Introduction

Congenital auricular abnormalities occur in up to 20% of live births, ranging in severity from mild asymmetry to complete absence of an external ear.[1] Among the most common deformities are the "lop ear," in which the antihelix is incompletely folded, and the "cup ear," in which the conchal bowl is unusually deep due to an excess of cartilage (see Image. Lop Ear Deformity). Less commonly, patients present with other malformations, including Stahl ear, cryptotia, and microtia; correction of these anomalies may require anything from molding of the neonate's ear for the first few weeks of life to construction of an entire auricle using costal cartilage, fascial flaps, and skin grafts. Otoplasty, however, is not solely employed to correct congenital abnormalities. The procedure may also be applied to repair acquired auricular deformities due to trauma, such as "cauliflower ear" (see Image. Cauliflower Ear).

While many methods have been developed to correct congenital auricular anomalies, the landmark techniques are comparatively few. In 1963, Mustardé reported using conchoscaphal sutures to create or refine the antihelical fold, improving the appearance of the auricle and reducing its prominence.[2] Furnas followed 5 years later, describing the placement of conchomastoid sutures between the mastoid periosteum and the posterior aspect of the conchal bowl to reduce excessive prominence of the auricle, also known as prominauris.[3] For more severe deformities, microtia in particular, Brent published his 20-year experience with a 4-stage operation in 1992, and a 2-stage procedure was subsequently popularized by Nagata the following year.[4][5] Beyond these well-known techniques, however, a broad spectrum of interventions has evolved over many decades to address congenital and acquired auricular malformations.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

Development of the ear begins with the otic placode, which appears during the third week of gestation. The elastic cartilage of the auricle begins forming from the ectoderm of the first and second pharyngeal, or "branchial," arches by week 6 via the hillocks of His. The hillocks are 6 excrescences that arise in 2 rows of 3, with the first row (hillocks 1-3) originating from the first pharyngeal arch and the second row (hillocks 4-6) coming from the second pharyngeal arch. The relationship between the first 3 hillocks of His and the Meckel cartilage of the first pharyngeal arch underpins the coincidence of microtia and hemifacial microsomia.

Some debate remains regarding which auricular structures arise from which hillocks of His, but a commonly held theory is that the first hillock becomes the tragus, the second the helical crus, and the third the helix. The fourth hillock gives rise to the antihelical crura, the fifth to the stem of the antihelix, and the sixth to the antitragus.[6] The auricular lobule, which has no cartilage, does not develop from the hillocks. The rest of the pinna is supported by cartilage, though, and the skin of the anterior aspect of the auricle adheres tightly to it. At the same time, there is a loose areolar layer between the skin and cartilage posteriorly.

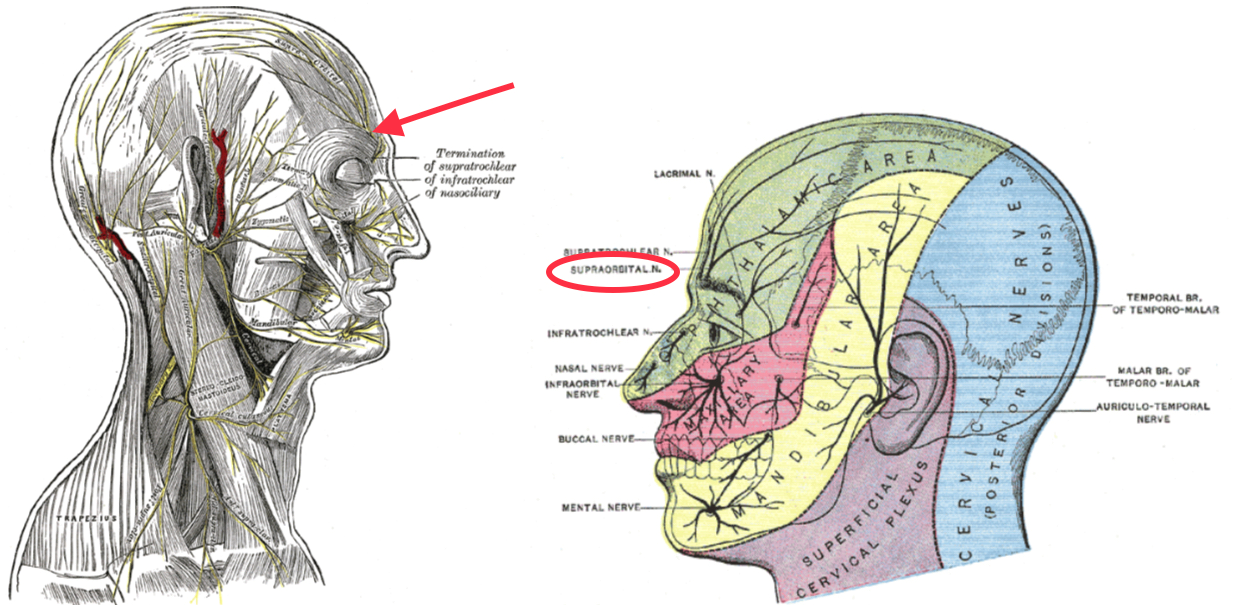

The innervation of the external ear is complex and involves multiple cranial nerves, including the auriculotemporal nerve from the trigeminal nerve anteriorly, the Jacobson nerve branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve in the middle ear, the Arnold nerve branch of the vagus nerve in the external auditory canal, nerves from the second and third cervical plexus posteriorly and inferiorly (as the lesser occipital and greater auricular nerves, respectively), and the sensory auricular branch of the facial nerve in the external auditory meatus (see Image. Sensory Areas of the Head).[7] As a result, adequate local anesthesia can be difficult to achieve.

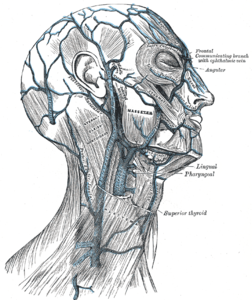

The extrinsic muscles of the ear, including the superior auricular muscle, the temporoparietalis muscle, the posterior auricular muscle, and the anterior auricular muscle, as well as the intrinsic muscles—the helicis major and minor, the tragicus, the antitragicus, and the transverse and oblique auricular muscles—are all also innervated by the facial nerve. However, these muscles are largely irrelevant to the pinna's form, function, or reconstruction (see Image. The Muscles of the Ear). The external ear receives its vascular supply via the superficial temporal artery anteriorly and the posterior auricular and lesser occipital arteries posteriorly—all branches of the external carotid system—and drains via branches of the external and internal jugular venous systems, chiefly the superficial temporal and posterior auricular veins (see Images. Arteries of the Head and Face and Veins of the Scalp).

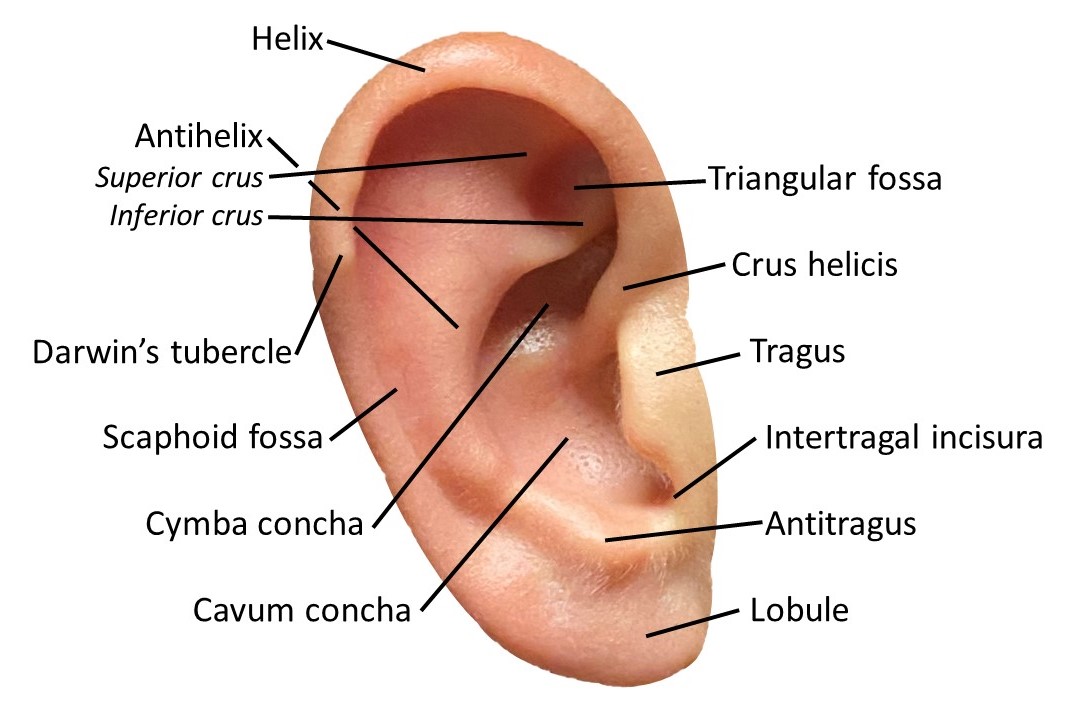

In standard otoplasty, improving the definition of the antihelix and adjusting the conchal bowl are among the most common maneuvers. The antihelix is the curvilinear fold between the helix and the conchal bowl. Inferiorly, this fold ends at the antitragus; superiorly, it divides into superior and inferior crura, which, together with the helix itself, define the triangular fossa (see Image. Auricle Surface Anatomy). The helix constitutes the outer rim of the auricle, beginning as the helical crus, or "root," which separates the conchal bowl into the cymba concha superiorly and cavum concha inferiorly. From there, the helix spirals anteriorly and superiorly, posteriorly, and inferiorly towards the lobule. Despite appearing to be a well-formed ridge, the inferior portion of the helix lacks cartilage below the cauda helicis, which is important to know when attempting to adjust the inferior portion of the auricle, particularly in the case of an outstanding lobule (see Image. Cranial Surface of the Right Auricular Cartilage).

The other notable structures of the auricle are the tragus, which is a cartilaginous prominence that protects the external auditory meatus; the Darwin tubercle, which is a localized thickening at the posterior aspect of the helix not present in all auricles; the intertragal incisura between the tragus and the antitragus; and the scaphoid fossa, which separates the helix from the antihelix. Any of these structures may be malformed, but fortunately, clinically significant conductive hearing loss does not result from auricular malformations unless there is stenosis or atresia of the external auditory canal.

A foundational knowledge of normal auricular anatomy is essential to understanding the indications for otoplasty. Normal auricular anatomy is as follows:

- Dimensions

- The vertical height of the pinna is 5.5 to 6.5 cm.[8]

- The width of the pinna is approximately 55% of its height, averaging about 35 mm.

- Orientation and proportions

- The apex of the auricle is rotated posteriorly at a 15° angle, aligning the posterior pinna (from the Darwin tubercle to the lobule) parallel to the nasal dorsum.

- The auricle length corresponds to the nose, extending from the eyebrow level to the nasal ala.

- Angles

- The conchomastoid angle (skull to posterior conchal bowl) is approximately 90°.

- The conchoscaphal angle (posterior conchal bowl to scaphoid fossa) is approximately 90°.

- The auriculocephalic angle (skull to helix) is 20° to 30°.[8]

- Helical prominence

- The superior pole is 10 to 12 mm from the mastoid.

- The middle helical rim is 16 to 18 mm.

- The superior lobule is approximately 20 mm.[7]

These measurements guide assessment and correction in otoplasty procedures.

Indications

The indications for otoplasty encompass a wide range of congenital and acquired ear deformities that impact aesthetic appearance and psychosocial well-being. This section outlines the key clinical scenarios in which otoplasty is considered, emphasizing the functional, cosmetic, and psychological motivations for intervention and patient selection criteria to optimize outcomes. Prominauris, the most common indication for otoplasty, occurs when these measurements are noticeably exceeded, typically when the auriculocephalic angle is greater than 30°. The condition is seen in approximately 5% of White individuals and is generally caused by excessive conchal bowl depth and effacement of the antihelix.[9] Prominauris can be inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, and many patients report a family history.

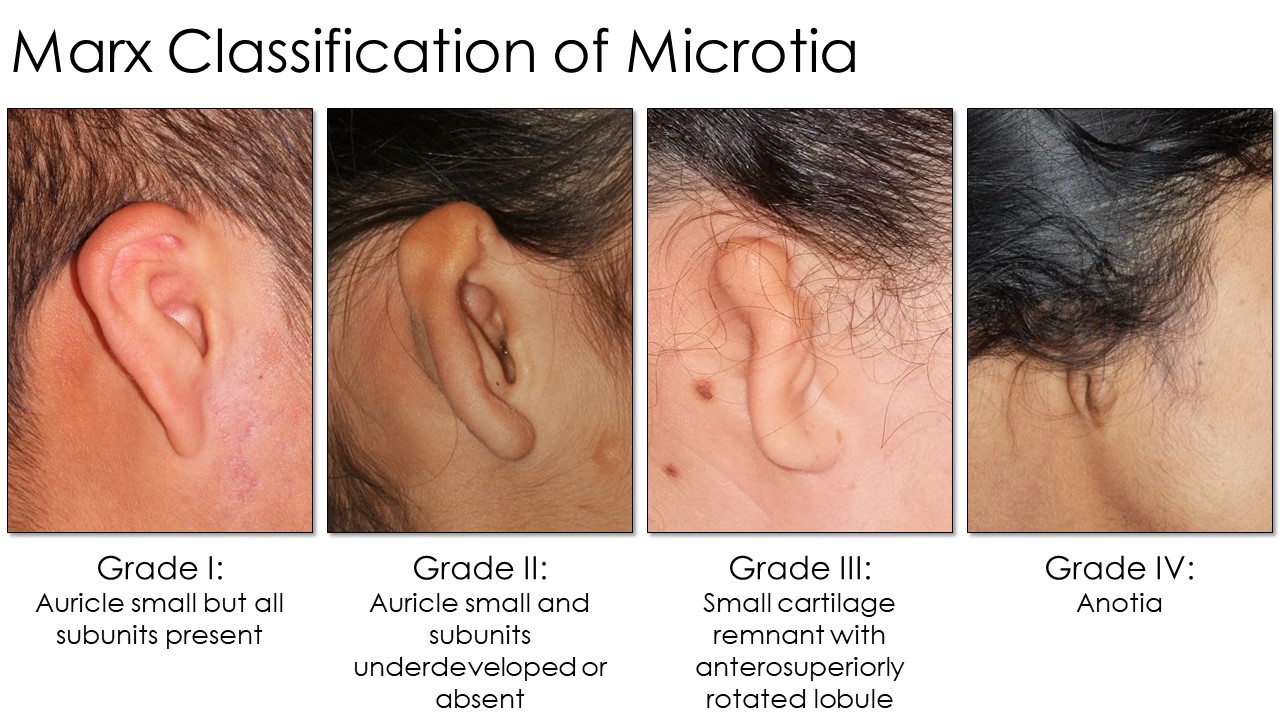

Beyond prominauris, numerous other abnormalities may warrant surgical intervention, including Stahl ear (see Image. Stahl Ear Deformity), cryptotia (see Image. Cryptotia), microtia (see Image. Marx Classification of Microtia), cauliflower ear (see Image. Cauliflower Ear), and many other unnamed deformities. Given that these anomalies do not typically cause hearing loss, intervention is generally performed when the patient can consent to the procedure and is motivated to cooperate with the postoperative care regimen. This typically occurs around the age of 5 to 6, coinciding with when children with auricular deformities may be teased in school and when the auricle has reached 80% to 90% of its adult size. For more complicated reconstructions, however, such as for high-grade microtia, surgeons may wait until the patient reaches age 10 to ensure the development of a sufficient amount of costal cartilage to provide material for grafting.

Contraindications

Contraindications to otoplasty include medical, behavioral, and developmental factors that compromise safety, healing, or surgical outcomes. Active ear infections, uncontrolled chronic conditions like diabetes or hypertension, and coagulopathies increase the risk of complications such as poor wound healing or excessive bleeding. Similarly, patients with unrealistic expectations or body dysmorphic disorder may not benefit, as dissatisfaction often persists despite correction. Caution is also advised for patients unlikely to comply with postoperative care, such as young children prone to wound trauma or intolerance to wearing a headband.

Patients engaging in activities that expose the auricle to trauma, such as contact sports, should defer otoplasty, especially for repairing cauliflower ear deformities. Timing is also critical for specific procedures: microtia reconstruction with autologous costal cartilage should be delayed until the child has grown enough to develop sufficient cartilage for grafting, whereas neonatal ear molding must start within the first 3 weeks of life due to the decreasing malleability of auricular cartilage. Proper patient selection and careful counseling are vital to ensuring safe and effective outcomes.

Equipment

The equipment required for otoplasty for cases of prominauris, Stahl ear, or cryptotia includes:

- Local anesthetic

- Skin marker

- Ruler, measuring tape, or calipers

- #3 Bard-Parker scalpel handle with #15 blade

- Monopolar or bipolar electrocautery

- Suction

- Gauze

- Dissecting scissors: Kaye blepharoplasty, strabismus, or small Metzenbaum

- Forceps: Adson-Brown or 0.5 mm Castroviejo

- Skin hooks: Joseph double prong, 10 mm

- Needle holder: Halsey, Webster, or Castroviejo

- Sutures: 4-0 polyester or polypropylene, 4-0 poliglecaprone, 5-0 plain or chromic gut

- Suture scissors

- Small Penrose or rubber band drain

- Mastoid dressing supplies or Glasscock dressing kit

Additional equipment required for cauliflower ear includes:

- Biopsy punches in various sizes: 3 mm, 4 mm, 5 mm, 6 mm

- Drill with 4 mm and 6 mm cutting and diamond burs

Additional equipment required for microtia includes:

- #10 blade scalpel

- DeBakey forceps

- Weitlaner self-retaining retractors

- Army-Navy retractors

- Freer and Cottle elevators

Personnel

Adult patients may undergo otoplasty for prominauris or Stahl ear under local anesthesia, but most otoplasties require an operating room and general anesthesia. Therefore, a surgical technician and an anesthesia provider would be needed in addition to a surgeon and a nurse. A surgical assistant is also helpful, particularly for more complex cases, such as microtia reconstruction.

Preparation

Before surgery, photographs must be taken of both of the patient's ears for intraoperative reference, regardless of whether the planned procedure is unilateral or bilateral; these should be posted in the operating room during surgery. Measurements should also be obtained, which may include the prominence of the auricles at the superior helix, midhelix, and superior lobule or the location of the auricle relative to a fixed landmark for microtia reconstruction, such as the lateral canthus or the nasal ala.

Preparation for the latter is far more time-consuming than for standard otoplasty, and the preparation necessary will depend on the method selected and the procedure stage. For the first stage, a template of the normal auricle will be needed; this may require nothing more than a tracing with a permanent marker on acetate or x-ray film or may be accomplished with 3-dimensional (3D) printing. The use of 3D printers has revolutionized many aspects of surgery, and the technology can be used in microtia reconstruction for either producing a precise template of the normal ear to facilitate costal cartilage graft harvesting and auricular construct assembly or even to produce a biocompatible implant that mirrors the normal ear.[10][11]

Technique or Treatment

Otoplasty encompasses a variety of surgical techniques designed to correct auricular deformities, improve symmetry, and enhance overall aesthetics while preserving natural appearance and function. These techniques are tailored to address specific deformities, patient anatomy, and aesthetic goals, ensuring individualized care and optimal surgical outcomes.

Anesthesia for Otoplasty

When performed under general anesthesia, injection of epinephrine-containing local anesthetic solution (such as 1% lidocaine with 1:100,000 epinephrine) into the areas of the planned incision and dissection will limit intraoperative bleeding and the need for narcotic administration during surgery. However, care should be taken to avoid injecting large volumes as they can alter the contour of the auricle, particularly when infiltrated into the anterior aspect of the ear. For this reason, measurements of auricular prominence should always be taken before injection of local anesthetic. If the procedure is to be performed under local anesthesia, a circumauricular "diamond" block is used to address the greater auricular, lesser occipital, and auriculotemporal nerves; an additional injection may be required within the conchal bowl near the external auditory meatus to anesthetize the sensory auricular branch of the facial nerve (see Image. Diamond Auricular Block). After injection, the patient's face should be cleansed, exposing both ears and as much of the face as feasible to provide reference points during surgery.

Otoplasty for Prominauris

Standard otoplasty begins with excision of a fusiform section of skin and soft tissue from the posterior aspect of the auricle, centered roughly midway between the helical rim and the postauricular sulcus (see Image. Otoplasty for Prominauris, Part 1). The excision runs from the inferior pole of the conchal bowl to a point roughly 15 mm inferior to the superior helical rim; the width of the excision is approximately 15 to 20 mm, depending on how much prominauris there is and how much skin is likely to be redundant after its reduction. That said, the skin resection will not contribute significantly to the reduction of auricular prominence; attempts to augment the auricular medialization with aggressive skin resection are more likely to result in effacement of the postauricular sulcus.

If Mustardé sutures are planned, a supraperichondrial plane is developed and followed nearly to the helical rim, from the superior pole of the auricle down to the level of the antitragus. If Furnas sutures are to be placed, the same plane is followed posteriorly towards the mastoid. Once the cartilage of the conchal bowl begins to curve anteriorly, the dissection should fall posteriorly, away from the perichondrium, to avoid violating the posterior aspect of the external auditory canal. Upon reaching the mastoid bone, a portion of soft tissue that typically includes the posterior auricular muscle is removed with electrocautery, enough to allow medialization of the conchal bowl, and care is taken to leave the periosteum intact to anchor the Furnas sutures. Due to the division of the posterior auricular muscle, most patients who could wiggle their ears preoperatively will have difficulty wiggling their ears postoperatively.

Attention is then directed to the anterior face of the auricle, where markings are made to guide the placement of the Mustardé sutures (see Image. Otoplasty for Prominauris, Part 1). Various techniques are used for this portion of the procedure, including temporary tattooing with methylene blue dye, placing 1.5-inch 27-gauge hypodermic needles across the antihelix, and passing temporary guide sutures. Guide sutures may be the most effective simulation of the permanent Mustardé sutures that follow them, and this technique will be described.

A monofilament suture, such as a blue 4-0 polypropylene, is thrown in a horizontal mattress configuration between the scaphoid fossa and the conchal bowl, just inferior to the division of the antihelical stem into the superior and inferior crura. The bites are taken perpendicular to the antihelix, avoiding the passage of the needle through the posterior auricular skin. The knot is tied with enough tension to produce the desired folding of the antihelix. An additional 1 or 2 similar horizontal mattresses are placed inferior to the first, not in a straight line, but creating a subtle curve to the antihelix. One more horizontal mattress is also often placed anterosuperior to the first suture to create a superior antihelical crus; the inferior crus is typically already well-formed, even in patients with severe prominauris. Each horizontal mattress should measure roughly 15 mm anteroposteriorly and 10 mm superoinferiorly, with a 2 mm gap between sutures.[2] The permanent sutures can be placed after the guide sutures have been thrown and the antihelix has taken on a satisfactory appearance.

The permanent Mustardé sutures may use the same material as the guide stitches or a different material. However, nylon sutures and polypropylene sutures were associated with a higher risk of extrusion than expanded polytetrafluoroethylene, polydioxanone, and braided polyester in 1 study.[12] Other authors advocate the placement of a dermal graft or a deepithelialized dermofascial flap between the sutures and the skin closure to reduce the risk of further extrusion.[13] From the posterior aspect of the auricle, the permanent sutures are placed as close as possible to the guide sutures, ensuring the needle does not perforate the anterior auricular skin. Because the permanent sutures are placed on the opposite side of the auricle from the guide sutures, they need to be passed perpendicularly to the guide sutures to have the same effect. Each permanent suture should be tightened until the corresponding guide suture begins to lose tension. This mild overcorrection will help maintain the antihelix's desired shape postoperatively.

If necessary, Furnas sutures can be placed (see Image. Otoplasty for Prominauris, Part 2). They should always follow the Mustardé sutures because setting the conchal bowl back first will make access to the posterior aspect of the auricular cartilage more challenging. These sutures are also passed in a horizontal mattress configuration, with bites taken in a superoinferior direction along the most prominent part of the conchal bowl and the mastoid periosteum. Bites taken on the mastoid should be thrown quite posteriorly so that the conchal cartilage is pulled both medially and posteriorly to prevent stenosis of the external auditory canal during the auricular setback.[3] As with the Mustardé sutures, care must be taken to ensure the needle does not perforate the skin of the anterior auricle. Three Furnas sutures are typically required, and it is usually easiest to place all 3 before tying them, carefully modulating the tension in the knots to prevent distortion of the auricular contour as it is medialized. When the mastoid process is prominent, overtightening the Furnas sutures may result in unnatural folding of the conchal bowl between the cymba and cavum conchae.

On occasion, medialization of the auricle has a paradoxical effect on the lobule, causing it to protrude laterally. In these cases, removal of the cauda helicis usually results in a reduction of the auricular prominence. After the procedure, the postauricular incision is closed with an absorbable suture over a small drain, and a mastoid-type pressure dressing is placed. The drain and dressing are removed after 24 hours. For the next 1 to 2 weeks, the patient will wear an athletic headband over the operated ear or ears at all times with infrequent breaks. Following this, the patient will wear the headband at night only for another month. This same regimen is typically followed for otoplasty performed for Stahl ear, cryptotia, and cauliflower ear.

In addition to the cartilage-sparing Mustardé and Furnas methods, numerous other techniques may be added or substituted depending on the surgeon's preference. Davis described the removal of conchal cartilage to augment the setback produced by Furnas sutures. Chongchet advocated accessing the anterior surface of the auricular cartilage to score it and thus better control the creation of the antihelical fold. However, scoring or incising the cartilage predisposes it to develop unnatural-appearing sharp edges, and full-thickness cartilage incisions should be sutured closed whenever possible to prevent this (see Image. Otoplasty for Prominauris, Part 2).[14][15]

Other techniques, including posterior cartilaginous scoring and cartilage rasping, are not employed commonly anymore.[16][17] An important technical development came more recently in the form of "incisionless" otoplasty, developed by Fritsch in 1995, which limits the postauricular exposure to stab incisions to permit placement of buried, percutaneous Mustardé sutures.[18] The technique is not suitable for all patients, with more severe prominauris still requiring an open approach; however, the use of percutaneous sutures eliminates the need for an incision and undermining, thereby decreasing the patient's discomfort, the potential for wound complications, and the need for a drain or pressure dressing.

Otoplasty for Stahl Ear

The Stahl ear deformity is characterized by an unfurling of the superior aspect of the helical rim due to an aberrant antihelical crus (also known as a "Stahl bar") that radiates posterosuperiorly. The unfurling of the helical rim makes the ear appear pointed and elfin, causing the scapha to broaden and flatten. The Stahl bar may occur in addition to the other 2 normal antihelical crura or replace the superior crus. The Stahl ear deformity has been postulated to result from anomalous insertion of the transverse auricular muscle.[19] Regardless of etiology, correction of the malformation is far easier with neonatal ear molding than with otoplasty at a later date.

Because it is more challenging to release a fold from cartilage than to create one, repairing a Stahl ear is less straightforward than the simple placement of Mustardé sutures for antihelical reconstruction. Many techniques for correcting this deformity have been described, from scoring and suturing techniques to wedge excision of the aberrant antihelical crus.[20][21] No consensus exists regarding the best means of addressing the deformity other than performing ear molding in the neonatal period to obviate the need for future surgery.[22] One method of approaching otoplasty for the Stahl ear involves scoring the posterior aspect of the Stahl bar via a postauricular incision to allow it to unroll somewhat, applying the principles advocated by Chongchet for creating an antihelix. If the normal superior crus of the antihelix is absent, placement of Mustardé sutures to create one may also help to efface the Stahl bar.

If scoring is unsuccessful, another option is to excise the cartilage of the Stahl bar, crosshatch, or even section it completely until the pieces lie flat, then replace them with the auricle.[23] Alternatively, the cartilage of the superior auricle may be dissected free of the anterior and posterior skin and folded posteriorly upon itself to act as a splint and flatten the Stahl bar; this technique, however, removes the cartilaginous support from the most superior portion of the auricle.[24] Still, another technique relies upon tension created by the placement of a strip of periosteum to pull the helical rim inwards and flatten the Stahl bar, which seems to work best when accompanied by Mustardé sutures for the creation of a superior antihelical crus.[25]

Otoplasty for Cryptotia

Cryptotia correction focuses on providing the skin necessary to create a postauricular sulcus behind the superior portion of the auricle, which failed to separate from the scalp during fetal development. The simplest means of accomplishing this is to incise along the helical rim and place a skin graft behind the upper pinna. However, an avascular graft can contract and efface the new postauricular sulcus. For this reason, several techniques have been described to transfer skin from the surrounding area.

One such method, described by Dr Kathleen Sie's group at Seattle Children's Hospital, uses a pair of interdigitating trefoil flaps and wide-undermining to transfer half of the skin between the superior aspect of the helical rim and the hairline into a neosulcus obviating the need for a skin graft.[26] Careful flap design and staggered closure of the trefoil points avoid the transfer of hair follicles into the neosulcus and reduce the risk of wound dehiscence (see Image. Cryptotia Reconstruction). Another technique employs a dermofascial kite flap to shift skin from the inferior aspect of the postauricular sulcus into the neosulcus, effectively equating to a vascularized skin graft.[27] With this procedure, a mastoid fascia pedicle containing no named blood vessels is used to perfuse the elliptical skin paddle, which is then rotated into the recipient site.

Microtia Reconstruction

The myriad of modalities described for the repair of microtia employs several different media, from adhesive or magnetic prostheses to off-the-shelf or 3D-printed implants to costal cartilage constructs with temporoparietal fascia flaps and skin grafts.[28][29][30] The specific method must be selected individually, depending on the surgeon's skill set and the patient's wishes, health status, activity level, ability to participate in care, and particular deformity. The severity of microtia is most often described using the Marx classification system, with grade III deformities being the most common to address surgically. Grade I deformities are characterized by auricles at least 2 standard deviations below normal size but still have all the normal auricular subunits. Auricles with grade II deformities are also small, but some subunits are underdeveloped or absent. Grade III deformities consist of minimal auricular cartilage development and a malpositioned lobule, and grade IV deformities have minimal auricular tissue, if any. Grade IV deformities are also known as "anotia" (see Image. Marx Classification of Microtia).[31]

Because reconstruction of large portions of the auricle, or indeed the entire pinna, is often a complex and multistaged operation, it should ideally be undertaken by an interprofessional team with extensive experience with the relevant techniques and a high volume of patients. However, the approaches employed for microtia repair are broadly applicable and are also used for reconstructing oncologic, burn, and traumatic tissue defects.[32] For a detailed description of the procedures used in microtia reconstruction, please see 'Ear Microtia' by J Andrews et al.[31]

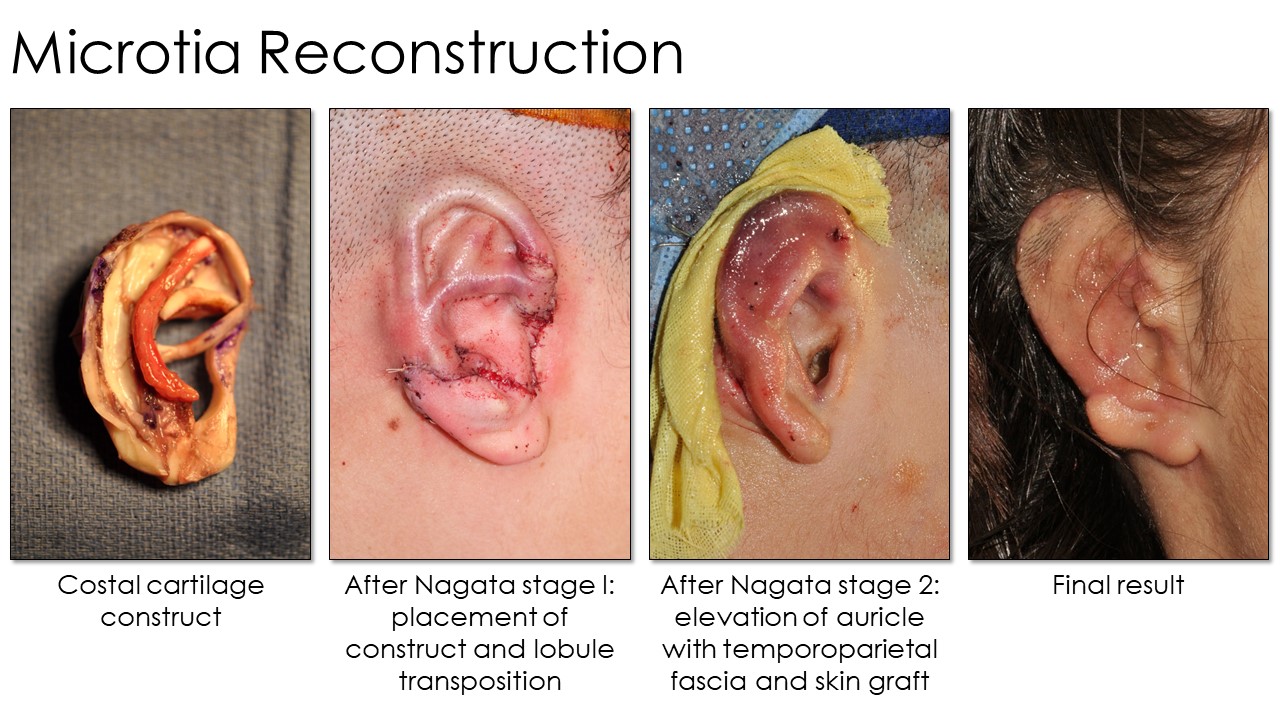

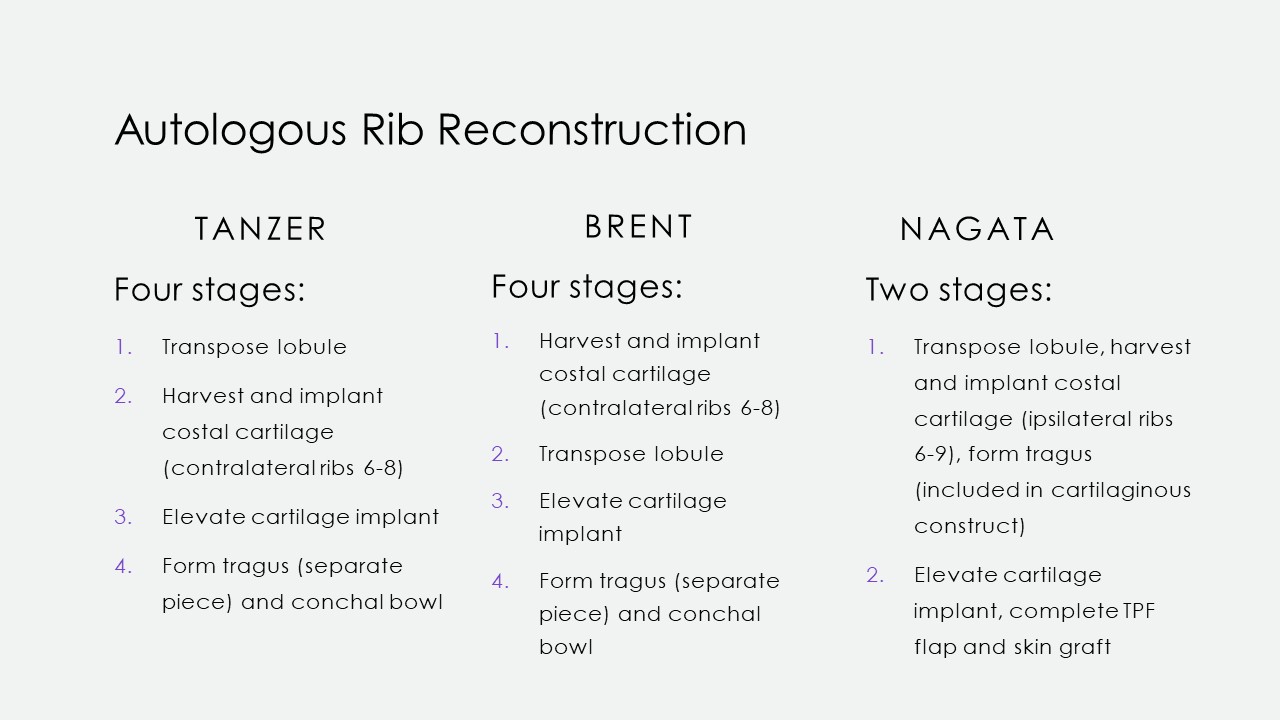

Briefly, surgical repair of microtia requires the placement of an auricular construct to replace the missing cartilage and to provide a scaffold upon which skin and soft tissue can be draped to form a neoauricle. This scaffold may be synthetic—polyethylene, polycaprolactone, or other materials—or autologous, usually costal cartilage. Tanzer's and Brent's early descriptions of costal cartilage-based microtia repair required 4 procedures: creation and placement of an auricular scaffold, transposition of the lobule, elevation of the construct, and creation of a tragus (see Image. Microtia Rib Reconstruction Techniques).[4][33] Further technical refinement resulted in consolidation of the operation into 2 stages, which can be employed for either reconstruction with costal cartilage (Nagata method) or with an implanted prosthesis (Reinisch method): placement of the construct (including a tragus) and transposition of the lobule, and later elevation of the construct (see Image. Microtia Reconstruction).[5][34] In 2022, however, microtia reconstruction took a massive technological leap forward with the first use of cell bioprinting to produce an autologous construct without the need for costal cartilage.[35]

Otoplasty for Cauliflower Ear

The surgical technique selected for a patient with a cauliflower ear deformity will depend primarily upon the extent and location of the cartilage fibrosis within the auricle and the degree of skin and soft tissue contraction, if any. The fibrocartilage may be sculpted into a normal or near-normal contour with a scalpel or curettes for mild to moderate deformities that alter the auricle's contours but not the pinna's outline. In long-standing deformities, particularly with older patients, the fibrocartilage may develop calcification within it, necessitating an otologic drill (see Image. Surgical Repair of Cauliflower Ear). If only the conchal cartilage is affected, it can generally be resected entirely without any adverse impact on the appearance or the support of the auricle. The incisions used for surgical exposure may be located at the junction of the antihelix and conchal bowl for access to the concha or along the medial edge of the helical rim for access to the scaphoid fossa and antihelix.

A postauricular approach may also be employed, as it is used for otoplasty for prominauris, which will provide access to the helix itself. In many cases, correction of helical rim distortion may be achieved by simply incising along the medial aspect of the helical cartilage, which releases the tension that developed during scar contracture. After the abnormal cartilage is resected or reshaped, Mustardé or Furnas sutures may be required to normalize the auricular contour further.[36] For more severe deformities, either with extensive cartilage destruction or soft tissue contracture, postauricular skin flaps or reconstruction with contralateral conchal cartilage, nasal septal cartilage, or costal cartilage may be needed, following the principles described above for microtia reconstruction.[37] Most importantly, otoplasty for the cauliflower ear is generally deferred until the patient has ceased participating in activities that are liable to result in auricular trauma. For a detailed description of the procedures used in cauliflower ear reconstruction, please see 'Cauliflower Ear' by BC Patel et al.[38]

Nonsurgical Ear Molding

Applying external splints to a congenitally malformed ear over 4 to 6 weeks gives a more than 90% chance of producing substantial improvement or even a normal auricular contour if the patient is selected appropriately.[39] Because effective ear molding requires a sufficiently high level of maternal estrogens to keep the elastic cartilage of the auricle malleable present, the treatment course should ideally begin by 3 weeks of age. Commercially available ear molding systems typically consist of a silastic cradle that adheres to the skin around the ear and supports the retractors or conformers subsequently placed to contour the auricle appropriately. An outer cover is then applied to the cradle to stabilize the device (see Image. Ear Molding).

Hair trimming and application of skin adhesive will improve the chance of the appliance remaining in place for the requisite 2 weeks until the first follow-up visit when the device is removed and the ear examined for progress. Ordinarily, a larger appliance is then placed due to the patient's interim growth, and another follow-up appointment is made 2 weeks later. This sequence repeats until the desired results are obtained or no further progress is made, usually over about 6 weeks. Satisfaction rates are very high, and the only likely complications are irritation from the adhesive and abrasions or pressure ischemia from the retractors and conformers.

Complications

Complications of otoplasty are categorized as early or late. Early complications typically stem from wound healing problems, while late complications generally reflect structural issues.

Early Complications

The most concerning early complication after otoplasty is the development of a hematoma, which, if left untreated, may result in a wound infection, perichondritis, or cartilage necrosis. Any of these conditions may lead to cartilage resorption or even fibrosis, leading to a cauliflower ear deformity. For this reason, a small drain and a pressure dressing are typically left in place postoperatively for 24 to 48 hours. However, the pressure dressing may cause skin necrosis if applied too tightly. Increasing pain over the first 24 to 72 hours after surgery should prompt concern for a hematoma and removal of the dressing for examination. While trauma to the ear in the early postoperative period may cause a hematoma or even rupture of a critical contouring suture, most hematomas result from transient blood pressure increases and inadequate hemostasis. Significant asymmetry of auricular edema and ecchymosis in the first 24 to 48 hours, particularly with fluctuance and fever, indicate that aspiration or even opening the incision to evacuate the fluid may be necessary.

Development of auricular pain, erythema, and edema more than 2 to 3 days after surgery is more likely to indicate perichondritis than hematoma, particularly if the erythema and edema spare the lobule, where there is no cartilage (see Image. Postoperative Perichondritis). Patients who develop postoperative perichondritis or chondritis should receive either oral or intravenous antibiotics, depending on the severity of the infection and the rapidity with which it responds initially. The most common pathogen isolated is Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which is best treated with fluoroquinolone, such as ciprofloxacin, even in pediatric cases.

In microtia reconstruction, skin and cartilage necrosis most frequently arise in the area of the superior helix, where pressure and tenuous perfusion may result in wound dehiscence. However, infection with Pseudomonas may also occur. These complications are typically addressed with the transposition of a temporoparietal fascia flap, which restores a healthy blood supply and provides a vascularized bed for skin grafting and any needed antibiotics.

Late Complications

The most common late complication of otoplasty is dissatisfaction with the cosmesis of the operated ear or ears.[7] This can occur for several reasons, from failure to set the left and right auricular prominences within a 3 mm margin of error to misplacement of sutures that results in contour abnormalities or insufficient reduction of auricular prominence. Common examples include the "hidden helix" deformity, in which overtightening of the Mustardé sutures results in an antihelical prominence greater than that of the helix; this appears unnatural because the helix is not visible from a frontal view. Misplacement of the Mustardé sutures may also cause a "vertical post" deformity, in which the antihelix becomes an unnaturally straight vertical ridge rather than assuming the gentle curvilinear contour that it would normally have.

The "telephone ear" deformity results from excessive tightening of the central Furnas suture relative to the superior and inferior sutures, which causes the superior and inferior poles of the auricle to bow outward and resemble the curve of a corded telephone handset. Less commonly, the telephone ear deformity may also be caused by excessive cartilage resection from the central aspect of the conchal bowl, thus permitting a disproportionate setback of the central concha. The reverse telephone ear deformity, on the other hand, occurs when the superior and inferior Furnas sutures are tied too tightly relative to the central suture. Incorrect orientation of the Furnas sutures may pull the auricle anteriorly, which can cause compression of the cartilaginous portion of the external auditory meatus, resulting in conductive hearing loss if the malposition is severe.

When all of the sutures are placed properly, and the prominence of the auricle is reduced, but the lobule does not medialize accordingly, the resulting appearance is known as an "outstanding lobule." This is most effectively corrected by removing the cartilaginous cauda helicis, which is typically the structure that continues to press the lobule laterally, even after medialization of the pinna. Suppose a deformity becomes apparent once the postoperative edema has subsided and the headband is no longer being worn. In that case, corrective surgery should be undertaken sooner rather than later, as progressive scar development may affect the ease with which the revision is performed.

Unique to microtia reconstruction is the set of late complications that can occur with an auricular construct. Trauma to the reconstructed auricle, whether cartilaginous or synthetic, can result in skin necrosis and implant exposure with subsequent resorption—if costal cartilage was used—or infection. Even without external trauma, implant migration, and extrusion are risks as well. However, implant exposure and extrusion rates are lower with costal cartilage constructs than with porous polyethylene.[28]

Other Types of Complications

Beyond ear-specific complications, more common adverse outcomes may also occur after otoplasty. These include prolonged tenderness or hypersensitivity, suture extrusion, and unsightly scarring. Chronic pain or tenderness usually resolves spontaneously, although it may take months or even years to do so, and there may be a higher incidence of this complication when anterior scoring techniques are used.[40] When sutures extrude, they can generally be removed without any change in the contour of the auricle, as after a few weeks, the scar holds the cartilage in its postoperative form more than the sutures. As the majority of otoplasty is performed via postauricular incisions, mild to moderate scarring does not generally pose a problem; however, patients prone to keloid development may suffer this complication after surgery. Similarly, auricular cartilage is prone to fibrosis when traumatized, and some patients may develop a cauliflower ear deformity postoperatively, particularly after correction of a prior cauliflower ear deformity.

Clinical Significance

Otoplasty is a critical skill for plastic surgeons, otolaryngologists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, and facial plastic surgeons. Restoring a normal appearance to an ear can significantly impact a patient's quality of life, whether correcting a lop ear deformity, a cauliflower ear, or microtia.[36][41][42] In the case of minor congenital auricular anomalies, early initiation of ear molding is critical. Beyond 2 to 3 weeks of age, patients with auricular deformities typically need to wait until at least the age of 5 or 6 to pursue surgery. Standard otoplasty with Furnas and Mustardé sutures for prominauris is offered by many plastic surgeons, otolaryngologists, oral and maxillofacial surgeons, and facial plastic surgeons. Still, more elaborate procedures, such as reconstruction of microtic ears or correction of cauliflower ear deformity, should only be undertaken by surgeons experienced with the necessary techniques due to their complexity and propensity to develop complications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Otoplasty requires a collaborative, patient-centered approach to optimize outcomes and ensure safety. Clinicians and surgeons must possess advanced knowledge of auricular anatomy and master surgical techniques to tailor otoplasty procedures to each patient’s unique anatomy and aesthetic goals. Preoperative strategies include thorough patient assessment, setting realistic expectations, and detailed surgical planning. Nurses and advanced clinicians play a key role in pre and postoperative education, ensuring patients and families understand the procedure, recovery process, and signs of complications such as infection or hematoma. Pharmacists contribute by advising on perioperative medication management, including pain control and infection prevention strategies.

Interprofessional communication and care coordination are vital to maintaining a cohesive team effort. Effective communication among the surgical team, anesthesiologists, and nursing staff ensures smooth intraoperative procedures and immediate postoperative care. Care coordination extends to outpatient follow-up, where nurses monitor wound healing and reinforce education while clinicians evaluate surgical outcomes and address patient concerns. By fostering collaboration, leveraging each team member's expertise, and prioritizing patient-centered care, health professionals can enhance patient satisfaction, safety, and overall surgical success in otoplasty.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Auricle Surface Anatomy. This image shows the ear auricle's parts, parts, including the helix and its crus, the antihelix and its superior and inferior crura, the Darwin tubercle, triangular and scaphoid fossae, the tragus, conchal cymba and cavum, the intertragal incisura, antitragus, and lobule.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Cranial Surface of the Right Auricular Cartilage. This illustration demonstrates the cranial surface of the right external ear, including the spina helicis, sulus antihelicis transversus, eminentia conchae, ponticulus, cauda helicis, and the cartilage of meatus.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Surgical Repair of Cauliflower Ear. A) Preoperative view. Note the anterior malposition of the helical rim and the excess bulk within the scaphoid fossa. B) The auricular skin is elevated off the underlying cartilage anteriorly and posteriorly via an incision at the junction of the helix and scapha. The perichondrium is scarred and does not elevate easily. C) The skin flaps are replaced, and a quilting suture is passed after reshaping the cartilage with a scalpel, a curette, and a drill. D) Postoperative view at 1 month.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Diamond Auricular Block. The dashed lines represent injections posterior to the auricle, and the X indicates a conchal bowl injection to anesthetize the sensory auricular branch of the facial nerve. The diamond block anesthetizes the auriculotemporal, lesser occipital, and greater auricular nerves, providing complete anesthesia of the auricle.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Cryptotia Reconstruction. A) Modified trefoil technique with red lines indicating skin flap incisions. B-F) Kite flap technique: B) Flap marked with parallel lines for fascial pedicle placement. C) Postauricular incision and flap elevation completed. D) Flap transposed into superior postauricular incision. E) Neosulcus created with flap inset. F) Final result shows improved superior helical definition compared to image A.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Otoplasty for Prominauris, Part 1. A) Measurement of the prominent auricle is taken at the superior, posterior, and inferior aspects of the helix. Note the last of superior antihelical crus. B) The postauricular skin ellipse is excised. C) Supraperichondrial sharp dissection is done to expose the helical rim. D) Cautery is used to dissect and remove supraperiosteal soft tissue on the mastoid process. E) Placement of horizontal mattress guide sutures to define the antihelix and superior crus. F) Mustardé sutures are placed.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Otoplasty for Prominauris, Part 2. G) Partial thickness resection of the conchal cartilage, using the Davis technique, is performed. H) Placement of the first bite of the Furnas horizontal mattress sutures into the conchal cartilage is shown. I) Placement of the second bite of the Furnas horizontal mattress suture into the mastoid periosteum is shown. J) Resection of the cauda helicis to reduce the prominence of the lobule is shown. K) This shows closure with gut suture over a rubber band drain. L) This is the final result. Note the improved antihelical definition and reduced auricular prominence.

Contributed by MH Hohman, MD, FACS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Sensory Areas of the Head. This illustration shows the general distribution of the 3 divisions of the trigeminal nerve in the scalp, face, and neck.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

The Muscles of the Ear. This illustration shows the extrinsic and intrinsic muscles of the ear. The extrinsic are the auricularis superior, auricularis anterior, and auricularis posterior. The intrinsic muscles are the tragicus, antitragicus, helicis minor, helicis major, and the oblique and transverse.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Veins of the Scalp. This illustration shows the venous drainage of the scalp, including the supratrochlear and supraorbital veins, the temporal veins and their branches, the posterior auricular vein, and the occipital vein and its branches.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Arteries of the Head and Face. This illustration shows the arteries of the head and face, including the arterial supply to the ear, which consists of the superficial temporal artery anteriorly and the posterior auricular and lesser occipital arteries posteriorly—all branches of the external carotid system.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Byrd HS, Langevin CJ, Ghidoni LA. Ear molding in newborn infants with auricular deformities. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2010 Oct:126(4):1191-1200. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e617bb. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20453717]

MUSTARDE JC. The correction of prominent ears using simple mattress sutures. British journal of plastic surgery. 1963 Apr:16():170-8 [PubMed PMID: 13936895]

Furnas DW. Correction of prominent ears by conchamastoid sutures. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1968 Sep:42(3):189-93 [PubMed PMID: 4878456]

Brent B. Auricular repair with autogenous rib cartilage grafts: two decades of experience with 600 cases. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1992 Sep:90(3):355-74; discussion 375-6 [PubMed PMID: 1513882]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNagata S. A new method of total reconstruction of the auricle for microtia. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1993 Aug:92(2):187-201 [PubMed PMID: 8337267]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVeugen CCAFM, Dikkers FG, de Bakker BS. The Developmental Origin of the Auricula Revisited. The Laryngoscope. 2020 Oct:130(10):2467-2474. doi: 10.1002/lary.28456. Epub 2019 Dec 11 [PubMed PMID: 31825094]

Schneider AL, Sidle DM. Cosmetic Otoplasty. Facial plastic surgery clinics of North America. 2018 Feb:26(1):19-29. doi: 10.1016/j.fsc.2017.09.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29153186]

Janz BA, Cole P, Hollier LH Jr, Stal S. Treatment of prominent and constricted ear anomalies. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2009 Jul:124(1 Suppl):27e-37e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aa0e9d. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19568137]

Salgarello M, Gasperoni C, Montagnese A, Farallo E. Otoplasty for prominent ears: a versatile combined technique to master the shape of the ear. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2007 Aug:137(2):224-7 [PubMed PMID: 17666245]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKoento T, Damara FA, Reksodiputro MH, Safitri ED, Anatriera RA, Widodo DW, Dewi DJ. The utilization of three-dimensional imaging and three-dimensional-printed model in autologous microtia reconstruction. Annals of medicine and surgery (2012). 2024 May:86(5):2926-2934. doi: 10.1097/MS9.0000000000001976. Epub 2024 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 38694346]

Kim M, Kim YJ, Kim YS, Roh TS, Lee EJ, Shim JH, Kang EH, Kim MJ, Yun IS. One-Year Results of Ear Reconstruction with 3D Printed Implants. Yonsei medical journal. 2024 Aug:65(8):456-462. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2023.0444. Epub [PubMed PMID: 39048321]

Raposo A, Calero J, Guilllén A, Giribet A, Barrios A, García-Purriños F. Suture material utilised influences suture extrusion rate in otoplasty: A non-randomised retrospective single-centre study. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2019 Sep:72(9):1576-1606. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2019.05.028. Epub 2019 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 31153812]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBulstrode NW, Ronde EM, Mazeed AS. Further Refinements in Otoplasty Surgery: A Modified Approach to Prevent Suture Extrusion in Cartilage-Suturing Otoplasty Using a Postauricular Dermofascial Flap. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2024 Dec 1:154(6):1191e-1199e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000011342. Epub 2024 Feb 7 [PubMed PMID: 38954644]

Naumann A. Otoplasty - techniques, characteristics and risks. GMS current topics in otorhinolaryngology, head and neck surgery. 2007:6():Doc04 [PubMed PMID: 22073080]

CHONGCHET V. A METHOD OF ANTIHELIX RECONSTRUCTION. British journal of plastic surgery. 1963 Jul:16():268-72 [PubMed PMID: 14042756]

CONVERSE JM, NIGRO A, WILSON FA, JOHNSON N. A technique for surgical correction of lop ears. Plastic and reconstructive surgery (1946). 1955 May:15(5):411-8 [PubMed PMID: 14384519]

STENSTROEM SJ. A "NATURAL" TECHNIQUE FOR CORRECTION OF CONGENITALLY PROMINENT EARS. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1963 Nov:32():509-18 [PubMed PMID: 14078273]

Fritsch MH. Incisionless otoplasty. The Laryngoscope. 1995 May:105(5 Pt 3 Suppl 70):1-11 [PubMed PMID: 7760682]

Petersson RS, Friedman O. Current trends in otoplasty. Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2008 Aug:16(4):352-8. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0b013e328304b40d. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18626255]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhan MA, Jose RM, Ali SN, Yap LH. Correction of Stahl ear deformity using a suture technique. The Journal of craniofacial surgery. 2010 Sep:21(5):1619-21. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3181ef2f0c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20856059]

Kaplan HM, Hudson DA. A novel surgical method of repair for Stahl's ear: a case report and review of current treatment modalities. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1999 Feb:103(2):566-9 [PubMed PMID: 9950546]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePanopoulou G, Petrou I, Vassiliou A. Nonsurgical Correction of Stahl's Ear in Neonates: A Case Study. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2022 Oct:10(10):e4566. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004566. Epub 2022 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 36246079]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNoguchi M, Matsuo K, Imai Y, Furuta S. Simple surgical correction of Stahl's ear. British journal of plastic surgery. 1994 Dec:47(8):570-2 [PubMed PMID: 7697286]

Liu L, Pan B, Lin L, Yu X, Yang Q, Zhao Y, Zhuang H, Jiang H. A new method to correct Stahl's ear. Journal of plastic, reconstructive & aesthetic surgery : JPRAS. 2011 Jan:64(1):48-52. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.03.056. Epub 2010 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 20462821]

Nakayama Y, Soeda S. Surgical treatment of Stahl's ear using the periosteal string. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 1986 Feb:77(2):222-6 [PubMed PMID: 3945685]

Adams MT, Cushing S, Sie K. Cryptotia repair: a modern update to the trefoil flap. Archives of facial plastic surgery. 2011 Sep-Oct:13(5):355-8. doi: 10.1001/archfacial.2011.60. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21931091]

Simon F, Celerier C, Garabedian EN, Denoyelle F. Mastoid fascia kite flap for cryptotia correction. International journal of pediatric otorhinolaryngology. 2016 Nov:90():210-213. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2016.09.032. Epub 2016 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 27729135]

Hohman MH, Lindsay RW, Pomerantseva I, Bichara DA, Zhao X, Johnson M, Kulig KM, Sundback CA, Randolph MA, Vacanti JP, Cheney ML, Hadlock TA. Ovine model for auricular reconstruction: porous polyethylene implants. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2014 Feb:123(2):135-40. doi: 10.1177/0003489414523710. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24574469]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaluch N, Nagata S, Park C, Wilkes GH, Reinisch J, Kasrai L, Fisher D. Auricular reconstruction for microtia: A review of available methods. Plastic surgery (Oakville, Ont.). 2014 Spring:22(1):39-43 [PubMed PMID: 25152646]

Rodríguez-Arias JP, Gutiérrez Venturini A, Pampín Martínez MM, Gómez García E, Muñoz Caro JM, San Basilio M, Martín Pérez M, Cebrián Carretero JL. Microtia Ear Reconstruction with Patient-Specific 3D Models-A Segmentation Protocol. Journal of clinical medicine. 2022 Jun 22:11(13):. doi: 10.3390/jcm11133591. Epub 2022 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 35806875]

Andrews J, Kopacz AA, Hohman MH. Ear Microtia. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 33085390]

Firmin F, Marchac A. [Reconstruction of the burned ear]. Annales de chirurgie plastique et esthetique. 2011 Oct:56(5):408-16. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2011.07.009. Epub 2011 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 21937159]

TANZER RC. Total reconstruction of the external ear. Plastic and reconstructive surgery and the transplantation bulletin. 1959 Jan:23(1):1-15 [PubMed PMID: 13633474]

Reinisch JF, Lewin S. Ear reconstruction using a porous polyethylene framework and temporoparietal fascia flap. Facial plastic surgery : FPS. 2009 Aug:25(3):181-9. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1239448. Epub 2009 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 19809950]

Prabhakaran P, Palaniyandi T, Kanagavalli B, Ram Kumar V, Hari R, Sandhiya V, Baskar G, Rajendran BK, Sivaji A. Prospect and retrospect of 3D bio-printing. Acta histochemica. 2022 Oct:124(7):151932. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2022.151932. Epub 2022 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 36027838]

D'Ascanio L, Gostoli E, Ricci G, De Luca P, Latini G, Brenner MJ, Di Stadio A. Modified Valente Technique for Cauliflower Ear: Outcomes in Children at Two-Year Follow-Up : New Surgical Technique for Cauliflower Ear. Aesthetic plastic surgery. 2024 May:48(10):1906-1913. doi: 10.1007/s00266-024-03914-5. Epub 2024 Mar 18 [PubMed PMID: 38499875]

Putri IL, Bogari M, Khoirunnisa A, Dhafin FR, Kuswanto D. Surgery of Severe Cauliflower Ear Deformity. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. Global open. 2023 Apr:11(4):e4953. doi: 10.1097/GOX.0000000000004953. Epub 2023 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 37091928]

Patel BC, Hohman MH, Hutchison J, Hatcher JD. Cauliflower Ear. StatPearls. 2025 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29261905]

Daniali LN, Rezzadeh K, Shell C, Trovato M, Ha R, Byrd HS. Classification of Newborn Ear Malformations and their Treatment with the EarWell Infant Ear Correction System. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2017 Mar:139(3):681-691. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000003150. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28234847]

van Wingerden JJ, van Nieuwenhoven CA. Ear pain following prominent ear surgery: an observation. Annals of plastic surgery. 2006 Oct:57(4):479-80 [PubMed PMID: 16998354]

Carvalho C, Marinho AS, Barbosa-Sequeira J, Correia MR, Banquart-Leitão J, Carvalho F. Quality of life after otoplasty for prominent ears in children. Acta otorrinolaringologica espanola. 2023 Jul-Aug:74(4):226-231. doi: 10.1016/j.otoeng.2022.11.004. Epub 2022 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 36427795]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceVijverberg MA, Hol MKS, Reinisch JF. Assessment of cost and Health-Related quality of life following three different methods of microtia reconstruction in 30 patients. Clinical otolaryngology : official journal of ENT-UK ; official journal of Netherlands Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology & Cervico-Facial Surgery. 2021 Jul:46(4):850-853. doi: 10.1111/coa.13730. Epub 2021 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 33533194]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence