Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are a cluster of nano-sized vesicles of different sizes, cargo, and surface markers that are secreted into the extracellular environment through a variety of mechanisms. They carry various components of the cytoplasm and cell membrane that are selectively loaded into these vesicles. They are secreted by all forms of living cells and play essential roles in different physiological functions and pathological processes. They also have been utilized as Diagnostic markers and therapeutic tools in several conditions.

Three types of EVs are biologically distinguishable from one another via the distinct processes through which they are released by the cell. However, the experimental classification of these vesicles is less clear as there is no consensus on what criteria to use for their differentiation. The first type is the microvesicles (MVs), or the ectosomes. These vesicles arise by direct budding through the cell membrane to the outside of the cell.[1] The second type is the exosomes, which are first formed by budding into the endosomes to create what is called the multivesicular bodies (MVBs). These MVBs either fuse with lysosomes, resulting in content digestion, or fuse with the cell membrane, which results in the content released as exosomes.[2] The third type arises from the cells during the process of apoptosis, hence its name apoptotic bodies (APBs). APBs emerge either by separation of the membrane blebs or from apoptopodia that arise during the process of apoptosis. There are two types of apoptopodia: non-beaded and beaded. The distinction in the course and the roles of these different routes is still under investigation.[3]

Source

EVs are secreted by all ranges of organisms, from prokaryotes to unicellular eukaryotes - like protozoa, yeasts, and fungi - to mammals. They can be isolated from all bodily fluids, including blood, plasma, serum, saliva, urine, sweat, cerebrospinal fluid, breast milk, and semen. In humans, these EVs have been reported to be secreted by nearly all types of cells in our physique, including but not limited to immune cells, endothelial cells, red blood cells, erythrocytes, liver cells, and epithelial cells.

Characterization

After their isolation, it is necessary to confirm that the required population of EVs has been obtained. Scientists utilize several techniques to do this confirmation. First is the electron microscope. The regular scanning electron microscope shows EVs as irregular shaped membrane-enclosed vesicles. Alternatively, cryo-electron microscopy can be utilized. Despite being time-consuming and expensive, it gives more accurate information about the shape and size of the isolated vesicles. The second method of characterization is nano-track analysis, which provides a general idea about the concentration and size distribution of the isolated vesicles. The third method is a western blot, which is used to recognize protein markers associated with the membrane of the EVs. Despite some distinction of specific proteins on the surfaces of different EVs, there is still no consensus on which proteins can be used reliably as markers for the different types.[4] Recently, flow cytometry procedures have been developed to characterize different types of EVs based on their surface markers.[5]

Structure

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure

The vesicles are surrounded by phospholipid bilayer membrane similar to the one that surrounds the cells.[6] However, lipidemic and proteomic studies showed that the membrane of the vesicles has its natural lipid and protein profile. One of the unique features of this profile, for example, is the high level of the lysoglycerophospholipid, which is absent in the other cellular membranes.[7] They also reach in cholesterol, ceramides, and sphingomyelin. Regarding the protein content of the vesicle membrane, it shows heterogeneity not only between EVs isolated from different cells but even between EVs isolated from the same type of cells under various conditions. However, some proteins are common in different EVs like tetraspanins and integrins families, which are used as markers for characterization of the isolated EVs.[8]

Size

Although the different types of vesicles have distinct size ranges, there is still overlap, making classification based solely on size not possible.[9] Exosomes range in size from 50 to 150 nm, while microvesicles range from 100 to 1000 nm.[10] The range of the APBs is much broader, from 50 to 5000 nm in diameter.[11]

Cargo

EVs may contain any content found in their origin cell’s cytoplasm; this includes proteins, mRNA, miRNA, long noncoding RNAs (lncRNA), circular RNAs (circRNA), metabolites, and lipids.[12][13]. Some research showed an association between DNA and EVs.[14][15] Furthermore, some APBs contain intact cell organelles like mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, and ribosomes.[11]

Function

The EVs exert their functions through different mechanisms. They can transfer their cargo or membrane constituents from one cell to another, thus transferring functions between cells. In doing so, they perform several roles based on the type of donor and recipient cells.[16] Also, they carry molecules on their surface, which act as ligands that would stimulate surface receptors in other cells activating intracellular signaling.[17] Alternatively, these surface molecules can directly perform functions in the extracellular milieu. For example, exosomes may carry on their surface matrix remodeling enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases, heparanases, and hyaluronidases, which play roles in several physiological and pathological conditions.[18]

Another mechanism of EVs function is what we can call "the decoy" function in which surface proteins on the EVs membrane capture external molecules or pathogens to neutralize their effects. Whatever is the mechanism of action, the final role of EVs, either physiological or pathological, depends on their cell of origin and the conditions through which they have been stimulated. These factors determine the final cargo of the EVs and the lipid and protein content of their membranes, which, by turn, decides their ultimate destination and actions.

EVs play essential roles in several physiological processes, like embryonic growth, pregnancy, blood hemostasis, and body metabolism. With regards to coagulation functions, EVs were first identified as "platelet dust," which were described as factors in the plasma that enhance the coagulation process. These platelet dust were recognized later as the "platelet-derived EVs." Molecules exposed on the surface of these EVs, such as the tissue factor or phosphatidylserine, work as activators of the coagulation cascade. These types of EVs are available in the blood during injury or endothelial damage, but they are absent in healthy circulating blood. On the other hand, normal circulating EVs carry plasminogen activators, so they induce fibrinolytic activity, preventing thrombus formation. Additionally, exosomes released from platelets under normal conditions inhibit platelet aggregation.[19]

EVs also play essential metabolic functions; this occurs by transferring enzymes and metabolites between cells or by performing extracellular metabolic activities. This reason is why some scientists call them "metabolic nanomachines."[20] Studies showed that EVs secreted by the liver cells contain hundreds of enzymes that belong to the different metabolic pathways. When these EVs were incubated with rat serum, they changed the metabolic profile of the serum, indicating a functional role of these EVs. However, the specific functional roles of these enzymes outside the cells are yet to be identified.[21]

The role of EVs in the Host-pathogen Relationship

EVs plays several roles in the war between the human body and its invaders. They are utilized by both sides, endeavoring to win the war. This process applies to all types of pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, fungi, and parasites. The pathogens, for instance, could use their EVs to evade the immune system through several mechanisms like complement inhibition and antibody degradation. This process is in addition to the direct utilization of the EVs in their pathogenic actions like delivery of virulence factors, disruption of natural barriers, cytotoxicity, and modulation of host cells.[22][23]

Proteomic studies on bacterial EVs suggested that the protein cargo of these EVs have been loaded selectively from the cytoplasm, and not randomly, to perform these functions.[24] Also, bacterial EVs mediates the non-genetic acquisition of antibacterial resistance. One example is the ability of EVs to transfer b-lactamase protein to bacteria that are not genetically expressing it.[25]

On the other hand, EVs play essential roles in the recognition and destruction of the microbes by the immune system. Different components of the innate and the adaptive immune systems communicate EVs among each other to orchestrate their actions aiming at combating the invaders. This process involves EVs from several sources, including both the pathogen and the host immune and non-immune cells. Besides, the immune system utilizes these EVs as direct tools in their war against these attackers. For example, decoy exosomes carry molecules that neutralize bacterial toxins like diphtheria toxins and toxins released by Staphylococcus aureus.[26]

Another example is that MVs released from neutrophils under the effect of specific bacterial stimulation play direct antibacterial actions against the stimulating bacteria.[27][28] Likewise, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) and epithelial cells derived exosomes exert a direct antiviral activity through different mechanisms, including neutralization of the virus through the specific virus receptor loaded on their surface. Recent research illustrated such an effect against HIV by EVs derived from human placental trophoblast or CD4+ T-lymphocytes.[29][30]

EVs isolated from different body fluids carry immune response-related and immune-modulatory molecules. These molecules include proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids. EVs released by different types of immune cells vary in their content and surface markers and perform different roles in the immune system.[31] A prominent example is that EVs from microbes, host dendritic cells, or B lymphocytes have been acknowledged as "miniature antigen-presenting cells surrogates" as they transfer antigens directly to the T-lymphocytes leading to their activation.[32]

Pathophysiology

EVs are involved in the pathogenesis of several diseases, including cancer, Alzheimer disease, hypertension, and diabetes.[33] Regarding cancer, EVs have correlations with the different hallmarks of cancer. As an example, EVs sustain the proliferation signal in cancer cells through the direct transfer of the message to the inside of the cells or through stimulation of surface receptors by ligands integrated into the vesicle membrane.

EVs also carry miRNAs that repress tumor suppression proteins. Additionally, EVs represent a mechanism through which cells can discard tumor suppressor signals, effectively down-regulating them and allowing for cell proliferation. The most studied roles of EVs in cancer include cell migration, invasion, and metastasis.

EVs from the metastatic cancer cells stimulates the migration and invasion of less metastatic cells; this occurs through different mechanisms, including the transfer of proteins or mRNA that enhance the process of invasion and migration. Also, EVs from cancer cells carry molecules, such as matrix metalloproteinase, on their surface that assist in the destruction of extracellular matrices and so aid in the process of cancer cell migration. Another significant role of EVs is through the preparation of the metastatic niche to receive migrating cancer cells.[34]

Clinical Significance

EVs have a wide range of clinical applications that includes both diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Additionally, their use as vaccines or vaccine adjuvants has shown promising results in basic and preclinical research, and few of these applications have entered clinical studies. For example, EVs offer a promising role as diagnostic markers for thrombotic diseases, cancer, and neurological diseases such as Alzheimer's and multiple sclerosis. EVs isolated from blood or tissue fluid samples from patients with these diseases have shown different cargo and surface markers as compared to those isolated from non-diseased individuals. Recognizing these differences provides necessary tools for early diagnosis and the prognosis of these diseases. An example is the change of profile of lysoglycerophospholipid in the membrane of EVs isolated from the serum of cancer patients.[35]

Both natural and engineered EVs could be useful in the treatment of a variety of diseases. Also, EVs could be utilized as drug or gene delivery vehicles. In fact, EVs isolated from mesenchymal stem cells are an example of a natural EV that harbors therapeutic effects. The regenerative effect of MSCs is a consequence of their paracrine action rather than the direct replacement of the injured tissue, so the administration of conditioned medium or EVs derived from the stem cells has a regenerative effect equivalent to that produced by the stem cells themselves. MSC-derived EVs improved several conditions in experimental animals, including diabetic nephropathy and diabetic retinopathy.[36]

MSC-derived exosomes are now in a clinical trial as a regenerative treatment for COVID19 patients with severe lung injury. These exosomes repair the damage caused by the virus in lung and respiratory epithelial cells. In addition to their regenerative effect, EVs extracted from bone marrow MSCs showed other benefits like reduction of tumor growth when injected in mouse models with hepatocellular carcinoma.[37] The use of the EVs has several advantages over the stem cells as scientists consider injecting EVs as safer than stem cells as stem cells maintain a low probability of oncogenicity or mutagenicity potential. Moreover, EVs can be stored easily for later use and commercial production.

The engineered EVs also carry great potential as a therapy for several diseases; this includes cancer, immune-associated diseases, neurological, metabolic, and infectious diseases. Scientists adopted several strategies to engineer EVs for therapeutic purposes. One approach is to insert proteins on the membrane of the vesicle that has a therapeutic benefit or that target EVs to a specific type of cells like cancer cells. They also modified the content of the EVs to carry a particular protein or nucleic acid that would combat a particular disease. Grafting of the EVs with artificial nanoparticles is another strategy that could improve the kinetics or the targeting of the EVs. Many potential anticancer and antimicrobial therapies have been invented and at different stages of the trials. For example, EVs carrying ACE2, the receptor of the COVID19 virus, showed promising results regarding their use as antiviral medicine.[38]

EVs serve as vaccines in different ways. One example is the direct utilization of microbe-derived EVs as vaccines, which were proven to be effective in protecting against some bacterial diseases. EVs derived from the outer membrane of the gram-negative Neisseria meningitides, also called outer membrane vesicles (OMVs), are currently used as a vaccine against meningitis that is already licensed by several countries all over the world. Another way to use EVs as vaccines is to load microbial surface antigens on EV membranes. This method gives the vaccine higher potency than when using the soluble form of the antigen. Also, the EVs are efficient carriers for DNA and RNA vaccines. They protect the nucleic acid and increase the vaccine potency. Additionally, they are effective adjuvants for different types of vaccines. A unique advantage of the EVs is their potential to carry more than one component of the vaccine, giving a chance for higher potency.[39]

In conclusion, the emerging field of extracellular vesicles allows for a greater understanding of the mechanisms of most biological processes and diseases. Besides, EVs are potential tools for diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of many diseases. The field is still in its beginning, and a lot of effort by physicians and researchers is needed to unlock these possibilities. Involving EVs in the curricula of undergraduate and medical students is necessary to push the process and get the utmost out of these potentials.

Media

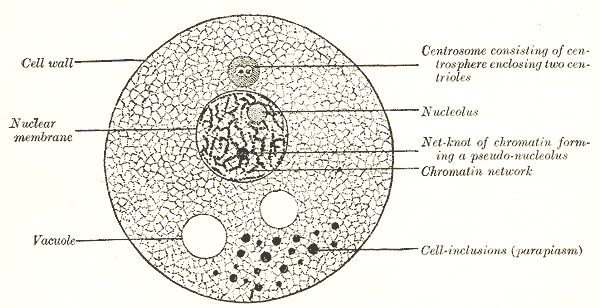

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tricarico C, Clancy J, D'Souza-Schorey C. Biology and biogenesis of shed microvesicles. Small GTPases. 2017 Oct 2:8(4):220-232. doi: 10.1080/21541248.2016.1215283. Epub 2016 Aug 5 [PubMed PMID: 27494381]

Hessvik NP, Llorente A. Current knowledge on exosome biogenesis and release. Cellular and molecular life sciences : CMLS. 2018 Jan:75(2):193-208. doi: 10.1007/s00018-017-2595-9. Epub 2017 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 28733901]

Atkin-Smith GK, Tixeira R, Paone S, Mathivanan S, Collins C, Liem M, Goodall KJ, Ravichandran KS, Hulett MD, Poon IK. A novel mechanism of generating extracellular vesicles during apoptosis via a beads-on-a-string membrane structure. Nature communications. 2015 Jun 15:6():7439. doi: 10.1038/ncomms8439. Epub 2015 Jun 15 [PubMed PMID: 26074490]

Chiang CY, Chen C. Toward characterizing extracellular vesicles at a single-particle level. Journal of biomedical science. 2019 Jan 15:26(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12929-019-0502-4. Epub 2019 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 30646920]

Arkesteijn GJA, Lozano-Andrés E, Libregts SFWM, Wauben MHM. Improved Flow Cytometric Light Scatter Detection of Submicron-Sized Particles by Reduction of Optical Background Signals. Cytometry. Part A : the journal of the International Society for Analytical Cytology. 2020 Jun:97(6):610-619. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.24036. Epub 2020 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 32459071]

Margolis L, Sadovsky Y. The biology of extracellular vesicles: The known unknowns. PLoS biology. 2019 Jul:17(7):e3000363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000363. Epub 2019 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 31318874]

Sun Y, Saito K, Saito Y. Lipid Profile Characterization and Lipoprotein Comparison of Extracellular Vesicles from Human Plasma and Serum. Metabolites. 2019 Nov 1:9(11):. doi: 10.3390/metabo9110259. Epub 2019 Nov 1 [PubMed PMID: 31683897]

Meldolesi J. Exosomes and Ectosomes in Intercellular Communication. Current biology : CB. 2018 Apr 23:28(8):R435-R444. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2018.01.059. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29689228]

Witwer KW, Soekmadji C, Hill AF, Wauben MH, Buzás EI, Di Vizio D, Falcon-Perez JM, Gardiner C, Hochberg F, Kurochkin IV, Lötvall J, Mathivanan S, Nieuwland R, Sahoo S, Tahara H, Torrecilhas AC, Weaver AM, Yin H, Zheng L, Gho YS, Quesenberry P, Théry C. Updating the MISEV minimal requirements for extracellular vesicle studies: building bridges to reproducibility. Journal of extracellular vesicles. 2017:6(1):1396823. doi: 10.1080/20013078.2017.1396823. Epub 2017 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 29184626]

Borges FT, Reis LA, Schor N. Extracellular vesicles: structure, function, and potential clinical uses in renal diseases. Brazilian journal of medical and biological research = Revista brasileira de pesquisas medicas e biologicas. 2013 Oct:46(10):824-30. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20132964. Epub 2013 Oct 2 [PubMed PMID: 24141609]

Kakarla R, Hur J, Kim YJ, Kim J, Chwae YJ. Apoptotic cell-derived exosomes: messages from dying cells. Experimental & molecular medicine. 2020 Jan:52(1):1-6. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0362-8. Epub 2020 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 31915368]

Shi X, Wang B, Feng X, Xu Y, Lu K, Sun M. circRNAs and Exosomes: A Mysterious Frontier for Human Cancer. Molecular therapy. Nucleic acids. 2020 Mar 6:19():384-392. doi: 10.1016/j.omtn.2019.11.023. Epub 2019 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 31887549]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAbels ER, Breakefield XO. Introduction to Extracellular Vesicles: Biogenesis, RNA Cargo Selection, Content, Release, and Uptake. Cellular and molecular neurobiology. 2016 Apr:36(3):301-12. doi: 10.1007/s10571-016-0366-z. Epub 2016 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 27053351]

Ronquist KG, Ronquist G, Carlsson L, Larsson A. Human prostasomes contain chromosomal DNA. The Prostate. 2009 May 15:69(7):737-43. doi: 10.1002/pros.20921. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19143024]

Waldenström A, Gennebäck N, Hellman U, Ronquist G. Cardiomyocyte microvesicles contain DNA/RNA and convey biological messages to target cells. PloS one. 2012:7(4):e34653. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034653. Epub 2012 Apr 10 [PubMed PMID: 22506041]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMathieu M, Martin-Jaular L, Lavieu G, Théry C. Specificities of secretion and uptake of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles for cell-to-cell communication. Nature cell biology. 2019 Jan:21(1):9-17. doi: 10.1038/s41556-018-0250-9. Epub 2019 Jan 2 [PubMed PMID: 30602770]

Maia J, Caja S, Strano Moraes MC, Couto N, Costa-Silva B. Exosome-Based Cell-Cell Communication in the Tumor Microenvironment. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology. 2018:6():18. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00018. Epub 2018 Feb 20 [PubMed PMID: 29515996]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNawaz M, Shah N, Zanetti BR, Maugeri M, Silvestre RN, Fatima F, Neder L, Valadi H. Extracellular Vesicles and Matrix Remodeling Enzymes: The Emerging Roles in Extracellular Matrix Remodeling, Progression of Diseases and Tissue Repair. Cells. 2018 Oct 13:7(10):. doi: 10.3390/cells7100167. Epub 2018 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 30322133]

Zarà M, Guidetti GF, Camera M, Canobbio I, Amadio P, Torti M, Tremoli E, Barbieri SS. Biology and Role of Extracellular Vesicles (EVs) in the Pathogenesis of Thrombosis. International journal of molecular sciences. 2019 Jun 11:20(11):. doi: 10.3390/ijms20112840. Epub 2019 Jun 11 [PubMed PMID: 31212641]

Williams C, Palviainen M, Reichardt NC, Siljander PR, Falcón-Pérez JM. Metabolomics Applied to the Study of Extracellular Vesicles. Metabolites. 2019 Nov 12:9(11):. doi: 10.3390/metabo9110276. Epub 2019 Nov 12 [PubMed PMID: 31718094]

Royo F, Moreno L, Mleczko J, Palomo L, Gonzalez E, Cabrera D, Cogolludo A, Vizcaino FP, van-Liempd S, Falcon-Perez JM. Hepatocyte-secreted extracellular vesicles modify blood metabolome and endothelial function by an arginase-dependent mechanism. Scientific reports. 2017 Feb 17:7():42798. doi: 10.1038/srep42798. Epub 2017 Feb 17 [PubMed PMID: 28211494]

Kuipers ME, Hokke CH, Smits HH, Nolte-'t Hoen ENM. Pathogen-Derived Extracellular Vesicle-Associated Molecules That Affect the Host Immune System: An Overview. Frontiers in microbiology. 2018:9():2182. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02182. Epub 2018 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 30258429]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLiu Y, Defourny KAY, Smid EJ, Abee T. Gram-Positive Bacterial Extracellular Vesicles and Their Impact on Health and Disease. Frontiers in microbiology. 2018:9():1502. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01502. Epub 2018 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 30038605]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee J, Kim OY, Gho YS. Proteomic profiling of Gram-negative bacterial outer membrane vesicles: Current perspectives. Proteomics. Clinical applications. 2016 Oct:10(9-10):897-909. doi: 10.1002/prca.201600032. Epub 2016 Sep 22 [PubMed PMID: 27480505]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLee J, Lee EY, Kim SH, Kim DK, Park KS, Kim KP, Kim YK, Roh TY, Gho YS. Staphylococcus aureus extracellular vesicles carry biologically active β-lactamase. Antimicrobial agents and chemotherapy. 2013 Jun:57(6):2589-95. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00522-12. Epub 2013 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 23529736]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKeller MD, Ching KL, Liang FX, Dhabaria A, Tam K, Ueberheide BM, Unutmaz D, Torres VJ, Cadwell K. Decoy exosomes provide protection against bacterial toxins. Nature. 2020 Mar:579(7798):260-264. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2066-6. Epub 2020 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 32132711]

Timár CI, Lorincz AM, Csépányi-Kömi R, Vályi-Nagy A, Nagy G, Buzás EI, Iványi Z, Kittel A, Powell DW, McLeish KR, Ligeti E. Antibacterial effect of microvesicles released from human neutrophilic granulocytes. Blood. 2013 Jan 17:121(3):510-8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-431114. Epub 2012 Nov 8 [PubMed PMID: 23144171]

Lőrincz ÁM, Schütte M, Timár CI, Veres DS, Kittel Á, McLeish KR, Merchant ML, Ligeti E. Functionally and morphologically distinct populations of extracellular vesicles produced by human neutrophilic granulocytes. Journal of leukocyte biology. 2015 Oct:98(4):583-9. doi: 10.1189/jlb.3VMA1014-514R. Epub 2015 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 25986013]

Delorme-Axford E, Donker RB, Mouillet JF, Chu T, Bayer A, Ouyang Y, Wang T, Stolz DB, Sarkar SN, Morelli AE, Sadovsky Y, Coyne CB. Human placental trophoblasts confer viral resistance to recipient cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013 Jul 16:110(29):12048-53. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1304718110. Epub 2013 Jul 1 [PubMed PMID: 23818581]

de Carvalho JV, de Castro RO, da Silva EZ, Silveira PP, da Silva-Januário ME, Arruda E, Jamur MC, Oliver C, Aguiar RS, daSilva LL. Nef neutralizes the ability of exosomes from CD4+ T cells to act as decoys during HIV-1 infection. PloS one. 2014:9(11):e113691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113691. Epub 2014 Nov 25 [PubMed PMID: 25423108]

Meldolesi J. Extracellular vesicles, news about their role in immune cells: physiology, pathology and diseases. Clinical and experimental immunology. 2019 Jun:196(3):318-327. doi: 10.1111/cei.13274. Epub 2019 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 30756386]

Clayton A, Mason MD. Exosomes in tumour immunity. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont.). 2009 May:16(3):46-9 [PubMed PMID: 19526085]

Yamamoto S, Azuma E, Muramatsu M, Hamashima T, Ishii Y, Sasahara M. Significance of Extracellular Vesicles: Pathobiological Roles in Disease. Cell structure and function. 2016 Nov 25:41(2):137-143 [PubMed PMID: 27679938]

Xavier CPR, Caires HR, Barbosa MAG, Bergantim R, Guimarães JE, Vasconcelos MH. The Role of Extracellular Vesicles in the Hallmarks of Cancer and Drug Resistance. Cells. 2020 May 6:9(5):. doi: 10.3390/cells9051141. Epub 2020 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 32384712]

Lea J, Sharma R, Yang F, Zhu H, Ward ES, Schroit AJ. Detection of phosphatidylserine-positive exosomes as a diagnostic marker for ovarian malignancies: a proof of concept study. Oncotarget. 2017 Feb 28:8(9):14395-14407. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14795. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28122335]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceEbrahim N, Ahmed IA, Hussien NI, Dessouky AA, Farid AS, Elshazly AM, Mostafa O, Gazzar WBE, Sorour SM, Seleem Y, Hussein AM, Sabry D. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Derived Exosomes Ameliorated Diabetic Nephropathy by Autophagy Induction through the mTOR Signaling Pathway. Cells. 2018 Nov 22:7(12):. doi: 10.3390/cells7120226. Epub 2018 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 30467302]

Alzahrani FA, El-Magd MA, Abdelfattah-Hassan A, Saleh AA, Saadeldin IM, El-Shetry ES, Badawy AA, Alkarim S. Potential Effect of Exosomes Derived from Cancer Stem Cells and MSCs on Progression of DEN-Induced HCC in Rats. Stem cells international. 2018:2018():8058979. doi: 10.1155/2018/8058979. Epub 2018 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 30224923]

Murphy DE, de Jong OG, Brouwer M, Wood MJ, Lavieu G, Schiffelers RM, Vader P. Extracellular vesicle-based therapeutics: natural versus engineered targeting and trafficking. Experimental & molecular medicine. 2019 Mar 15:51(3):1-12. doi: 10.1038/s12276-019-0223-5. Epub 2019 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 30872574]

György B, Hung ME, Breakefield XO, Leonard JN. Therapeutic applications of extracellular vesicles: clinical promise and open questions. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2015:55():439-464. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pharmtox-010814-124630. Epub 2014 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 25292428]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence