Introduction

Acute sinusitis is an inflammation of the sinuses. Because sinus passages are contiguous with the nasal passages, rhinosinusitis is often a more appropriate term. Acute rhinosinusitis is a common diagnosis, accounting for approximately 30 million primary care visits and $11 billion in healthcare expenditure annually. It is also a common reason for antibiotic prescriptions in the United States and throughout the world. Due to recent guidelines and concerns for antibiotic resistance and the judicious use of antibiotics, it is essential to have clear treatment algorithms available for such a common diagnosis.[1][2]

Rhinosinusitis can be classified into the following groups (based more on consensus rather than empirical research) [3]:

- Acute - symptoms lasting less than 4 weeks

- Subacute - symptoms last between 4 and 12 weeks

- Chronic - symptoms lasting more than 12 weeks

- Recurrent - four episodes lasting less than 4 weeks with complete symptom resolution between episodes

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Viruses are the most common cause of acute rhinosinusitis. The viral rhinosinusitis (VRS) pathogens include rhinovirus, adenovirus, influenza virus, and parainfluenza virus. The most common causes of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) are Streptococcus pneumoniae (38%), Haemophilus influenzae (36%), and Moraxella catarrhalis (16%).[4] Although rare, fungal infections can also cause acute rhinosinusitis, though this is almost exclusively seen in the immunosuppressed (uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, HIV positive, oncology patients undergoing active treatment, and patients on immunosuppressants for an organ transplant or rheumatologic conditions). Typical species include Mucor, Rhizopus, Rhizomucor, and Aspergillus. It is very important to understand the difference between acute invasive fungal sinusitis (IFS) seen in these patients, and allergic fungal sinusitis (AFS) which presents in immunocompetent individuals as a mass-like lesion occupying a sinus cavity and often causes chronic symptoms. AFS will be discussed elsewhere and is beyond the scope of this article.

Epidemiology

Acute rhinosinusitis accounts for 1 in 5 antibiotic prescriptions for adults, making it the fifth most common reason for an antibiotic prescription. Approximately 6% to 7% of children with respiratory symptoms have acute rhinosinusitis. An estimated 16% of adults are diagnosed with ABRS annually. Given the clinical nature of this diagnosis, there is a possibility of overestimation.

An estimated 0.5 to 2.0% of viral rhinosinusitis (VRS) will develop into bacterial infections in adults and 5 to 10% in children.[1][2]

Pathophysiology

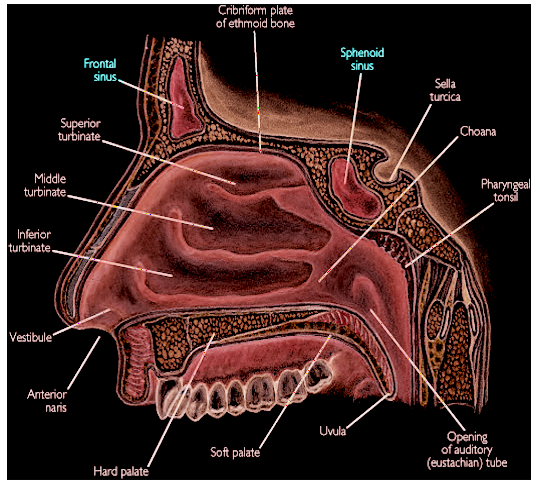

Sinuses function to filter out pollutants, microorganisms, dust, and other antigens. Sinuses drain into the intranasal meatus via small channels called ostia. The maxillary, frontal, and anterior ethmoid sinuses drain into the middle meatus, creating a congested area called the osteomeatal complex. The posterior ethmoid and sphenoid sinuses drain into the superior meatus. Tiny hairs called "cilia" line the mucous membranes of the nasal cavity and nasopharynx, and work in an integrated and coordinated fashion to carry out this function of circulating mucus and filtered debris, ultimately leading them to the nasopharynx and oropharynx, where they are swallowed. Rhinosinusitis occurs when the sinuses and nasal passages cannot effectively clear out these antigens, leading to an inflammatory state. This condition usually results from three key factors: obstruction of the sinus ostia (i.e., anatomic causes such as a tumor or septal deviation), dysfunction of the cilia (i.e., Kartagener syndrome), or thickening of sinus secretions (cystic fibrosis). The most common cause of temporary obstruction of these outflow regions is local edema due to upper respiratory tract infections (URI) or nasal allergy, both of which predispose to rhinosinusitis. When this occurs, bacteria can remain in, gain access to, and proliferate within the usually sterile paranasal sinuses. Severe complications can occur when the sinus infection spreads to surrounding structures, such as the brain and orbit, via the valve-less diploic veins. These are veins located within the inner cancellous bone layer of the skull. This is thankfully a rare phenomenon, but important to remember.

Adults have four developed and paired sinus cavities. The ethmoid, sphenoid, frontal, and maxillary sinuses. In children, only the ethmoid and maxillary sinuses are present at birth. The ethmoid sinus separates from the orbit by only a thin layer of bone (the lamina papyrecia). Thus, orbital infections typically arise from the ethmoid sinus, which occurs more often in younger children. The frontal sinuses do not appear to develop until 5 to 6 years of age and do not reach full development until after puberty. Intracranial complications typically arise from the frontal sinuses and thus occur more often in older children or adults. The sphenoid sinus starts to pneumatize at 5 years of age but does not fully develop until 20 to 30 years of age.

Histopathology

Healthy sinuses are composed of ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium, which uses cilia to clear the sinuses of debris, mucus, and other substances. The mucosal edema, infiltration of granulocytes and lymphocytes, squamous metaplasia, and fibroblast proliferation from acute rhinosinusitis disrupts this process.[5]

History and Physical

Acute rhinosinusitis is a clinical diagnosis. Three “cardinal” symptoms that are most sensitive and specific for acute rhinosinusitis are purulent nasal drainage accompanied by either nasal obstruction or facial pain/pressure/fullness. This must be elucidated specifically from patients who will present with generic "headache" complaints. Isolated headache is not a symptom of sinusitis (with the rare exception of sphenoid sinusitis, which can present as an occipital or vertex headache and is usually chronic), but facial pressure is. The astute clinician must elicit this history from the patient to determine the exact symptoms they are experiencing.

When cardinal symptoms persist beyond ten days or if they worsen after an initial period of improvement (“double worsening”), one may diagnose ABRS. Other symptoms associated with acute rhinosinusitis include cough, fatigue, hyposmia, anosmia, maxillary dental pain, and ear fullness or pressure. Anterior rhinoscopy may reveal mucopus emanating from the osteomeatal complex, or this may be demonstrated on formal endoscopic rhinoscopy in the clinic.[3]

Children have a slight variance in the clinical presentation of ABRS. In addition to the 10-day duration, cardinal symptoms, and “double worsening,” children are more likely to present with fevers. Nasal discharge may initially be watery, then turn purulent. A viral upper respiratory infection precedes approximately 80% of acute bacterial sinusitis.[6]

Severe symptoms are more indicative of a bacterial cause. These include high fevers (over 39 C or 102 F) accompanied by purulent nasal discharge or facial pain for three to four consecutive days at the beginning of the illness. Viral illnesses typically resolve after three to five days.

Antibiotic resistance factors should also merit consideration. These include [4]:

- Antibiotic use within the last month

- Hospitalization within the previous five days

- Healthcare occupation.

- Local patterns of antibiotic resistance known to healthcare organizations in the community

Lastly, one should assess whether a patient is at higher risk. These characteristics include [3]:

- Comorbidities (i.e., cardiac, renal, or hepatic disease)

- Immunocompromised states

- Age under 2 years or over 65 years

Fungal acute rhinosinusitis is most commonly associated with fevers, nasal obstruction or bleeding, and facial pain in an immunocompromized patient, though it can also be asymptomatic. Refractory or severe symptoms in an immunocompromised patient should prompt consideration of this diagnosis.

Evaluation

Acute rhinosinusitis is a clinical diagnosis. The clinician most commonly needs to distinguish between VRS and ABRS, which is crucial to ensure the responsible usage of antibiotics. Local resistance patterns and prevalence of penicillin non-susceptible S. pneumoniae requires elucidation.

Conventional diagnostic criteria for rhinosinusitis in adults is the patient having at least two major or one major plus two or more minor symptoms. The criteria in children are similar except that there is more of an emphasis on nasal discharge (rather than nasal obstruction).Major symptoms:

- Purulent anterior nasal discharge

- Purulent or discolored posterior nasal discharge

- Nasal congestion or obstruction

- Facial congestion or fullness

- Facial pain or pressure

- Hyposmia or anosmia

- Fever (for acute sinusitis only)

Minor symptoms:

- Headache

- Ear pain or pressure or fullness

- Halitosis

- Dental pain

- Cough

- Fever (for subacute or chronic sinusitis)

- Fatigue

ABRS can be differentiated from VRS using the following clinical guidance[4][6][1][3]:

- Duration of symptoms for more than ten days

- High fever (over 39 C or 102 F) with purulent nasal discharge or facial pain that last for 3 to 4 consecutive days at the beginning of the illness

- Double worsening of symptoms within the first ten days

Routine laboratory assessment is generally not necessary. Evaluation for cystic fibrosis, ciliary dysfunction, or immunodeficiency are considerations for intractable, recurrent, or chronic rhinosinusitis. There is some evidence that an elevated ESR and CRP may be associated with a bacterial infection.

The culture of endoscopic aspirates with greater than or equal to 10 CFU/mL is considered the gold standard. However, this is not necessary for diagnosis and not done for the vast majority of cases of ABRS. Nasal and nasopharyngeal cultures are of low utility due to their poor correlation with endoscopic aspirates. Referral for endoscopic aspiration can be useful for refractory cases or patients with multiple antibiotic allergies.

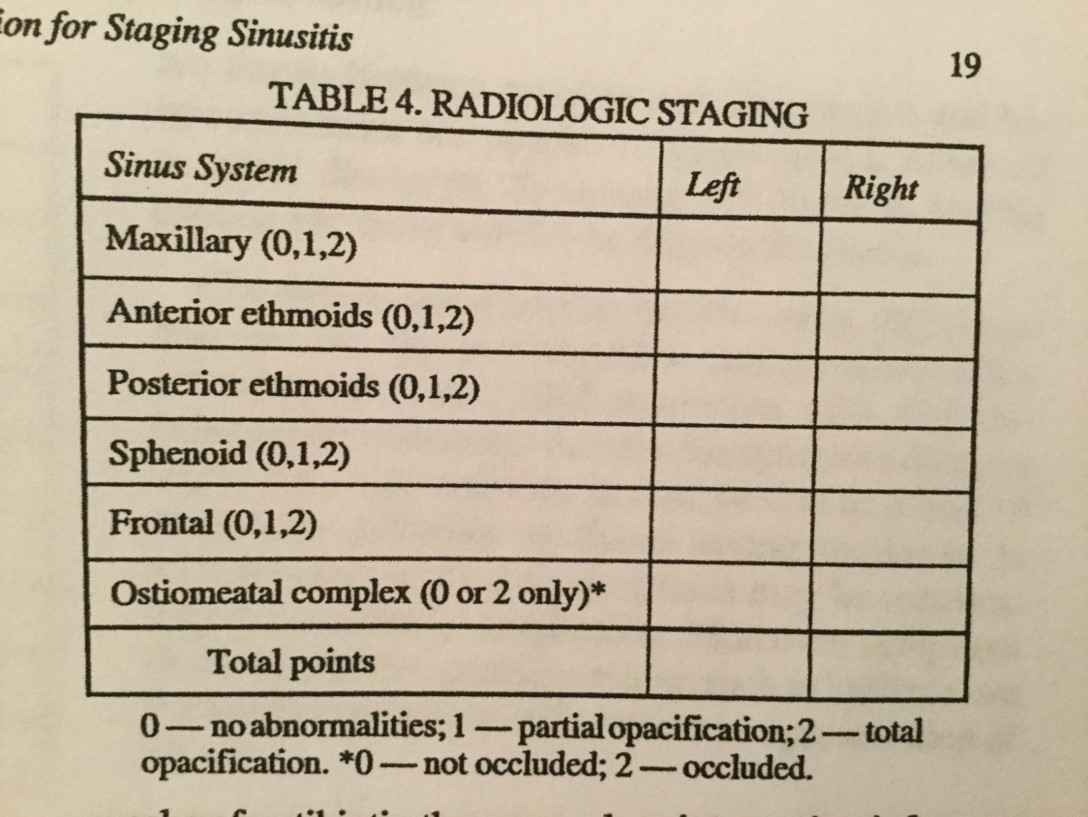

Imaging for acute sinusitis is not necessary unless there is a clinical concern for a complication or alternative diagnosis. Sinus plain films are generally not useful in detecting inflammation. They may show air-fluid levels. However, this does not help differentiate viral versus bacterial etiologies. If a complication or alternative diagnosis is suspected, or if the patient has recurrent acute infections, then sinus CT imaging should be obtained to assess for bone, soft tissue, dental, or other anatomical abnormalities or the presence of chronic sinusitis. These should be obtained at the end of an appropriate treatment course. Sinus CT may show air-fluid levels, opacification, and inflammation. A thickened sinus mucosa over 5 mm is indicative of inflammation. It can also effectively assess bony erosion or destruction. However, these findings are also not helpful in differentiating viral versus bacterial etiologies. MRI offers more detail than sinus CT to evaluate soft tissue or help elucidate a tumor. Thus, MRI may be helpful to determine the extent of complications in cases such as an orbital or intracranial extension.

Treatment / Management

Treatment of ABRS consists of either antibiotic therapy or a period of watchful waiting so long as the certainty of reliable follow-up. There are slight variations between different expert committee guidelines.[7]

The American Academy of Otolaryngology Adult Sinusitis 2015 updated guideline recommends amoxicillin with or without clavulanate in adults as first-line therapy for a period of 5 to 10 days in most adults. Treatment failure is noted if symptoms do not decrease within 7 days or worsen at any time.

The Infectious Disease Society of America Guidelines for Acute Bacterial Rhinosinusitis recommends amoxicillin with clavulanate in adults as first-line therapy for 10 to 14 days in children and 5 to 7 days in adults. Treatment failure is noted if symptoms do not decrease after 3 to 5 days or worsen after 48 to 72 hours of therapy.

The American Academy of Pediatrics Clinic Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children Aged to 18 Years recommends amoxicillin with or without clavulanate as first-line therapy. The duration of treatment is unclear, however treating for an additional seven days after symptoms resolve was their suggestion. The criteria for treatment failure is if symptoms do not decrease or worsen after 72 hours of therapy. If the patient cannot tolerate oral fluids, then the patient can receive ceftriaxone 50m/kg. If the patient can tolerate oral fluids the next day and improves, then the patient can transition to an oral antibiotic course thereafter. A separate article recommended amoxicillin with clavulanate as initial therapy in children to adequately cover beta-lactamase-producing pathogens.[8]

Local antibiotic resistance patterns, the patient's risk level, risk factors for antibiotic resistance, and severity of symptoms help determine whether to add clavulanate or whether high-dose amoxicillin (90mg/kg/day versus 45mg/kg/day) should be used in children.

For patients allergic to penicillin, a third-generation cephalosporin plus clindamycin (for adequate coverage of non-susceptible S. pneumoniae) or doxycycline could be therapeutic possibilities. Third-generation cephalosporins alone have variable efficacy rates against S. pneumoniae. Fluoroquinolones could also be considered but are associated with a higher rate of adverse events. Doxycycline and fluoroquinolones should be used with more caution in children. There are higher rates of S. pneumoniae and Hemophilus influenzae resistance to second-generation cephalosporins, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and macrolides.

Evidence has also shown that antibiotic therapy does not necessarily shorten symptom duration or complication rates in adults. Many cases of ABRS may also spontaneously resolve within two weeks.[9]

Clinicians can offer symptomatic treatments; however, clear evidence is lacking overall. Nasal steroids and nasal saline irrigation are the most common recommendations in guidelines. Intranasal steroids may help by reducing mucosal swelling, which can help relieve the obstruction. A small number of trials indicated that higher doses of intranasal steroids could help improve the time to symptom resolution at 2 to 3 weeks.[10] Nasal saline irrigation can also help reduce obstruction. Antihistamines are not a recommendation unless there is a clear allergic component as they potentially thicken nasal secretions.(A1)

Suspicion for the invasive form of acute fungal rhinosinusitis should prompt urgent evaluation and referral to otolaryngology, neurosurgery, and/or ophthalmology for biopsy. These patients will require combined medical and surgical management (debridement) if this diagnosis is confirmed on histology.[11]

Differential Diagnosis

It is most important to differentiate between acute viral versus bacterial rhinosinusitis. Allergic rhinitis is also a common condition requiring elucidation. Fungal infections may also cause rhinosinusitis. Invasive fungal sinusitis is a serious form of this infection that is more common in immunocompromised patients. It is associated with a high mortality rate. Other less common diagnoses to consider in the differential diagnosis include:

- Nasal foreign body

- Enlarged or infected adenoids

- Structural abnormalities, i.e., deviated septum, sinonasal neoplasm

- Disorders affecting ciliary function, i.e., primary ciliary dyskinesia, cystic fibrosis

- Referred pain, i.e., dental infection or abscess

- Upper respiratory infection

Prognosis

Acute bacterial rhinosinusitis is most commonly viral. The large majority of cases will either resolve spontaneously or can be effectively treated with antibiotics. Invasive fungal rhinosinusitis is a rare, serious form of the infection that can occur in immunocompromised patients. It is associated with a high morbidity and mortality rate. [11]

Complications

Complications are rare, occurring in about 1 out of every 1000 cases.[1] Sinus infections may spread to the orbit, bone, or intracranial cavities. Eighty percent of orbitocranial complications occur in the orbit. These complications can come with significant morbidity and mortality. The orbit is the most common site due to the very thin ethmoid bone that separates infections from the ethmoid to the orbit. The Chandler classification is the most common method or grading orbital complications of sinusitis infection (listed from least to most severe)[12]:

- Preseptal cellulitis

- Orbital cellulitis

- Subperiosteal abscess

- Orbital abscess

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis

Intracranial complications can also occur. These include the development of a subdural hematoma, epidural hematoma, meningitis, or a subdural empyema (the latter comes with a high mortality rate). Pott puffy tumor is a subperiosteal abscess of the frontal bone, usually associated with osteomyelitis. Both complications typically arise from frontal sinus infections, via hematogenous spread through the valveless diploic vein system.

Acute fungal sinusitis can occur in a noninvasive and invasive form.[13] The invasive form can spread to surrounding structures. Early identification of this complication is vital to avoiding potentially devastating outcomes.[11]

Consultations

Referral to an otolaryngologist is rarely needed since most cases are viral and will resolve spontaneously. Acute uncomplicated bacterial sinusitis can be easily treated by primary care physicians with antibiotics. However, if a complication is suspected, prompt referral to an otolaryngologist is required to avoid the potentially catastrophic effects of intracranial and orbital extension. Reasons for urgent referral include:

- Mental status changes

- Cranial nerve abnormalities

- Pain with extraocular movements

- Periorbital edema

- Severe or refractory symptoms in an immunocompromised patient

Routine referral to an otolaryngologist may also be done for any intractable or refractory case of rhinosinusitis to provide further evaluation.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Most causes of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis are viral. Most cases will resolve spontaneously. There is evidence that acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS) can also resolve spontaneously. The diagnosis of ABRS is clinical.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Acute rhinosinusitis is among the most common primary care conditions. To avoid high morbidity, an interprofessional team should manage the disorder. The critical thing of which clinicians need to be aware is that most cases result from viruses and are self-limiting. As such, it is crucial to be able to identify the three cardinal symptoms for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis. Clinicians should only prescribe antibiotics for the patient who exhibits prolonged symptoms without improvement for 10 days, “double-worsening,” or those with severe symptoms. Amoxicillin with or without clavulanate should be first-line therapy. Local antibiotic resistance factors, risk factors for antibiotic resistance, and the overall risk level of the patient should be a consideration. An infectious disease certified pharmacist can be a valuable resource, as they will often have the latest antibiogram data, can suggest antimicrobial alternatives if necessary, and check for drug interactions.

Imaging is not helpful except in cases where there a complication or alternative diagnosis is suspected. If complications are suspected, then urgent imaging and referral to otolaryngology, ophthalmology, and/or neurosurgery should be done to avoid potentially catastrophic outcomes. The nurse and the pharmacist should educate the patient on avoidance of smoking and getting the flu vaccine annually, as this may lower the risk of viral rhinosinusitis. Finally, the patient should understand that routine use of antibiotics is not necessary, as most cases resolve spontaneously; this is another area where nursing staff can guide the patient and answer any questions. However, referral to otolaryngology for a culture of endoscopic aspirates merits consideration for refractory cases. Open communication between interprofessional team members will inevitably lead to improved outcomes. [Level V]

"The opinions and assertions contained herein are the private views of the authors and are not to be construed as official or as reflecting the views of the Department of the Army, Department of the Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. government."

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Aring AM, Chan MM. Current Concepts in Adult Acute Rhinosinusitis. American family physician. 2016 Jul 15:94(2):97-105 [PubMed PMID: 27419326]

DeMuri G, Wald ER. Acute bacterial sinusitis in children. Pediatrics in review. 2013 Oct:34(10):429-37; quiz 437. doi: 10.1542/pir.34-10-429. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24085791]

Rosenfeld RM, Piccirillo JF, Chandrasekhar SS, Brook I, Ashok Kumar K, Kramper M, Orlandi RR, Palmer JN, Patel ZM, Peters A, Walsh SA, Corrigan MD. Clinical practice guideline (update): adult sinusitis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2015 Apr:152(2 Suppl):S1-S39. doi: 10.1177/0194599815572097. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25832968]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceChow AW, Benninger MS, Brook I, Brozek JL, Goldstein EJ, Hicks LA, Pankey GA, Seleznick M, Volturo G, Wald ER, File TM Jr, Infectious Diseases Society of America. IDSA clinical practice guideline for acute bacterial rhinosinusitis in children and adults. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2012 Apr:54(8):e72-e112. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir1043. Epub 2012 Mar 20 [PubMed PMID: 22438350]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBerger G, Kattan A, Bernheim J, Ophir D, Finkelstein Y. Acute sinusitis: a histopathological and immunohistochemical study. The Laryngoscope. 2000 Dec:110(12):2089-94 [PubMed PMID: 11129027]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWald ER, Applegate KE, Bordley C, Darrow DH, Glode MP, Marcy SM, Nelson CE, Rosenfeld RM, Shaikh N, Smith MJ, Williams PV, Weinberg ST, American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of acute bacterial sinusitis in children aged 1 to 18 years. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul:132(1):e262-80 [PubMed PMID: 23796742]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceRosenfeld RM. CLINICAL PRACTICE. Acute Sinusitis in Adults. The New England journal of medicine. 2016 Sep 8:375(10):962-70. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1601749. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27602668]

Brook I. Acute sinusitis in children. Pediatric clinics of North America. 2013 Apr:60(2):409-24. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2012.12.002. Epub 2013 Jan 20 [PubMed PMID: 23481108]

Boisselle C, Rowland K. PURLs: Rethinking antibiotics for sinusitis: again. The Journal of family practice. 2012 Oct:61(10):610-2 [PubMed PMID: 23106063]

Zalmanovici Trestioreanu A, Yaphe J. Intranasal steroids for acute sinusitis. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Dec 2:2013(12):CD005149. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005149.pub4. Epub 2013 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 24293353]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDwyhalo KM, Donald C, Mendez A, Hoxworth J. Managing acute invasive fungal sinusitis. JAAPA : official journal of the American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2016 Jan:29(1):48-53. doi: 10.1097/01.JAA.0000473374.55372.8f. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26704655]

Knipping S, Hirt J, Hirt R. [Management of Orbital Complications]. Laryngo- rhino- otologie. 2015 Dec:94(12):819-26. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1547285. Epub 2015 Aug 26 [PubMed PMID: 26308141]

Schubert MS. Allergic fungal sinusitis: pathophysiology, diagnosis and management. Medical mycology. 2009:47 Suppl 1():S324-30. doi: 10.1080/13693780802314809. Epub 2009 Mar 27 [PubMed PMID: 19330659]