Introduction

The development and widespread utilization of the nasoseptal flap has revolutionized anterior skull base reconstruction. Before the description of the nasoseptal flap in 2006, other local vascularized flaps such as the pericranial or temporoparietal fascia flaps were utilized and conveyed potentially unnecessary morbidity to patients. Reconstruction of the anterior skull base does not always require a vascularized tissue flap and can often be achieved with non-vascularized autologous or synthetic grafts. However, large skull base defects involving high-flow cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leaks require vascularized tissue reconstruction to avoid post-operative CSF leak and resultant complications. The nasoseptal flap utilizes mucosa based on a vascular pedicle within the nasal cavity that minimizes morbidity and maximizes success for anterior skull base surgical procedures.[1]

The nasoseptal flap, also known as the Hadad-Bassagasteguy flap (HB flap), was developed at the University of Rosario, Argentina, and the University of Pittsburgh and was first described in 2006.[2] Since then, there have been many theorized augmentations, proposed expansions, and enhanced indications for its use.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The nasal septum is the midline supporting structure of the nose and nasal cavity. There are four major components of the nasal septum: the maxillary crest, the vomer, the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone, and the quadrangular cartilage. The septum rests atom the maxillary spine and columellar skin inferiorly, the nasal bones, nasal cartilages, and scroll dorsally, and the entry of the nasopharynx posteriorly, spanning the entire nasal cavity. The bony and cartilaginous components of the bone are covered with periosteum and perichondrium, respectively, and the entire septum is lined with mucosa. The mucosa of the nasal septum has a robust vascular supply. The mucosa consists of pseudostratified columnar epithelium.[3][4] The major contributors to the vascular supply of the septum are the sphenopalatine, posterior septal, and greater palatine arteries, with contributions from the anterior and posterior ethmoidal arteries and coronary branch of the facial artery.[5][6]

The nasoseptal flap is a pedicled flap based on the nasoseptal artery, a branch of the posterior septal artery which originates from the sphenopalatine branch of the internal maxillary artery.[1] The nasoseptal artery enters the nasal septum between the superior border of the choana and the inferior border of the sphenoid ostium. The total length of the nasoseptal flap has been variably described at between 5.2 and 8.6 cm in length, and its width is similarly variable at 3.0 to 4.5 cm in adults. The standard HB nasoseptal flap is bounded by the borders of the nasal septum as previously described (maxillary and palatine crest, posterior septum, nasal dorsum) while sparing the segment of pedicle entry inferior to the sphenoid os to protect the pedicle. Various modifications to the nasoseptal flap have been described.[7][8] One of the most commonly used modifications to add additional tissue to the nasoseptal flap to reconstruct large skull base defects involves including the nasal floor and potentially the lateral nasal wall.[9]

While the mucosa and perichondrium are elevated off of the bony and cartilaginous septum, the bare areas of the nasal septal cartilage and bone will re-mucosalize provided the contralateral side is intact. The superior most aspect of the nasal septum acts not only to moisten and line the nasal cavity but also to aid in olfaction. The superior-most 1 to 2 cm of nasal septal mucosa are olfactory epithelium and contain receptors and nerves of the first cranial nerve.[6] The caudal portion of the septum contains a small indentation easily seen in many patients called the vomeronasal organ or Jacobson’s organ, which is thought to be a vestigial organ that has debated clinical significance.[10]

Indications

Traditionally, the nasoseptal flap was used to reconstruct large bony and dural defects of the anterior and ventral skull base following skull base surgery. In the last two decades, the indications for nasoseptal flap have broadened somewhat, and the efficacy of these strategies is under investigation.

In the span of the skull base defects, the nasoseptal flap can extend to cover surgical approaches from the cribriform to the clivus.[4] Recent studies have explored using the nasoseptal flap in the nasal cavity and skull base reconstruction and the oral cavity and oropharyngeal reconstruction following transoral robotic surgery (TORS).[11] In these studies, the nasoseptal flap has been tunneled through the palate to reconstruct soft tissue defects overlying the mandible, ICA, and as far distal as the vallecula.[12]

Contraindications

In certain patient populations, the nasoseptal flap is unavailable or ill-advised. Many extensive sinonasal tumors extend into the septal mucosa or sphenopalatine artery and branches, rendering it non-viable. Prior surgical history can be a contraindication in the case of posterior septectomy, sphenoid sinus surgery, and SPA ligation. Notably, prior uncomplicated septoplasty is not a contraindication to a nasoseptal flap.[5]

When an ipsilateral nasoseptal flap is contraindicated, there are many alternatives. Often a contralateral nasoseptal flap can be utilized.

Alternatives to nasoseptal flaps include inferior and middle turbinate flaps.[13] A temporoparietal fascia flap, pericranial flap, palatal flap, or free tissue flap may be necessary for extensive defects.[14]

Equipment

While certain equipment and setup details are heavily dependent on surgeon preference, the procedure is well described and reproduced with standard equipment. The room should be set up like that for any standard endoscopic sinus or skull base procedure. Total Intravenous Anesthesia (TIVA) is appropriate if permitted by patient comorbidities and the anesthesia provider and can improve visualization.[15] The patient can be placed in reverse Trendelenburg position to facilitate hemostasis and a clear surgical field.[16]

While a variety of endoscopes should be available, the flap is typically elevated with visualization provided by a 0 or 30-degree endoscope. An endoscopic monopolar electrocautery instrument with a needle-tip at a 45-degree bend provides ergonomic and precise incisions with simultaneous hemostasis. A Cottle elevator, micro-scissor, ball-tip probe, curette, curved olive-tip suction, through-cutting forceps (both straight and angled), and Blakesley forceps (both straight and angled) should be readily available and are typically found on a standard Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery (FESS) tray. These instruments allow for atraumatic handling and refining of the flap as it is raised.

A variety of synthetic, autologous, and donor materials can be used for underlay and support the position of the flap. Artificial dura mater, autologous fat and fascia, and absorbable packing can be used variably to support the flap. Often xeroform gauze or a Foley balloon is placed to support the graft and ancillary materials in the post-surgical recovery period. Ultimately, many of the instruments and materials utilized are based on surgeon preference.[17]

Personnel

A successful nasoseptal flap raise and inlay depends on a well-equipped and practiced surgical team. A standard framework of OR circulating nurse, scrub technician, anesthesia provider, and experienced endoscopic sinus and skull base surgeon is critical. The nasoseptal flap is often performed by an otolaryngologist fellowship-trained in rhinology and anterior skull base surgery; however, many neurosurgeons are competent and trained in both the elevation and inset of the nasoseptal flap. The roles of lead, assisting, or consulting surgeon can vary based on the case, location, and hospital protocol.[5] If the planned approach involves various materials, representatives familiar with their applications and limitations should be physically or virtually available to ensure appropriate use.

Preparation

Preparation for performing a nasoseptal flap begins with detailed patient history and physical exam, including an endoscopic nasal exam in the office setting before surgery. A focused history should be performed, including a discussion of the reasons for surgery, including the history of present illness. Prior surgeries, including any endonasal procedures, should be discussed.

A full head and neck physical exam should be performed, followed by an endoscopic endonasal examination. Rigid nasal endoscopic examination is preferred over flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy. The septum should be evaluated bilaterally for any evidence of prior surgery and deviation, perforation, or mucosal abnormalities. It is important to assess the involvement of the septum with the tumor as this may affect reconstructive options.

As with any neurosurgical or sinus procedure, appropriate imaging is critical for surgical preparation and imaging-based intraoperative navigation. CT is the imaging modality of choice for otolaryngologists performing sinus surgery, but MRI is often used for intracranial and skull base lesions and therefore used preferentially by neurosurgeons. Combining the two modalities is often preferred for appropriate skull base surgery preparation. Pre-operative imaging, thorough pre-operative medical and surgical history, and a pre-operative nasal endoscopic exam are critical for identifying possible challenges and contraindications to using the nasoseptal flap for reconstruction. Patients should be counseled to cease the use of all intranasal medications and substances pre-operatively as these can affect the integrity of the septal mucosa. Any potential sources of trauma, including new piercings, should be avoided.[5]

Because the case is clean-contaminated, as with all sinonasal surgery, no cleansing of the nasal cavity or external nose is warranted. The vibrissae of the nasal vestibule should be trimmed to avoid the collection of blood or secretions, which can dirty the endoscope and ultimately delay or complicate the procedure. The patient should be draped as appropriate for the ablative portion of the procedure and navigation registered after that.[18]

Technique or Treatment

The procedure should begin with nasal decongestion with the medication of choice (0.05% oxymetazoline, 4% cocaine, or 1% phenylephrine). Local anesthesia is usually infiltrated within the nasal septum on the desired side. Out-fracture of the inferior turbinates with a Freer or Boise elevator allows for adequate instrumentation in most patients. Classically, Hadad and Bassagetuessy describe resecting the middle turbinate on the ipsilateral side for ease of access, though outfracture of the middle turbinate may be adequate.[2]

The area of the anticipated defect is then measured and the extent of the flap planned. The dimensions of the septal flap can be extended caudally to the border of the membranous septum, variably through the nasal floor as lateral as the inferior meatus and cranially to the dorsum. Caution must be taken to avoid violating the olfactory epithelium in taking mucosa cranially. Still, the risk of adverse olfactory side effects must be weighed with the need for additional flap area. Before incising the flap, a skin marker can be used to color the mucosal side of the flap to aid in identification at the time of insetting the flap.

A standard dimension for the nasal flap involves two parallel incisions: one over the maxillary crest and another 1 to 2 cm below the superior aspect of the nasal septum to avoid the olfactory epithelium. Anteriorly the parallel incisions are joined with a perpendicular incision. The posterior incisions are the most critical as they are near the vascular pedicle. Superiorly, the incision is extended laterally over the rostrum of the sphenoid sinus at the level of the natural ostium; inferiorly, the incision is carried along the posterior edge of the septum and along the edge of the choana; this preserves the posterior septal artery as the pedicle of the flap.[5]

Elevation of the flap is usually performed with a Cottle elevator, Freer elevator, or suction-Freer elevator beginning at the most caudal and anterior aspect in a submuchopericondrial plane. Before elevating, it is best to ensure that all planned incisions are complete, as providing tension for these cuts will be more challenging as the flap is raised.[2] When raising the nasal floor and portions of the lateral nasal wall, it can be helpful to elevate these areas first. In addition, the posterior septal mucosa should be elevated, and then the flap elevated anteriorly to posteriorly.

As the flap is raised posteriorly, caution should not injure the pedicle overlying the sphenoid rostrum. Once raised, the flap should be tucked away for safekeeping (most commonly in the nasopharynx, although the maxillary sinus has been described if an antrostomy has been performed). When ready to reconstruct the skull base, it can be withdrawn and replaced along the septum to ensure appropriate orientation and avoid torsion.[5]

The reconstruction of the defect is then case-dependent and surgeon-dependent. It can utilize many autologous grafts, synthetic materials, and local or free flaps depending on the degree of dural and extradural reconstruction needed. After placing the nasoseptal flap into the defect, absorbable packing is placed, and xeroform gauze or a Foley balloon is often used to support the packing. Care should be taken to avoid overinflating as this can displace the flap within the cranial vault or out of the defect.

A contralateral, anteriorly based septal flap can be used to cover the septal donor site and decrease surgical morbidity from the nasoseptal flap harvest. However, usage of this technique "burns" the contralateral nasoseptal flap. This must be carefully considered before use.

Complications

The nasoseptal flap has been widely embraced by the skull base surgical community as it has broad indications, high success rates, and low complication rates. Early concerns about its use in children have been assuaged. It has been identified as a safe option for skull base reconstruction with no evidence of adverse effects on craniofacial development.[19]

In general, very few complications of the nasoseptal flap have been described. In their 44 patients Drs. Hadad and Bassagasteguy described no consistently observed complications with one episode of CSF leak, one episode of epistaxis requiring cautery, and a few cases of asymptomatic synechiae. The CSF leak was resolved in all cases, the flap was preserved and successful, and the septum was re-mucosalized without perforation.

An Australian prospective cohort study sought to identify changes in quality of life after utilizing the nasoseptal flap for skull base reconstruction.[20] Castle-Kirsbaum et al. identified a statistically significant decrease in Sinonasal Outcome Test (SNOT) and Anterior Skull Base Questionnaire (ASBQ) scores in the immediate postoperative period compared to those who underwent other methods of reconstruction. These patients also experienced increased otalgia and hyposmia compared to the controls. However, these symptoms and score differences resolved by six weeks postoperatively, demonstrating no significant long-term differences among patients with nasoseptal flap surgery. Other studies have suggested persistent mild hyposmia with a statistically significant decrease in UPSIT scores for as long as six months postoperatively.[21]

Clinical Significance

Hadad and Bassagasteguy’s description of the nasoseptal flap in 2006 is a landmark publication in anterior skull base surgery. The flap is now regarded as the workhorse of anterior skull base reconstruction and is by far the most versatile option for the endoscopic skull base surgeon, especially when combined with other local flaps. Utilization of the nasoseptal flap has significantly decreased morbidity for patients who would otherwise require free flap reconstruction or external approaches for other craniofacial-based local flaps.[22]

Perhaps the greatest clinical significance of the nasoseptal flap lies in its reduction of CSF leak. In the early days of endoscopic endonasal approach (EEA), CSF leak was reportedly as high as 24%; however, recent studies suggest that with the nasoseptal flap, CSF leaks resulting from EEA are as low as 3%.[23]

The indications for this flap are ever-expanding as more surgeons and specialties begin to utilize it. Reconstruction of the palate and pharynx are strategies that have only yet to be explored and combined with other local pharyngeal, palatal, and buccal flaps.[11]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The nasoseptal flap is an increasingly common technique in anterior skull base reconstruction. It is often a part of a multidisciplinary surgical team which can include counseling from otolaryngology, neurosurgery, ophthalmology, medical oncology, radiation oncology, neuroradiology, and endocrinology. As such, clear lines of communication must be maintained between providers and specialty teams regarding consensus on surgical planning and counseling. Although the procedure confers low morbidity and low risk of complications, all aspects of the risks, benefits, and alternatives must be discussed with the patient to maintain informed consent. When many surgical teams are involved, these discussions are at risk of being omitted if it is assumed that other medical teams have already performed them. Clearly outlining surgeon roles and erring on the side of redundancy will ensure that the patient is appropriately counseled about hyposmia, septal perforation, CSF leak, and meningitis.

Discussions between all involved surgical and medical providers are critical given the differences in training and surgical approach to ensure no contraindications or foreseeable intraoperative complications are overlooked. Review of the case and imaging at a multidisciplinary tumor board provides optimal care for these complex patients. It allows for discussion of adjuvant therapy, clinical trials, and novel planned approaches. Multidisciplinary tumor boards have been linked to improved outcomes for patients and as much as a 98% increase in adherence to clinical practice guidelines.[24]

Media

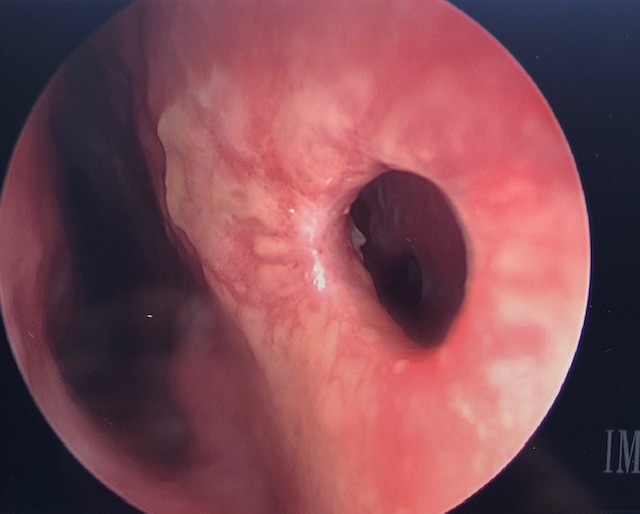

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sigler AC, D'Anza B, Lobo BC, Woodard TD, Recinos PF, Sindwani R. Endoscopic Skull Base Reconstruction: An Evolution of Materials and Methods. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2017 Jun:50(3):643-653. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2017.01.015. Epub 2017 Mar 31 [PubMed PMID: 28372814]

Hadad G, Bassagasteguy L, Carrau RL, Mataza JC, Kassam A, Snyderman CH, Mintz A. A novel reconstructive technique after endoscopic expanded endonasal approaches: vascular pedicle nasoseptal flap. The Laryngoscope. 2006 Oct:116(10):1882-6 [PubMed PMID: 17003708]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWake M, Takeno S, Hawke M. The early development of sino-nasal mucosa. The Laryngoscope. 1994 Jul:104(7):850-5 [PubMed PMID: 8022249]

Pinheiro-Neto CD,Prevedello DM,Carrau RL,Snyderman CH,Mintz A,Gardner P,Kassam A, Improving the design of the pedicled nasoseptal flap for skull base reconstruction: a radioanatomic study. The Laryngoscope. 2007 Sep; [PubMed PMID: 17597630]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReuter G, Bouchain O, Demanez L, Scholtes F, Martin D. Skull base reconstruction with pedicled nasoseptal flap: Technique, indications, and limitations. Journal of cranio-maxillo-facial surgery : official publication of the European Association for Cranio-Maxillo-Facial Surgery. 2019 Jan:47(1):29-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jcms.2018.11.012. Epub 2018 Nov 16 [PubMed PMID: 30527383]

Gras-Cabrerizo JR, Gras-Albert JR, Monjas-Canovas I, García-Garrigós E, Montserrat-Gili JR, Sánchez del Campo F, Kolanczak K, Massegur-Solench H. [Pedicle flaps based on the sphenopalatine artery: anatomical and surgical study]. Acta otorrinolaringologica espanola. 2014 Jul-Aug:65(4):242-8. doi: 10.1016/j.otorri.2014.02.002. Epub 2014 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 24713093]

Bassett E, Farag A, Iloreta A, Farrell C, Evans J, Rosen M, Singh A, Nyquist G. The extended nasoseptal flap for coverage of large cranial base defects. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2016 Nov:6(11):1113-1116. doi: 10.1002/alr.21778. Epub 2016 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 27546484]

Rivera-Serrano CM, Snyderman CH, Gardner P, Prevedello D, Wheless S, Kassam AB, Carrau RL, Germanwala A, Zanation A. Nasoseptal "rescue" flap: a novel modification of the nasoseptal flap technique for pituitary surgery. The Laryngoscope. 2011 May:121(5):990-3. doi: 10.1002/lary.21419. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21520113]

Moon JH,Kim EH,Kim SH, Various modifications of a vascularized nasoseptal flap for repair of extensive skull base dural defects. Journal of neurosurgery. 2019 Feb 8; [PubMed PMID: 30738381]

Stoyanov GS,Sapundzhiev NR,Tonchev AB, The vomeronasal organ: History, development, morphology, and functional neuroanatomy. Handbook of clinical neurology. 2021; [PubMed PMID: 34266599]

Turner MT, Geltzeiler M, Albergotti WG, Duvvuri U, Ferris RL, Kim S, Wang EW. Reconstruction of TORS oropharyngectomy defects with the nasoseptal flap via transpalatal tunnel. Journal of robotic surgery. 2020 Apr:14(2):311-316. doi: 10.1007/s11701-019-00984-5. Epub 2019 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 31183606]

Turner MT, Geltzeiler MN, Ramadan J, Moskovitz JM, Ferris RL, Wang EW, Kim S. The Nasoseptal Flap for Reconstruction of Lateral Oropharyngectomy Defects: A Clinical Series. The Laryngoscope. 2022 Jan:132(1):53-60. doi: 10.1002/lary.29660. Epub 2021 Jun 9 [PubMed PMID: 34106472]

Ruffner R, Pereira MC, Patel V, Peris-Celda M, Pinheiro-Neto CD. Inferior Meatus Mucosal Flap for Septal Reconstruction and Resurfacing After Nasoseptal Flap Harvest. The Laryngoscope. 2021 May:131(5):952-955. doi: 10.1002/lary.29029. Epub 2020 Sep 1 [PubMed PMID: 32869861]

Patel MR,Stadler ME,Snyderman CH,Carrau RL,Kassam AB,Germanwala AV,Gardner P,Zanation AM, How to choose? Endoscopic skull base reconstructive options and limitations. Skull base : official journal of North American Skull Base Society ... [et al.]. 2010 Nov [PubMed PMID: 21772795]

Moffatt DC, McQuitty RA, Wright AE, Kamucheka TS, Haider AL, Chaaban MR. Evaluating the Role of Anesthesia on Intraoperative Blood Loss and Visibility during Endoscopic Sinus Surgery: A Meta-analysis. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2021 Sep:35(5):674-684. doi: 10.1177/1945892421989155. Epub 2021 Jan 21 [PubMed PMID: 33478255]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceYang W, Wang G, Li H, Yan X, Ren Y, Wang Y, Hu H, Song X, Wan Y, Wang C, Lou H, Huang Q, Wang X, Zhang L. The 15° reverse Trendelenburg position can improve visualization without impacting cerebral oxygenation in endoscopic sinus surgery-A prospective, randomized study. International forum of allergy & rhinology. 2021 Jun:11(6):993-1000. doi: 10.1002/alr.22734. Epub 2020 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 33283449]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJiam NT, David AP, Formeister EJ, Gurrola J 2nd, Aghi M, Theodosopoulos P, Villanueva-Meyer J, McDermott MW, El-Sayed IH. Presentation and management of post-operative cerebrospinal fluid leaks after sphenoclival expanded endonasal surgery: A single institution experience. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2021 Sep:91():13-19. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2021.06.036. Epub 2021 Jun 27 [PubMed PMID: 34373017]

Passacantilli E, Lapadula G, Caporlingua F, Anichini G, Giovannetti F, Santoro A, Lenzi J. Preparation of nasoseptal flap in trans-sphenoidal surgery using 2-μ thulium laser: technical note. Photomedicine and laser surgery. 2015 Apr:33(4):220-3. doi: 10.1089/pho.2014.3847. Epub 2015 Mar 12 [PubMed PMID: 25764356]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBen-Ari O,Wengier A,Ringel B,Carmel Neiderman NN,Ram Z,Margalit N,Fliss DM,Abergel A, Nasoseptal Flap for Skull Base Reconstruction in Children. Journal of neurological surgery. Part B, Skull base. 2018 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 29404239]

Castle-Kirszbaum M,Wang YY,King J,Uren B,Dixon B,Zhao YC,Lim KZ,Goldschlager T, Patient Wellbeing and Quality of Life After Nasoseptal Flap Closure for Endoscopic Skull Base Reconstruction. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2020 Apr; [PubMed PMID: 32019727]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRotenberg BW, Saunders S, Duggal N. Olfactory outcomes after endoscopic transsphenoidal pituitary surgery. The Laryngoscope. 2011 Aug:121(8):1611-3. doi: 10.1002/lary.21890. Epub 2011 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 21647916]

Zanation AM, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, Germanwala AV, Gardner PA, Prevedello DM, Kassam AB. Nasoseptal flap reconstruction of high flow intraoperative cerebral spinal fluid leaks during endoscopic skull base surgery. American journal of rhinology & allergy. 2009 Sep-Oct:23(5):518-21. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3378. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19807986]

Singh C, Shah N. Posterior nasoseptal flap in the reconstruction of skull base defects following endonasal surgery. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2019 May:133(5):380-385. doi: 10.1017/S0022215119000926. Epub 2019 May 9 [PubMed PMID: 31070119]

Rothweiler R,Metzger MC,Voss PJ,Beck J,Schmelzeisen R, Interdisciplinary management of skull base surgery. Journal of oral biology and craniofacial research. 2021 Oct-Dec; [PubMed PMID: 34567964]