Introduction

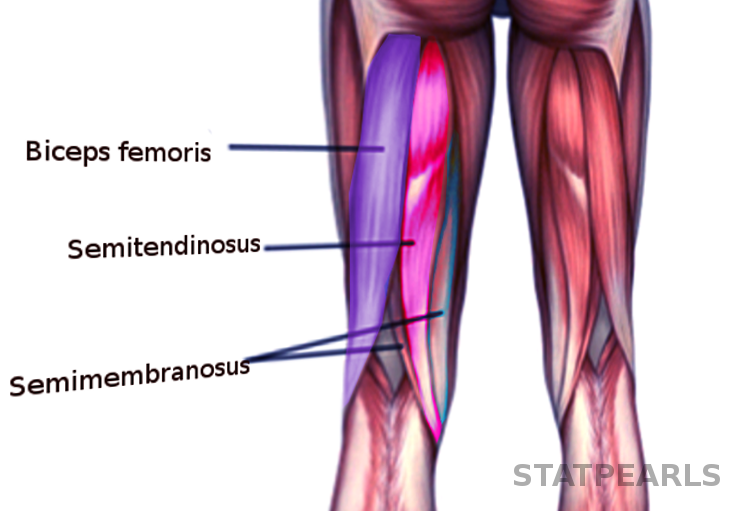

Hamstring muscles comprise the three major muscles of the posterior aspect of the thigh. These include the semimembranous as the medial most, long and short heads of the biceps femoris as the lateral most, and semitendinosus in between. These groups of muscles are clinically significant as they are highly susceptible to injury, especially in the athletes.[1] The semimembranosus and long head of the biceps femoris have a common origin on the posterolateral aspect of the ischial tuberosity while semitendinosus has an origin on the anterolateral part of the ischial tuberosity. The short head of biceps has origin medial to the linea aspera on the distal aspect of the posterior part of the femur. Both the long and short head of biceps femoris go on to insert over the head of the fibula while semimembranosus inserts over the medial condyle of the tibia. Semitendinosus inserts onto the pes anserine region on the medial part of the tibia. All the hamstring muscles traverse two joints (hip and knee) from origin to insertion except the short head of biceps femoris, which only traverses knee joint from its origin to insertion. The main function of the hamstring muscles is flexion at the knee joint and extension at the hip joint. Biceps femoris also helps in the external rotation of the hip while semimembranosus and semitendinosus help in the internal rotation of the hip joint.

Hamstring injuries mostly occur while players are running or sprinting. These groups of muscles are particularly susceptible to injury due to their anatomic arrangement. Also, their mechanism of action over two joints (knee and hip) that occur together with opposing effects on the hamstring length makes them vulnerable to injury. Also, their key role in deceleration while walking, running, and making acute changes in direction at high speed, makes them more prone to getting injured. Hamstrings bear the major strain during the phase of motion when they transition from decelerating the extension of the knee to extending the hip joint. During this rapid transition of functional biomechanics of these muscles, they are most vulnerable to injury.[2] Besides this, dual nerve supply of two heads of biceps femoris leading to asynchronous stimulation as well as an anatomical variance of attachment of its two heads makes it more commonly injured hamstring.[3]

Grading of Injury

- Grade 1: Mild pain or swelling, non-appreciable tissue disruption, no or minimal loss of function

- Grade 2: Identifiable partial disruption of tissue with moderate pain and swelling, leading to loss of function.

- Grade 3: Complete disruption or tear of the musculotendinous unit with severe pain and swelling and lack of function.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There have been some studies done to highlight the etiologies and risk factors associated with a hamstring injury. All the studies tend to suggest hamstring injury has a multifactorial etiology. Interaction among various risk factors is of paramount significance when considering the etiology of this type of muscle injury. A previous hamstring injury, older age, and peak quadriceps torque are strongly associated with the risk of a hamstring injury. Ethnicity, particularly African and Aboriginal origin and a higher level of competitiveness, have also been found to be associated with a higher incidence of a hamstring injury.[5][6] Other risk factors like hamstring flexibility, the weight of the athlete, hip flexor, quadriceps flexibility, and hamstring peak torque need further study to be proven as potential risk factors.[6]

A university study performed by eliminating the previous history of a hamstring strain concluded that high-speed running and maximum stretch of the hamstring during contact sports, hurdle jumping, falling, or dancing are associated with an increased risk of an injury.[7] In a Union of European Football Associations (UEFA) study analyzing the risk of hamstring injury in professional soccer players, previous hamstring injury had a significant association with increasing the future hamstring injury while age didn't show significant association. Injury risk decreased in goalkeepers compared to the outfield players, injury decreased in away matches compared to the home matches, and more injury rates were seen during the regular season compared to the pre-season.

The British Medical Journal published an article with a prospective study done in 100 professional soccer players, which showed functional asymmetry of the muscles predisposed them to a higher risk of sustaining a hamstring injury.[8] Also, the incidence of hamstring injury is, most of the time, sports specific as well. Sports that require rapid acceleration and deceleration like American football, soccer, Australian rule football had more incidence of a hamstring injury. More severe injuries have been found during kicking, while a higher incidence of injuries occurs during running.[6] Likewise, high-intensity training sessions, a higher level of competitiveness, positions in play that demand more running (e.g., wide receiver in American football) are associated with more hamstring injuries.[3][9]

Epidemiology

Studies showed hamstring injury peaks at 16 to 25 years of age. It is mostly related to sports where hamstrings bear the most burden, with a rapid transition of its functional biomechanics at high speed like sprinting, soccer, football, track and field sports.[10] A 13-year study done by UEFA among the elite soccer clubs of Europe found an annual 2.3% year on year increase in hamstring injury during the study. In comparison to the training-related injuries, the study showed an overall 9 times higher rate of injuries during the matches.[11] An FC Barcelona study done between July 2007 through June 2010 among its 1157 young athletes with an average age of 13.56 years found that injury was less prevalent in young athletes compared to the older ones. The average time lost from play was 21 days. In the case of avulsion from the ischium, the average days away from the play was 43.4 days.[12] One NFL study done over 10 years showed more than 50% injury during the preseason with mostly in positions like defensive secondary and wide receivers that demand more speed.[9] Even in contact sports, the non-contact mechanism of injury was more common than the contact.

History and Physical

When an athlete develops an acute posterior thigh pain during a game, which makes it difficult to return to play immediately, a hamstring injury should be suspected. Acute hamstring injuries have pain with weight-bearing and an abnormal stiff-legged gait as a result of avoiding hip and knee flexion. If there is an associated complete rupture from the ischial tuberosity, pain can be localized to the proximal thigh with point tenderness at the ischial tubercle. Patients often have difficulty sitting as a result of pain at the avulsion site. Usually, proximal injuries go hand in hand with the distal strain of semimembranosus, which might divert attention.[13] Within a few days after the injury, patients usually notice the presence of ecchymosis over the buttocks and the posterior aspect of the thigh that may extend down into the leg. Some patients may present with posterior thigh dysesthesia. This clinical presentation is called gluteal sciatica. It is associated with compression of the sciatic nerve, mainly its posterior cutaneous branch. The compression could be either by a hematoma, scar tissue or retracted muscle stump. Patients with distal hamstring injuries can have a presentation similar to that of patients with proximal injuries. In addition, knee flexion could be compromised as well.[14]

Physical examination, though an important part of the initial evaluation of hamstring injury, should not be relied upon completely to determine the exact nature of the injury due to the deep location of the hamstring muscles. Localized swelling in the posterior thigh with tenderness to palpation and induration in the posterior thigh along the hamstring muscle bellies are the common examination findings. Complete rupture may have a palpable defect within the muscle substance.[15] At the time of physical examination, strength, and range of motion of the affected hamstring should be tested and compared with those on the unaffected side. Ideally, the patient should be prone, and hip positioned at 0° of extension; then, knee flexion is assessed with resistance applied at the heel, the knee being in 15°, and 90° of flexion.[16] Pain or weakness appreciated during the examination is considered a positive finding. Hip flexion and knee extension should be examined, which may be limited by pain in patients with a hamstring injury.

Evaluation

Radiographic evaluation is an important aspect of the assessment of suspected hamstring injury to determine the nature, extent, and severity of the injury. Plain radiographs are useful to rule out a bony fracture, especially the apophyseal fracture.[16] Ultrasound and MRI are the diagnostic modalities of choice.[17] Area of injury, as evidenced by edema and hemorrhage, is depicted by echotexture in ultrasound and high signal intensity in T2 weighted images in MRI.[18] Ultrasound allows dynamic assessment of the injured hamstring muscles, but its sensitivity is increased if the ultrasound is done early after injury. MRI is still the investigation of choice to assess deeper muscle injuries, to evaluate a recurrent injury, and to differentiate new injury from the residual scarring. MR imaging also provides an estimate of the rehabilitation period.[19] Though it can predict estimated time away from the sport, it cannot identify the risks for reinjury, which needs further study.

Treatment / Management

An evidence-based approach to injury management does not exist. Management is guided based on clinical experience, anecdotal evidence, and knowledge of the biological basis of tissue repair.[20] Proximal injuries are more common and manifest from strain to complete tear.(B3)

Grades I and II strains are generally managed nonoperatively with rest, ice packs, relative immobilization, and pain and inflammation management with NSAIDs and analgesics. This is followed by progressive stretching and strengthening.[21] NSAIDs are given for no more than 5 to 7 days, and glucocorticoids are not recommended.[22] Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and other growth factors do not have enough evidence to prove their use. None of these growth factors meet the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) set guidelines, mainly because of the IGF-1 content of such preparations.[23][24] In the first 3 to 5 days, the goal should be to control hemorrhage, edema, and pain. After this, progressive ambulation assisted with crutches is initiated until pain-free walking is possible. Posture control mechanisms and pelvic alignment should be considered when managing hamstring injuries.[25](A1)

For grade III, there is a belief to go for nonsurgical treatment for isolated single tendon avulsion injury with less than 2 cm of retraction. Literature review shows nonsurgical treatment for complete tendon rupture with retraction results in an unsatisfactory outcome, including the inability to resume active lifestyle/sports, chronic knee flexion weakness, mild hip extension weakness, sciatic neuralgia, pain with sitting down and deformity. Hence, for grade III injury, surgery is recommended. Acute repair is generally preferred vs. the delayed one due to the risk of scarring of the stump to the sciatic nerve. The ideal time for surgical repair is believed to be 4 to 6 weeks post-injury. There is no proven benefit of other modalities of treatment like the therapeutic ultrasound, therapeutic laser, electric stimulation, massage, and extracorporeal shock wave (ECSW) treatment.

Differential Diagnosis

Proximal Thigh

- Lumbosacral facet syndrome

- Chronic gluteal sciatic pain (hamstring syndrome)

- Lumbosacral radiculopathy

- Piriformis syndrome

- Sacroiliac joint injury

- Lumbosacral discogenic pain syndrome

- Sciatic nerve compression by inferior or superior gluteal artery aneurysm

Distal Thigh

- Deep vein thrombosis

- Baker cyst rupture

- Knee meniscus injury

- Proximal gastrocnemius injury

- Popliteus injury

Prognosis

Clinical assessment, as well as imaging studies, help to outline the factors involved in the prognosis of a hamstring injury. Patients with a grade I and II injuries or a negative MRI study, an ability to walk pain-free within 24 hours of an injury, or short muscle tear tend to have a good prognosis in recovering from the injury as demonstrated by less time to return to play. On the other hand, Grade III injury in MRI, hamstring injuries with an avulsion fracture of bones, proximal tendon injuries, injury with large and deep hematoma tend to incline towards a poor outcome from the injury and longer recovery time. An injury sustained from low-speed stretching movements has a poorer prognosis compared to the injury sustained during high-speed activities.

Complications

- Chronic hamstring pain and injury associated with too early return to play

- Reinjury related to areas of calcification and inflammation in hamstring after injury

- Hamstring syndrome - Scar formation and impingement on the sciatic nerve

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The rehab process is an important aspect of the management of hamstring injury and plays a crucial role in making the transition back to the sport. A rehabilitation program that encompasses progressive agility and stabilization of the trunk exercises are more effective than a program emphasizing the isolated hamstring muscle.[26] A Swedish study found that a rehabilitation protocol emphasizing lengthening type of exercises is more effective than a protocol containing conventional exercises in promoting the time to return to sports.[27]

A systematic review found that to speed up the process, consideration should also be given to the lumbar spine, sacroiliac, and pelvic alignment as well as posture control mechanisms. Lengthening hamstring exercises showed the fastest return to play with a lower reinjury rate compared to the conventional hamstring exercises. Treating with PRP after the injury had no proven effect on time to return to play and reinjury risk.[28] It is important to ensure the return of normal flexibility and endurance before the patient returns to play as reinjury is common due to lack of both. Also, when the injured hamstring has 90% strength compared to that of the unaffected one and a 50% to 60% hamstring-quadriceps ratio, the athlete should return to play.

Proximal injuries involving the semimembranosus and its proximal free tendon were associated with prolonged recovery time.[10] A systematic review found the factors associated with the prolonged recovery time. These were stretching type injuries, recreational type sports, a greater range of motion deficit with the hip flexed at 90°, time to the first consultation less than one week, increased pain on the visual analog scale, and less than one day to be able to walk pain-free after the injury. A rehabilitation program that comprises loading hamstring during extensive lengthening showed evidence of an early return to sport. Besides that, 4 different sessions every day of static hamstring stretching also showed promising results in decreasing time to return to play.[29]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Hamstring injury is one of the most common sports-related injuries in the competitive realm of professional sports. It is also one injury that keeps an athlete out of action for a long time and requires proper rehabilitation before returning to play. Multiple recurrences could complicate the process of rehabilitation. In athletes who are in sports involving running and sprinting as well as non-athletes like dancers, hamstring injury should be considered if they experience acute, sharp posterior thigh pain that restricts further participation in sports unless it is clinically or radiologically ruled out with certainty. It is also important to discuss with the patients about the possible length of time away from the sport. They should also be counseled about the need for surgery in severe injuries and the importance of rehabilitation and physical therapy before returning to play.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Managing the patient of hamstring injury requires proper communication and understanding of responsibilities on the part of the team involved in the management. This includes the primary provider, orthopedic surgeons, radiologist, nursing staff, pharmacist, physical and occupational therapist, and, most importantly, the patients themselves. Good coordination of care is required for proper recovery and also preventing reinjuries. If a patient comes with pain on the back of the thigh while running, sprinting, or stretching, which prevents further continuation of the activity, they should be evaluated for an acute hamstring injury. Radiologists have a key role in determining the size, nature, and extent of the injury, which will be crucial in further management of the injury. These patients should be evaluated by either sports medicine or Orthopedics to determine the need for surgical management.

Early surgical intervention gives better results than the late interventions, especially in the complete proximal avulsions of the hamstring muscle.[30] [Level 4] Generally, complete (grade III) proximal injuries and grade II and III distal hamstring injuries would require surgical repair for a better outcome. Results are promising from surgical repair of proximal injuries even after the non-operative method has been tried initially and has failed.[31]

An orthopedics consultation is of paramount significance to have a better outcome after the injury as early operative treatment gives promising results. The nursing staffs have a key role too in both non-surgical as well as surgical management. The physician assistant, nurse practitioner, if they are seeing a patient with a hamstring injury, should be able to determine when to refer to orthopedics or sports medicine and the need for operative vs. non-operative management. After proper surgical or non-surgical management, physical and occupational therapists have a crucial role in the rehabilitation, strength training, and speeding up the return to play. Studies have generally shown there is 87% strength return after 6 to 12 months post-surgery, while about 98% strength returns after more than 12 months of surgery.[32][33] The athletes should also follow the guidelines and comply with the instruction of the team involved in the care and not rush to return to play.

Media

References

Davis KW. Imaging of the hamstrings. Seminars in musculoskeletal radiology. 2008 Mar:12(1):28-41. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067935. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18382942]

Petersen J, Hölmich P. Evidence based prevention of hamstring injuries in sport. British journal of sports medicine. 2005 Jun:39(6):319-23 [PubMed PMID: 15911599]

Woods C, Hawkins RD, Maltby S, Hulse M, Thomas A, Hodson A, Football Association Medical Research Programme. The Football Association Medical Research Programme: an audit of injuries in professional football--analysis of hamstring injuries. British journal of sports medicine. 2004 Feb:38(1):36-41 [PubMed PMID: 14751943]

Kuske B, Hamilton DF, Pattle SB, Simpson AH. Patterns of Hamstring Muscle Tears in the General Population: A Systematic Review. PloS one. 2016:11(5):e0152855. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152855. Epub 2016 May 4 [PubMed PMID: 27144648]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePrior M, Guerin M, Grimmer K. An evidence-based approach to hamstring strain injury: a systematic review of the literature. Sports health. 2009 Mar:1(2):154-64 [PubMed PMID: 23015867]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFreckleton G, Pizzari T. Risk factors for hamstring muscle strain injury in sport: a systematic review and meta-analysis. British journal of sports medicine. 2013 Apr:47(6):351-8. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2011-090664. Epub 2012 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 22763118]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTokutake G, Kuramochi R, Murata Y, Enoki S, Koto Y, Shimizu T. The Risk Factors of Hamstring Strain Injury Induced by High-Speed Running. Journal of sports science & medicine. 2018 Dec:17(4):650-655 [PubMed PMID: 30479534]

Fousekis K,Tsepis E,Poulmedis P,Athanasopoulos S,Vagenas G, Intrinsic risk factors of non-contact quadriceps and hamstring strains in soccer: a prospective study of 100 professional players. British journal of sports medicine. 2011 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 21119022]

Elliott MC, Zarins B, Powell JW, Kenyon CD. Hamstring muscle strains in professional football players: a 10-year review. The American journal of sports medicine. 2011 Apr:39(4):843-50. doi: 10.1177/0363546510394647. Epub 2011 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 21335347]

Askling CM, Tengvar M, Saartok T, Thorstensson A. Proximal hamstring strains of stretching type in different sports: injury situations, clinical and magnetic resonance imaging characteristics, and return to sport. The American journal of sports medicine. 2008 Sep:36(9):1799-804. doi: 10.1177/0363546508315892. Epub 2008 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 18448581]

Ekstrand J, Waldén M, Hägglund M. Hamstring injuries have increased by 4% annually in men's professional football, since 2001: a 13-year longitudinal analysis of the UEFA Elite Club injury study. British journal of sports medicine. 2016 Jun:50(12):731-7. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095359. Epub 2016 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 26746908]

Valle X, Malliaropoulos N, Párraga Botero JD, Bikos G, Pruna R, Mónaco M, Maffulli N. Hamstring and other thigh injuries in children and young athletes. Scandinavian journal of medicine & science in sports. 2018 Dec:28(12):2630-2637. doi: 10.1111/sms.13282. Epub 2018 Sep 10 [PubMed PMID: 30120838]

Ali K, Leland JM. Hamstring strains and tears in the athlete. Clinics in sports medicine. 2012 Apr:31(2):263-72. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2011.11.001. Epub 2011 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 22341016]

Alzahrani MM, Aldebeyan S, Abduljabbar F, Martineau PA. Hamstring Injuries in Athletes: Diagnosis and Treatment. JBJS reviews. 2015 Jun 30:3(6):. pii: e5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.RVW.N.00108. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27490012]

Clanton TO,Coupe KJ, Hamstring strains in athletes: diagnosis and treatment. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1998 Jul-Aug; [PubMed PMID: 9682086]

Heiderscheit BC, Sherry MA, Silder A, Chumanov ES, Thelen DG. Hamstring strain injuries: recommendations for diagnosis, rehabilitation, and injury prevention. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2010 Feb:40(2):67-81. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3047. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20118524]

Cohen S, Bradley J. Acute proximal hamstring rupture. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2007 Jun:15(6):350-5 [PubMed PMID: 17548884]

Koulouris G, Connell D. Imaging of hamstring injuries: therapeutic implications. European radiology. 2006 Jul:16(7):1478-87 [PubMed PMID: 16514470]

Connell DA, Schneider-Kolsky ME, Hoving JL, Malara F, Buchbinder R, Koulouris G, Burke F, Bass C. Longitudinal study comparing sonographic and MRI assessments of acute and healing hamstring injuries. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2004 Oct:183(4):975-84 [PubMed PMID: 15385289]

Hoskins W, Pollard H. Hamstring injury management--Part 2: Treatment. Manual therapy. 2005 Aug:10(3):180-90 [PubMed PMID: 15993642]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRopiak CR, Bosco JA. Hamstring injuries. Bulletin of the NYU hospital for joint diseases. 2012:70(1):41-8 [PubMed PMID: 22894694]

Ford LT, DeBender J. Tendon rupture after local steroid injection. Southern medical journal. 1979 Jul:72(7):827-30 [PubMed PMID: 451692]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBorrione P, Gianfrancesco AD, Pereira MT, Pigozzi F. Platelet-rich plasma in muscle healing. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2010 Oct:89(10):854-61. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181f1c1c7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20855985]

Creaney L, Hamilton B. Growth factor delivery methods in the management of sports injuries: the state of play. British journal of sports medicine. 2008 May:42(5):314-20 [PubMed PMID: 17984193]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMason DL, Dickens V, Vail A. Rehabilitation for hamstring injuries. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2007 Jan 24:(1):CD004575 [PubMed PMID: 17253514]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSherry MA, Best TM. A comparison of 2 rehabilitation programs in the treatment of acute hamstring strains. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2004 Mar:34(3):116-25 [PubMed PMID: 15089024]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAskling CM, Tengvar M, Tarassova O, Thorstensson A. Acute hamstring injuries in Swedish elite sprinters and jumpers: a prospective randomised controlled clinical trial comparing two rehabilitation protocols. British journal of sports medicine. 2014 Apr:48(7):532-9. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093214. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24620041]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceIshøi L, Krommes K, Husted RS, Juhl CB, Thorborg K. Diagnosis, prevention and treatment of common lower extremity muscle injuries in sport - grading the evidence: a statement paper commissioned by the Danish Society of Sports Physical Therapy (DSSF). British journal of sports medicine. 2020 May:54(9):528-537. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2019-101228. Epub 2020 Jan 14 [PubMed PMID: 31937579]

Fournier-Farley C, Lamontagne M, Gendron P, Gagnon DH. Determinants of Return to Play After the Nonoperative Management of Hamstring Injuries in Athletes: A Systematic Review. The American journal of sports medicine. 2016 Aug:44(8):2166-72. doi: 10.1177/0363546515617472. Epub 2015 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 26672025]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSarimo J,Lempainen L,Mattila K,Orava S, Complete proximal hamstring avulsions: a series of 41 patients with operative treatment. The American journal of sports medicine. 2008 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 18319349]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLempainen L, Sarimo J, Heikkilä J, Mattila K, Orava S. Surgical treatment of partial tears of the proximal origin of the hamstring muscles. British journal of sports medicine. 2006 Aug:40(8):688-91 [PubMed PMID: 16790482]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSallay PI, Ballard G, Hamersly S, Schrader M. Subjective and functional outcomes following surgical repair of complete ruptures of the proximal hamstring complex. Orthopedics. 2008 Nov:31(11):1092 [PubMed PMID: 19226093]

Wood DG, Packham I, Trikha SP, Linklater J. Avulsion of the proximal hamstring origin. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 2008 Nov:90(11):2365-74. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.G.00685. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18978405]