Introduction

The concept of a regional anesthesia technique that provides neural blockade of the entirety of the lumbar plexus, a lumbar plexus block (LPB), dates back nearly 50 years. The first description of such a block by Winnie et al in 1973 was an “inguinal perivascular technique” alternatively referred to as a “3 in 1 technique”.[1] Winnie proposed that a large volume of local anesthetic injected in the femoral nerve sheath could spread proximally to produce blockade of the obturator, lateral femoral cutaneous, as well as femoral nerve (and presumably the other nerves of the lumbar plexus). Later work would show that, in fact, this rarely succeeded and typically only blocked the femoral and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves. In 1976 Chayen et al. described a “posterior lumbar plexus block” or “psoas compartment block,” which proved to be a more reliable realization of the goal of blocking the whole of the lumbar plexus with a single injection.[2] Touray et al. were among those who demonstrated that whereas both approaches effectively block femoral and lateral femoral cutaneous nerves, indeed, only the posterior lumbar plexus approach is also able to block the obturator nerve.[3] Thus today, the term “lumbar plexus block” is generally not associated with the inguinal femoral nerve block and is considered synonymous with the posterior approach.

Since the initial description of the posterior lumbar plexus block, a number of variations of the technique have been described. Most of these differ from the original technique of Chayen et al in only minor detail and are related to the distance of the needle insertion point from the midline or the lumbar level at which the block is performed.[4][5] Perhaps the most significant changes have been in defining the block’s endpoint. The original technique relied on a “loss of resistance,” but this transitioned to the more common use of a nerve stimulator technique (typically looking for motor stimulation of the femoral nerve with quadriceps twitch). More recently, the nerve stimulation method has given way to ultrasound-guided techniques of lumbar plexus block for which several approaches have been described. Thus far, the evidence is lacking to support the superiority of any one of the ultrasound-guided techniques.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The lumbar plexus (LP) is formed within the body of the psoas muscle by the four spinal nerves of L1 to L4. In 60% of people, the lumbar plexus receives a contribution from the nerve root of T12 as well.[6] Anatomical variations in the formation of the LP have been described with a prevalence of 20% to 40%.[7][8] Most common variants are related to the presence of an accessory obturator nerve or an isolated obturator nerve surrounded by a muscular fold, different nerve root derivation of the femoral cutaneous nerve, or a bifurcation of the femoral nerve within the psoas muscle. Whether or not these anatomical variations have clinical implications for the LP block is unknown.[8]

The psoas major muscle is composed of two portions, an anterior portion that arises from the anterolateral surface of the intervertebral discs and vertebral bodies, and a posterior portion that originates from the anterior aspect of the transverse processes. These two portions of the psoas are separated by a fascia creating in effect a “compartment” between them. It is in this fascial plane that the lumbar plexus is formed from its component nerve roots alongside the lumbar ascending vein and branches of the lumbar artery. This plane extends medially, opening into a wedge-shaped space at the medial surface of the psoas muscle, the lumbar paravertebral space.[9] The component nerve roots of the lumbar plexus each exit the neural canal through their respective intervertebral foramen, turn in a steep caudal direction across the lumbar paravertebral space, and access the psoas muscle one vertebral level below. Once formed in this fascial plane between the psoas muscle bodies, the component nerves of the lumbar plexus take their paths, each diving in a separate direction into the body of the psoas muscle from which they each exist separately.

The main branches of the lumbar plexus are considered below:

- Iliohypogastric nerve: Formed by T12 and L1, it travels across the psoas muscle and arises at the upper lateral border of this muscle between the anterior surface of quadratus lumborum and the posterior surface of the kidney.

- Ilioinguinal nerve: Formed by L1, arises from the lateral border of the psoas muscle just below the iliohypogastric nerve. It follows a downward trajectory on the anterior surface of the quadratus lumborum and upper part of the iliacus.

- Genitofemoral nerve: Formed mainly by L1-L2, arises from the anterior surface of the psoas muscle along the medial border. It follows a downward trajectory on the psoas muscle within the fascia iliaca and crosses posterior to the ureter and peritoneum. This nerve provides innervation to the cremaster muscle, skin of the femoral triangle, scrotum, pubis, and labium majus.

- Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve: Formed by the posterior division of L2 and L3 lumbar nerves. Arises beneath the lateral margin of the psoas muscle and follows downward laterally deep to the fascia over the iliacus muscle and finally crosses under the inguinal ligament medial to the anterior superior iliac spine. The lateral femoral cutaneous nerve provides sensory innervation to the skin of the anterolateral aspect of the thigh, and some of its terminal branches contribute to the patellar plexus.

- Femoral nerve: Formed by the posterior division of L2, L3, L4, within the psoas muscle, and exits from the lateral border of the psoas major in the fossa iliaca roughly 4 centimeters above the inguinal ligament. From here it enters the femoral triangle, laterally to the femoral sheath, and after a short distance divides into its terminal branches.

- The femoral nerve gives motor innervation to the quadriceps muscle and sensory innervation to the knee through the peripatellar plexus and the medial aspect of the leg through the saphenous nerve.

- Obturator nerve: Formed by the anterior division of L2, L3, L4, within the psoas muscle and follows a downward trajectory within the muscle body to arise on the medial side of the psoas at the level of the pelvic brim. Upon exiting the psoas, the nerve continues in a postero-lateral direction towards the sacroiliac joint. The obturator nerve provides motor innervation to adductor muscles in the medial aspect of the thigh and sensory innervation to the hip joint and knee joint.

As the lumbar plexus is formed from the component nerve roots, it acquires a triangular shape wider at its caudal portion while fanning out medial-laterally with the femoral nerve situated in the middle, the obturator nerve to the medial, and the lateral cutaneous nerve to the lateral. Magnetic resonance imaging studies have demonstrated that the spread of local anesthetic in a psoas block is usually within the psoas muscle, most of the time along the internal fascial plane with a cephalad spread to lumbar nerve roots and around the lumbar branches.[10] The terminology is confusing because the term “psoas sheath” block has been used to mean blocking the LP within the psoas whereas the term “psoas compartment” block has been used to mean injection external and posterior to the psoas between psoas and quadratus muscles rather than the compartment between muscle bodies of the psoas. It is believed, based on dye injection studies, that 20% to 40% of the time, a traditional lumbar plexus block is actually in this space rather than in the psoas.

Several studies have described the distance from the skin to the lumbar plexus specifically. In general, that distance ranges from 9 to 10 cm and is slightly deeper in males than in females.[6] The distance between the anterior border of the transverse process to lumbar plexus ranges between 1.5 to 2.0 cm, with a median value of 1.8 cm in both sexes. Caution is urged regarding the depth of needle insertion as insertion more than 2.0 to 3.0 cm beyond the transverse process may increase the risk of retroperitoneal or even intraperitoneal injury. Similarly, a needle insertion deeper than 10 to 12 cm may increase the risk of injury.[11]

Indications

The lumbar plexus block (LPB) is most commonly used to provide perioperative analgesia but may also be used as a surgical anesthetic, particularly when combined with a sciatic nerve block. The LPB is typically used to provide analgesia following injuries or surgeries of the hip or thigh (eg, acetabular fractures, femoral neck or mid-shaft fractures, hip replacement, hip arthroscopy, and knee replacement) but has also been used for chronic pain conditions such as Herpes zoster. It is important to note that the LPB is unlikely by itself to produce complete anesthesia for hip replacement surgery due to the innervation of the posteromedial hip capsule deriving from branches of the sacral plexus and sciatic nerve.[5]

Contraindications

The contraindications for lumbar plexus block are similar to other regional anesthesia techniques:

- Patient refusal

- Allergy to local anesthetics

- Local infection

- Systemic anticoagulation (INR >1.5 or inadequate time since cessation of anticoagulant)

Relative contraindications or where one might consider an alternative technique:

- Presence of intrathecal pump or spinal cord stimulator

- Major lumbar spine deformity

- Prior major spine surgery, implanted hardware, fusion

- Preexisting neurologic deficit

Equipment

Neurostimulation Technique

- Insulated stimulating needle (10 cm length; caution: 15 cm needle will only rarely be needed)

- Peripheral nerve block stimulator + surface electrode

- One 23 to 25-gauge needle for skin infiltration

- One 8 to 10 cm 25 gauge spinal needle

- 20 mL of local anesthetic

- 1 pack of gauze 4-inch x 4-inch

- Chlorhexidine gluconate solution for skin asepsis

- Sterile gloves

- Marking pen

Ultrasound-guided Technique

- Low frequency (5 to 10 Hz) curved transducer

- One 23 to 25-gauge needle for skin infiltration

- 20 mL of local anesthetic

- 1 pack of gauze 4-inch x 4-inch

- Chlorhexidine gluconate solution for skin asepsis

- Sterile gloves

- Marking pen

Personnel

The lumbar plexus block is a deep block, considered an advanced regional anesthesia technique that should only be performed by trained physicians. It is helpful to have the assistance of a nurse with training in regional anesthesia both to assist in the performance of the block and to help with administering sedation to the patient.

Preparation

A standard preoperative assessment should be conducted for any anesthesia procedure, including medical history, physical exam, airway assessment, and review of test results. Of special note are an allergic history, a history of neuropathy or demyelinating disease, coagulopathy, and a history of chronic pain. Current patient prescriptions, including analgesics and anticoagulants, should be noted. The patient should be informed about the benefits and risks of the lumbar plexus block, as well as describe what the procedure implies in the course of his informed consent. As with all nerve blocks, this procedure should be performed in a proper setting that has available monitoring, oxygen, suction, and resuscitation equipment.

Technique or Treatment

There are several variants of the landmark technique used together with neurostimulation to identify the femoral nerve within the psoas by evoking a motor response of the quadriceps muscle. While these techniques differ somewhat in terms of the needle insertion point (lumbar level, distance from midline), we will describe what we believe is the most common practice.

Standard American Society of Anesthesiologists monitoring is applied, and the patient is positioned in lateral decubitus on the side opposite the surgery, the side of the block upward. The ipsilateral knee flexed at 90º, and the hip flexed at 30º. The needle insertion point is marked 4 to 5 centimeters lateral to the midline at the level of the iliac crest along the intercristal line. The area of the block is then sterilely prepped and draped with sterile towels. A safety time-out is performed with the participation of the patient, nurse, and physician to confirm the patient's identity, the procedure, and the laterality. As the LP block may be uncomfortable for the patient, mild sedation is often given using small doses of intravenous midazolam and/or fentanyl. See Image. Lumbar Plexus Block Technique.

- Local anesthesia using lidocaine 1% is injected using the 23 to 25-gauge needle at the marked site of needle introduction along the same trajectory planned for the nerve block needle.

- The 25-gauge spinal needle is introduced at this site, perpendicular to the skin, attempting to locate the transverse process. If the transverse process is not found, the needle is withdrawn to a subcutaneous depth and reinserted with a slight caudad or cephalad angulation. This fanning exploration is repeated until the transverse process is located. Its depth and direction are noted, or it can be left in place with the nerve block needle to be inserted alongside it.

- The neurostimulator is set at a current of 1.5 mA with 0.1 msec pulse width duration at 2 Hz and attached to both the block needle and an electrocardiogram (EKG) pad on the skin. The block needle is inserted alongside or in place of the spinal finder needle, and at the depth determined by the finder needle, the transverse process is contacted.

- The block needle is now withdrawn and redirected either caudally or cephalad and to a depth 2 cm greater than that of contact with the transverse process. This may need to be repeated several times until a twitch response of the quadriceps muscle is elicited.

- Precise positioning of the needle is guided by decreasing the current delivery of the neurostimulator until a motor response is still visible at 0.5 mA.

- Inject the local anesthetic in fractionated aliquots, aspirating between each to be sure the needle is not intravascular.

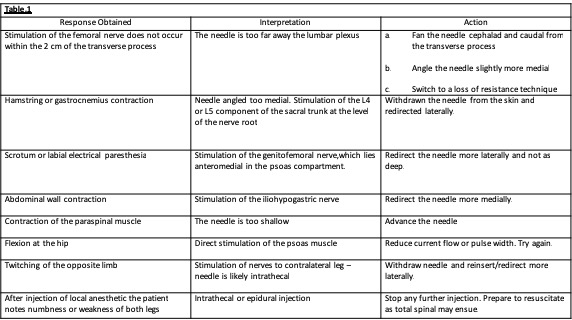

Although the technique described above seems to be straightforward, occasionally, all does not proceed as planned. Below are a number of tips for troubleshooting these situations.

There are some additional considerations when placing a continuous lumbar plexus catheter. While the technique of positioning the needle is the same as with a single shot lumbar plexus block, there is a small risk of catheter misplacement intravascular or neuraxial despite proper needle placement. Therefore, catheters should always be tested for negative aspiration for blood or cerebral spinal fluid, and injection of local anesthetic should be fractionated and slow. The final positioning of the catheter should be at a depth of the skin of 4 to 5 centimeters more than the depth of the needle at its final positioning. A continuous infusion of 8 to 10 mL/hr of ropivacaine 0.2% is enough to produce excellent analgesia. If weakness precludes participation in physical therapy, the infusion rate can be reduced. Alternatively, the infusion can be increased in the event of poorly controlled pain. The development of foot drop is not a sign of excessive block and should not be mistaken as being due to the block. It is likely a surgical complication (eg, hematoma, bone fragment, dislocation), causing sciatic compression and should be addressed urgently. The ultrasound-guided technique is beyond the scope of this review.

Complications

Complications related to the lumbar plexus block are infrequent. Although there are authors who report a high incidence of local anesthetic spread to the epidural space, our experience at the University of Pittsburgh is quite the opposite.[5][12] With the epidural spread, one would expect contralateral spread, bilateral weakness, hypotension, and difficulty with micturition. Indeed this is, in our experience, exceedingly rare. More medial needle insertion and a more cephalic approach (L3) may increase the likelihood of this complication.[5]

Intrathecal injection and spinal anesthesia as a complication of lumbar plexus block are also rare. Its prevalence is unknown as the vast majority of information comes from case reports and a few observational.[13][14][15] Auroy et al. cited 5 cases of major complications after the LP block from a sample of 394 patients.[16] This report is greatly at odds with the experience of the University of Pittsburgh, where the acute pain service has performed many thousands of LP blocks over the last two decades with few complications altogether, no case of direct intrathecal injection, and only one incident of intrathecal catheter placement.

A renal injury such as a subcapsular hematoma is another rare complication of LP block. This complication is associated with the use of a more cephalad injection site, such as at the level of L3. This is one reason that the intercristal line is used as it will lead to needle placement at the L4 or L5 transverse process. Additionally, caution on not advancing the needle more than 2 cm deep to the transverse process will help avoid this complication. Local anesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST) is a potential complication of any nerve block. Most commonly, this is a result of intravascular injection but can also result from the use of an excessive dose of local anesthetic. Treatment should include immediate administration of intravenous intralipid and supportive measures.

Retroperitoneal or psoas hematoma or other vascular injuries are major complications of LP block but are fortunately quite rare. The risk of bleeding in a non-compressible space such as the psoas compartment is uncertain but is of greater concern when the bleeding site can not be compressed and observed. Therefore patients on anticoagulation therapy or with a diagnosis of coagulopathy may not be proper candidates for this block. Deep plexus blocks such as this should follow the American Society of Regional Anesthesia (ASRA) guidelines of 2018 for neuraxial blocks in patients receiving anticoagulation or anti-aggregation therapy.[17]

The risk of a peripheral nerve injury is one of the most common questions patients ask their physicians. Fortunately, it is also a rare complication. The long-term peripheral nerve injury was found to have an incidence of 2 to 4 cases per 10.000 peripheral nerve blocks of all types.[18] Specifically, the rate of peripheral nerve injury reported for the lumbar plexus block may be as low as 0.1%.[19] A muscle twitch response during neurostimulation at a current of less than 0.2 mA is correlated with a high rate of histological nerve injury.[20] When nerve stimulation occurs at such a low current, the needle should be withdrawn a small distance so that 0.5 mA is needed to achieve muscle twitch.

Clinical Significance

The lumbar plexus block is considered an advanced regional anesthesia technique that, for many years, has proven efficacy. Concerns about safety, particularly in centers with a great deal of experience and where it is standard practice, seem much overblown. From the experience of the authors, the lumbar plexus block used as part of multimodal analgesia for lower limb surgery is a powerful and reliable tool for postoperative pain management. The lumbar plexus block decreases opioid consumption, enhances patient comfort, and promotes postoperative ambulation and physical therapy. It can play a pivotal role in enhanced recovery programs for hip surgery. Knowledge of the anatomy of the lumbar plexus, the different techniques of the block, its indications, and contraindications are considered essential for every practicing anesthesiologist and acute pain physician.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Acute pain management after surgery relies on an interprofessional responsibility, where the surgeon, the nurses, the physical therapist, and the anesthesiologist should work as a team to provide the best strategy for the patient's recovery. The Enhanced Recovery After Surgery defined multiple steps to achieve a faster and better recovery after surgery. The multimodal analgesia strategy for pain management includes the use of Peripheral nerve blocks to reduce opioid consumption, postoperative nausea and vomiting, and the exposure of naive patients to opioids that could end in misuse in up to 10% of the patients that never had opioids before. Additionally, this strategy includes the use of non-opioid medication for pain management like non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, ketamine, and lidocaine, as the first line of treatment for postoperative pain management, reserving the opioids for moderate to severe pain. The education of the surgical team on the importance of an adequate evaluation of pain, treatment, dosing, and strategies for pain control is fundamental for the recovery of the patient.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Winnie AP, Ramamurthy S, Durrani Z. The inguinal paravascular technic of lumbar plexus anesthesia: the "3-in-1 block". Anesthesia and analgesia. 1973 Nov-Dec:52(6):989-96 [PubMed PMID: 4796576]

Chayen D, Nathan H, Chayen M. The psoas compartment block. Anesthesiology. 1976 Jul:45(1):95-9 [PubMed PMID: 937760]

Touray ST, de Leeuw MA, Zuurmond WW, Perez RS. Psoas compartment block for lower extremity surgery: a meta-analysis. British journal of anaesthesia. 2008 Dec:101(6):750-60. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen298. Epub 2008 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 18945717]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAwad IT, Duggan EM. Posterior lumbar plexus block: anatomy, approaches, and techniques. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2005 Mar-Apr:30(2):143-9 [PubMed PMID: 15765457]

de Leeuw MA, Zuurmond WW, Perez RS. The psoas compartment block for hip surgery: the past, present, and future. Anesthesiology research and practice. 2011:2011():159541. doi: 10.1155/2011/159541. Epub 2011 May 22 [PubMed PMID: 21716721]

Farny J, Drolet P, Girard M. Anatomy of the posterior approach to the lumbar plexus block. Canadian journal of anaesthesia = Journal canadien d'anesthesie. 1994 Jun:41(6):480-5 [PubMed PMID: 8069987]

Sim IW, Webb T. Anatomy and anaesthesia of the lumbar somatic plexus. Anaesthesia and intensive care. 2004 Apr:32(2):178-87 [PubMed PMID: 15957714]

Anloague PA, Huijbregts P. Anatomical variations of the lumbar plexus: a descriptive anatomy study with proposed clinical implications. The Journal of manual & manipulative therapy. 2009:17(4):e107-14 [PubMed PMID: 20140146]

Gadsden J, Latmore M, Levine DM, Robinson A. High Opening Injection Pressure Is Associated With Needle-Nerve and Needle-Fascia Contact During Femoral Nerve Block. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2016 Jan-Feb:41(1):50-5. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000346. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26650431]

Mannion S, Barrett J, Kelly D, Murphy DB, Shorten GD. A description of the spread of injectate after psoas compartment block using magnetic resonance imaging. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2005 Nov-Dec:30(6):567-71 [PubMed PMID: 16326342]

Di Benedetto P, Pinto G, Arcioni R, De Blasi RA, Sorrentino L, Rossifragola I, Baciarello M, Capotondi C. Anatomy and imaging of lumbar plexus. Minerva anestesiologica. 2005 Sep:71(9):549-54 [PubMed PMID: 16166916]

Capdevila X,Coimbra C,Choquet O, Approaches to the lumbar plexus: success, risks, and outcome. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2005 Mar-Apr; [PubMed PMID: 15765458]

Pousman RM, Mansoor Z, Sciard D. Total spinal anesthetic after continuous posterior lumbar plexus block. Anesthesiology. 2003 May:98(5):1281-2 [PubMed PMID: 12717153]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDuarte LT, Saraiva RA. [Total spinal block after posterior lumbar plexus blockade: case report.]. Revista brasileira de anestesiologia. 2006 Oct:56(5):518-23 [PubMed PMID: 19468598]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDogan Z, Bakan M, Idin K, Esen A, Uslu FB, Ozturk E. Total spinal block after lumbar plexus block: a case report. Brazilian journal of anesthesiology (Elsevier). 2014 Mar-Apr:64(2):121-3. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2013.03.002. Epub 2013 Oct 11 [PubMed PMID: 24794455]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAuroy Y, Benhamou D, Bargues L, Ecoffey C, Falissard B, Mercier FJ, Bouaziz H, Samii K. Major complications of regional anesthesia in France: The SOS Regional Anesthesia Hotline Service. Anesthesiology. 2002 Nov:97(5):1274-80 [PubMed PMID: 12411815]

Narouze S, Benzon HT, Provenzano D, Buvanendran A, De Andres J, Deer T, Rauck R, Huntoon MA. Interventional Spine and Pain Procedures in Patients on Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications (Second Edition): Guidelines From the American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, the European Society of Regional Anaesthesia and Pain Therapy, the American Academy of Pain Medicine, the International Neuromodulation Society, the North American Neuromodulation Society, and the World Institute of Pain. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2018 Apr:43(3):225-262. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000700. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29278603]

Neal JM, Barrington MJ, Brull R, Hadzic A, Hebl JR, Horlocker TT, Huntoon MA, Kopp SL, Rathmell JP, Watson JC. The Second ASRA Practice Advisory on Neurologic Complications Associated With Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine: Executive Summary 2015. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2015 Sep-Oct:40(5):401-30. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000286. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26288034]

Brull R, McCartney CJ, Chan VW, El-Beheiry H. Neurological complications after regional anesthesia: contemporary estimates of risk. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2007 Apr:104(4):965-74 [PubMed PMID: 17377115]

Sondekoppam RV, Tsui BC. Factors Associated With Risk of Neurologic Complications After Peripheral Nerve Blocks: A Systematic Review. Anesthesia and analgesia. 2017 Feb:124(2):645-660. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000001804. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28067709]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence