Introduction

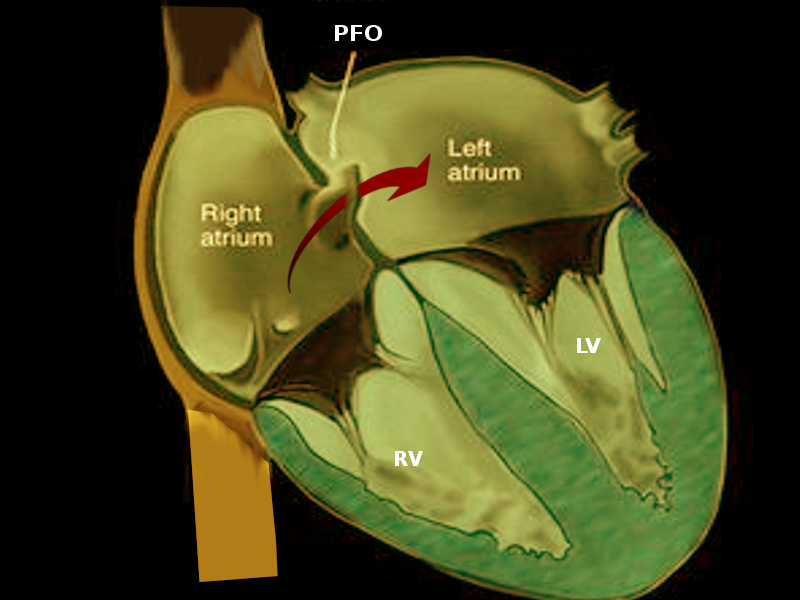

Patent foramen ovale (PFO) is part of a group of entities known as atrial septal defects and is a remnant of normal fetal anatomy. More than half of infants have PFO at 6 months of age.[1] Although it doesn't have a major clinical effect in neonates, it may persist into adulthood. Most adult patients with a PFO are asymptomatic; however, in some adults, PFO may result in an inter-atrial, right-to-left shunting of deoxygenated blood and the potential for shunting venous thromboembolism to the arterial circulation. These changes explain the pathophysiologic determinant of several conditions associated with PFO, including cryptogenic (having no other identifiable cause) stroke, decompression sickness, migraine, platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome, and acute limb ischemia secondary to emboli (See Image. Patent Foramen Ovale).[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

The foramen ovale is a tunnel-like space between the overlying septum secundum and septum primum. It closes in 75% of infants when the septum primum and secundum fuse. In utero, the foramen ovale is necessary for blood flow across the fetal atrial septum. Oxygenated blood from the placenta returns to the inferior vena cava, crosses the foramen ovale, and enters the systemic circulation. In approximately 25% of people, a PFO persists into adulthood. PFOs may be found in association with:

- Atrial septal aneurysms (a redundancy of the interatrial septum)

- Eustachian valves (a remnant of the sinus venosus valve)

- Chiari networks (filamentous strands in the right atrium)

Clinically significant PFOs result in adverse consequences by 2 mechanisms:

- Serving as a conduit for paradoxical embolization from the venous side to the systemic circulation

- Because of their tunnel-like structure and propensity for stagnant flow, they may serve as a nidus for in situ thrombus formation.[3]

Epidemiology

Data in 1988 revealed that 30% to 40% of young patients who had a Cryptogenic stroke had a PFO. This percentage compared to 25% in the general population.[4] Since that time, the largest target population studied has been patients of all ages with cryptogenic stroke, in whom the frequency of finding a PFO is often double that of the general population. In adults with PFO, an optimal secondary prevention strategy is not well defined. Patients with PFO and atrial septal aneurysm who have experienced strokes seem to be at higher risk for recurrent stroke (as high as 15% per year), and secondary preventive strategies are necessary. In another study, 50% of patients with cryptogenic stroke were found to have right-to-left shunting compared to 15% of the controls. Approximately two-thirds of divers with undeserved (following safe dive profiles) decompression illness are found to have a PFO.[5]

Pathophysiology

PFO is a flap-like opening between the atrial septum secundum and primum at the fossa ovalis (see Image. Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO). In utero, it serves as a conduit for blood to the systemic circulation. Once the pulmonary circulation increases after birth, the functional PFO starts to close. Anatomical closure of the PFO usually occurs at about 12 months. PFO primarily increases the risk of stroke from a paradoxical embolism. The risk for a cryptogenic stroke in patients with PFO increases with the larger defects and the presence of interatrial aneurysm (perhaps because of increased in situ thrombus formation in the aneurysmal tissue or because PFOs associated with an interatrial septal aneurysm tend to be larger). Despite prior reports concerning paradoxical embolism through a PFO, this phenomenon's magnitude as a risk factor for stroke remains undefined because deep venous thrombosis is infrequently detected in such patients. In 1 study, pelvic vein thrombi were found more frequently in young patients with cryptogenic stroke than in those with a known cause of stroke. This finding may provide the source of venous thrombi, mainly when a source of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is not initially identified.[6]

History and Physical

The majority of patients with PFO are asymptomatic. However, some may present with severe clinical symptoms like migraines-like headaches, symptoms, and signs of ischemic brain stroke or a transient ischemic event to any of the vital organs ( brain, limb, kidneys, intestine, etc). Less common clinical presentations include paradoxical embolism, acute myocardial infarction, systemic embolism, and dyspnea at rest. The physical exam is usually unremarkable. A faint systolic murmur may be heard on auscultation due to turbulence of the flow across the foramen.

Evaluation

The most common circumstance prompting the search for PFO is a cryptogenic stroke ( Stroke with no identifiable contributor after extensive workup). PFO also represents a common incidental finding on routine echocardiograms performed for another reason, especially in the neonatal period. A PFO is usually detected by transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), or transcranial Doppler (see Video. Transesophageal Echocardiogram). TEE is the most sensitive test, mainly with contrast media injected during a cough or Valsalva maneuver. However, technical difficulties and the need for sedation make TEE less favorable in the neonatal and pediatric population. Evaluation for PFO in neonates with congenital heart disease should include a detailed description of the presence of PFO, size, flow restriction, and pressure gradient. Patients with cryptogenic strokes should also be evaluated for the existence of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Divers with more than 1 episode of undeserved decompression illness should undergo evaluation for a right to left shunt. A 2015 diving medicine consensus panel recommended contrasted provocative transthoracic echocardiography for this evaluation because it has a lower complication rate than TEE and is unlikely to miss a clinically significant PFO.[7] Patients with cryptogenic strokes should also be evaluated for venous thromboembolism (VTE) to assess the associated tendency for thromboembolism associated with PFO that influences morbidity and mortality.

Treatment / Management

PFO does not require treatment or follow-up in neonates and the pediatric population. PFO is vital in some congenital heart conditions dependent on blood shunting at the atrial level. In adults, treatment for PFO is mainly indicated in a patient with cryptogenic strokes. Different approaches have been suggested, including:

- Medical therapy mainly includes antithrombotic medications ( aspirin), especially in those with stroke due to embolism. Anticoagulant is indicated if the stroke is associated with vein thrombosis.

- Percutaneous device closure: Multiple studies and trials have shown the percutaneous device close of PFO is superior to medical therapy in reducing the risk for recurrence in patients less than 60 years old.[8] The FDA has approved the Cardioseal Septal occlusion system and the amp later PFO occluder for percutaneous closure. The procedure is done under fluoroscopic guidance and requires hospital admission. Aspirin or warfarin is required for a minimum of 6 months.

- A surgical approach to close PFO is pursued under the following conditions:

- PFO that is larger than 25 mm

- Failure of the PFO to close by percutaneous method

- The inadequate rim at the edge-this can make it difficult for percutaneous closure

The surgical approach results in complete closure and avoids needing long-term anticoagulants. However, surgery requires open-heart surgery and the usual procedure risks.

Differential Diagnosis

As mentioned earlier, PFO is a common finding in newborns and adults; the major differential diagnosis includes other congenital heart diseases like:

- Atrial septal defect ( In contrast with PFO, there is an actual defect in the septum, and usually fixed split-second heart sound is heard on examination)

- Ventricular septal defect ( Membrenous or muscular, usually associated with pansystolic murmur)

- Patent ductus arteriosus (another shunt that exists in fetal life as part of the fetal circulation may remain patent in newborns, and very few may stay patent into childhood. It is usually associated with continuous machinery murmur)

Prognosis

In neonates and children, the prognosis of PFO is excellent, and PFO usually closes in most of them. For those children and adults who require surgical closure due to thromboembolism risks, the prognosis is favorable. Surgical outcomes have been well established. Percutaneous closure is promising, but complications are not uncommon. Embolism, dislodgment, and failure to close the PFO have all been reported. Besides, the percutaneous procedure may be associated with damage to the blood vessels, stroke, thrombus formation, and infective endocarditis.

Complications

The usual complications of antiplatelet and anticoagulant therapies include bleeding and intracerebral hemorrhage. Intraprocedural complications utilizing device closure include perforation resulting in tamponade, air embolism, device embolization, and stroke. However, these are all rare events in experienced hands, with less than 1% rates. Subsequent atrial arrhythmias may occur in 3% to 5% but are transient. Although the rate of development of atrial fibrillation has been 5% to 6% with some devices, it is usually associated with thrombus formation. Late cardiac perforation has been reported with some devices but appears to be rare. In comparison, atrial fibrillation was more common among closure patients than anticoagulated patients in secondary preventive strategies.[9]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

PFO is a common finding in newborns. It is present in 25% of the general adult population and has been identified as the major contributing factor in cryptogenic stroke in 50% of affected young adults. Identifying PFO, particularly in young cryptogenic stroke patients, is accomplished via TEE with contrast media. Treatment aims to prevent a secondary event primarily with antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy or atrial septal device closure. The risk associated with either treatment is low overall, and the superiority of 1 therapy over the other is still contested. Accepted device closure treatment is for large PFOs and patients with PFOs who have already had a recurrent neurological event. Any identified venous thromboembolic event involving PFO should be treated with anticoagulation.[2]

The management of patent foramen ovale is made by an interprofessional team that consists of a pediatrician, cardiologist, interventional radiologist, and a cardiac surgeon. The decision to treat depends on the presence of symptoms, size, and presence of complications. Today, in high-risk patients, percutaneous methods of closure have evolved. Patients should be educated on their treatment options and possible complications of each treatment.

Media

(Click Video to Play)

Transesophageal Echocardiogram. Transesophageal echocardiogram, before and after patent foramen ovale closure, revealing delayed intracardiac shunting and hypoxemia after massive pulmonary embolism.

Weig T, Dolch M, Frey L, et al. Delayed intracardial shunting and hypoxemia after massive pulmonary embolism in a patient with a biventricular assist device. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;6:133.

doi: 10.1186/1749-8090-6-133.

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Patent Foramen Ovale. Most adult patients with patent foramen ovale are asymptomatic. In some adults, patent foramen ovale may result in an interatrial, right-to-left shunting of deoxygenated blood and the potential for shunting venous thromboembolism to the arterial circulation.

Contributed by O Chaigasame, MD

References

Connuck D, Sun JP, Super DM, Kirchner HL, Fradley LG, Harcar-Sevcik RA, Salvator A, Singer L, Mehta SK. Incidence of patent ductus arteriosus and patent foramen ovale in normal infants. The American journal of cardiology. 2002 Jan 15:89(2):244-7 [PubMed PMID: 11792356]

Pristipino C, Sievert H, D'Ascenzo F, Louis Mas J, Meier B, Scacciatella P, Hildick-Smith D, Gaita F, Toni D, Kyrle P, Thomson J, Derumeaux G, Onorato E, Sibbing D, Germonpré P, Berti S, Chessa M, Bedogni F, Dudek D, Hornung M, Zamorano J, Evidence Synthesis Team, Eapci Scientific Documents and Initiatives Committee, International Experts. European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. General approach and left circulation thromboembolism. European heart journal. 2019 Oct 7:40(38):3182-3195. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy649. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30358849]

Teshome MK, Najib K, Nwagbara CC, Akinseye OA, Ibebuogu UN. Patent Foramen Ovale: A Comprehensive Review. Current problems in cardiology. 2020 Feb:45(2):100392. doi: 10.1016/j.cpcardiol.2018.08.004. Epub 2018 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 30327131]

Meissner I, Whisnant JP, Khandheria BK, Spittell PC, O'Fallon WM, Pascoe RD, Enriquez-Sarano M, Seward JB, Covalt JL, Sicks JD, Wiebers DO. Prevalence of potential risk factors for stroke assessed by transesophageal echocardiography and carotid ultrasonography: the SPARC study. Stroke Prevention: Assessment of Risk in a Community. Mayo Clinic proceedings. 1999 Sep:74(9):862-9 [PubMed PMID: 10488786]

Kerut EK, Truax WD, Borreson TE, Van Meter KW, Given MB, Giles TD. Detection of right to left shunts in decompression sickness in divers. The American journal of cardiology. 1997 Feb 1:79(3):377-8 [PubMed PMID: 9036765]

Zoltowska DM, Thind G, Agrawal Y, Gupta V, Kalavakunta JK. May-Thurner Syndrome as a Rare Cause of Paradoxical Embolism in a Patient with Patent Foramen Ovale. Case reports in cardiology. 2018:2018():3625401. doi: 10.1155/2018/3625401. Epub 2018 Jul 2 [PubMed PMID: 30057826]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSmart D, Mitchell S, Wilmshurst P, Turner M, Banham N. Joint position statement on persistent foramen ovale (PFO) and diving. South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society (SPUMS) and the United Kingdom Sports Diving Medical Committee (UKSDMC). Diving and hyperbaric medicine. 2015 Jun:45(2):129-31 [PubMed PMID: 26165538]

. Correction: Device Closure Versus Medical Therapy Alone for Patent Foramen Ovale. Annals of internal medicine. 2018 Sep 18:169(6):428. doi: 10.7326/L18-0379. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30242419]

Giordano M, Gaio G, Santoro G, Palladino MT, Sarubbi B, Golino P, Russo MG. Patent foramen ovale with complex anatomy: Comparison of two different devices (Amplatzer Septal Occluder device and Amplatzer PFO Occluder device 30/35). International journal of cardiology. 2019 Mar 15:279():47-50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.10.053. Epub 2018 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 30344060]