Introduction

The thoracic duct is the largest lymphatic duct in the body,[1] with a typical length of 45 cm and a diameter of 2 to 5 mm. It drains lymph from the whole body except the right hemithorax, the right side of the head and neck, and the right upper limb. Chylothorax is the term used for thoracic duct leak and collection into the pleural space.

The thoracic duct typically starts at the second lumbar vertebra at the cisterna chyli, ending at the junction of the left subclavian and jugular veins. A total of 1.5 to 2 liters of lymph flows through the thoracic duct per day.[2][3] Any leak from this system results in significant morbidity with loss of lymph and secondarily causing respiratory distress.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The etiology of thoracic duct leaks can be traumatic and non-traumatic. However, trauma-related etiologies are more common.

A. Traumatic causes include surgical and non-surgical

- Surgical causes: Iatrogenic injury while performing procedures on the esophagus, aorta, pleura, lung, vagotomy, spine surgery, and others. One of the leading reasons for the damage of the thoracic duct during surgical interventions is its anatomical variation.[1][4] A variation is seen in almost one-third of the population.[5]

- Non-surgical causes: Penetrating or non-penetrating trauma to the neck, thorax, upper abdomen, and occasionally due to straining or forceful vomiting and subclavian vein canalization are among the non-surgical causes.

B. Non-traumatic can be further categorized into malignant and non-malignant etiologies.

- Malignant causes: Lymphomas and non-lymphomatous causes include primary lung cancers, mediastinal tumors, sarcomas, and leukemia.

- Non-malignant causes: It can be due to benign tumors, cirrhosis of the liver, thoracic aortic aneurysm, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, protein-losing enteropathy, tuberous sclerosis, and in developing countries, tuberculosis.[6]

Among the above, surgical and tumors are the most frequent causes of chylothorax.[5]

Epidemiology

Thoracic duct leak most often is observed after esophagectomy in about 3% and up to 6% of pediatric patients undergoing cardiac surgeries. Approximately 3% of the patients with blunt thoracic trauma and 1.3% of penetrating thoracic trauma demonstrate thoracic duct leaks.[7]

Pathophysiology

The thoracic duct is more like a vein histologically with the primary function of transporting chyle from the gastrointestinal tract into a systemic venous system. It carries almost 4 liters of chyle daily, most of which originates in the digestive tract. The flow rate can be up to 100 ml/kg/day, depending on the diet consumed. A combination of intrathoracic and intraabdominal pressures and arterial pulsations helps in maintaining lymph flow in the thoracic duct.

Chyle is rich in chylomicrons, triglycerides, cholesterol, fat-soluble vitamins and also contains albumin in high concentrations (12-14 g/L). Thoracic lymph also contains lymphocytes, which account for 95% of the cell content, and this keeps chyle mostly sterile. Electrolytes and other enzymes levels resemble that of the plasma.[8][9]

Because of its unique contents, a thoracic duct leak can have multiple effects such as mechanical compression on the heart leading to tamponade, volume loss, pleural effusion, and pulmonary atelectasis, all of which can occur in an acute event.[10]

In the chronic phase, with depletion of chyle, depression of immunity is observed due to a fall in cellular and humoral immunity attributed to lymphocyte and immunoglobulin depletion. Also, patients may have severe malnutrition with loss of absorbed fat. Hence complications can occur in up to 50% of patients.[10][11]

History and Physical

Symptom onset depends on the etiology, with traumatic or surgical causes presenting earlier compared to the other etiologies.

Typically, patients present with dyspnea due to pleural effusion. Chronically leaking chyle also results in malnourishment and susceptibility to infections, which is seen in non-traumatic causes (e.g., malignancy). However, in surgical and traumatic causes, the symptom onset may be immediate if the volume is more than 500 ml/day.

Examination reveals decreased breath sounds and also dullness to percussion in areas of lymph collection.

Evaluation

Blood investigations: Complete blood count, serum glucose, total protein, triglycerides, albumin, and LDH are done routinely.

Imaging: A chest radiograph may show pleural effusion. Usually, it is unilateral in up to 78% of patients, and it involves the right hemithorax more commonly.[12]

The varied course of the thoracic duct and its site of leak dictates the side of pleural effusion. Hence, injury to the duct below the 5th thoracic vertebrae results in pleural effusion on the right side, and damage above this level occurs in a left-sided pleural effusion.[13] Diseases can also disrupt multiple tributaries to the thoracic duct that can produce pleural effusion unilaterally or bilaterally.

Suspicion should arise when a pleural effusion is recurrent or persistent, more so when it is milky, turbid, or serosanguinous on aspiration. However, the classically described appearance of milky or opalescent aspirate is not universal and is seen in only up to 50% of patients with a thoracic duct leak.[14]

Pleural fluid analysis: Fluid appearance should be noted. The white cell count typically has a lymphocyte predominance with a nucleated cell count greater than 70%. Also, lymphocytes found would be a polyclonal population of T cells.[13]

Electrolyte and protein content is similar to the plasma. LDH content is usually low, and a high level signifies a malignant etiology. Glucose levels are similar to plasma, and a level less than 60 mg/dL, indicates either an infection or a malignant pleural effusion. Triglyceride levels >110mg/dL and cholesterol <200 mg/dL is typically found in patients suspected to have chylothorax. A triglyceride level >240 mg/dL has a sensitivity and specificity of >95%.[15]

The definitive diagnostic test is the detection of chylomicrons in the fluid by lipoprotein electrophoresis, though not performed routinely due to its high expense and availability. Chylomicrons can also be detected by cytological analysis of the obtained fluid with Sudan III, although this is a sensitive test but not specific. Hence it is usually combined with fluid analysis to increase its accuracy.[4]

After confirming the presence of chylothorax, patients require additional evaluation to find the etiology for the leak, and that includes computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen. Though at times, CT may not provide the site of the leak and also in the presence of thoracic duct anomalies, CT may not yield much information. Lymphangiography is a dye study where a dye (methylene blue) is injected in the subcutis of digits and is carried by the pedal lymphatics into the central system. Also, lipiodol contrast can be injected into the lymphatic vessel, and the probable site of the leak and anatomical variation can be visualized using fluoroscopy.

Lymphoscintigraphy is the injection of a technetium 99-labeled agent into the dorsum of the foot bilaterally. Later, imaging is done with single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT)/CT, which gives a good visualization of the thoracic duct.

Recent studies suggest that near-infra-red fluorescence is nonionizing imaging and an easy-to-use method to detect thoracic duct leaks in open surgery or thoracoscopic interventions. Yet, no application to percutaneous sclerotherapy has been described, and hence it can also be a useful tool for percutaneous sclerotherapy.[16]

Treatment / Management

Management includes addressing the leak and also the etiology of the leak after diagnosis. Thoracic duct leak is classified into low output if the volume is < 1 liter and high volume if > 1 liter.

Low output chylothorax - Drainage of the fluid in symptomatic patients along with dietary control measures and concomitantly treating the underlying cause is the goal of treatment. Octreotide is often used to reduce the number of leaks and to avoid surgery.

High output chylothorax - Most commonly seen post-surgically. Though conservative management is tried initially, many end up needing an intervention such as thoracic duct ligation or embolization.[17](B2)

Ancillary measures include complete bowel rest, initiation of parenteral nutrition, and also octreotide/somatostatin and etilefrine therapy for patients awaiting surgery.[4] The timing of surgery is debated, with some advocating the immediate postoperative day and others suggesting initial conservative management for five days and then surgery in failed cases.[18](B3)

Alternatively, non-surgical treatment, including thoracic duct embolization or disruption, may be utilized in high-risk patients.[10][19][20] Because of the high success rate and very low morbidity and mortality, thoracic duct embolization has become the first line of treatment in recent years for the treatment of chylothorax.[21] Embolization of the thoracic duct is a percutaneous technique that normally includes pedal or intranodal lymphangiography,[22] thoracic duct transabdominal catheterization, and glue embolization.(B2)

An alternative route to approach the thoracic duct is by retrograde transvenous approach or even direct ultrasound-guided puncture in the neck followed by embolization.[23] Thoracic duct embolization is usually performed by the percutaneous transabdominal method, and the supply route is blocked using N-butyl cyanoacrylate that is well mixed with lipiodol.[24] The success rate of thoracic duct embolization is almost 70%.[4] Postoperative complications of this procedure include chronic diarrhea, lower extremity edema, and abdominal ascites.[21](B3)

In post-pneumonectomy patients with chylothorax, the leak is managed without chest tube drainage if there is no evidence of a mediastinal shift. A drain may be a necessity if there is a contralateral mediastinal shift, and further evaluation for thoracic duct ligation or embolization should be carried out. Thoracic fistulas are usually treated by direct suture ligation of the thoracic duct with or without adjuncts, including biologic glues or sclerosing agents.[25] If the chylothorax is detected after three weeks postoperatively, then better results are obtained when the sinus tract dilatation technique is used with cavity visualization and clipping of the leaking channel.[26](B3)

Efficacy of conservative management depends on etiology and volume of pleural fluid drainage, with benign conditions such as infection or sarcoidosis. [27](B3)

Pleurodesis: In patients who are not surgical candidates, pleurodesis is an option and is done by installing substances like talc or chemicals such as bleomycin and tetracycline through a catheter into the chest drainage. In surgical pleurodesis with abrasion, pleurectomy can be done during thoracotomy or thoracoscopically, depending on the fitness of the patient. It is observed that surgical pleurodesis is more effective compared to medical pleurodesis.[12][28](B2)

Thoracic duct ligation and thoracic duct embolization are done through catheterization and embolization or disruption of prominent retroperitoneal lymphatics. After every thoracic duct ligation, it is advisable to confirm by looking at their frozen section tissues.[25](B3)

Shunts: In patients with failed definitive procedures, a pleuroperitoneal or pleurovenous shunt may be performed.[29]

Bypass: Terminal thoracic duct bypass is said to be a novel procedure that improves the condition and also cures patients suffering from thoracic leaks due to central conducting lymphatic anomalies.[30]

Differential Diagnosis

Differential diagnosis includes:

- Milky appearing fluid may be due to cholesterol effusion, empyema, and tube feed or lipid leak.

- Non-milky fluid- Exudative effusion due to bacterial/tubercular or atypical cases of pneumonia. Pancreatitis, radiation therapy, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), hypothyroidism, and lupus pleuritis are other causes of non-milky fluid collection.

Prognosis

A large portion of patients improve with conservative management and hence have a good prognosis. Patients with a malignant etiology or in whom the chyle leak cannot be controlled have a poor prognosis. A mortality rate of almost 50% is seen in these patients when their chylothorax is not treated.[10]

Complications

Complications of chylothorax are due to persistent loss of chyle, which contains considerable amounts of fat and fat-soluble vitamins, proteins, electrolytes, and immune system components such as T-lymphocytes and immunoglobulins resulting in impaired immunity and malnutrition.[31]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

- Care of intercostal drainage tube (ICD) or indwelling catheter and accurate measurement of the chyle output.

- Adequate replenishment of electrolytes, with monitoring of serum lymphocyte counts, albumin, total protein, and weight should be considered.

- Oral or enteral low-fat diet.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients with a low output thoracic duct leak who are managed conservatively should be counseled for strict dietary suggestions and frequent monitoring of blood parameters such as electrolytes, leukocyte count, and proteins. Adequate hygiene of the ICD should be maintained. Infection is a possibility, and in such cases, computed tomography may be indicated.

Pearls and Other Issues

The most common cause for thoracic duct leak is surgical, typically after surgeries on the esophagus, lung, or heart.

Most are low output leaks and can be managed conservatively with a low-fat diet, and in symptomatic patients, thoracocentesis or sometimes a chest tube may be needed.

- Chyle leak should be suspected in the post-surgical period when there is a serosanguinous fluid or milky fluid in the drain.

- A triglyceride level >110 mg/dL in the fluid is indicative of a chyle leak.

- CT scan is useful in diagnosing a chyle leak.

- Lymphangiogrpahy and lymphoscintigraphy have a higher sensitivity in diagnosing a chyle leak.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Thoracic duct leaks can result in significant morbidity and mortality if not recognized, more so in the intraoperative period where most of the injuries occur. An interprofessional team approach is beneficial for patients with thoracic duct leaks. Close cooperation between the critical care team is required in the immediate postoperative period to manage electrolyte imbalance and diminished immunity. A cardiothoracic surgeon is needed to assess the need for drainage of the chyle leak. Teamwork involving interventional radiologists in an early period may be needed for a probable intervention such as thoracic duct embolization or disruption. Nursing involvement in the care of the ICD should start immediately after the procedure.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Lymphatic System. Illustrated anatomy includes the cervical lymph nodes, lymphatics of the mammary gland, cisterna chyli, lumbar lymph nodes, pelvic lymph nodes, lymphatics of the lower limb, thoracic duct, thymus, axillary lymph nodes, spleen, lymphatics of the upper limb, and inguinal lymph nodes.

Contributed by B Parker

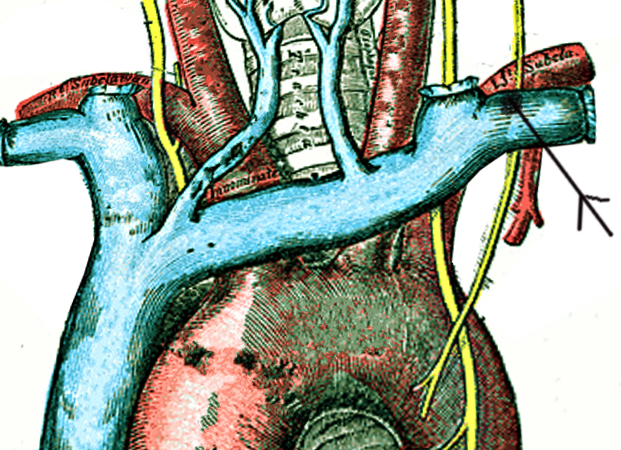

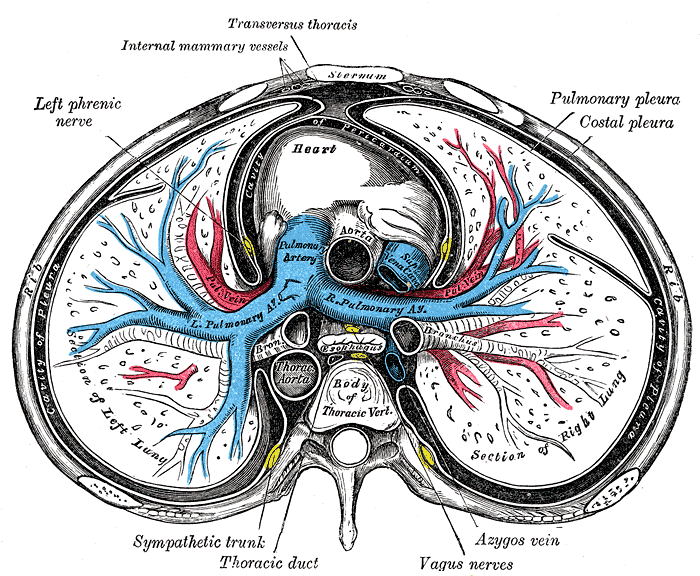

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Sternum Transverse Section. This illustration shows the anatomic relationships between the right and left lungs, heart, pulmonary pleura, costal pleura, pleural cavity, ascending and thoracic aorta, pulmonary artery and its right and left branches, superior vena cava, esophagus, main bronchi, azygos vein, vagus nerves, thoracic duct, sympathetic trunk, left phrenic nerve, internal mammary vessel, transversus thoracis muscle, rib, sternum, and thoracic vertebral body.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Derakhshan A, Lubelski D, Steinmetz MP, Corriveau M, Lee S, Pace JR, Smith GA, Gokaslan Z, Bydon M, Arnold PM, Fehlings MG, Riew KD, Mroz TE. Thoracic Duct Injury Following Cervical Spine Surgery: A Multicenter Retrospective Review. Global spine journal. 2017 Apr:7(1 Suppl):115S-119S. doi: 10.1177/2192568216688194. Epub 2017 Apr 1 [PubMed PMID: 28451482]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWeidner WA, Steiner RM. Roentgenographic demonstration of intrapulmonary and pleural lymphatics during lymphangiography. Radiology. 1971 Sep:100(3):533-9 [PubMed PMID: 4327846]

Macfarlane JR, Holman CW. Chylothorax. The American review of respiratory disease. 1972 Feb:105(2):287-91 [PubMed PMID: 5066693]

Atie M, Dunn G, Falk GL. Chlyous leak after radical oesophagectomy: Thoracic duct lymphangiography and embolisation (TDE)-A case report. International journal of surgery case reports. 2016:23():12-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2016.04.002. Epub 2016 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 27082992]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchild HH, Strassburg CP, Welz A, Kalff J. Treatment options in patients with chylothorax. Deutsches Arzteblatt international. 2013 Nov 29:110(48):819-26. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0819. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24333368]

Doerr CH, Allen MS, Nichols FC 3rd, Ryu JH. Etiology of chylothorax in 203 patients. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2005 Jul:80(7):867-70 [PubMed PMID: 16007891]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSoto-Martinez M, Massie J. Chylothorax: diagnosis and management in children. Paediatric respiratory reviews. 2009 Dec:10(4):199-207. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2009.06.008. Epub 2009 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 19879510]

Robinson CL. The management of chylothorax. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1985 Jan:39(1):90-5 [PubMed PMID: 3966842]

Chalret du Rieu M, Baulieux J, Rode A, Mabrut JY. Management of postoperative chylothorax. Journal of visceral surgery. 2011 Oct:148(5):e346-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2011.09.006. Epub 2011 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 22033151]

McGrath EE, Blades Z, Anderson PB. Chylothorax: aetiology, diagnosis and therapeutic options. Respiratory medicine. 2010 Jan:104(1):1-8. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2009.08.010. Epub 2009 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 19766473]

Wemyss-Holden SA, Launois B, Maddern GJ. Management of thoracic duct injuries after oesophagectomy. The British journal of surgery. 2001 Nov:88(11):1442-8 [PubMed PMID: 11683738]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaldonado F, Cartin-Ceba R, Hawkins FJ, Ryu JH. Medical and surgical management of chylothorax and associated outcomes. The American journal of the medical sciences. 2010 Apr:339(4):314-8. doi: 10.1097/MAJ.0b013e3181cdcd6c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20124878]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDoerr CH, Miller DL, Ryu JH. Chylothorax. Seminars in respiratory and critical care medicine. 2001 Dec:22(6):617-26 [PubMed PMID: 16088705]

Maldonado F, Hawkins FJ, Daniels CE, Doerr CH, Decker PA, Ryu JH. Pleural fluid characteristics of chylothorax. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 2009 Feb:84(2):129-33. doi: 10.4065/84.2.129. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19181646]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceThaler MA, Bietenbeck A, Schulz C, Luppa PB. Establishment of triglyceride cut-off values to detect chylous ascites and pleural effusions. Clinical biochemistry. 2017 Feb:50(3):134-138. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2016.10.008. Epub 2016 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 27750038]

Brito C, Vilela P. Near infra-red fluorescence-guidance for percutaneous sclerotherapy of thoracic duct leak. American journal of otolaryngology. 2020 Jul-Aug:41(4):102463. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2020.102463. Epub 2020 Mar 17 [PubMed PMID: 32229044]

Moussa AM, Maybody M, Gonzalez-Aguirre AJ, Buicko JL, Shaha AR, Santos E. Thoracic Duct Embolization in Post-neck Dissection Chylous Leakage: A Case Series of Six Patients and Review of the Literature. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2020 Jun:43(6):931-937. doi: 10.1007/s00270-020-02475-9. Epub 2020 Apr 27 [PubMed PMID: 32342160]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceScorza LB, Goldstein BJ, Mahraj RP. Modern management of chylous leak following head and neck surgery: a discussion of percutaneous lymphangiography-guided cannulation and embolization of the thoracic duct. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2008 Dec:41(6):1231-40, xi. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2008.06.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19040982]

Zabeck H, Muley T, Dienemann H, Hoffmann H. Management of chylothorax in adults: when is surgery indicated? The Thoracic and cardiovascular surgeon. 2011 Jun:59(4):243-6. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1250374. Epub 2011 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 21425049]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNair SK, Petko M, Hayward MP. Aetiology and management of chylothorax in adults. European journal of cardio-thoracic surgery : official journal of the European Association for Cardio-thoracic Surgery. 2007 Aug:32(2):362-9 [PubMed PMID: 17580118]

Chen E, Itkin M. Thoracic duct embolization for chylous leaks. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2011 Mar:28(1):63-74. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1273941. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22379277]

Kim SK, Thompson RE, Guevara CJ, Ushinsky A, Ramaswamy RS. Intranodal Lymphangiography with Thoracic Duct Embolization for Treatment of Chyle Leak after Thoracic Outlet Decompression Surgery. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2020 May:31(5):795-800. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2020.02.006. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32359526]

Drabkin M, Maybody M, Solomon N, Kishore S, Santos E. Combined antegrade and retrograde thoracic duct embolization for complete transection of the thoracic duct. Radiology case reports. 2020 Jul:15(7):929-932. doi: 10.1016/j.radcr.2020.04.035. Epub 2020 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 32419889]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKariya S, Nakatani M, Yoshida R, Ueno Y, Komemushi A, Tanigawa N. Embolization for Thoracic Duct Collateral Leakage in High-Output Chylothorax After Thoracic Surgery. Cardiovascular and interventional radiology. 2017 Jan:40(1):55-60. doi: 10.1007/s00270-016-1472-5. Epub 2016 Oct 14 [PubMed PMID: 27743087]

Van Natta TL, Nguyen AT, Benharash P, French SW. Thoracoscopic thoracic duct ligation for persistent cervical chyle leak: utility of immediate pathologic confirmation. JSLS : Journal of the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. 2009 Jul-Sep:13(3):430-2 [PubMed PMID: 19793489]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceW A Aziz WA, Rossaak JI. A unique approach to thoracic duct leak after esophagectomy. Surgical laparoscopy, endoscopy & percutaneous techniques. 2014 Aug:24(4):e155-6. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182950131. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25077645]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceJarman PR, Whyte MK, Sabroe I, Hughes JM. Sarcoidosis presenting with chylothorax. Thorax. 1995 Dec:50(12):1324-5 [PubMed PMID: 8553312]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGraham DD, McGahren ED, Tribble CG, Daniel TM, Rodgers BM. Use of video-assisted thoracic surgery in the treatment of chylothorax. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 1994 Jun:57(6):1507-11; discussion 1511-2 [PubMed PMID: 8010794]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceArtemiou O, Marta GM, Klepetko W, Wolner E, Müller MR. Pleurovenous shunting in the treatment of nonmalignant pleural effusion. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2003 Jul:76(1):231-3 [PubMed PMID: 12842547]

Taghinia AH, Upton J, Trenor CC 3rd, Alomari AI, Lillis AP, Shaikh R, Burrows PE, Fishman SJ. Lymphaticovenous bypass of the thoracic duct for the treatment of chylous leak in central conducting lymphatic anomalies. Journal of pediatric surgery. 2019 Mar:54(3):562-568. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2018.08.056. Epub 2018 Sep 9 [PubMed PMID: 30292452]

Breaux JR, Marks C. Chylothorax causing reversible T-cell depletion. The Journal of trauma. 1988 May:28(5):705-7 [PubMed PMID: 3259269]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence