Introduction

Genetic mosaicism is defined as the presence of two or more cell lineages with different genotypes arising from a single zygote in a single individual. In contrast, if distinct cell lines derived from different zygotes, the term is now known as chimerism. Genetic mosaicism is a postzygotic mutation.[1][2]

Since an adult human being requires countless cell divisions for its development (approximately 10 to the 16th power or, virtually, 10,000,000,000,000,000 mitoses) and every cell division carries a risk for genetic mistakes, each person has at least one genotypically distinct cell in their body; thus every individual is a mosaic. Also, probably all the cells within every single human being encompass numerous mutations that could potentially explain every human genetic disease. Nonetheless, only a minimum of these mutational events affects the individual’s well-being, while most are phenotypically silent (i.e., mutations are not relevant for cell function, mutant cells are eliminated by apoptosis). Mosaicism appears to be responsible for an enormous amount of pathologies, ranging from chromosomal abnormalities, such as Turner syndrome, to a myriad of cancers. Both benign and malignant tumors constitute evidence of somatic mosaicism in the human body.[3][4][5][6]

Development

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Development

A zygote in humans forms from the fusion of sperm (23 chromosomes) and an ovum (23 chromosomes), the zygote divides by mitosis to form the whole human body. Ideally, all descend of the zygote must have an identical genome, but it does not always happen. Mosaicism occurs at one of the stages after a zygote forms.[7][1]

Mosaicism is basically of two types:

- Somatic Mosaicism: More than one cell lineage in somatic cells, although, it does not pass to the offsprings as the sperm and oocytes (Germ cells) are not affected some recent studies shows the somatic mosaicism occurred during the preimplantation stage may affect both somatic and germline cells of the embryo.[8][9]

- Germline Mosaicism: More than one cell lineage in germline cells, this passes to the offspring. The individual will not be affected if only germline cells are mutated, but the mosaicism will pass to and may affect the offspring.[10][11][12]

Somatic or Constitutional mosaicism occurs at an embryonic or pre-embryonic stage and becomes an integral part of an organism. Conversely, somatic mosaicism arises exclusively from post-embryonic changes.[13][14] Constitutional/somatic mosaicism occurs due to errors in the segregation of chromosomes during mitosis or gametogenesis.[15]

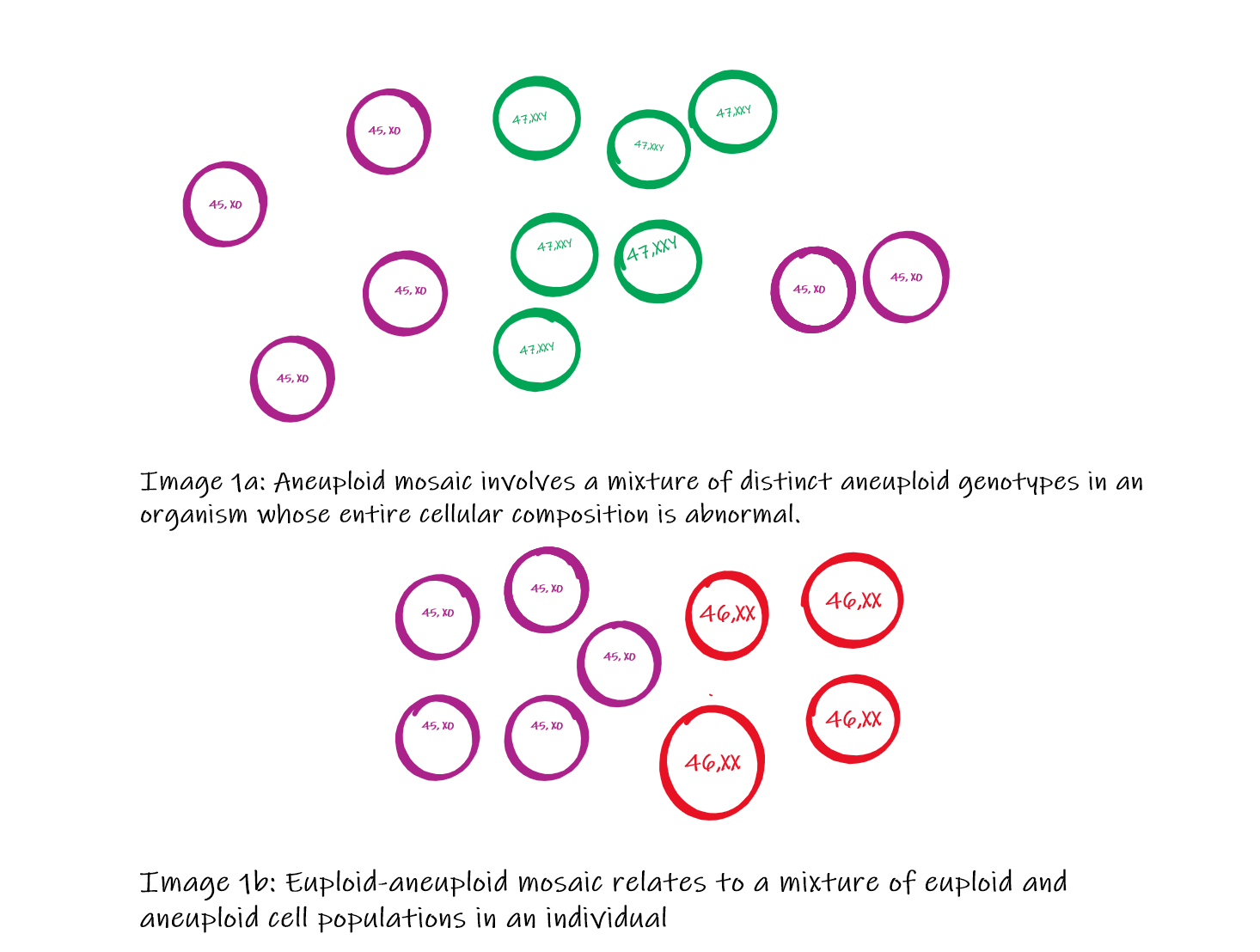

Mosaic embryos may be categorized into three groups (Image 1):

Aneuploid mosaic involves a mixture of distinct aneuploid genotypes in an organism whose entire cellular composition is abnormal.[16] Chromosomal Aneuploid mosaic whole chromosome is missing (45 chromosomes instead of 46) or one extra chromosome (47 chromosomes instead of 46) in a cell.[17][18]

Euploid-aneuploid mosaic relates to a mixture of euploid and aneuploid cell populations in an individual. Some cells of the body are aneuploid (45 or 47 chromosomes), while some are euploid (46 chromosomes). The severity of the clinical condition depends on the proportion of the euploid cells. This mosaicism is more common than as the embryo has more chances to survive during intrauterine life.[11][19]

Ploidy mosaics, commonly termed as mixoploid embryos, implicate a combination of different multiples of the normal haploid chromosome number.[20] An entire set of the chromosome is found access in a cell (e.g., triploidy 69 chromosomes, tetraploidy 92), embryos with predominant triploidy, or tetraploidy generally do not survive. Triploid and tetraploid cells can physiologically found in liver and bone marrow cells.[21][22][20]

The distribution and phenotypical findings largely depend on the precise time in which the mutation occurs during embryonic development. If a mutation arises during initial mitosis after fertilization, approximately half of all the individual’s cells will harbor the new mutation, which may manifest as a demarcation of affected and unaffected tissue along the midline. Likewise, although the exact moment of left-right separation in humans is unknown, mutation occurring after this dissociation present with affected cells and tissues that are less likely to cross the midline. Finally, mutations that occur before primordial germ cell differentiation (approximately before 15 mitotic divisions) may be present in both somatic and germ tissues. Otherwise, if emerging after this period, abnormal cells are confined to either somatic or germinal lineages. Therefore, establishing the timing of a mutation may suggest the proportion of mutant cells and, consequently, the potential recurrence risk for transmission of the same mutation to additional offspring.[6]

Cellular

On the base of cells affected, mosaicism can classify as two types.

General mosaicism: Two or more cell lines are present in the entire organism. The mosaicism should have been present before the differentiation starts. General mosaicism may also result because of affected paternal germ cell (sperm) and/or maternal germ cell (oocytes).[18][23][24]

Confined Mosaicism: In Confined mosaicism, only particular body parts or organs (e.g., brain, heart, liver, etc. ) are affected instead of the entire organism. Confined placental mosaicism may develop during the organogenesis or growth of the organ.[25][26]

The effect on the cell depends on the type of mutation in the genotype; cells with different genotypes may have identical structures without affecting the function. It may happen when the genotype variation is within the recessive or nonexpressive area of the chromosome.[27][28]

Mosaicism is the result of genetic alteration (Single nucleotide variants, chromosomal aberrations, copy number variants, etc.); that may be present in the germline or somatic cells of the body. Mosaicism may derive from the parental cells, or it may be sporadic. The tissues affected by the mosaicism depends on the amount and proportion of the cells affected. It may be restricted to non-gonadal tissue, gonadal tissue, or may affect all tissues of the body.[9][29]

Phenotypical expression depends on the number of cells affected. The phenotypical expression may happen during intrauterine life, after birth, or even in late-life on the base of the trigger factors.[30][31]

Biochemical

Gene-level mutations can also result in mosaicism by one of the following mechanisms. A single nucleotide changes, small insertion or deletion, trinucleotide repeat expansion and contraction, autonomous mobile element insertion, etc.[6]

Mutation in the chromosome or gene can affect the biochemical expression of the cell. It may affect the amount and/or quality of the biochemical expression of the cell. For example, the production of myelin basic protein (MBP) for the optic nerve and spinal cord is affected in heterozygous female mice for (rsh) rumpshaker, an X-linked mutation.[32] Tetrasomy 3q26.32-q29 may lead to hyperpigmentation.[33] In X-linked agammaglobulinemia, the individual fails to produce plasma cells and antibodies.[34]

Some studies reported Trisomy 13 mosaicism associated with reduced production of melanin (hypomelanosis) by Ito cells.[35]

Molecular Level

The early embryo is susceptible to mitotic errors due to the inactivation of the genome at fertilization. During the first three cell divisions, the embryo is dependent on oocyte cytoplasmic transcriptomes. Embryonic genome activation initiates after the third cleavage-stage; even some genes that encode critical proteins for cell division do not express until the blastocyst stage. Accordingly, laboratory detection of mosaicism has been reported as elevated as 70 and 90% of all cleavage- and blastocyst-stage embryos that derive from in vitro fertilization, respectively.[36][18]

Function

Depending on the population of cells affected, the mosaicism can affect the function.

Mosaicism expresses and affects the function as per the examples given below.

- Mosaic loss of chromosome Y in blood cells increases morbidity and mortality in old age.[37]

- Mosaic Klinefelter syndrome (46, XY/47, XXY) causes the small size of testes and reduced production of testosterone by the gonads.[38]

- Frequency of low-level and high-level mosaicism has a role in sporadic retinoblastoma severity and the onset of the retinoblastoma.[39]

- A mosaic variant on SMC1A has been found in buccal mucosa cells of Clinically diagnosed Cornelia de Lange syndrome (CdLS) patients.[40]

In some mosaics, the functions are not affected; it may be due to nonexpressive mutation, recessive mutation, or low amount of cells affected. It can be understood with the example of an X-linked recessive disorder.

X-Chromosome associated disorder like Rett's Syndrome, (Mutation of MECp2 gene) is fatal for male as the male have only one X chromosome. But if the male is mosaic for the specific gene, it means more cells are with normal X-chromosome than the male has chances of survival.[41]

Some investigators suggest that mosaicism may be a potential protective survival mechanism. Based on the fact that only a few autosomal and sex aneuploidies are compatible with human life (i.e., trisomy of chromosomes 13, 18, 21), a broader range of aneuploidies has been described in the mosaic state. For example, mosaic trisomies reported in the literature include chromosomes 8 (Warkany syndrome), 14, 16, and 17. Furthermore, while autosomal monosomy in humans is considered essentially lethal, with only a couple of cases reported for monosomy 21, a mosaic state worth noting involves isochromosome 12p, also known as Pallister–Killian syndrome. Survival is hypothetically possible due to the presence of a sufficient proportion of healthy cells.[5][6][42]

Mechanism

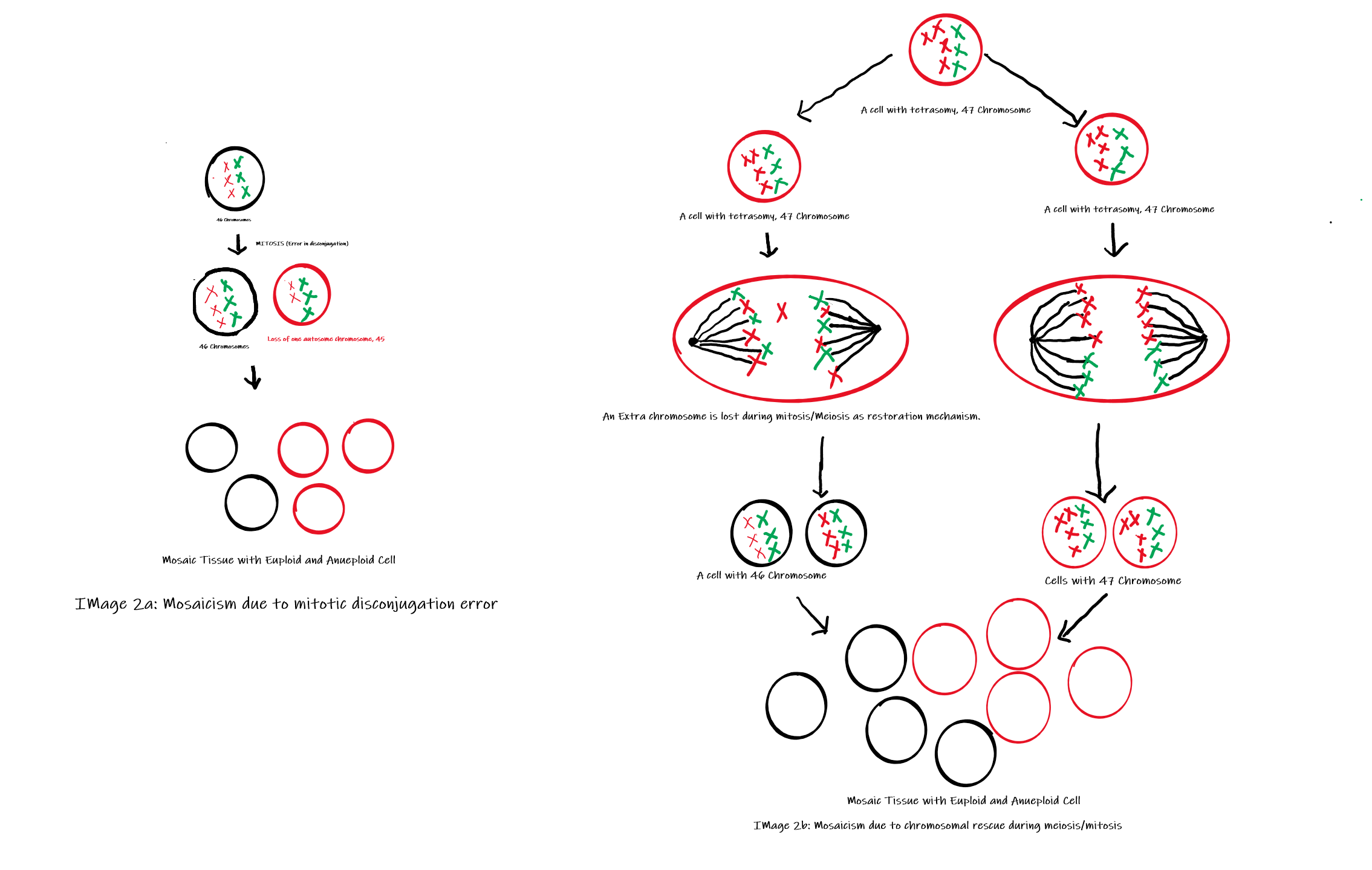

Somatic mosaicism may occur as a result of any type of mutation, ranging from chromosomal abnormalities to single nucleotide alterations. Mosaic aneuploidies are generated by two principal mechanisms (Image 2): post-zygotic mitotic non-disjunction or post-zygotic mitotic trisomy rescue after a meiotic non-disjunction. The second indicates a biological attempt to restore the normal chromosome number, which is known as a chromosomal rescue. This mechanism is achieved through the loss of one random supernumerary chromosome in a somatic cell, restoring the euploid state. Nonetheless, chromosome rescue constitutes an increased risk for uniparental disomy, thereby interfering with genomic imprinting and elevating the likelihood of homozygosity for a recessive mutation.[5][6][43] Other mechanisms that can cause mosaicism include anaphase lagging and endoreplication.[18]

Testing

The identification of mosaic embryos has become feasible for up to 8–10 weeks of fetal development via prenatal diagnosis. The most commonly performed procedures in clinical practice include amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling; both carry their own risks and benefits.[13]

Amniocentesis: Amniotic fluid from the uterus is aspirated around the 15th week of pregnancy, amniocentesis performed before the 15th week has more chances of damage to the embryo.[44][45]

Chorionic Villus sampling: Cells of Chorionic villi are aspirated earliest at the 10th week for the genetic analysis.[44]

Embryo tissue is not taken as samples in any of the above two techniques.

Multiple techniques have been developed to detect mosaicism and other chromosome abnormalities.

Karyotyping: The simplest method to detect different genetic compositions from a single individual is karyotype analysis. Cytogenetic analysis is routinely used in the clinical practice and allows evaluation of the cellular genetic material (numerical or structural alterations such as translocations and large [>5 Mb] deletions or duplications). However, this approach enables examination only at the chromosomal level; thus, very low levels of mosaicism are detected. [46] In contrast, fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) is another technique that allows greater analysis of smaller copy-number variations (50 kb) in a broad number of interphase cells. Therefore, the major challenge remains on the number of cells visualized, which typically requires a large number of cells, even in high levels of mosaicism.[47][48]

Moreover, Sanger sequencing offers the possibility of a single nucleotide examination and continues to be a useful screening tool in some institutions for specific gene analysis. Nevertheless, the former methods are slowly being replaced by two more time-efficient methods that assess all the cellular genome simultaneously.[5][6][49] These approaches include chromosomal microarray (CMA) and next-generation sequencing (NGS).

Chromosomal microarray (CMA) can identify copy-number variations without having the limitation of cells being cultured at a specific cycle stage. CMA may classify into comparative genomic hybridization arrays (aCGH) and single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) arrays. Previous studies suggest a detection capacity for mosaicism at 10-20% and 5% levels for aCGH and SNP, respectively.[46][50][51]

Alternatively, next-generation sequencing (NGS) distinguishes small genetic changes such as insertions, deletions, and single nucleotide variants within a whole genome with much higher sequencing depth. This tool may be used for mosaicism identification since it allows manual exploration of each scan.[5][52]

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) is more specific and can identify nucleotide level mutations. It is preferred in adults and preimplantation embryo for assisted reproductive techniques.

Pathophysiology

Mutation at the gene and/or chromosomal level may lead to chromosomal instability leading to cells with different genotypes. Mosaic chromosomal aberrations lead to abnormal phenotypes that also include irregular or altered production of protein.[53]

The altered phenotype of a group of cells is expressed as clinical manifestation also; which can be understood by the following examples.

- A somatic chromosomal aberration has a role in production amyloid precursor protein that may affect neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's disease.[54]

- In trisomy 21 down syndrome, a significant difference has been found in Intelligent Quotient between-group without mosaicism and a group with mosaicism [individuals have both trisomic (47, XX,+21 or 47, XY,+21) and euploid (46, XX or 46, XY) cell lines].[55]

- In patients with Turner syndrome with mosaicism, the loss of the X chromosome may have happened during cell division of early embryonic stages. That results in some cells have only one copy of the X chromosome (45, 21+X0), and some cells have two copies of X chromosomes (46, 21 + XX). The mosaic individual has less severity of symptoms.[56]

In brief, a cascade can be described as following in somatic mosaicism.[57][58][59][3][60][61][11]

- An altered genome during mitosis or meiosis

- Cells with two or more types of genotypes

- The function of the cell is affected e.g., secretion of the protein, production of the hormone, etc. (e.g., Decreased production of testosterone in Klinefelter syndrome).

- Depending on the population of the affected cells, the tissue function may also deteriorate (the more cells with mutated genome the more the function is affected. The hormonal effect on organs in Turner syndrome, demyelinated cells in neurodegenerative diseases).

- Expression as clinical symptoms (e.g., Low intelligent quotients in turner syndrome, dementia in Alzheimer disease, gynecomastia in Klinefelter syndrome)

- In some cases, mutated cells may proliferate because of the triggering factor and lead to malignant condition also (e.g., somatic genomic mosaicism in multiple myeloma, ovarian carcinoma)

For germline cell mosaicism:[62][63][64][11][65]

- The germ cells mutate during meiosis (e.g., some sperms with 22, X0, some sperms with 24, XXY). The affected person does not show any symptoms, but it passes to the offspring.

- Affected germ cells fuse with normal/abnormal germ cells (e.g., sperm with 22, X0 fuses with oocyte with 23, XX) forms with two lineages of somatic cells (45, X0 and 46, XX)

- Now on the base of the population of the abnormal somatic cells, the offspring expresses phenotypes as it does in somatic mosaicism.

Clinical Significance

Mosaicism has important implications for genetic counseling when detected in prenatal diagnostic studies.[66] Nondisjunction occurs more commonly during oogenesis than in spermatogenesis. The recurrent risk of mosaicism is unknown; gonadal mosaicism should be contemplated, particularly in situations where an offspring has a nonmosaic trisomy for a specific chromosome. Germline mosaicism may contribute to familial aggregation of affected individuals and establishes a fundamental explanation for the recurrence of rare mutations within a single-family.[67] Since each affected chromosome has distinct clinical manifestations, genetic counseling depends upon the nature of the mosaicism.[13]

Mosaicism affects the survival rates in monosomies: In humans, monosomies are fatal, but mosaic monosomies (in case more than 70% of cells are normal and remaining are monosomes) may survive after birth.[68][69]

Mosaicism leads to malignant condition: Gradual loss of specific human genome is evident with aging; that leads to mosaicism in the tissue. The mosaic tissue may convert into malignant tissue also (e.g., neurofibromatosis).[59][3]

Single gene diseases also show relations with mosaicism:

- Mutation in fumarylacetoacetate hydrolase (FAH) gene leading to hereditary tyrosinemia type 1; the liver cells of the patient are mosaic (some cells normal, some mutated).[70][66]

- Mutation in the BLM gene; BLM gene encodes a DNA helicase enzyme that has a role in DNA replication. The mutation leads to Bloom syndrome characterized as the predisposition of malignancy, growth disorder, and immunodeficiency.[71][72]

- Dystrophin gene mosaicism in Duchene muscular dystrophy.[73]

In vitro fertilization technique has high chances of mutation and mosaicism that may affect the embryo, so preimplantation screening for mosaicism and mutation is practiced in many centers to avoid genetic diseases.[11][52][23]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

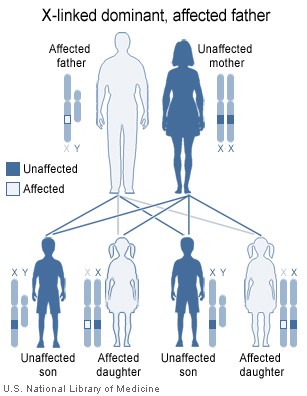

Image showing inheritance of X-linked dominant mutation from an affected father, The sons of a man with an X-linked dominant disorder will not be affected, but his daughters will all inherit the condition Contributed by National Institute of Health ( http://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/handbook/illustrations/xlinkdominantfather )

(Click Image to Enlarge)

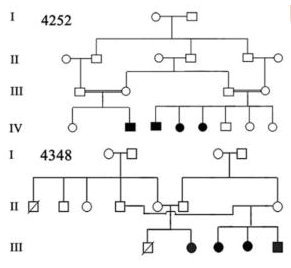

Image 1: Pedigree of a Prevalent Autosomal Recessive Disease Contributed by Chishti, Muhammad S et al. “Splice-site mutations in the TRIC gene underlie autosomal recessive nonsyndromic hearing impairment in Pakistani families.” Journal of human genetics vol. 53,2 (2008): 101-5. doi:10.1007/s10038-007-0209-3 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2757049/)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Foulkes WD, Real FX. Many mosaic mutations. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont.). 2013 Apr:20(2):85-7. doi: 10.3747/co.20.1449. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23559869]

Moog U, Felbor U, Has C, Zirn B. Disorders Caused by Genetic Mosaicism. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2020 Feb 21:116(8):119-125. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0119. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32181732]

Machiela MJ. Mosaicism, aging and cancer. Current opinion in oncology. 2019 Mar:31(2):108-113. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000500. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30585859]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBanka S,Metcalfe K,Clayton-Smith J, Trisomy 18 mosaicism: report of two cases. World journal of pediatrics : WJP. 2013 May; [PubMed PMID: 22105572]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCohen AS, Wilson SL, Trinh J, Ye XC. Detecting somatic mosaicism: considerations and clinical implications. Clinical genetics. 2015 Jun:87(6):554-62. doi: 10.1111/cge.12502. Epub 2014 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 25223253]

Campbell IM, Shaw CA, Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Somatic mosaicism: implications for disease and transmission genetics. Trends in genetics : TIG. 2015 Jul:31(7):382-92. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.03.013. Epub 2015 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 25910407]

Popovic M, Dhaenens L, Boel A, Menten B, Heindryckx B. Chromosomal mosaicism in human blastocysts: the ultimate diagnostic dilemma. Human reproduction update. 2020 Apr 15:26(3):313-334. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmz050. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32141501]

Holstege H, Pfeiffer W, Sie D, Hulsman M, Nicholas TJ, Lee CC, Ross T, Lin J, Miller MA, Ylstra B, Meijers-Heijboer H, Brugman MH, Staal FJ, Holstege G, Reinders MJ, Harkins TT, Levy S, Sistermans EA. Somatic mutations found in the healthy blood compartment of a 115-yr-old woman demonstrate oligoclonal hematopoiesis. Genome research. 2014 May:24(5):733-42. doi: 10.1101/gr.162131.113. Epub 2014 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 24760347]

Gajecka M. Unrevealed mosaicism in the next-generation sequencing era. Molecular genetics and genomics : MGG. 2016 Apr:291(2):513-30. doi: 10.1007/s00438-015-1130-7. Epub 2015 Oct 19 [PubMed PMID: 26481646]

Chen T, Tian L, Wang X, Fan D, Ma G, Tang R, Xuan X. Possible misdiagnosis of 46,XX testicular disorders of sex development in infertile males. International journal of medical sciences. 2020:17(9):1136-1141. doi: 10.7150/ijms.46058. Epub 2020 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 32547308]

Miles B, Tadi P. Genetics, Somatic Mutation. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491819]

Basta M, Pandya AM. Genetics, X-Linked Inheritance. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491315]

Verma RS, Kleyman SM, Conte RA. Chromosomal mosaicisms during prenatal diagnosis. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation. 1998:45(1):12-5 [PubMed PMID: 9473156]

Lee HY,Koo DW,Lee JS, Lichen striatus colocalized with Becker's nevus: a case with two types of simultaneous cutaneous mosaicism? International journal of dermatology. 2020 Jun 3; [PubMed PMID: 32492173]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBielanska M, Tan SL, Ao A. Chromosomal mosaicism throughout human preimplantation development in vitro: incidence, type, and relevance to embryo outcome. Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 2002 Feb:17(2):413-9 [PubMed PMID: 11821287]

Singla S, Iwamoto-Stohl LK, Zhu M, Zernicka-Goetz M. Autophagy-mediated apoptosis eliminates aneuploid cells in a mouse model of chromosome mosaicism. Nature communications. 2020 Jun 11:11(1):2958. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16796-3. Epub 2020 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 32528010]

Ge Y, Zhang J, Cai M, Chen X, Zhou Y. [Prenatal genetic analysis of three fetuses with abnormalities of chromosome 22]. Zhonghua yi xue yi chuan xue za zhi = Zhonghua yixue yichuanxue zazhi = Chinese journal of medical genetics. 2020 Apr 10:37(4):405-409. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2020.04.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32219823]

Taylor TH, Gitlin SA, Patrick JL, Crain JL, Wilson JM, Griffin DK. The origin, mechanisms, incidence and clinical consequences of chromosomal mosaicism in humans. Human reproduction update. 2014 Jul-Aug:20(4):571-81. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmu016. Epub 2014 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 24667481]

Ramos C, Ocampos M, Barbato IT, Graça Bicalho MD, Nisihara R. Molecular analysis of FMR1 gene in a population in Southern Brazil: Comparison of four methods. Practical laboratory medicine. 2020 Aug:21():e00162. doi: 10.1016/j.plabm.2020.e00162. Epub 2020 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 32426440]

McCoy RC. Mosaicism in Preimplantation Human Embryos: When Chromosomal Abnormalities Are the Norm. Trends in genetics : TIG. 2017 Jul:33(7):448-463. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2017.04.001. Epub 2017 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 28457629]

Dörnen J, Sieler M, Weiler J, Keil S, Dittmar T. Cell Fusion-Mediated Tissue Regeneration as an Inducer of Polyploidy and Aneuploidy. International journal of molecular sciences. 2020 Mar 6:21(5):. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051811. Epub 2020 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 32155721]

Jang J, Engleka KA, Liu F, Li L, Song G, Epstein JA, Li D. An Engineered Mouse to Identify Proliferating Cells and Their Derivatives. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2020:8():388. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2020.00388. Epub 2020 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 32523954]

Zachaki S, Kouvidi E, Pantou A, Tsarouha H, Mitrakos A, Tounta G, Charalampous I, Manola KN, Kanavakis E, Mavrou A. Low-level X Chromosome Mosaicism: A Common Finding in Women Undergoing IVF. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2020 May-Jun:34(3):1433-1437. doi: 10.21873/invivo.11925. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32354942]

Middelkamp S, van Tol HTA, Spierings DCJ, Boymans S, Guryev V, Roelen BAJ, Lansdorp PM, Cuppen E, Kuijk EW. Sperm DNA damage causes genomic instability in early embryonic development. Science advances. 2020 Apr:6(16):eaaz7602. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aaz7602. Epub 2020 Apr 15 [PubMed PMID: 32494621]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNeofytou M. Predicting fetoplacental mosaicism during cfDNA-based NIPT. Current opinion in obstetrics & gynecology. 2020 Apr:32(2):152-158. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0000000000000610. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31977337]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBlakey-Cheung S, Parker P, Schlaff W, Monseur B, Keppler-Noreuil K, Al-Kouatly HB. Diagnosis and clinical delineation of mosaic tetrasomy 5p. European journal of medical genetics. 2020 Jan:63(1):103634. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2019.02.006. Epub 2019 Feb 21 [PubMed PMID: 30797979]

Grønskov K, Rosenberg T, Sand A, Brøndum-Nielsen K. Mutational analysis of PAX6: 16 novel mutations including 5 missense mutations with a mild aniridia phenotype. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 1999 Apr:7(3):274-86 [PubMed PMID: 10234503]

Dubey SK, Mahalaxmi N, Vijayalakshmi P, Sundaresan P. Mutational analysis and genotype-phenotype correlations in southern Indian patients with sporadic and familial aniridia. Molecular vision. 2015:21():88-97 [PubMed PMID: 25678763]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCôté GB. The cis-trans effects of crossing-over on the penetrance and expressivity of dominantly inherited disorders. Annales de genetique. 1989:32(3):132-5 [PubMed PMID: 2817771]

Tesner P, Drabova J, Stolfa M, Kudr M, Kyncl M, Moslerova V, Novotna D, Kremlikova Pourova R, Kocarek E, Rasplickova T, Sedlacek Z, Vlckova M. A boy with developmental delay and mosaic supernumerary inv dup(5)(p15.33p15.1) leading to distal 5p tetrasomy - case report and review of the literature. Molecular cytogenetics. 2018:11():29. doi: 10.1186/s13039-018-0377-1. Epub 2018 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 29760779]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGaspar IM, Gaspar A. Variable expression and penetrance in Portuguese families with Familial Hypercholesterolemia with mild phenotype. Atherosclerosis. Supplements. 2019 Mar:36():28-30. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2019.01.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30876530]

Fanarraga ML,Griffiths IR,McCulloch MC,Barrie JA,Cattanach BM,Brophy PJ,Kennedy PG, Rumpshaker: an X-linked mutation affecting CNS myelination. A study of the female heterozygote. Neuropathology and applied neurobiology. 1991 Aug [PubMed PMID: 1944806]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCunha KS, Simioni M, Vieira TP, Gil-da-Silva-Lopes VL, Puzzi MB, Steiner CE. Tetrasomy 3q26.32-q29 due to a supernumerary marker chromosome in a child with pigmentary mosaicism of Ito. Genetics and molecular biology. 2016 Mar:39(1):35-9. doi: 10.1590/1678-4685-GMB-2015-0033. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27007896]

Mazhar M, Waseem M. Agammaglobulinemia. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32310401]

Dhar SU, Robbins-Furman P, Levy ML, Patel A, Scaglia F. Tetrasomy 13q mosaicism associated with phylloid hypomelanosis and precocious puberty. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2009 May:149A(5):993-6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32758. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19334087]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSachdev NM, Maxwell SM, Besser AG, Grifo JA. Diagnosis and clinical management of embryonic mosaicism. Fertility and sterility. 2017 Jan:107(1):6-11. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2016.10.006. Epub 2016 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 27842993]

Guo X, Dai X, Zhou T, Wang H, Ni J, Xue J, Wang X. Mosaic loss of human Y chromosome: what, how and why. Human genetics. 2020 Apr:139(4):421-446. doi: 10.1007/s00439-020-02114-w. Epub 2020 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 32020362]

Zitzmann M, Rohayem J. Gonadal dysfunction and beyond: Clinical challenges in children, adolescents, and adults with 47,XXY Klinefelter syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2020 Jun:184(2):302-312. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31786. Epub 2020 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 32415901]

Rodríguez-Martín C, Robledo C, Gómez-Mariano G, Monzón S, Sastre A, Abelairas J, Sábado C, Martín-Begué N, Ferreres JC, Fernández-Teijeiro A, González-Campora R, Rios-Moreno MJ, Zaballos Á, Cuesta I, Martínez-Delgado B, Posada M, Alonso J. Frequency of low-level and high-level mosaicism in sporadic retinoblastoma: genotype-phenotype relationships. Journal of human genetics. 2020 Jan:65(2):165-174. doi: 10.1038/s10038-019-0696-z. Epub 2019 Nov 26 [PubMed PMID: 31772335]

Gonzalez Garcia A, Malone J, Li H. A novel mosaic variant on SMC1A reported in buccal mucosa cells, albeit not in blood, of a patient with Cornelia de Lange-like presentation. Cold Spring Harbor molecular case studies. 2020 Jun:6(3):. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a005322. Epub 2020 Jun 12 [PubMed PMID: 32532882]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTakeguchi R, Takahashi S, Kuroda M, Tanaka R, Suzuki N, Tomonoh Y, Ihara Y, Sugiyama N, Itoh M. MeCP2_e2 partially compensates for lack of MeCP2_e1: A male case of Rett syndrome. Molecular genetics & genomic medicine. 2020 Feb:8(2):e1088. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1088. Epub 2019 Dec 9 [PubMed PMID: 31816669]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceQueremel Milani DA, Tadi P. Genetics, Chromosome Abnormalities. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491623]

Grati FR, Malvestiti F, Branca L, Agrati C, Maggi F, Simoni G. Chromosomal mosaicism in the fetoplacental unit. Best practice & research. Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2017 Jul:42():39-52. doi: 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2017.02.004. Epub 2017 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 28284509]

Alfirevic Z, Navaratnam K, Mujezinovic F. Amniocentesis and chorionic villus sampling for prenatal diagnosis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Sep 4:9(9):CD003252. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003252.pub2. Epub 2017 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 28869276]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTara F,Lotfalizadeh M,Moeindarbari S, The effect of diagnostic amniocentesis and its complications on early spontaneous abortion. Electronic physician. 2016 Aug [PubMed PMID: 27757190]

Wapner RJ, Martin CL, Levy B, Ballif BC, Eng CM, Zachary JM, Savage M, Platt LD, Saltzman D, Grobman WA, Klugman S, Scholl T, Simpson JL, McCall K, Aggarwal VS, Bunke B, Nahum O, Patel A, Lamb AN, Thom EA, Beaudet AL, Ledbetter DH, Shaffer LG, Jackson L. Chromosomal microarray versus karyotyping for prenatal diagnosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Dec 6:367(23):2175-84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1203382. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23215555]

Iwata-Otsubo A, Radke B, Findley S, Abernathy B, Vallejos CE, Jackson SA. Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)-Based Karyotyping Reveals Rapid Evolution of Centromeric and Subtelomeric Repeats in Common Bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) and Relatives. G3 (Bethesda, Md.). 2016 Apr 7:6(4):1013-22. doi: 10.1534/g3.115.024984. Epub 2016 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 26865698]

Findlay I, Corby N, Rutherford A, Quirke P. Comparison of FISH PRINS, and conventional and fluorescent PCR for single-cell sexing: suitability for preimplantation genetic diagnosis. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics. 1998 May:15(5):258-65 [PubMed PMID: 9604757]

Notini AJ, Craig JM, White SJ. Copy number variation and mosaicism. Cytogenetic and genome research. 2008:123(1-4):270-7. doi: 10.1159/000184717. Epub 2009 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 19287164]

Shah MS, Cinnioglu C, Maisenbacher M, Comstock I, Kort J, Lathi RB. Comparison of cytogenetics and molecular karyotyping for chromosome testing of miscarriage specimens. Fertility and sterility. 2017 Apr:107(4):1028-1033. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2017.01.022. Epub 2017 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 28283267]

Cheng SSW, Chan KYK, Leung KKP, Au PKC, Tam WK, Li SKM, Luk HM, Kan ASY, Chung BHY, Lo IFM, Tang MHY. Experience of chromosomal microarray applied in prenatal and postnatal settings in Hong Kong. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2019 Jun:181(2):196-207. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31697. Epub 2019 Mar 23 [PubMed PMID: 30903683]

Shi Q, Qiu Y, Xu C, Yang H, Li C, Li N, Gao Y, Yu C. Next-generation sequencing analysis of each blastomere in good-quality embryos: insights into the origins and mechanisms of embryonic aneuploidy in cleavage-stage embryos. Journal of assisted reproduction and genetics. 2020 Jul:37(7):1711-1718. doi: 10.1007/s10815-020-01803-9. Epub 2020 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 32445153]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePaththinige CS, Sirisena ND, Kariyawasam UGIU, Dissanayake VHW. The Frequency and Spectrum of Chromosomal Translocations in a Cohort of Sri Lankans. BioMed research international. 2019:2019():9797104. doi: 10.1155/2019/9797104. Epub 2019 Apr 2 [PubMed PMID: 31061830]

Kaeser GE, Chun J. Mosaic Somatic Gene Recombination as a Potentially Unifying Hypothesis for Alzheimer's Disease. Frontiers in genetics. 2020:11():390. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2020.00390. Epub 2020 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 32457796]

Papavassiliou P, York TP, Gursoy N, Hill G, Nicely LV, Sundaram U, McClain A, Aggen SH, Eaves L, Riley B, Jackson-Cook C. The phenotype of persons having mosaicism for trisomy 21/Down syndrome reflects the percentage of trisomic cells present in different tissues. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2009 Feb 15:149A(4):573-83. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32729. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19291777]

Armstrong JM, Malhotra NR, Lau GA. Seminoma In A Young Phenotypic Female With Turner Syndrome 45,XO/46,XY Mosaicism: A Case Report With Review Of The Literature. Urology. 2020 May:139():168-170. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2020.01.031. Epub 2020 Feb 10 [PubMed PMID: 32057790]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCastori M, Tadini G. Discoveries and controversies in cutaneous mosaicism. Giornale italiano di dermatologia e venereologia : organo ufficiale, Societa italiana di dermatologia e sifilografia. 2016 Jun:151(3):251-65 [PubMed PMID: 27070303]

Lichtenstein AV. Genetic Mosaicism and Cancer: Cause and Effect. Cancer research. 2018 Mar 15:78(6):1375-1378. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2769. Epub 2018 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 29472519]

Cohen PR, Segmental neurofibromatosis and cancer: report of triple malignancy in a woman with mosaic Neurofibromatosis 1 and review of neoplasms in segmental neurofibromatosis. Dermatology online journal. 2016 Jul 15; [PubMed PMID: 27617721]

Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB, Kutsev SI. Ontogenetic and Pathogenetic Views on Somatic Chromosomal Mosaicism. Genes. 2019 May 19:10(5):. doi: 10.3390/genes10050379. Epub 2019 May 19 [PubMed PMID: 31109140]

Jelsig AM,Bertelsen B,Forss I,Karstensen JG, Two cases of somatic STK11 mosaicism in Danish patients with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome. Familial cancer. 2021 Jan [PubMed PMID: 32504210]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTournier-Lasserve E. Molecular Genetic Screening of CCM Patients: An Overview. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.). 2020:2152():49-57. doi: 10.1007/978-1-0716-0640-7_4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32524543]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMuyas F, Zapata L, Guigó R, Ossowski S. The rate and spectrum of mosaic mutations during embryogenesis revealed by RNA sequencing of 49 tissues. Genome medicine. 2020 May 27:12(1):49. doi: 10.1186/s13073-020-00746-1. Epub 2020 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 32460841]

Sasani TA,Pedersen BS,Gao Z,Baird L,Przeworski M,Jorde LB,Quinlan AR, Large, three-generation human families reveal post-zygotic mosaicism and variability in germline mutation accumulation. eLife. 2019 Sep 24; [PubMed PMID: 31549960]

Navarro-Cobos MJ, Balaton BP, Brown CJ. Genes that escape from X-chromosome inactivation: Potential contributors to Klinefelter syndrome. American journal of medical genetics. Part C, Seminars in medical genetics. 2020 Jun:184(2):226-238. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31800. Epub 2020 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 32441398]

Youssoufian H,Pyeritz RE, Mechanisms and consequences of somatic mosaicism in humans. Nature reviews. Genetics. 2002 Oct [PubMed PMID: 12360233]

Hall JG, Review and hypotheses: somatic mosaicism: observations related to clinical genetics. American journal of human genetics. 1988 Oct [PubMed PMID: 3052049]

Hook EB, Warburton D. Turner syndrome revisited: review of new data supports the hypothesis that all viable 45,X cases are cryptic mosaics with a rescue cell line, implying an origin by mitotic loss. Human genetics. 2014 Apr:133(4):417-24. doi: 10.1007/s00439-014-1420-x. Epub 2014 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 24477775]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHu Q,Chai H,Shu W,Li P, Human ring chromosome registry for cases in the Chinese population: re-emphasizing Cytogenomic and clinical heterogeneity and reviewing diagnostic and treatment strategies. Molecular cytogenetics. 2018; [PubMed PMID: 29492108]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan Dyk E, Pretorius PJ. Point mutation instability (PIN) mutator phenotype as model for true back mutations seen in hereditary tyrosinemia type 1 - a hypothesis. Journal of inherited metabolic disease. 2012 May:35(3):407-11. doi: 10.1007/s10545-011-9401-x. Epub 2011 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 22002443]

Ellis NA, Ciocci S, German J. Back mutation can produce phenotype reversion in Bloom syndrome somatic cells. Human genetics. 2001 Feb:108(2):167-73 [PubMed PMID: 11281456]

Hirschhorn R. In vivo reversion to normal of inherited mutations in humans. Journal of medical genetics. 2003 Oct:40(10):721-8 [PubMed PMID: 14569115]

Xiao H, Zhang Z, Li T, Zhang Q, Guo Q, Wu D, Wang H, Zhang M, Gao Y, Liao S. [Germinal mosaicism for partial deletion of the Dystrophin gene in a family affected with Duchenne muscular dystrophy]. Zhonghua yi xue yi chuan xue za zhi = Zhonghua yixue yichuanxue zazhi = Chinese journal of medical genetics. 2019 Oct 10:36(10):1015-1018. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1003-9406.2019.10.016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31598949]