Introduction

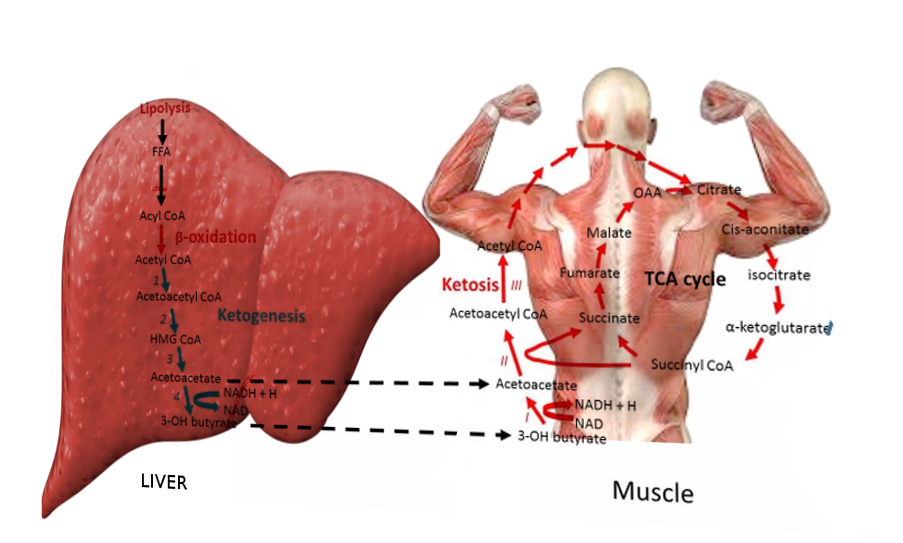

Ketoacidosis is a metabolic state associated with pathologically high serum and urine concentrations of ketone bodies, namely acetone, acetoacetate, and beta-hydroxybutyrate. During catabolic states, fatty acids are metabolized to ketone bodies, which can be readily utilized for fuel by individual cells in the body. Of the three major ketone bodies, acetoacetic acid is the only true ketoacid chemically, while beta-hydroxybutyric acid is a hydroxy acid, and acetone is a true ketone. Figure 1 shows the schematic of ketogenesis where the fatty acids generated after lipolysis in the adipose tissues enter the hepatocytes via the bloodstream and undergo beta-oxidation to form the various ketone bodies. This biochemical cascade is stimulated by the combination of low insulin levels and high glucagon levels (i.e., a low insulin/glucagon ratio). Low insulin levels, most often secondary to absolute or relative hypoglycemia as with fasting, activate hormone-sensitive lipase, which is responsible for the breakdown of triglycerides to free fatty acid and glycerol.

The clinically relevant ketoacidoses to be discussed include diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), alcoholic ketoacidosis (AKA), and starvation ketoacidosis. DKA is a potentially life-threatening complication of uncontrolled diabetes mellitus if not recognized and treated early. It typically occurs in the setting of hyperglycemia with relative or absolute insulin deficiency. The paucity of insulin causes unopposed lipolysis and oxidation of free fatty acids, resulting in ketone body production and subsequent increased anion gap metabolic acidosis. Alcoholic ketoacidosis occurs in patients with chronic alcohol abuse, liver disease, and acute alcohol ingestion. Starvation ketoacidosis occurs after the body is deprived of glucose as the primary source of energy for a prolonged time, and fatty acids replace glucose as the major metabolic fuel.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

DKA can occur in patients with diabetes mellitus, most frequently associated with relative insulin deficiency. This may be caused by precipitating physiologic stress or, in some cases, maybe the initial clinical presentation in patients with previously undiagnosed diabetes. Some of the more common risk factors that can precipitate the development of extreme hyperglycemia and subsequent ketoacidosis are infection, non-adherence to insulin therapy, acute major illnesses like myocardial infarction, sepsis, pancreatitis, stress, trauma, and the use of certain medications, such as glucocorticoids or atypical antipsychotic agents which have the potential to affect carbohydrate metabolism.[1]

AKA occurs in patients with chronic alcohol abuse. Patients can have a long-standing history of alcohol use and may also present following binges. Acetic acid is a product of the metabolism of alcohol and also a substrate for ketogenesis. The conversion to acetyl CoA and subsequent entry into various pathways or cycles, one of which is the ketogenesis pathway is determined by the availability of insulin in proportion to the counter-regulatory hormones, which are discussed in more detail below.

Under normal conditions, cells rely on free blood glucose as the primary energy source, which is regulated with insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin. As the name implies, starvation ketoacidosis is a bodily response to prolonged fasting hypoglycemia, which decreases insulin secretion, shunting the biochemistry towards lipolysis and the oxidation of the by-product fatty acids to ensure a fuel source for the body.

Epidemiology

DKA occurs more frequently with type 1 diabetes, although 10% to 30% of cases occur in patients with type 2 diabetes,[2] in situations of extreme physiologic stress or acute illness. According to the morbidity and mortality review of the CDC, diabetes itself is one of the most common chronic conditions in the world and affects an estimated 30 million people in the United States. Age-adjusted DKA hospitalization rates were on the downward trend in the 2000s but have steadily been increasing from thereafter till the mid-2010s at an average annual rate of 6.3%,[3] while there has been a decline in in-hospital case-fatality rates during this period.

For AKA, the prevalence correlates with the incidence of alcohol abuse without racial or gender differences in incidence. It can occur at any age and mainly in chronic alcoholics but rarely in binge drinkers.[4]

For starvation ketosis, mild ketosis generally develops after a 12- to 14-hour fast. If there is no food source, as in the case of extreme socio-economic deprivation or eating disorders, this will cause the body’s biochemistry to transform from ketosis to ketoacidosis progressively, as described below. It can be seen in cachexia due to underlying malignancy, patients with postoperative or post-radiation dysphagia, and prolonged poor oral intake.

Pathophysiology

Glucose is the primary carbon-based substrate in blood necessary for the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which is the energy currency of cells after glucose is metabolized during glycolysis, Kreb’s cycle and the electron transport chain. Ketone bodies are fat-derived fuels used by tissues at the time of limited glucose availability. Hepatic generation of ketone bodies is usually stimulated by the combination of low insulin levels and high counter-regulatory hormone levels, including glucagon.

Low insulin levels are seen inherently in as either an absolute or relative deficiency in type I diabetes or a relative deficiency with insulin resistance in type 2 diabetes. In alcoholic or starvation conditions, low insulin levels are secondary to absolute or relative hypoglycemia. This unfavorable ratio of insulin to glucagon activates hormone-sensitive lipase, which breaks down triglycerides in peripheral fat stores, releasing long-chain fatty acids and glycerol. The fatty acids undergo beta-oxidation in the hepatic mitochondria and generate acetyl-CoA. With the generation of large quantities of acetyl-CoA in the more severe forms of each of these conditions, the oxidative capacity of the Krebs cycle gets saturated, and there is a spillover entry of acetyl-CoA into the ketogenic pathway and subsequent generation of ketone bodies. An increased anion gap metabolic acidosis occurs when these ketone bodies are present as they are unmeasured anions.

Alcoholic ketoacidosis[5] occurs in patients with chronic alcohol abuse and liver disease and usually develops following abrupt withdrawal of alcohol or an episode of acute intoxication. It is not uncommon for the ingested ethanol to have already been metabolized, leading to low or normal serum levels when checked. In normal alcohol metabolism, the ingested ethanol is oxidized to acetaldehyde and then to acetic acid with the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase, during which process the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) is reduced to NADH. The acetic acid can be shunted towards ketogenesis in favorable insulin/glucagon concentrations, which is seen in hypoglycemia. In addition to this, the increased NADH further suppresses gluconeogenesis and reduces free glucose, perpetuating ketogenesis.[6] After abrupt withdrawal, rising catecholamine levels as a bodily response cause lipolysis and ketosis. The high ratio of NADH to NAD+ also favors the reduction of acetoacetate to beta-hydroxybutyrate.

In extremes of starvation, after the exhaustion of the free glucose and after that, the body’s glycogen reserves, fatty acids become the primary fuel source. This usually happens after 2 or 3 days of fasting. After several days of fasting, protein catabolism starts, and muscles are broken down, releasing amino acids and lactate into the bloodstream, which can be converted into glucose by the liver. This biochemical process is responsible for the wasting and cachexia seen during starvation.

History and Physical

Patients with DKA may have a myriad of symptoms on presentation, usually within several hours of the inciting event. Symptoms of hyperglycemia are common, including polyuria, polydipsia, and sometimes more severe presentations include unintentional weight loss, vomiting, weakness, and mentation changes. Dehydration and metabolic abnormalities worsen with progressive uncontrolled osmolar stress, which can lead to lethargy, obtundation, and may even cause respiratory failure, coma, and death. Abdominal pain is also a common complaint in DKA. Patients with AKA usually present with abdominal pain and vomiting after abruptly stopping alcohol.

On physical exam, most of the patients with ketoacidoses present with features of hypovolemia from gastrointestinal or renal fluid and electrolyte losses. In severe cases, patients may be hypotensive and in frank shock. They may have a rapid and deep respiratory effort as a compensatory mechanism, known as Kussmaul breathing. They may have a distinct fruity odor to their breath, mainly because of acetone production. There may be neurological deficits in DKA, but less often in AKA. AKA patients may have signs of withdrawal like hypertension and tachycardia. There are signs of muscle wasting in patients with starvation ketoacidosis like poor muscle mass, minimal body fat, obvious bony prominences, temporal wasting, tooth decay, sparse, thin, dry hair and low blood pressure, pulse, and temperature.

Evaluation

The initial laboratory evaluation of a patient with suspected DKA includes blood levels of glucose, ketones, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, electrolytes, calculated anion gap, arterial blood gases, osmolality, complete blood count with differential, blood cultures and urine studies including ketones, urinalysis, urine culture, chest radiograph, and an electrocardiogram. Hyperglycemia is the typical finding at presentation with DKA, but patients can present with a range of plasma glucose values. Although ketone levels are generally elevated in DKA, a negative measurement initially does not exclude the diagnosis because ketone laboratory measurements often use the nitroprusside reaction, which only estimates acetoacetate and acetone levels that may not be elevated initially as beta-hydroxybutyrate is the major ketone that is elevated. The anion-gap is elevated, as mentioned above, because ketones are unmeasured anions. Leukocytosis may indicate an infectious pathology as the trigger and cultures are sent from blood, urine, or other samples as clinically indicated. Serum sodium is usually relatively low because of shifts of solvent (water) from the intracellular to extracellular spaces because of the osmotic pull of hyperglycemia. Hence, normal or elevated serum sodium is indicative of severe volume depletion. Serum potassium levels may be elevated due to shifts from the intracellular compartment for exchange with acids in the absence of insulin and normal or low potassium, indicating an overall depleted body store and subsequent need for correction before initiation of insulin therapy.

In AKA, transaminitis, and hyperbilirubinemia due to concurrent alcoholic hepatitis may also be present. The alcohol level itself need not be elevated as the more severe ketoacidosis is seen once the level falls, and the counter-regulatory response begins and shunts the metabolism towards lipolysis. Hypokalemia and increased anion-gap are usually seen with similar mechanisms to those seen in DKA.

Hypomagnesemia and hypophosphatemia are common problems seen in the laboratory evaluation due to decreased dietary intake and increased losses. As mentioned above, the direct measurement of serum beta-hydroxybutyrate is more sensitive and specific than the measurement of urine ketones. Starvation ketoacidoses patients may again have multiple electrolyte abnormalities due to chronic malnutrition, along with vitamin deficiencies. The pH may not be as low as in DKA or AKA, and the glucose levels may be relatively normal.

Treatment / Management

After the initial stabilization of circulation, airway, and breathing as a priority, specific treatment of DKA requires correction of hyperglycemia with intravenous insulin, frequent monitoring, and replacement of electrolytes, mainly potassium, correction of hypovolemia with intravenous fluids, and correction of acidosis. Given the potential severity and the need for frequent monitoring for intravenous insulin therapy and possible arrhythmias, patients may be admitted to the intensive care unit. Blood glucose levels and electrolytes should be monitored on an hourly basis during the initial phase of management.

Aggressive volume resuscitation with isotonic saline infusion is recommended in the initial management of DKA. Volume expansion not only corrects the hemodynamic instability but also improves insulin sensitivity and reduces counter-regulatory hormone levels. After starting with isotonic saline, the subsequent options can be decided on the serum sodium levels that are corrected for the level of hyperglycemia. Normal or high serum sodium levels warrant replacement with hypotonic saline, and low sodium levels warrant continuation of the isotonic saline. This fluid has to be supplemented with dextrose once the level reaches around 200 to 250 mg/dl. Along with fluids, an intravenous infusion of regular insulin has to be initiated to maintain the blood glucose level between 150 to 200 mg/dl and until the high anion-gap acidosis is resolved in DKA. Like mentioned above, potassium levels are usually high because of the transcellular shifts due to the acidosis and the lack of insulin. When the potassium levels are low, this means that the total body potassium is low, and hence, insulin therapy should be postponed till at least the level of serum potassium is greater than 3.3 mEq/L. Otherwise, a further drop in levels would put the patient at risk for cardiac arrhythmias. In the 3.3 to 5 mEq/L; range, supplementation should be added in the maintenance fluids to target a steady 4.0 to 5.0 mEq/L range, and if higher than that, insulin and intravenous fluids alone can be started with just the frequent monitoring of the serum potassium level. The treatment of the acidosis itself is more controversial. Treatment with sodium bicarbonate therapy is controversial. It has been studied and found to provide no added benefit when the arterial blood pH is greater than 6.9 and may be associated with more harm.[7] A 2011 systematic review found that bicarbonate administration worsened ketonemia. Several studies have found higher potassium requirements in patients receiving bicarbonate. Studies in children have observed a possible association between bicarbonate therapy and cerebral edema.[8](A1)

AKA typically responds to treatment with intravenous saline and intravenous glucose, with rapid clearance of the associated ketones due to a reduction in counter-regulatory hormones and the induction of endogenous insulin. Like in DKA, this is the first step in management because of the need for correction the hypovolemia/shock. Thiamine replacement is important in alcohol-related presentations, including intoxication, withdrawal, and ketoacidosis, and should be initially done parenterally and after that maintained orally. Electrolyte replacement is critical. Potassium losses that occur through gastrointestinal (GI) or renal losses should be monitored and replaced closely as glucose in the replacement fluid induces endogenous insulin, which in turn drives the extracellular potassium inside the cells. Also of paramount importance is monitoring and replacing the magnesium and phosphate levels, which are usually low in both chronic alcoholism and prolonged dietary deprivation as in starvation.

The treatment of starvation ketoacidosis is similar to AKA. Patients need to be monitored for refeeding syndrome, which is associated with electrolyte abnormalities seen when aggressive feeding is started in an individual starved for a prolonged time. The resultant insulin secreted causes significant transcellular shifts, and hence similar to AKA, monitoring and replacing potassium, phosphate, and magnesium is very important.

Differential Diagnosis

Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic state (HHS) occurs in the setting of insulin resistance and is more typical of type 2 diabetes. There is sufficient insulin in patients with HHS to suppress lipolysis and production of ketone bodies, but inadequate amounts to prevent the hyperglycemia, dehydration, and hyperosmolality, characteristic of HHS. An illness or event that leads to dehydration will often precipitate the hyperglycemia associated with HHS. The development of HHS is less acute than DKA and may take days to weeks to develop. HHS typically presents with more extreme hyperglycemia and mental status changes compared with DKA. HHS typically presents with normal or small amounts of urine or serum ketones. Plasma glucose values in HHS are typically greater than in DKA and can exceed 1200 mg/dL (66.6 mmol/L). The serum osmolality is elevated greater than 320 mOsm/kg H2O. The serum bicarbonate level is greater than 18 mEq/L (18 mmol/L), and the pH remains greater than 7.3.

Lactic acidosis is an alternative cause of an increased anion gap metabolic acidosis. Lactic acidosis is found with tissue hypoperfusion, hematological malignancies, and various medications.

Rhabdomyolysis is a diagnostic consideration in a patient with a history of alcohol use disorder and an anion gap metabolic acidosis, but this condition is frequently associated with hyperkalemia, hyperphosphatemia, hypocalcemia, and a urinalysis positive for blood with no erythrocytes visible on urine microscopy.

Acute abdominal surgical emergencies, such as acute pancreatitis, should be considered differentials when abdominal pain is the main presentation.

Pearls and Other Issues

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American College of Endocrinology have reviewed reported cases of DKA in patients taking SGLT2 inhibitors.[9] This association is weak; however, if DKA develops in patients taking SGLT2 inhibitors, stop the drug immediately, and proceed with traditional DKA treatment protocols. When DKA is found in patients using SGLT2 inhibitors, it is often “euglycemic” DKA, defined as glucose less than 250. Therefore, rather than relying on the presence of hyperglycemia, close attention to signs and symptoms of DKA is needed.

In May 2015, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a warning [B] that treatment with sodium-glucose transporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors, which include canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and empagliflozin, may increase the risk of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) in patients with diabetes mellitus. The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database identified 20 cases of DKA in patients treated with SGLT2 inhibitors from March 2013 to June 2014.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Diabetes, once diagnosed, is mostly managed with changes in diet, lifestyle, and medication adherence. The goal is to prevent high glucose levels, which helps prevent diabetic complications. To prevent the complications of diabetes like ketoacidosis, the condition is best managed by an interprofessional team that includes the diabetic nurse educator, dietician, nurse practitioner, pharmacist, primary care provider, and an endocrinologist; all these clinicians should educate the patient on glucose control at every opportunity.

Empowering the patient regarding management is hence of the utmost importance. Diabetes self-management education (DSME) and diabetes self-management support (DSMS) are recommended at the time of diagnosis of prediabetes or diabetes and throughout the lifetime of the patient. DSMS is an individualized plan that provides opportunities for educational and motivational support for diabetes self-management. DSME and DSMS jointly provide an opportunity for collaboration between the patient and health care providers to assess educational needs and abilities, develop personal treatment goals, learn self-management skills, and provide ongoing psychosocial and clinical support.

The diabetic nurse should follow all outpatients to ensure medication compliance, followup with clinicians, and adopting a positive lifestyle. Further, the nurse should teach the patient how to monitor home blood glucose and the importance of careful monitoring of blood sugars during infection, stress, or trauma. The physical therapist should be involved in educating the patient on exercise and the importance of maintaining healthy body weight.

The social worker should be involved to ensure that the patient has the support services and financial assistance to undergo treatment. The members of the interprofessional team should communicate to ensure that the patient is receiving the optimal standard of care.

Improved outcomes and reduced costs have been associated with DSME and DSMS.[10][11]

Media

References

Newcomer JW. Second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and metabolic effects: a comprehensive literature review. CNS drugs. 2005:19 Suppl 1():1-93 [PubMed PMID: 15998156]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNyenwe EA, Kitabchi AE. The evolution of diabetic ketoacidosis: An update of its etiology, pathogenesis and management. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2016 Apr:65(4):507-21. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.12.007. Epub 2015 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 26975543]

Benoit SR, Zhang Y, Geiss LS, Gregg EW, Albright A. Trends in Diabetic Ketoacidosis Hospitalizations and In-Hospital Mortality - United States, 2000-2014. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2018 Mar 30:67(12):362-365. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6712a3. Epub 2018 Mar 30 [PubMed PMID: 29596400]

Howard RD, Bokhari SRA. Alcoholic Ketoacidosis. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 28613672]

Allison MG, McCurdy MT. Alcoholic metabolic emergencies. Emergency medicine clinics of North America. 2014 May:32(2):293-301. doi: 10.1016/j.emc.2013.12.002. Epub 2014 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 24766933]

Krebs HA, Freedland RA, Hems R, Stubbs M. Inhibition of hepatic gluconeogenesis by ethanol. The Biochemical journal. 1969 Mar:112(1):117-24 [PubMed PMID: 5774487]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChua HR, Schneider A, Bellomo R. Bicarbonate in diabetic ketoacidosis - a systematic review. Annals of intensive care. 2011 Jul 6:1(1):23. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-1-23. Epub 2011 Jul 6 [PubMed PMID: 21906367]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWilson JF. In clinic. Diabetic ketoacidosis. Annals of internal medicine. 2010 Jan 5:152(1):ITC1-1, ITC1-2, ITC1-3,ITC1-4, ITC1-5, ITC1-6, ITC1-7, ITC1-8, ITC1-9, ITC1-10, ITC1-11, ITC1-12, ITC1-13, ITC1-14, ITC1-15, table of contents; quiz ITC1-16. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-1-201001050-01001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20048266]

Handelsman Y, Henry RR, Bloomgarden ZT, Dagogo-Jack S, DeFronzo RA, Einhorn D, Ferrannini E, Fonseca VA, Garber AJ, Grunberger G, LeRoith D, Umpierrez GE, Weir MR. AMERICAN ASSOCIATION OF CLINICAL ENDOCRINOLOGISTS AND AMERICAN COLLEGE OF ENDOCRINOLOGY POSITION STATEMENT ON THE ASSOCIATION OF SGLT-2 INHIBITORS AND DIABETIC KETOACIDOSIS. Endocrine practice : official journal of the American College of Endocrinology and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists. 2016 Jun:22(6):753-62. doi: 10.4158/EP161292.PS. Epub 2016 Jun 1 [PubMed PMID: 27082665]

Seckold R, Fisher E, de Bock M, King BR, Smart CE. The ups and downs of low-carbohydrate diets in the management of Type 1 diabetes: a review of clinical outcomes. Diabetic medicine : a journal of the British Diabetic Association. 2019 Mar:36(3):326-334. doi: 10.1111/dme.13845. Epub 2018 Nov 19 [PubMed PMID: 30362180]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGeorge JT, Mishra AK, Iyadurai R. Correlation between the outcomes and severity of diabetic ketoacidosis: A retrospective pilot study. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2018 Jul-Aug:7(4):787-790. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_116_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30234054]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence