Introduction

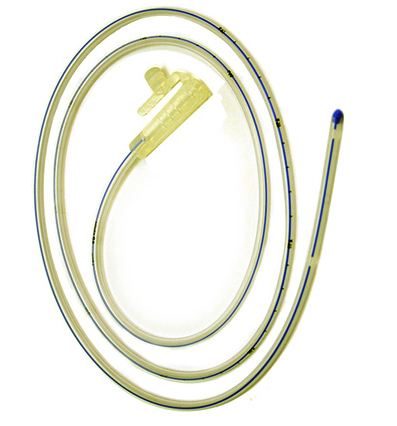

As one might surmise from their name, Nasogastric tubes are tubes inserted through the nares to pass through the posterior oropharynx, down the esophagus, and into the stomach. Dr. Abraham Levin first described their use in 1921 (see Image. Nasogastric Tube). Nasogastric tubes are typically used for decompression of the stomach in intestinal obstruction or ileus. Still, they can also be used to administer nutrition or medication to patients who cannot tolerate oral intake.[1][2] Depending on the intended purpose of the tube, there are different types, each specifically designed for its use.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The nares are the anterior opening of the nasal sinuses. 5 to 7 cm posterior to the nares, the nasal sinus connects to the nasopharynx, which is continuous with the oropharynx. The pharynx's length from the skull's base to the esophagus's start is 12 to 14 cm. The esophagus starts at the upper esophageal sphincter, the cricopharyngeus, and runs down through the diaphragm to the stomach for a length of approximately 25 cm. While the stomach is a highly distensible structure and, therefore, can vary in length, the empty stomach is generally around 25 cm long. Thus, if one intended to place a tube through the nares and place it in the middle of the stomach, approximately 55 cm of the tube should be inserted.[3]

Several methods estimate the depth at which an NG should be placed. All estimation methods have some margin of error.[4] A common pre-procedure maneuver is to loop the tube over 1 of the patient’s ears, place the tip at the patient’s xiphoid process, and estimate the length of the tube that should be inserted.[5]

Indications

The most common indication for placing a nasogastric tube is to decompress the stomach in the setting of distal obstruction. Small bowel obstruction from adhesions or hernias, ileus, obstructing neoplasms, volvulus, intussusception, and many other causes may block the normal passage of bodily fluids such as salivary, gastric, hepatobiliary, and enteric secretions.[2] These fluids build up, causing abdominal distension, pain, and nausea. Eventually, the fluids build up enough that nausea progresses to emesis, putting the patient at risk for aspiration, an event with mortality as high as 70% depending on the volume of fluid aspirated. Similarly, intractable nausea or emesis, whether caused by medications, intoxication, or other reasons, can be an indication for the placement of a nasogastric tube to prevent aspiration. Prophylactic placement of NG tubes in patients with abdominal surgery is not recommended. Patients who develop postoperative ileus tend to recover faster without the placement of an NG tube.[6]

Less commonly, nasogastric tubes can be placed to administer medications or nutrition in patients with a functional gastrointestinal tract but cannot tolerate oral intake. This is most common in patients who have suffered a stroke or other malady which has left them unable to swallow effectively.[3] Nasogastric tubes may be placed for nutritional support while waiting to see how much function the patient recovers. Suppose the patient does not recover their swallowing ability or otherwise requires long-term nutritional support. In that case, a more permanent feeding tube, such as a gastrostomy or jejunostomy feeding tube, should be placed.

NG tubes have been used for various reasons in patients with GI bleeding. In the past, NG lavage was thought to help control GI bleeding. However, recent studies have shown that this is not helpful.[7] Another indication for the placement of a nasogastric tube is in the setting of massive hematochezia. Given that an upper GI bleed causes up to 15% of massive hematochezia, placement of a nasogastric tube after initiating resuscitation may potentially aid in diagnosis. Of note, an upper GI source of bleeding is only ruled out after aspiration of gastric contents from a nasogastric tube if the fluid is bile-tinged. If the fluid is not bile-tinged, it is possible that a duodenal ulcer has caused bleeding but also scarred the pylorus, causing a gastric outlet obstruction, which prevents the blood from aspirating from the stomach.[8] However, the placement of an NG tube has not been shown to improve patient outcomes in patients with GI bleed.[9]

Contraindications

The most common contraindication to the placement of nasogastric tubes is if there is significant facial trauma or basilar skull fractures. In these cases, attempted placement of a tube via the nares may exacerbate the existing trauma. In rare cases, nasogastric tubes have even been placed into the skull in the setting of basilar skull fractures.[10] Esophageal trauma is also a potential contraindication, especially in the setting of ingestion of caustic substances, where the placement of a nasogastric tube may create or worsen perforations. Esophageal obstruction, such as with a neoplasm or foreign object, is an obvious contraindication to nasogastric tube placement. Anticoagulation is a relative contraindication as the trauma from tube placement may cause bleeding. For patients with previous gastric bypass surgery, hiatal hernia repair, or abnormal GI anatomy, NG tubes should be placed under endoscopy.[11]

Equipment

Since there are several nasogastric tube types, selecting the correct tube is the most important part of gathering equipment. For decompression, the standard tube used is a double-lumen nasogastric tube. There is a double-one large lumen for suction and 1 smaller lumen to act as a sump. A sump allows air to enter so the suction lumen does not become adherent to the gastric wall or obstructed when the stomach fully collapses.

If the tube is being placed for administering medications or nutrition, then a small-bore single-lumen tube such as a Dobhoff or Levin tube may be placed. A Levin tube is just a simple small-diameter tube. A Dobhoff is a small-diameter tube with a weight on the end. The weight is added in hopes that gravity and peristalsis advance the end of the tube past the pylorus, given an additional barrier between the nutrition or medications administered and any potential aspiration risk.

Additional essential equipment is some type of sterile lubricating gel to dip the tube into to ease its passage through the sinus cavity, as well as gloves to protect the patient and whoever is placing the tube. The gloves do not have to be sterile, as this is a nonsterile procedure.

Non-essential, helpful equipment is a cup of water with a straw in it for the patient to sip from during the procedure, provided they can tolerate it. This swallowing action helps advance the tube, and the water can ease some irritation on the back of the oropharynx from the tube. The topical use of local anesthetics such as lidocaine is not very useful.[12][13] However, there is evidence that nebulized lidocaine relieves discomfort and increases the chance of NG tube placement.[14] Having a basin nearby in case the patient has an episode of emesis during the procedure is also advisable.

Personnel

While an experienced provider can place a tube by themselves, having an assistant nearby can be helpful in case extra supplies, such as a basin, need to be obtained during the placement procedure if the patient begins to have emesis.

Preparation

The indication for the procedure, potential complications, and alternative to treatment should be explained to the patient, and an informed consent form should be signed. The patient should be placed in the sitting position if possible. Some sort of protective sheet should be placed on the patient’s chest in case they have an episode of emesis during the procedure. The nasogastric tube should be connected to the suction tubing, and the suction tubing should be connected to a suction bucket before tube placement to minimize the risk of spillage of gastric contents. All supplies should be close at hand to minimize unnecessary movement during the procedure.

Technique or Treatment

The individual placing the tube should put on nonsterile gloves and lubricate the tip of the tube (see Image. Nasogastric tube Tip Encircled). A common error when placing the tube is to direct it upward as it enters the nares; this causes the tube to push against the top of the sinus cavity and cause increased discomfort. The tip should instead be directed parallel to the floor, directly toward the back of the patient's throat. At this time, the patient can be given a cup of water with a straw to sip from to help ease the passage of the tube. The tube should be advanced with firm, constant pressure while the patient sips. If there is a great deal of difficulty in passing the tube, a helpful maneuver is to withdraw the tube and attempt again after a short break in the contralateral nares, as the tube may have become coiled in the oropharynx or nasal sinus. In intubated patients, reverse Sellick's maneuver (pulling the thyroid cartilage up rather than pushing it down during intubation) and freezing the NG tube may help facilitate the tube placement.[15] Once the tube has been inserted appropriately, typically around 55 cm, as previously noted, it should be secured to the patient's nose with tape.[16]

Once the tube has been advanced to the estimated necessary length, the correct location is often made obvious by aspirating a large amount of gastric contents. Pushing 50 cc of air through the tube using a large syringe while auscultating the stomach with a stethoscope is a commonly described maneuver to determine the tube's location, but it is of questionable efficacy.[17][18] Misplaced NG tubes in the left mainstem and small bowel can sound similar to adequately placed NG tubes. Taking an abdominal x-ray is the best way to confirm the location of the tube, even if there is the aspiration of gastric contents, as the tube may be placed past the pylorus where it aspirates not just gastric secretions but also hepatobiliary secretions, leading to persistently high output even when the patient's acute issue has resolved. If feeding is planned through the tube, then it is imperative to confirm its location, as placing feeds into the lungs can cause potentially fatal complications. The ideal location for an NG tube placed for suction is within the stomach because placement past the pylorus can cause damage to the duodenum. The ideal location for an NG feeding tube is postpyloric to decrease the risk of aspiration.

The removal of an NG tube is usually a simple procedure. However, the tube should not be forcefully removed as it can become knotted.[19]

Complications

The most common complications related to the placement of nasogastric tubes are discomfort, sinusitis, or epistaxis, all of which typically resolve spontaneously with the removal of the nasogastric tube. As noted previously in the contraindications, nasogastric tubes may cause or worsen a perforation in the setting of esophageal trauma, particularly after caustic ingestion, where extreme caution must be used if the placement is attempted. Blind placement of the tube in patients with injury to the cribriform plate may lead to intracranial placement of the tube.[20] The intragastric placement must be confirmed if the tube is being placed for administering medications or nutrition. Introducing medication or tube feeds to the lungs can cause major complications, including death.[2] Even in intubated patients, the NG tube can still be accidentally placed into the airway.[21] Another complication that all those managing nasogastric tubes should be aware of is specifically for the double-lumen nasogastric tubes. These large diameter tubes stent the lower and upper esophageal sphincter open while in place. If the tube becomes obstructed or otherwise malfunctions and cannot decompress the stomach, it potentially increases the risk of an aspiration event secondary to this stenting effect.[22] Prolonged use of NG tubes can irritate the gastric lining, causing gi bleeding.[23] Patients with extensive irrigation with an NG tube can develop electrolyte abnormalities such as hypokalemia.[24] Prolonged pressure on 1 area of the nare can cause nasal pressure ulcers or necrosis.[25] The tube should be retaped intermittently to prevent this complication.

Clinical Significance

Whether decompressing the stomach, providing enteral access for nutrition and medications in a patient unable to tolerate them orally, or ruling out an upper GI source of bleeding in the setting of massive hematochezia, nasogastric tubes are part of the standard of care for many routine health issues. Physicians should readily place nasogastric tubes if indicated and should be able to manage them effectively. Given the potential for major complications, particularly if medications or tube feeds are given intrapulmonary, with inappropriate nasogastric tube placement, the entire healthcare team must know the indications, contraindications, possible complications, and appropriate work-up to confirm placement.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As mentioned above, while having at least 1 assistant nearby when placing a nasogastric tube is helpful, an experienced healthcare provider can generally place 1 alone without much difficulty. Interprofessional care comes into play when maintaining nasogastric tubes. Physicians should check that the nasogastric tube is functioning and not clogged or malfunctioning when they round. Clinicians should also routinely inspect their patients' nasogastric tubes to ensure they are functioning and have a high index of suspicion for potential aspiration events. Frequent examinations by all healthcare providers to ensure the tube is securely in place and properly positioned can also reduce injuries associated with nasogastric tubes.[26]

Media

References

Ten Broek RPG, Krielen P, Di Saverio S, Coccolini F, Biffl WL, Ansaloni L, Velmahos GC, Sartelli M, Fraga GP, Kelly MD, Moore FA, Peitzman AB, Leppaniemi A, Moore EE, Jeekel J, Kluger Y, Sugrue M, Balogh ZJ, Bendinelli C, Civil I, Coimbra R, De Moya M, Ferrada P, Inaba K, Ivatury R, Latifi R, Kashuk JL, Kirkpatrick AW, Maier R, Rizoli S, Sakakushev B, Scalea T, Søreide K, Weber D, Wani I, Abu-Zidan FM, De'Angelis N, Piscioneri F, Galante JM, Catena F, van Goor H. Bologna guidelines for diagnosis and management of adhesive small bowel obstruction (ASBO): 2017 update of the evidence-based guidelines from the world society of emergency surgery ASBO working group. World journal of emergency surgery : WJES. 2018:13():24. doi: 10.1186/s13017-018-0185-2. Epub 2018 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 29946347]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBlumenstein I, Shastri YM, Stein J. Gastroenteric tube feeding: techniques, problems and solutions. World journal of gastroenterology. 2014 Jul 14:20(26):8505-24. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i26.8505. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25024606]

Phillips DE, Sherman IW, Asgarali S, Williams RS. How far to pass a nasogastric tube? Particular reference to the distance from the anterior nares to the upper oesophagus. Journal of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh. 1994 Oct:39(5):295-6 [PubMed PMID: 7861338]

Hanson RL. Predictive criteria for length of nasogastric tube insertion for tube feeding. JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 1979 May-Jun:3(3):160-3 [PubMed PMID: 113579]

Fan PEM, Tan SB, Farah GI, Cheok PG, Chock WT, Sutha W, Xu D, Chua W, Kwan XL, Li CL, Teo WQ, Ang SY. Adequacy of different measurement methods in determining nasogastric tube insertion lengths: An observational study. International journal of nursing studies. 2019 Apr:92():73-78. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.01.003. Epub 2019 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 30743198]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNelson R, Edwards S, Tse B. Prophylactic nasogastric decompression after abdominal surgery. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2007 Jul 18:2007(3):CD004929 [PubMed PMID: 17636780]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKamboj AK, Hoversten P, Leggett CL. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Etiologies and Management. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2019 Apr:94(4):697-703. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2019.01.022. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30947833]

Kessel B,Olsha O,Younis A,Daskal Y,Granovsky E,Alfici R, Evaluation of nasogastric tubes to enable differentiation between upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding in unselected patients with melena. European journal of emergency medicine : official journal of the European Society for Emergency Medicine. 2016 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 25747792]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHuang ES, Karsan S, Kanwal F, Singh I, Makhani M, Spiegel BM. Impact of nasogastric lavage on outcomes in acute GI bleeding. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2011 Nov:74(5):971-80. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.045. Epub 2011 Jul 7 [PubMed PMID: 21737077]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHanna AS, Grindle CR, Patel AA, Rosen MR, Evans JJ. Inadvertent insertion of nasogastric tube into the brain stem and spinal cord after endoscopic skull base surgery. American journal of otolaryngology. 2012 Jan-Feb:33(1):178-80. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.04.001. Epub 2011 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 21715048]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKelly G, Lee P. Nasendoscopically-assisted placement of a nasogastric feeding tube. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 1999 Sep:113(9):839-40 [PubMed PMID: 10664689]

West HH. Topical anesthesia for nasogastric tube placement. Annals of emergency medicine. 1982 Nov:11(11):645 [PubMed PMID: 6982638]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUri O, Yosefov L, Haim A, Behrbalk E, Halpern P. Lidocaine gel as an anesthetic protocol for nasogastric tube insertion in the ED. The American journal of emergency medicine. 2011 May:29(4):386-90. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.10.011. Epub 2010 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 20825806]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCullen L, Taylor D, Taylor S, Chu K. Nebulized lidocaine decreases the discomfort of nasogastric tube insertion: a randomized, double-blind trial. Annals of emergency medicine. 2004 Aug:44(2):131-7 [PubMed PMID: 15278085]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMandal M,Karmakar A,Basu SR, Nasogastric tube insertion in anaesthetised, intubated adult patients: A comparison between three techniques. Indian journal of anaesthesia. 2018 Aug [PubMed PMID: 30166656]

Burns SM, Martin M, Robbins V, Friday T, Coffindaffer M, Burns SC, Burns JE. Comparison of nasogastric tube securing methods and tube types in medical intensive care patients. American journal of critical care : an official publication, American Association of Critical-Care Nurses. 1995 May:4(3):198-203 [PubMed PMID: 7787913]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBoeykens K, Steeman E, Duysburgh I. Reliability of pH measurement and the auscultatory method to confirm the position of a nasogastric tube. International journal of nursing studies. 2014 Nov:51(11):1427-33. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2014.03.004. Epub 2014 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 24731474]

Metheny NA, Krieger MM, Healey F, Meert KL. A review of guidelines to distinguish between gastric and pulmonary placement of nasogastric tubes. Heart & lung : the journal of critical care. 2019 May-Jun:48(3):226-235. doi: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2019.01.003. Epub 2019 Jan 18 [PubMed PMID: 30665700]

Palta S, Nasogastric tube knotting in open heart surgery. Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 1999 Aug [PubMed PMID: 10456824]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGenú PR, de Oliveira DM, Vasconcellos RJ, Nogueira RV, Vasconcelos BC. Inadvertent intracranial placement of a nasogastric tube in a patient with severe craniofacial trauma: a case report. Journal of oral and maxillofacial surgery : official journal of the American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. 2004 Nov:62(11):1435-8 [PubMed PMID: 15510370]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWang PC, Tseng GY, Yang HB, Chou KC, Chen CH. Inadvertent tracheobronchial placement of feeding tube in a mechanically ventilated patient. Journal of the Chinese Medical Association : JCMA. 2008 Jul:71(7):365-7. doi: 10.1016/S1726-4901(08)70141-2. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18653401]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGomes GF, Pisani JC, Macedo ED, Campos AC. The nasogastric feeding tube as a risk factor for aspiration and aspiration pneumonia. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 2003 May:6(3):327-33 [PubMed PMID: 12690267]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMetheny NA,Meert KL,Clouse RE, Complications related to feeding tube placement. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2007 Mar [PubMed PMID: 17268247]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBryant LR, Mobin-Uddin K, Dillon ML, Griffen WO Jr. Comparison of ice water with iced saline solution for gastric lavage in gastroduodenal hemorrhage. American journal of surgery. 1972 Nov:124(5):570-2 [PubMed PMID: 4538731]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLai PB, Pang PC, Chan SK, Lau WY. Necrosis of the nasal ala after improper taping of a nasogastric tube. International journal of clinical practice. 2001 Mar:55(2):145 [PubMed PMID: 11321856]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchroeder J, Sitzer V. Nursing Care Guidelines for Reducing Hospital-Acquired Nasogastric Tube-Related Pressure Injuries. Critical care nurse. 2019 Dec 1:39(6):54-63. doi: 10.4037/ccn2019872. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31961939]