sixth and seventh ribs, the presence of vascular connections between the anteriorly placed lateral thoracic pedicle and the periosteum of the ribs was observed, which contrasts the more commonly described connections of the branches from the thoracodorsal pedicle.[9][10] Also, the serratus anterior's upper digitations may be innervated by C4 or C5 independently, without the nerves joining to form the main trunk of the long thoracic nerve.[6]

Surgical Considerations

A winged scapula is a condition that results from paralysis of the serratus anterior or trapezius muscles caused by damage to the long thoracic nerve or accessory nerves. This condition is apparent when the inferior angle of the scapula demonstrates a marked prominence, and there is a limited range of motion and reduced shoulder strength. Thoracic procedures, such as radical mastectomy, transthoracic sympathectomy, misplaced intercostal drains, axillary lymph node dissections, and resection of the first rib, increase the exposure of the long thoracic nerve and risk of nerve injury. Infants and children undergoing procedures requiring separation of the latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior muscles, such as a posterolateral thoracotomy incision for closed heart procedures, are at risk of long thoracic nerve injury and winged scapula. Noting the variants in the relation of the long thoracic nerve to the middle scalene muscle as it may lead to iatrogenic injury of the long thoracic nerve and subsequent scapular winging since the roots of the long thoracic nerve may lie posterior, anterior, or travel through the middle scalene muscle is also important.[11] Although the treatment for winged scapula is initially conservative with physical therapy as the mainstay, winged scapula secondary to serratus anterior palsy may be surgically treated with the split pectoralis major transfer without fascial graft. This technique entails transposing the sternal head of the pectoralis major from the humeral insertion to the inferomedial portion of the scapula.[6] Currently, nerve transfer and grafting have grown in popularity.

Clinical Significance

Repetitive microtrauma to the serratus anterior muscle may lead to the development of myofascial pain syndrome. Proposed mechanisms include prolonged, vigorous coughing, repeated lifting of heavy loads overhead, and long-distance running. Blunt trauma to the muscle itself may lead to serratus anterior myofascial pain syndrome. Patients with this syndrome complain of primary pain localized to the fifth to seventh ribs along the midaxillary line. Patients may also experience referred pain to the posterior chest wall, with radiation down the ipsilateral upper extremity to the palmar aspect of the fourth and fifth fingers.

Long thoracic nerve damage may result from nerve compression due to anesthesia or Saturday night palsy, which is a radial neuropathy due to falling asleep with one’s arm hanging over the armrest of a chair. Heavy load bearing may also entrap the nerve, resulting in atrophy of the serratus anterior and subsequent winging of the scapula. Athletics and overuse may lead to nerve traction. Electric shock, blunt injury, cold exposure, immunization, viral infection, and brachial neuritis are additional causes of nerve injury.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

External Abdominal Muscles. Pectoralis major, serratus anterior, latissimus dorsi, obliques externus, linea alba, inscriptiones tendineae, inguinal ligament, pubis, subcutaneous inguinal ring, lacunar ligament.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Surface Anatomy of the Thorax. The illustrated image depicts the left side of the thorax, trapezius, pectoralis major, serratus anterior, obliques externus, rectus abdominis, and latissimus dorsi.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Peculiar Ribs, First Digitation of Serratus Anterior, Subclavius Groove

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Nasu H, Yamaguchi K, Nimura A, Akita K. An anatomic study of structure and innervation of the serratus anterior muscle. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2012 Dec:34(10):921-8. doi: 10.1007/s00276-012-0984-1. Epub 2012 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 22638721]

Pu Q, Huang R, Brand-Saberi B. Development of the shoulder girdle musculature. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2016 Mar:245(3):342-50. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.24378. Epub 2016 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 26676088]

Gordon A, Alsayouri K. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Axilla. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31613503]

Laulan J, Lascar T, Saint-Cast Y, Chammas M, Le Nen D. Isolated paralysis of the serratus anterior muscle successfully treated by surgical release of the distal portion of the long thoracic nerve. Chirurgie de la main. 2011 Apr:30(2):90-6. doi: 10.1016/j.main.2011.02.003. Epub 2011 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 21507700]

Martin RM, Fish DE. Scapular winging: anatomical review, diagnosis, and treatments. Current reviews in musculoskeletal medicine. 2008 Mar:1(1):1-11. doi: 10.1007/s12178-007-9000-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19468892]

Vetter M, Charran O, Yilmaz E, Edwards B, Muhleman MA, Oskouian RJ, Tubbs RS, Loukas M. Winged Scapula: A Comprehensive Review of Surgical Treatment. Cureus. 2017 Dec 7:9(12):e1923. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1923. Epub 2017 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 29456903]

Gregg JR, Labosky D, Harty M, Lotke P, Ecker M, DiStefano V, Das M. Serratus anterior paralysis in the young athlete. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1979 Sep:61(6A):825-32 [PubMed PMID: 479228]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLipa JE, Chang DW. Lateral thoracic artery as a vascular variant in the supply to the free serratus anterior flap. Journal of reconstructive microsurgery. 2001 Aug:17(6):413-5 [PubMed PMID: 11507686]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBruck JC, Bier J, Kistler D. The serratus anterior osteocutaneous free flap. Journal of reconstructive microsurgery. 1990 Jul:6(3):209-13 [PubMed PMID: 2292781]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSabri F, Leclercq A, Vanwijck R. Surgical anatomy of the serratus anterior-rib composite flap. Acta chirurgica Belgica. 1993 Nov-Dec:93(6):271-5 [PubMed PMID: 8140839]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNadeau C, McGhee S, Gonzalez JM. Winged scapula: an overview of pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Emergency nurse : the journal of the RCN Accident and Emergency Nursing Association. 2021 Aug 31:29(5):28-31. doi: 10.7748/en.2021.e2110. Epub 2021 Jun 23 [PubMed PMID: 34159764]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence