Introduction

Philadelphia orthopedic surgeon John Rhea Barton first described a Barton fracture. It is a fracture of the distal radius which extends through the dorsal aspect of the articular surface with associated dislocation of the radiocarpal joint.[1] There is no disruption of the radiocarpal ligaments, and the articular surface of the fractured distal radius remains in contact with the proximal carpal row.[1][2]This preserved relationship between the radius and carpus is what distinguishes the Barton fracture from other types of distal radius fracture/dislocations. The distal radius fracture may involve either the volar or dorsal cortex. Volar and dorsal barton fractures are subclassified based on the fracture pattern. As compared to the dorsal rim fracture, the volar barton fracture occurs more frequently. Non-union of barton fracture is less likely because the distal radius has a large proportion of cancellous bone. On the other hand, an anatomical reduction is required as malunion and wrist arthritis are common following barton fractures.[3] The wrist's ability to deviate ulnarly for a power grab depends on the distal radius articular surface's volar and ulnar slope. The volar surface of the distal radius is comparatively flat. The volar radiocarpal ligaments originate from a ridge of the distal radial border. It's crucial to comprehend that the distal radial cortical edge slopes laterally toward the ulnar. From proximal to distal, the lunate facet's ulnar volar border slopes 3mm vertically making a difficult internal fixation. The lunate fossa appears as a teardrop sign on the lateral radiograph. Failure to support this lunate border would lead to incompetent short radiolunate ligament resulting in radiocarpal instability.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The most common mechanisms of injury vary depending on the patient population. In the pediatric and young adult population, most Barton fractures result from sporting activities and motor vehicle accidents. The most common reason for it to happen is a direct, traumatic wrist injury. Young male workers or motorcycle riders account for 70% of Barton's fracture cases. However, in the elderly, particularly women, decreased bone density from osteoporosis means that less force is needed to cause this injury. [5] Therefore, the majority of these fractures are a result of a fall while standing.

Epidemiology

The recent increase in distal radius fractures in patients of all ages is attributed to a variety of factors. Fractures in pediatric patients are most common around the time of puberty, with boys tending to suffer the injury more often than girls. The young adult population (ages 19 to 49) is the least affected by Barton fractures, with a greater predilection for males than females. In the elderly, women are more likely to be diagnosed with a Barton fracture than their male counterparts due to higher rates of osteoporosis. Volar Barton fractures make about 1.3 percent of distal radius fractures.[6]

Pathophysiology

A Barton fracture is a compression injury with a marginal shearing fracture of the distal radius. The most common cause of this injury is a fall on an outstretched, pronated wrist. The compressive force travels from the hand and wrist through the articular surface of the radius, resulting in a triangular portion of the distal radius being displaced dorsally along with the carpus.[7] Multiple stabilizing structures help to maintain the relationship between the radius and the carpal bones, including the extrinsic radiocarpal ligaments, the joint capsule, and the scaphoid and lunate fossa of the radius. The associated injuries are distal radioulnar joint disruption, Triangular Fibrocartilage Complex (TFCC) tear, scapholunate ligament injury, and volar intercalated segment instability.[8][9]

History and Physical

Patients with Barton fractures will typically present to the urgent care or emergency department with acute wrist pain, swelling, and deformity following a recent trauma. The examination may reveal ecchymosis, tenderness, and swollen wrist joint. The range of motion of the wrist joint will be limited due to pain. To rule out associated injuries and complications, the distal neurovascular status must be assessed. A younger patient commonly will describe a sporting injury or motor vehicle accident, while older patients may report a lower energy trauma such as a fall from standing. The patient typically describes a history of fall on an outstretched hand. The type of fracture depends upon the position of the wrist joint during impact e.g. volar shear fractures occur when the wrist is in palmar flexion, while dorsiflexion leads to dorsal shear fractures.

Evaluation

Initial evaluation of the Barton fracture begins with radiographs of the wrist, consisting of at least frontal and lateral views. Oblique views of the wrist often are obtained and may assist in the diagnosis. The radial height inclination, ulnar variance, and articular step are measured on an anteroposterior radiograph. Volar tilt, coronal split, and comminution are visible on lateral radiographs. The radius is 23 degrees inclined in the coronal plane and has an 11 degrees tilt in the sagittal plane. The radius height is approximately 11 mm and ulnar variance ranges from -2mm to +2mm. A radiograph of the unaffected side can be used as a benchmark to see how well all values have returned to normal ranges. An important prognostic factor for wrist arthritis and pain-free range of motion is articular congruity of the distal radius.[10] CT can be used to better evaluate anatomic detail or if radiographs are unclear. It provides information regarding the level of comminution, occult fractures, and the assessment of fracture union. MRI is not the first modality of investigation for acute settings, however, it may be utilized to evaluate for associated ligamentous or soft tissue injuries.[11]

Treatment / Management

The overall goal in the evaluation and treatment of these patients presenting with Barton fractures is to obtain sufficient pain-free motion which will allow the patient to return to their usual activities while at the same time minimizing their risk for developing early-onset osteoarthritis that will lead to disability. Traditionally, the treatment of distal radius fractures is by closed reduction and immobilization in a splint or cast, this has been and remains the treatment of choice in nondisplaced and stable distal radial fractures. [12] Due to the nature of Barton fractures and the implied dorsal displacement of the fracture, many fractures will fail conservative management; therefore, surgical treatment is the preferred option.[13][14] (B2)

The following key radiographic signs should alert the surgeon that the fracture is unstable and indicate closed reduction will be insufficient:

- Dorsal comminution greater than 50% of the lateral width of the distal radius,

- Palmar metaphyseal comminution,

- Initial dorsal tilt greater than 20 degrees, initial fragment displacement greater than 1 cm,

- Radial shortening of more than 5 mm,

- Intra-articular disruption or Barton's fracture

- An associated ulna fracture, and

- Severe osteoporosis.

Most Barton fractures are unstable and operative fixation is required. The undisplaced fractures can be managed with immobilization in a cast. While applying the cast, the wrist is slightly volar flexed in volar barton fracture and dorsiflexed in dorsal barton fracture.[15] The exceedingly fragile nature of this injury predisposes to displacement in a cast, therefore even undisplaced fractures need to be constantly monitored radiographically until union. Those who elect to forgo surgery are treated with reduction and immobilization for at least six weeks. [16]When electing to treat these patients with either operative or nonoperative therapy, it is essential to include the patient in the management decision, clearly allowing them to establish and understand the pre-management expectations. Open reduction and internal fixation are recommended for Barton's fracture due to the unstable fracture pattern and the strong pull of flexor tendons.

Volar Approach for Volar Barton's Fracture

A Volar T-buttress plate is used for the fixation of volar rim fracture. In contrast to the principle of fixation, the plate is applied on the volar surface rather than the tensile/dorsal surface due to less soft tissue irritation.[15] Henry's approach or trans-FCR approach is used to approach volar barton fracture. Henry's approach includes the interval between the flexor carpi radialis tendon and the radial artery, while the fracture is approached through the tendon sheath of the flexor carpi radialis tendon in the trans-FCR approach. The dissection is done radial to flexor carpi radialis to prevent injury to the palmar cutaneous branch of the median nerve. Flexor carpi radialis, the flexor digitorum superficialis, and profundus tendons are retracted towards the ulnar side. in order to prevent the possible denervation of the muscle, avoid radial retraction of the flexor pollicis longus. The volar radiocarpal ligaments that stabilize the wrist are preserved as the pronator quadratus is lifted off from the radial side.[17] Every effort should be made to stabilize the volar lunate facet fragment to prevent carpal subluxation and instability. This may require an extension of the volar incision that incorporates a carpal tunnel release or a separate ulnar incision is made to stabilize the lunate facet fragment.[18] A volar barton's fracture with dorsal rim fracture of the distal radius requires a well-contoured volar plate to prevent dorsal angulation of distal radius articular surface and poor wrist functional outcome.[8] Following surgery, the wrist is immobilized in a splint for five to ten days and then active wrist mobility is started.(B3)

Dorsal Approach for Dorsal Barton's Fracture

A preoperative CT scan is required for the evaluation of fracture patterns and the level of comminution. The dorsal approach is used for dorsal barton and fragment-specific fixation of distal radius fracture through the 3rd dorsal compartment. A 5-6 cm longitudinal incision is made along the lister tubercle. The extensor pollicis longus tendon is retracted radially after incising the roof of the 3rd dorsal compartment. Subperiosteal dissection is done in the 2nd and 4th dorsal compartments to expose the distal radius. [19] To prevent postoperative wrist pain, the posterior interosseous nerve is sacrificed proximally or preserved by dissecting it in a subperiosteal fashion in the 4th compartment.[20] In order to prevent radiocarpal instability, the scapholunate ligament is preserved while performing a dorsal wrist capsulotomy. The dorsal capsule is incised vertically along the skin incision. The dorsal barton fracture is reduced with traction and dorsiflexion maneuver. The dorsal buttress plate or locking plate is used to stabilize the fracture and maintain articular congruity.

K-wires have been used along with a spanning external fixator for barton fracture with a success rate of 80-90%.[21] The disadvantages of K-wire fixation are mal-reduction, tendon penetration of wires, and pin site infection. The overall success rate with the plating system is 90-95% however it is associated with wound-related complications. The long-term outcome depends upon the level of fracture comminution, joint arthrosis, and range of motion wrist exercises postoperatively.[3] If volar Barton fractures do not include carpal subluxation, closed reduction with the cast is advised. However, a 2mm articular step warrants operative fixation.[16](A1)

Differential Diagnosis

Various distal radius fractures can have similar clinical presentations and may appear radiographically similar to the Barton fracture.

- The reverse Barton fracture is an articular fracture of the distal radius with dislocation in which the articular surface of the radius remains in contact with the carpus; however, the reverse type involves the volar portion rather than the dorsal aspect of the radius.

- The Colles fracture is a fracture of the distal radius with dorsal angulation/displacement; the key differentiating finding is the lack of intraarticular extension.

- The Smith fracture can be thought of as a reverse Colles fracture with volar rather than dorsal angulation.

- The die-punch fracture is a fracture of the articular surface of the radius with depression of the lunate facet.

- The Chauffer’s fracture is an avulsion fracture of the radial styloid.

Staging

Morphological classification:[22]

- Typical Barton

- Radial Barton

- Ulnar Barton

- Comminuted Barton

Prognosis

Intraarticular fractures of the distal radius, including the Barton fracture, have a higher risk of post-traumatic arthritis than extraarticular fractures. Any articular step-off of greater than 2 millimeters can increase the likelihood of post-traumatic arthritis by almost 100%. However, most studies indicate this does not significantly affect livelihood. The population with the worst prognosis is the elderly, who tend to have higher mortality than other patients due to the limitations to activities of daily living.[23]

Complications

The treating/managing physician should be aware of the multiple injuries that can occur in association with Barton fractures and other fractures of the distal radius including tears of the triangular fibrocartilage (TFCC), traumatic acute carpal tunnel syndrome, development of compartment syndrome in the forearm at time of initial presentation, and development of complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) in the subsequent weeks and months following the initial treatment. Range-of-motion exercises for the wrist and fingers should be started as soon as possible to prevent wrist stiffness. [24]

These complications can occur following Barton's fracture: Carpal tunnel syndrome, radial nerve compression, ulnar nerve injury, complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS), post-traumatic arthritis, radiocarpal instability, malunion, distal radioulnar joint instability, flexor tendon adhesions, tendon rupture, tendinitis, tenosynovitis, trigger finger, Dupuytren's contracture, and compartment syndrome.

Surgical site infection, loss of fracture reduction, iatrogenic fracture, tendon injuries, neurovascular compromise, compartment syndrome, painful implant, and wrist stiffness are the common complications postoperatively.[25]

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

The main goal of rehabilitation is to achieve pain-free full range of motion of the wrist joint. Rehabilitation and physiotherapy are continued during three stages of treatment: splinting, mobilization, and endurance training. Full mobilization of fingers, elbow, and shoulder is advised even during splinting phase to prevent stiffness.[26] The immobilization period ranges from three weeks to six weeks. Shorter immobilization(3 weeks) leads to improved short-term outcomes while long-term results are comparable to that of 6 weeks of splinting.[27] The objectives of pain and edema management, along with improved wrist mobility are continued during the mobilization phase. Delayed immobilization leads to increased increased wrist stiffness and frequent visits to therapists. After the active and passive range of motion exercises, strengthening exercises are carried out by the therapist.[28]

Pearls and Other Issues

- The Barton fracture is a fracture of the distal radius which extends through the dorsal aspect of the articular surface with associated dislocation of the radiocarpal joint. However, since there is no disruption of the radiocarpal ligaments, the articular surface of the fractured distal radius remains in contact with the proximal carpal row.

- Radiography is the primary imaging modality in diagnosis, although CT and MRI have a role as well.

- In the younger population, males suffer the injury more often than females, typically following high-energy trauma.

- In the elderly, more women are diagnosed with Barton fractures after a fall from standing or other low-energy trauma.

- Most Barton fractures are treated surgically, though recent studies have shown little significant difference in operative versus nonoperative management in the elderly.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Patients with a Barton fracture often first present to the emergency room; hence the emergency department physician and the nurse practitioner are often the first to make the diagnosis. It is important to know that Barton fracture is frequently associated with other injuries and hence a thorough physical exam is necessary. Because conservative treatment of Barton fracture is not always satisfactory, it is important to consult with the orthopedic surgeon. Most Barton fractures are treated surgically, though recent studies have shown little significant difference in operative versus nonoperative management in the elderly. After surgery, the outcomes in young patients are good but in elderly people, the recovery can be prolonged. All patients need some type of rehabilitation after the fracture has healed. [6][29] [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

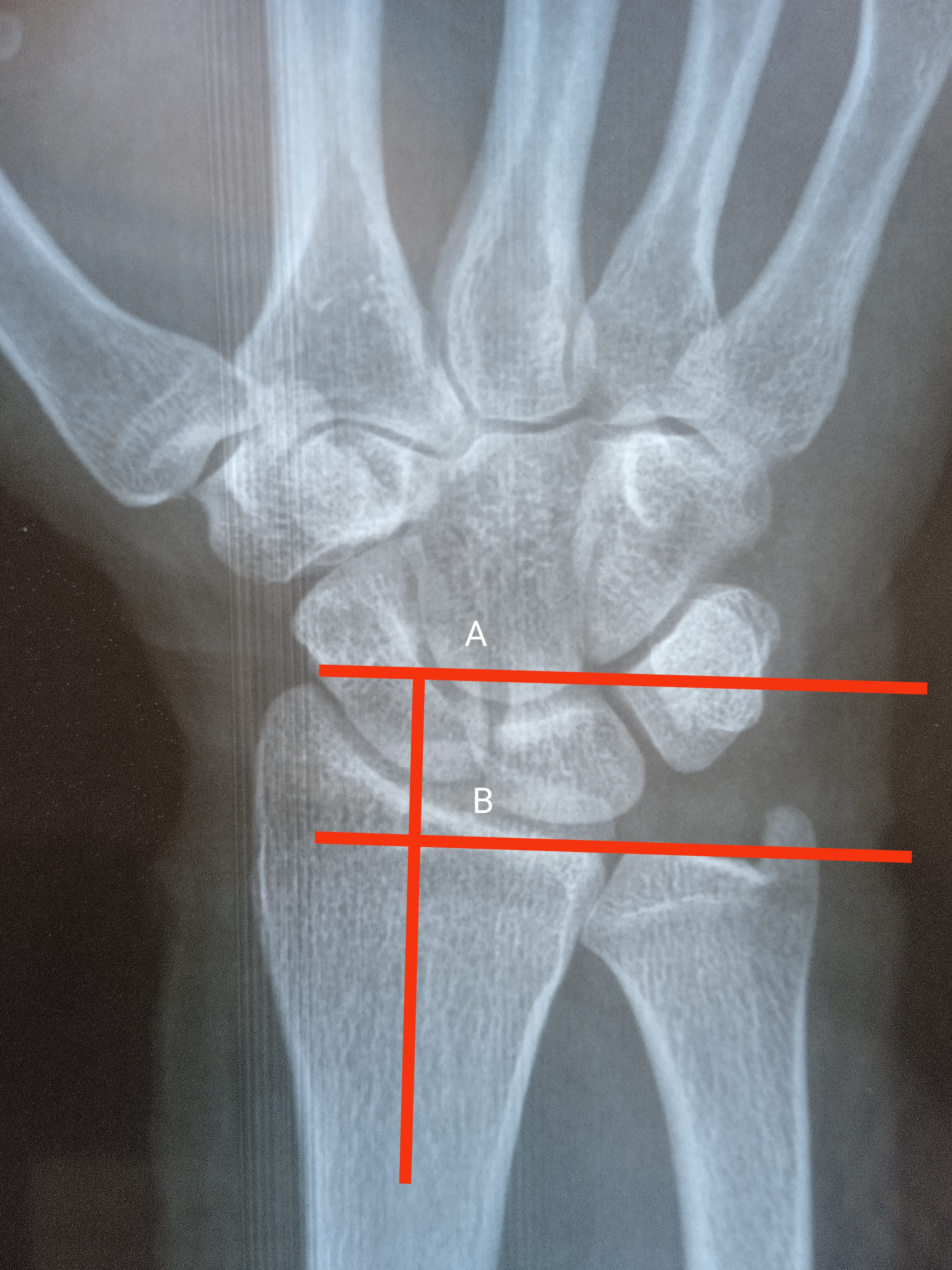

Radial Height: Both lines are drawn perpendicular to long axis of distal radius. Line A is drawn from the tip of radial styloid while the line B is present along the ulnar articular surface of distal radius. The distance of both lines is radial height. The normal value is 13mm. Contributed by Dr. Muhammad Taqi

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Wæver D, Madsen ML, Rölfing JHD, Borris LC, Henriksen M, Nagel LL, Thorninger R. Distal radius fractures are difficult to classify. Injury. 2018 Jun:49 Suppl 1():S29-S32. doi: 10.1016/S0020-1383(18)30299-7. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29929689]

Mauck BM, Swigler CW. Evidence-Based Review of Distal Radius Fractures. The Orthopedic clinics of North America. 2018 Apr:49(2):211-222. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2017.12.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29499822]

Dai MH, Wu CC, Liu HT, Wang IC, Yu CM, Wang KC, Chen CH, Jung CH. Treatment of volar Barton's fractures: comparison between two common surgical techniques. Chang Gung medical journal. 2006 Jul-Aug:29(4):388-94 [PubMed PMID: 17051836]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAndermahr J, Lozano-Calderon S, Trafton T, Crisco JJ, Ring D. The volar extension of the lunate facet of the distal radius: a quantitative anatomic study. The Journal of hand surgery. 2006 Jul-Aug:31(6):892-5 [PubMed PMID: 16843146]

Barton DW,Griffin DC,Carmouche JJ, Orthopedic surgeons' views on the osteoporosis care gap and potential solutions: survey results. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2019 Mar 6; [PubMed PMID: 30841897]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAggarwal AK, Nagi ON. Open reduction and internal fixation of volar Barton's fractures: a prospective study. Journal of orthopaedic surgery (Hong Kong). 2004 Dec:12(2):230-4 [PubMed PMID: 15621913]

Shaw R, Mandal A, Mukherjee KS, Pandey PK. An evaluation of operative management of displaced volar Barton's fractures using volar locking plate. Journal of the Indian Medical Association. 2012 Nov:110(11):782-4 [PubMed PMID: 23785911]

Harness N, Ring D, Jupiter JB. Volar Barton's fractures with concomitant dorsal fracture in older patients. The Journal of hand surgery. 2004 May:29(3):439-45 [PubMed PMID: 15140487]

Jupiter JB, Complex Articular Fractures of the Distal Radius: Classification and Management. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 1997 May; [PubMed PMID: 10797214]

Medoff RJ. Essential radiographic evaluation for distal radius fractures. Hand clinics. 2005 Aug:21(3):279-88 [PubMed PMID: 16039439]

Meena S, Sharma P, Sambharia AK, Dawar A. Fractures of distal radius: an overview. Journal of family medicine and primary care. 2014 Oct-Dec:3(4):325-32. doi: 10.4103/2249-4863.148101. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25657938]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen HQ, Wen XL, Li YM, Wen CY. [Case-control study on T-shaped locking internal fixation and external fixation for the treatment of dorsal Barton's fracture]. Zhongguo gu shang = China journal of orthopaedics and traumatology. 2015 Jun:28(6):517-20 [PubMed PMID: 26255475]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTang Z, Yang H, Chen K, Wang G, Zhu X, Qian Z. Therapeutic effects of volar anatomical plates versus locking plates for volar Barton's fractures. Orthopedics. 2012 Aug 1:35(8):e1198-203. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20120725-19. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22868605]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLiao QD, Zhong D, Yin K, Li RJ, Li KH. [Internal fixation with T type titanium plate for volar Barton's fracture]. Zhong nan da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban = Journal of Central South University. Medical sciences. 2008 Jan:33(1):74-7 [PubMed PMID: 18245909]

de Oliveira JC. Barton's fractures. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. American volume. 1973 Apr:55(3):586-94 [PubMed PMID: 4703210]

Tang WJ, Wang MY, Gong XY, An GS. [Clinical investigation of conservative treatment for volar Barton fracture]. Zhongguo gu shang = China journal of orthopaedics and traumatology. 2008 May:21(5):383-5 [PubMed PMID: 19108474]

Ilyas AM. Surgical approaches to the distal radius. Hand (New York, N.Y.). 2011 Mar:6(1):8-17. doi: 10.1007/s11552-010-9281-9. Epub 2010 Jun 22 [PubMed PMID: 22379433]

Chin KR, Jupiter JB. Wire-loop fixation of volar displaced osteochondral fractures of the distal radius. The Journal of hand surgery. 1999 May:24(3):525-33 [PubMed PMID: 10357531]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVia GG, Roebke AJ, Julka A. Dorsal Approach for Dorsal Impaction Distal Radius Fracture-Visualization, Reduction, and Fixation Made Simple. Journal of orthopaedic trauma. 2020 Aug:34 Suppl 2():S15-S16. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001829. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32639341]

Buck-Gramcko D. Denervation of the wrist joint. The Journal of hand surgery. 1977 Jan:2(1):54-61 [PubMed PMID: 839055]

Harley BJ, Scharfenberger A, Beaupre LA, Jomha N, Weber DW. Augmented external fixation versus percutaneous pinning and casting for unstable fractures of the distal radius--a prospective randomized trial. The Journal of hand surgery. 2004 Sep:29(5):815-24 [PubMed PMID: 15465230]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLu Y, Li S, Wang M. A classification and grading system for Barton fractures. International orthopaedics. 2016 Aug:40(8):1725-1734. doi: 10.1007/s00264-015-3034-x. Epub 2015 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 26566639]

Lameijer CM, Ten Duis HJ, Vroling D, Hartlief MT, El Moumni M, van der Sluis CK. Prevalence of posttraumatic arthritis following distal radius fractures in non-osteoporotic patients and the association with radiological measurements, clinician and patient-reported outcomes. Archives of orthopaedic and trauma surgery. 2018 Dec:138(12):1699-1712. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-3046-2. Epub 2018 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 30317380]

Mathews AL, Chung KC. Management of complications of distal radius fractures. Hand clinics. 2015 May:31(2):205-15. doi: 10.1016/j.hcl.2014.12.002. Epub 2015 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 25934197]

Diaz-Garcia RJ, Oda T, Shauver MJ, Chung KC. A systematic review of outcomes and complications of treating unstable distal radius fractures in the elderly. The Journal of hand surgery. 2011 May:36(5):824-35.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2011.02.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21527140]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKuo LC, Yang TH, Hsu YY, Wu PT, Lin CL, Hsu HY, Jou IM. Is progressive early digit mobilization intervention beneficial for patients with external fixation of distal radius fracture? A pilot randomized controlled trial. Clinical rehabilitation. 2013 Nov:27(11):983-93. doi: 10.1177/0269215513487391. Epub 2013 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 23787939]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBhan K, Hasan K, Pawar AS, Patel R. Rehabilitation Following Surgically Treated Distal Radius Fractures: Do Immobilization and Physiotherapy Affect the Outcome? Cureus. 2021 Jul:13(7):e16230. doi: 10.7759/cureus.16230. Epub 2021 Jul 7 [PubMed PMID: 34367829]

Ikpeze TC, Smith HC, Lee DJ, Elfar JC. Distal Radius Fracture Outcomes and Rehabilitation. Geriatric orthopaedic surgery & rehabilitation. 2016 Dec:7(4):202-205 [PubMed PMID: 27847680]

Mostafa MF. Treatment of distal radial fractures with antegrade intra-medullary Kirschner wires. Strategies in trauma and limb reconstruction. 2013 Aug:8(2):89-95. doi: 10.1007/s11751-013-0161-z. Epub 2013 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 23740182]