Introduction

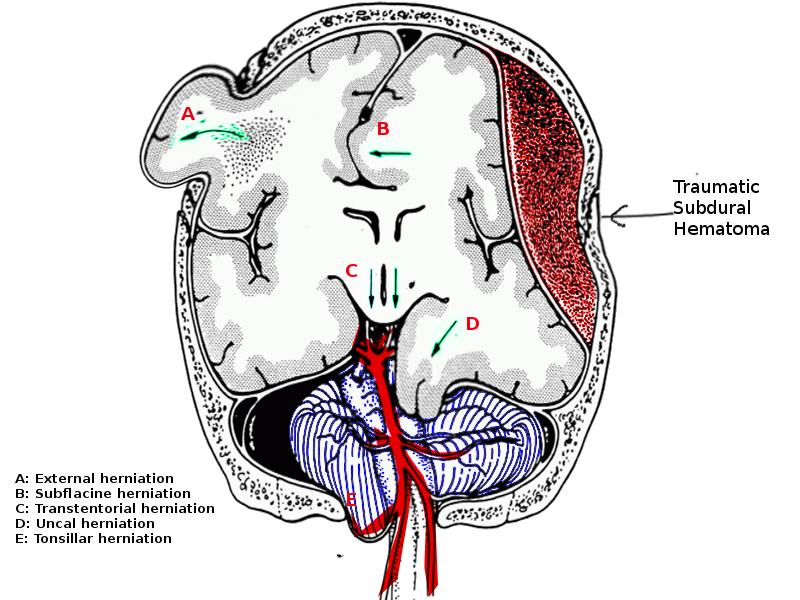

Brain herniation is the movement of brain parenchyma from one cranial compartment to another.[1] The key cranial compartments include left and right supratentorial compartments and the posterior fossa, which is infratentorial. The tentorium cerebelli is a rigid fold of dura that divides the cranial contents into a supratentorial and infratentorial region. The infratentorial region contains the cerebellar and brainstem, while the supratentorial compartment contains the cerebral hemispheres. This is further divided into right and left by the falx cerebri, which is also a fold of dura running within the longitudinal fissure between the two hemispheres. The tentorium cerebelli contains an oval-shaped opening called the tentorial notch or incisor. The midbrain passes through this opening and is continuous with the diencephalon.[2][3] A transtentorial herniation is any parenchymal herniation through the tentorial notch; of which there are three kinds:

- Uncal herniation

- Central herniation

- Upward herniation

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Raised intracranial pressure (ICP) within a compartment can be caused by the following:[3][4]

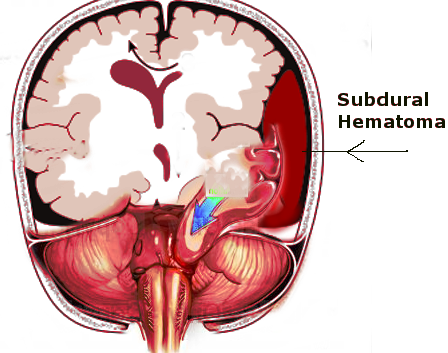

- Hematoma: intracerebral, subarachnoid[5], subdural, extradural, intraventricular, contusion

- Hydrocephalus

- Tumor

- Abscess

- Malignant ischemia such as malignant middle cerebral artery (MCA) syndrome

- Swelling: diffuse axonal injury (DAI)

- Pneumocephalus (traumatic or postoperative)

- cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) over drainage

- Metabolic: hepatic encephalopathy

- Tumefactive multiple sclerosis[6]

Epidemiology

The incidence of transtentorial herniation is not documented, due to it being a physiological response to various underlying pathologies. The most common cause is traumatic brain injury (TBI).[7] A 2019 review estimates the worldwide incidence of TBI to be 69 million per year, with nearly 8% being classed as severe (Glasgow Coma Scale score - GCS - 8 or less).[8] In the United States, the annual incidence of TBI requiring medical attention is approximately 30 million.

Pathophysiology

The tentorium cerebelli is very rigid due to its multiple tethering points. Anteriorly the petrous ridge and posterior clinoid processes secure the sheet-like tentorium. Laterally it forms the transverse sinus and attaches to the inner table of the occipital bone. The tentorium contains an oval-shaped opening through which the midbrain passes and is continuous with the diencephalon.[2]

- The Monro - Kellie doctrine dictates that the cranial vault contains a fixed volume of brain parenchyma, CSF, and blood.[9][10] Once the skull sutures have fused at around 18 months of age, the only remaining inlet or outlet to the cranial vault is through the foramen magnum at the base of the posterior fossa.[3] If there is an increase in the volume of one of the components, then the others must compensate to maintain the equilibrium. For example, if the brain parenchyma swells due to edema or infarct, the volume of CSF within that compartment will reduce, followed by the volume of blood. Another important scenario is the addition of another 'mass', such as a tumor, abscess, or hematoma. These tend to distort brain parenchyma, compress vascular structures, and squeeze CSF out of the compartment. The ability of a given closed compartment to compensate for increases in volumes by decreasing CSF or blood is known as compliance. Once a mass lesion has reached a size where there is little CSF remaining within the compartment, then any further increase in size can produce large increases in compartmental pressures. This is considered a loss of compliance. At this critical stage, any further volume increase can result in herniation of brain tissue out of the high-pressure compartment into another neighboring lower pressure compartment.[3]

There are three particular ways by which herniation can occur through the tentorial notch:

- Uncal herniation

- Central herniation

- Upward herniation

Uncal Herniation

Uncal herniation, as the name suggests, involves the uncal portion of the temporal lobe. The uncus is present in the medial aspect of the temporal lobe. MacEwen first described uncal herniation in the 1880s by freezing and dissecting heads of patients who had died of temporal lobe abscesses.[3] He noted that the medial surface of the temporal uncus was displaced medially and downwards, compressing the oculomotor nerve, which originates from the midbrain. This caused the dilatation of the ipsilateral pupil. The oculomotor nerve leaves the midbrain anteriorly and runs along the underneath surface of the tentorial notch. As the uncus herniates downwards over the notch, it compresses the nerve against the skull base.[3]

Due to the proximity of the uncus to the diencephalon and midbrain, loss of consciousness is a key component of uncal herniation. The distortion of the ascending arousal system that originates in the upper pons and midbrain and ascends through the diencephalon to stimulate the cerebral hemispheres causes changes in arousal. Loss of arousal is a key component of uncal herniation, and therefore pupillary dilatation with preserved consciousness should alert the examiner to search for a different cause.[3]

Hemiparesis is also encountered in these cases and can occur via a few mechanisms. Firstly, a hemispheric lesion can interrupt the corticospinal tracts within that hemisphere, causing contralateral hemiplegia. Secondly, direct compression onto the ipsilateral cerebral peduncle within the midbrain can cause contralateral hemiparesis, again due to the involvement of the corticospinal tract. Lastly, in 1928 Kernohan noted that a supratentorial tumor could cause a lateral shift of the midbrain resulting in compression of the contralateral cerebral peduncle on the edge of the tentorial notch. Due to the decussation of the corticospinal tracts below this level, this 'notching' resulted in ipsilateral hemiparesis. This is an example of a false lateralizing sign as a lesion in the right hemisphere can cause weakness on the right side of the body due to compression of the left cerebral peduncle on the tentorium. Therefore, it is important to acknowledge that hemiparesis cannot be reliable in the localization, and the whole clinical picture should be taken into perspective for an accurate diagnosis of the side of the lesion.[3]

With any supratentorial mass causing tentorial herniation, the posterior cerebral arteries (PCA) can be compressed against the tentorium. The basilar artery ends in two posterior cerebral arteries (PCAs) that travel around the midbrain and along the undersurface of the occipital lobes.[11] The downward pressure of the occipital lobes compresses the PCA against the tentorium. This can cause distal ischemia of the occipital lobes and lead to cortical blindness. This is usually not noted at the time of insult due to the associated loss of consciousness; however, later in the course of the patient's recovery as they awake from the coma, a visual disturbance may be noted.[12] Unilateral ischemia causes hemianopia, whereas bilateral compression results in a cortical blindness syndrome that may include anosognosia.[13]

Central Herniation

Whereas in uncal herniation, the pressure shift causes medial and downward herniation of the uncus, which inevitably compresses the ascending arousal system of the midbrain and diencephalon, central herniation is due to direct pressure on the diencephalon and midbrain itself. Small perforating end arteries are easily stretched and compressed, leading to ischemia and, ultimately, loss of arousal supply the diencephalon. Pupils, due to bilateral compression of the diencephalon, become small but remain reactive. Central herniation can also compress the pituitary stalk, causing a lack of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and diabetes insipidus.[3] Vascular compromise results in ischemia and necrosis of the midbrain. This can lead to distinctive slit-like hemorrhages seen on computed tomogram (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), called Duret hemorrhages.[14]

Upward Herniation

Like supratentorial lesions cause descending herniation through the tentorial notch, though uncommon, posterior fossa lesions can cause upward herniation of the brainstem through the tentorial notch into the supratentorial compartment. Due to the compression of the ascending arousal system, there is a loss of consciousness. There can also be compression of the dorsal midbrain leading to up gaze palsy. If the cerebral aqueduct, which passes through the midbrain, is compressed, then obstructive hydrocephalus will develop.[15] The superior cerebellar artery can also be compressed upwards against the tentorium cerebelli by the cerebellar, causing cerebellar ischemia.[3]

Dorsal Midbrain Compression

Pressure directly upon the dorsal midbrain, also called the tectal plate, can lead to Parinaud syndrome with a distinctive upgaze palsy, pseudo-Argyle Robertson pupil, convergence-retraction nystagmus and, in children, the phenomenon of sun-setting eyes. A pseudo-Argyl Robertson pupil is one that does not react to light due to loss of the reflex arch but still constricts on visual accommodation. Convergence-retraction nystagmus is typified by simultaneous spasmodic contractions of all ocular motility muscles upon the convergence of gaze. This retracts the globes into the orbits. Sun-setting eyes is an exaggerated phenomenon of upgaze palsy, causing the eyes to be in extreme downgaze at rest.[16][3]

Autonomic Supply to the Eye

Sympathetic outflow descends through the brainstem and cervical spine, joining the sympathetic chain at the upper thoracic level. This then ascends in the neck along the carotid artery to innervate the face via the external carotid and the eye via the internal carotid. It is worth noting that in isolated pontine injury, such as a pontine hemorrhage, sympathetic innervation as it descends through the pons is lost. However, parasympathetic innervation from the Edinger-Westphal nucleus within the midbrain continues to supply the eye via the oculomotor nerve. This leads to unopposed parasympathetic innervation and thus pinpoint pupils.[3]

History and Physical

Uncal Herniation

The hallmark of uncal herniation is a fixed and dilated ipsilateral pupil due to compression of the ipsilateral oculomotor nerve. There is usually some ocular motility impairment. However, due to the associated reduction in consciousness, it is difficult to assess on examination. It may be elicited by oculocephalic reflex testing. Distortion of consciousness is such a key component of uncal herniation that pupillary dilatation with normal conscious levels should lead the examiner to focus on other causes of pupillary dysfunction. As described under pathophysiology, contralateral or ipsilateral hemiplegia may occur.[3][17]

Uncal herniation can be broken down into clinical stages, which are early to late oculomotor and midbrain-upper pons stage. The early oculomotor stage results in an ipsilateral enlarged pupil, which may react sluggishly to light. There is a progressive loss of consciousness as the diencephalon and brainstem are distorted. The late oculomotor stage demonstrates complete dilatation of the pupil that is no longer reactive to light. There will usually be a degree of ophthalmoplegia and ptosis, though this is difficult to appreciate on examination as the patient is in a coma. This stage may also demonstrate hemiplegia, which, as discussed above, may be contralateral or ipsilateral. Breathing is typically normal, although the patient may develop a Cheyne-Stokes pattern of respiration.[3][17]

The final stage, midbrain-upper pons, shows midbrain damage and dysfunction; thus, both pupils become fixed at mid-position due to loss of both sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation. Abnormal posturing may occur including decorticate rigidity, as the red nucleus is involved, and decerebrate rigidity as the compression evolves. Once the brainstem stage is established, uncal herniation becomes indistinguishable from central herniation.[3][17]

Central Herniation

Central herniation can be broken down into diencephalic, midbrain-upper pons, lower pons-upper medullary, and medullary stages. The earliest signs of central herniation are due to the diencephalic stage, where dysfunction of the ascending arousal system causes progressive drowsiness, although initially, this may present as behavioral changes, difficulty in concentrating, or confusion. Initially, as the patient becomes drowsier, they will likely stop obeying commands, but may still localize to pain. Pupils tend to be small with minimal reaction to light. However, the ciliospinal reflex should still be present, where the pupils dilate to painful stimuli.[18] Initially, the patient may begin to sigh or yawn. The early stages of central herniation have no focal neurological signs to alert the examiner to a structural lesion. There may be a general increase in tone, known as paratonia. It is difficult to differentiate a structural cause from a metabolic encephalopathy clinically, which is why early intracranial imaging is warranted.[3]

As the pathology advances to the late diencephalic stage, the patient demonstrates a deepening of coma and a loss of motor localization to pain. The grasp reflex becomes prominent as it is a midbrain reflex. Caution must be taken to avoid mistaking a grasp reflex for obeying commands if the patient is asked to squeeze the examiner's hand. As the midbrain becomes involved, higher brain centers' inhibition of the red nucleus is lost, and the rubrospinal tract is disinhibited. This can lead to decorticate posturing.[3] Pupils become irregular, then fixed at the mid position, and there may be a complete loss of oculocephalic eye movements. Eventually, decorticate posturing advances to decerebrate posturing as the rubrospinal tract becomes dysfunctional. As the compression progresses and the pons is involved, breathing may become irregular, and eye movements are lost during caloric testing. Usually, the tone is reduced, and tendon reflexes are difficult to elicit.

The final stage results in medullary involvement, also known as the terminal stage. Breathing slows and may become gasping. There is a surge in adrenaline as the body tries to survive, and the pupils become temporarily dilated. Cushing reflex may be present with high blood pressure and reflexive bradycardia. As the autonomic function is lost, blood pressure may drop, and eventually, cardiac output will cease.

Dorsal Midbrain Compression

The direct pressure on the dorsal midbrain can develop a clinical syndrome known as Parinaud syndrome. It results from compression of the tectal plate, where the superior and inferior colliculi are situated. A lesion in the pineal region, or upward herniation of the brainstem, can cause compression of the tectal plate. The characteristics include slightly enlarged, unreactive pupils and vertical gaze palsy. In severe cases, the eyes may be forced into a downward gaze, sometimes known as' sun-setting eyes.' The patient may develop convergence-retraction nystagmus where all eye muscles contract simultaneously, pulling the eyes back into the orbit. If the cerebral aqueduct, which passes through the midbrain, is compressed, then obstructive hydrocephalus may develop with the associated symptoms of reduced consciousness.[3]

Evaluation

Typically, the GCS is used universally for patients with head injury or any patient with reduced levels of consciousness. This has been criticized, particularly as the GCS scale is not ordinal or linear. For example, losing two points in speech may represent a focal disorder of speech and not a disorder of consciousness. It is well established that the motor component is more sensitive and specific as grading of severity in head injury than the overall GCS.[19]

Radiological imaging such as CT head is mandatory for patients presenting with reduced consciousness unless there is a known medical or metabolic cause, such as hypoglycemia. Patients with unequal pupils and reduced consciousness are very likely to have a surgically amenable lesion and therefore require urgent imaging.[20] On axial imaging, midline shift, and obliteration of the ipsilateral ventricle should alert you to a possible herniation syndrome. On coronal imaging, the uncus can be seen displaced medially and encroaching over the tentorium. In central herniation, there is the obliteration of the basal cisterns and may also be associated with microhemorrhages within the brainstem indicative of Duret hemorrhages, although these are better appreciated on MRI.[3][20]

In the case of PCA occlusion, there may be established ischemic changes in the distribution of the PCAs. With upward herniation, the ischemic changes are more likely to be in the distribution of the superior cerebellar arteries (SCAs) within the cerebellum. With compression of the aqueduct, there may also be hydrocephalus of the lateral and third ventricles. This is particularly common in posterior fossa lesions causing upward herniation and dorsal midbrain compression closing off the aqueduct.[3]

- An intracranial pressure (ICP) monitoring system may be warranted, usually in the form of an ICP bolt. With a herniation syndrome, this will show raised pressures, typically over 20 mmHg, with poor compliance. Poor compliance is represented by P2 being higher than P1 and P3 on the ICP waveform. On an ICP waveform, the P2 represents the ’tidal wave’ of the brain and thus the compliance. P1 is the ‘percussion wave’ or arterial kick during systole. P3 is the venous wave or ‘dicrotic notch.’ In normal physiology, P1 should be higher than P2 that is higher than P3. When compliance is reduced, P2 is the higher wave. This indicates an intracranial system that is unable to compensate for the increased volume, and therefore, the pressure will be rising.[3][21][22][21]

A contentious issue within neurocritical care is that numerous studies have shown control of ICP is key to a good outcome in traumatic brain injury.[23][24][25] However, patients who underwent invasive ICP monitoring had longer lengths of stay in critical care, had more interventions, and ultimately had poorer outcomes than those who were not monitored.[26] A South African study showed that care focused on ICP monitoring had no better outcomes than that reliant on clinical assessment and radiological studies.[27] The evidence suggests that managing patients with neuroprotective measures intended to lower ICP (described below), without actually measuring ICP, gives the best outcome.

An important patient presentation to be mindful of is the head-injured patient who may ’talk and die.’ This is a patient who initially does not exhibit signs of significant brain injury but later after the ‘lucid interval’ deteriorates neurologically into a coma. This is typically seen in extradural hematoma, where the rapid expansion of the hematoma causes a coma.[28]

Treatment / Management

Medical Management

Control of ICP is a mainstay of treatment with severe neurological insult.[28][24] ICP guided therapy includes, but is not exclusive to sedation, oxygenation, control of PaCO2, fluid balance with mean arterial pressure (MAP) targets, normothermia, treatment of sepsis, maintaining adequate hemoglobin level, and nutrition. In regards to neurotrauma and ’neuroprotective measures, there are a number of therapies that have been shown to improve outcomes with varying degrees of evidence.

Level 2 evidence for:

- Avoidance of hypotension (SBP <90 mmHg), as this doubles mortality.[29]

- Prophylactic anti-epileptics reduce early seizures but do not reduce late post-traumatic seizure rates. Late is defined as after one week of the injury.[30][31] (A1)

Level 3 evidence for:

- Secure the airway if GCS 8 or less.[32]

- Avoidance of hypoxia (Saturations <90%), which, if combined with hypotension, triples mortality.[33]

- Target PaCO2 of 5 kPa. Prophylactic hyperventilation has been shown to be detrimental to outcomes; however, it may be used as a temporizing measure in patients with deteriorating neurology. This may be if the patient is being transported to the CT scanner or theatre for intervention.[32][34][35]

- The neuromuscular blockade should be avoided routinely; however, it may be used when sedation alone is inadequate in reducing a monitored intracranial pressure (ICP). Routine use of sedation and paralysis increases the incidence of pneumonia and causes longer ICU stays.[36]

- Mannitol or hypertonic saline are useful agents when there are clinical signs of transtentorial herniation, such as pupillary dilatation.[32][37] It can also be used to assess for salvageability when brainstem reflexes have been lost. Prophylactic use of mannitol is not recommended due to its effects on intravascular volume depletion.[34] Typical doses are 0.5 to 1 g/kg of mannitol as a bolus. In practice, this is 200 to 300 ml of 20%. For hypertonic saline, 3 ml/kg of 3% or 1 to 2 ml/kg of 5% can be used. An advantage of hypertonic saline is that one can monitor its effects by measuring the serum sodium level and, therefore, titrate the infusion if running it continuously. (A1)

Surgery

Patients with traumatic head injuries often have other associated injuries. Over half of the patients with a GCS of 8 or less will have injuries to other organ systems, and 5% will have spinal fractures. 25% of these patients will have an intracranial lesion that may be amenable to surgical evacuation, a so-called ’surgical lesion.’[38](A1)

Surgical options include CSF diversion via ventricular drainage. Hematoma evacuation is the mainstay of treatment for extradural and subdural hematomas. Although, intracerebral hematomas can be managed this way as well; a decompressive craniectomy can also be utilized to allow space for the brain to expand without resulting in herniation syndrome.[17] However, good evidence demonstrates that decompressive craniectomy results in increased survival but not improved functional outcomes.[39]

In regards to timing, Mendelow et al. showed that extradural hematoma should be evacuated within two hours of neurological deterioration to improve mortality and functional outcome.[40] Seelig et al. showed that acute subdural hematoma should be evacuated within 4 hours of injury to improve mortality and functional outcome.[41](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

Other causes of a dilated pupil include a posterior communicating artery aneurysm compressing the oculomotor nerve. Also, medical causes of neuropathy of the third cranial nerve, such as diabetes, can cause pupillary dysfunction. However, these disorders typically have preserved consciousness.[3] There are multiple causes of reduced consciousness and coma, including metabolic and infective encephalopathy. These, however, will not typically cause a focal pupillary dilatation. Although widespread cortical dysfunction or diencephalic dysfunction can cause pupillary abnormalities, they tend to be bilateral. Seizures can also cause pupillary abnormalities, albeit transiently.[3]

Prognosis

A transtentorial herniation is a vital clinical diagnosis due to possible reversibility both with temporizing medical therapies and definitive surgical treatments. Prior to brainstem involvement, both uncal and central herniation can be fully reversible, particularly with etiologies, such as extradural and subdural hematoma. Surgical evacuation of an extra-axial lesion, or emergent tumor debulking, is a time-critical intervention, and thus, early diagnosis and instigation of temporizing therapies as described above are vital.

Once signs of the midbrain and lower brainstem involvement have developed, it becomes increasingly unlikely that the neurological status is reversible, likely due to irreversible ischemia. Once the midbrain stage of herniation is complete full recovery is rare, with less than 5% making a good recovery.[3] Once herniation causes respiratory compromise, there is no chance of a meaningful recovery, and thus, mechanical ventilation is usually not appropriate. It is important at this point to have discussions with the family, and involve the organ donation team.[3]

A series of 153 patients demonstrated that patients in a coma with fixed pupils and abnormal motor responses had a good recovery in only 9% of cases. 60% died, and 10% being classed as severely disabled at delayed follow-up.[42] As with most neurological insults, young age is a better prognostic factor.

Complications

Focal lesions with herniation are considered secondary brain injuries. A significant confounding issue with traumatic brain injuries is the underlying primary brain injury, which occurs at the time of insult. This is not reversible and typically has a worse outcome. As discussed above, varying degrees of visual injury can occur with head trauma, particularly cortical blindness from PCA compression. 5% of head injury patients develop some degree of visual system injury.[43] With central herniation, in particular, there can be pituitary stalk damage with resultant pituitary dysfunction, although this is rare, it can occur with the base of skull fractures.[44]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Given TBI is the most common cause of transtentorial herniation, public health measures to reduce traumatic events such as road traffic collisions are mandatory.[8]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Brain herniation syndromes are a medical emergency and require urgent assessment and intervention from a wide variety of clinical teams. These teams include emergency medicine, anesthetics, intensive care, trauma, orthopedics, and neurosurgery. Close monitoring of neurological status is required throughout the time course of their admission including neurological observations by nursing staff. (Level 2, 3 evidence)

If the patient survives the initial phase, then it is likely neurorehabilitation teams will be required. This is usually a multidisciplinary team approach and will include: physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech and language therapists, dieticians, and psychologists. Though survival is the primary goal, a good functional recovery indicated by a return to activities of daily living is considered equally as valuable.

Media

References

Munakomi S, M Das J. Brain Herniation. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194403]

Adler DE, Milhorat TH. The tentorial notch: anatomical variation, morphometric analysis, and classification in 100 human autopsy cases. Journal of neurosurgery. 2002 Jun:96(6):1103-12 [PubMed PMID: 12066913]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePlum F, Posner JB. The diagnosis of stupor and coma. Contemporary neurology series. 1972:10():1-286 [PubMed PMID: 4664014]

Stevens RD, Shoykhet M, Cadena R. Emergency Neurological Life Support: Intracranial Hypertension and Herniation. Neurocritical care. 2015 Dec:23 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S76-82. doi: 10.1007/s12028-015-0168-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26438459]

Shafique S, Rayi A. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Subarachnoid Space. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 32491453]

Vakharia K, Kamal H, Atwal GS, Budny JL. Transtentorial herniation from tumefactive multiple sclerosis mimicking primary brain tumor. Surgical neurology international. 2018:9():208. doi: 10.4103/sni.sni_131_18. Epub 2018 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 30488006]

Georges A, M Das J. Traumatic Brain Injury. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083790]

Dewan MC, Rattani A, Gupta S, Baticulon RE, Hung YC, Punchak M, Agrawal A, Adeleye AO, Shrime MG, Rubiano AM, Rosenfeld JV, Park KB. Estimating the global incidence of traumatic brain injury. Journal of neurosurgery. 2018 Apr 27:130(4):1080-1097. doi: 10.3171/2017.10.JNS17352. Epub 2018 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 29701556]

Mokri B. The Monro-Kellie hypothesis: applications in CSF volume depletion. Neurology. 2001 Jun 26:56(12):1746-8 [PubMed PMID: 11425944]

Wilson MH. Monro-Kellie 2.0: The dynamic vascular and venous pathophysiological components of intracranial pressure. Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. 2016 Aug:36(8):1338-50. doi: 10.1177/0271678X16648711. Epub 2016 May 12 [PubMed PMID: 27174995]

Javed K, Reddy V, M Das J. Neuroanatomy, Posterior Cerebral Arteries. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30860709]

Sato M, Tanaka S, Kohama A, Fujii C. Occipital lobe infarction caused by tentorial herniation. Neurosurgery. 1986 Mar:18(3):300-5 [PubMed PMID: 3703188]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKeane JR. Blindness following tentorial herniation. Annals of neurology. 1980 Aug:8(2):186-90 [PubMed PMID: 7425572]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParizel PM, Makkat S, Jorens PG, Ozsarlak O, Cras P, Van Goethem JW, van den Hauwe L, Verlooy J, De Schepper AM. Brainstem hemorrhage in descending transtentorial herniation (Duret hemorrhage). Intensive care medicine. 2002 Jan:28(1):85-8 [PubMed PMID: 11819006]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCuneo RA, Caronna JJ, Pitts L, Townsend J, Winestock DP. Upward transtentorial herniation: seven cases and a literature review. Archives of neurology. 1979 Oct:36(10):618-23 [PubMed PMID: 485890]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOuvrier R. Henri Parinaud (1844-1905). Journal of neurology. 2011 Aug:258(8):1571-2. doi: 10.1007/s00415-011-5919-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21327853]

Cadena R, Shoykhet M, Ratcliff JJ. Emergency Neurological Life Support: Intracranial Hypertension and Herniation. Neurocritical care. 2017 Sep:27(Suppl 1):82-88. doi: 10.1007/s12028-017-0454-z. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28913634]

Reeves AG, Posner JB. The ciliospinal response in man. Neurology. 1969 Dec:19(12):1145-52 [PubMed PMID: 5389693]

Price DJ. Is diagnostic severity grading for head injuries possible? Acta neurochirurgica. Supplementum. 1986:36():67-9 [PubMed PMID: 3467566]

Laine FJ, Shedden AI, Dunn MM, Ghatak NR. Acquired intracranial herniations: MR imaging findings. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 1995 Oct:165(4):967-73 [PubMed PMID: 7677003]

Raboel PH, Bartek J Jr, Andresen M, Bellander BM, Romner B. Intracranial Pressure Monitoring: Invasive versus Non-Invasive Methods-A Review. Critical care research and practice. 2012:2012():950393. doi: 10.1155/2012/950393. Epub 2012 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 22720148]

Munakomi S, M Das J. Intracranial Pressure Monitoring. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31194438]

Miller JD, Becker DP, Ward JD, Sullivan HG, Adams WE, Rosner MJ. Significance of intracranial hypertension in severe head injury. Journal of neurosurgery. 1977 Oct:47(4):503-16 [PubMed PMID: 903804]

Miller JD, Butterworth JF, Gudeman SK, Faulkner JE, Choi SC, Selhorst JB, Harbison JW, Lutz HA, Young HF, Becker DP. Further experience in the management of severe head injury. Journal of neurosurgery. 1981 Mar:54(3):289-99 [PubMed PMID: 7463128]

Wilberger JE Jr, Harris M, Diamond DL. Acute subdural hematoma: morbidity, mortality, and operative timing. Journal of neurosurgery. 1991 Feb:74(2):212-8 [PubMed PMID: 1988590]

Stocchetti N, Penny KI, Dearden M, Braakman R, Cohadon F, Iannotti F, Lapierre F, Karimi A, Maas A Jr, Murray GD, Ohman J, Persson L, Servadei F, Teasdale GM, Trojanowski T, Unterberg A, European Brain Injury Consortium. Intensive care management of head-injured patients in Europe: a survey from the European brain injury consortium. Intensive care medicine. 2001 Feb:27(2):400-6 [PubMed PMID: 11396285]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChesnut RM, Temkin N, Carney N, Dikmen S, Rondina C, Videtta W, Petroni G, Lujan S, Pridgeon J, Barber J, Machamer J, Chaddock K, Celix JM, Cherner M, Hendrix T, Global Neurotrauma Research Group. A trial of intracranial-pressure monitoring in traumatic brain injury. The New England journal of medicine. 2012 Dec 27:367(26):2471-81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1207363. Epub 2012 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 23234472]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceReilly PL, Graham DI, Adams JH, Jennett B. Patients with head injury who talk and die. Lancet (London, England). 1975 Aug 30:2(7931):375-7 [PubMed PMID: 51187]

. The Brain Trauma Foundation. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons. The Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Resuscitation of blood pressure and oxygenation. Journal of neurotrauma. 2000 Jun-Jul:17(6-7):471-8 [PubMed PMID: 10937889]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChang BS, Lowenstein DH, Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Practice parameter: antiepileptic drug prophylaxis in severe traumatic brain injury: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2003 Jan 14:60(1):10-6 [PubMed PMID: 12525711]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence. The Brain Trauma Foundation. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons. The Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Role of antiseizure prophylaxis following head injury. Journal of neurotrauma. 2000 Jun-Jul:17(6-7):549-53 [PubMed PMID: 10937900]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence. The Brain Trauma Foundation. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons. The Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Initial management. Journal of neurotrauma. 2000 Jun-Jul:17(6-7):463-9 [PubMed PMID: 10937888]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChesnut RM, Marshall LF, Klauber MR, Blunt BA, Baldwin N, Eisenberg HM, Jane JA, Marmarou A, Foulkes MA. The role of secondary brain injury in determining outcome from severe head injury. The Journal of trauma. 1993 Feb:34(2):216-22 [PubMed PMID: 8459458]

Bullock R, Chesnut RM, Clifton G, Ghajar J, Marion DW, Narayan RK, Newell DW, Pitts LH, Rosner MJ, Wilberger JW. Guidelines for the management of severe head injury. Brain Trauma Foundation. European journal of emergency medicine : official journal of the European Society for Emergency Medicine. 1996 Jun:3(2):109-27 [PubMed PMID: 9028756]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence. The Brain Trauma Foundation. The American Association of Neurological Surgeons. The Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care. Hyperventilation. Journal of neurotrauma. 2000 Jun-Jul:17(6-7):513-20 [PubMed PMID: 10937894]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHsiang JK, Chesnut RM, Crisp CB, Klauber MR, Blunt BA, Marshall LF. Early, routine paralysis for intracranial pressure control in severe head injury: is it necessary? Critical care medicine. 1994 Sep:22(9):1471-6 [PubMed PMID: 8062572]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGu J, Huang H, Huang Y, Sun H, Xu H. Hypertonic saline or mannitol for treating elevated intracranial pressure in traumatic brain injury: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurosurgical review. 2019 Jun:42(2):499-509. doi: 10.1007/s10143-018-0991-8. Epub 2018 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 29905883]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSaul TG, Ducker TB. Effect of intracranial pressure monitoring and aggressive treatment on mortality in severe head injury. Journal of neurosurgery. 1982 Apr:56(4):498-503 [PubMed PMID: 6801218]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence. Trial of decompressive craniectomy for traumatic intracranial hypertension. Journal of the Intensive Care Society. 2017 Aug:18(3):236-238. doi: 10.1177/1751143716685246. Epub 2017 Jun 29 [PubMed PMID: 29118837]

Mendelow AD, Karmi MZ, Paul KS, Fuller GA, Gillingham FJ. Extradural haematoma: effect of delayed treatment. British medical journal. 1979 May 12:1(6173):1240-2 [PubMed PMID: 455011]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSeelig JM, Becker DP, Miller JD, Greenberg RP, Ward JD, Choi SC. Traumatic acute subdural hematoma: major mortality reduction in comatose patients treated within four hours. The New England journal of medicine. 1981 Jun 18:304(25):1511-8 [PubMed PMID: 7231489]

Andrews BT, Pitts LH. Functional recovery after traumatic transtentorial herniation. Neurosurgery. 1991 Aug:29(2):227-31 [PubMed PMID: 1886660]

Kline LB, Morawetz RB, Swaid SN. Indirect injury of the optic nerve. Neurosurgery. 1984 Jun:14(6):756-64 [PubMed PMID: 6462414]

Vance ML. Hypopituitarism. The New England journal of medicine. 1994 Jun 9:330(23):1651-62 [PubMed PMID: 8043090]