Introduction

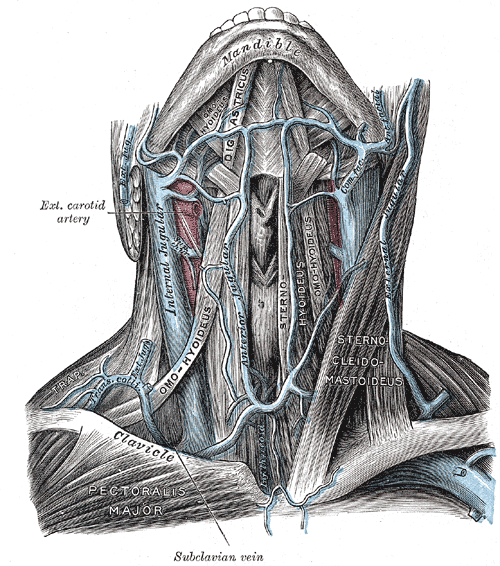

The external jugular vein, located in the anterior and lateral neck, receives blood from the deeper parts of the face as well as the scalp — the external jugular vein forms from the combination of the posterior auricular and retromandibular vein. The external jugular vein starts in the parotid at the level of the angle of the mandible and runs vertically down the neck along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle. At its distal end, the external jugular vein perforates the deep neck fascia and terminates in the subclavian vein. Throughout its course in the neck, the vein is immediately deep to the platysma muscle. During its course from the mandible, it runs parallel with the greater auricular nerve. Like most veins, the external jugular vein also has valves at the terminal end before it enters the subclavian vein. In patients with obstruction or occlusion of the subclavian vein, the external jugular may appear dilated. The vein is not always easily visible on external examination, particularly in obese patients. The size of the external jugular vein does vary with body habitus and size of the neck. In rare cases, there may be two small external jugular veins. The is some variation in course as it descends into the neck, but its path is more consistent than the anterior jugular. Awareness of its location is essential during head and neck surgery, where injury should be avoided (it can also be harvested as a vein graft). The vein can be cannulated to provide fluids and medications during resuscitation when more peripheral access cannot be easily established.[1]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The external jugular vein derives from the union of the posterior auricular vein and the posterior division of the retromandibular vein, which occurs in the substance of the parotid gland at the level of the angle of the mandible. It also may receive blood from the transverse cervical vein, the suprascapular vein, the superficial cervical vein, and the anterior jugular vein in some instances. The retromandibular vein anterior division joins with the facial vein to form the common facial vein. The anterior jugular vein is a related vein that is formed from submandibular veins and can drain into the external jugular vein or the subclavian vein directly, with the latter being more common.[2] The external jugular vein most commonly drains into the subclavian vein near the middle third of the clavicle. Like most veins, the external jugular vein has a valve at the terminal end before entering the subclavian vein. The function of this valve is to inhibit the regurgitation of blood from the subclavian vein into the external jugular vein, which is under relatively lower pressure. The function of the external jugular vein is to drain blood from the superficial structures of the cranium and the deep portions of the face.

Embryology

Before the eighth week of gestation, the left and right cardinal veins develop in the neck. At the eighth week of gestation, these cardinal veins form a large anastomosis, which will eventually form into the left brachiocephalic venous trunk. The left and right cardinal veins subsequently develop into the internal jugular veins. Around this same period of gestation, the external jugular veins form from the anterior veins of the mandibular region.

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

While there is no specific association of lymph nodes with the external jugular vein, the posterior lateral superficial cervical nodes lie in close proximity to the external jugular vein and the peri-facial lymph nodes may abut the retromandibular vein in some patients. Additionally, the thoracic duct drains into the subclavian vein near the junction of the external jugular, internal jugular, and the subclavian vein, classically inserting immediately lateral to the junction of the internal jugular and subclavian. Further discussion of the thoracic duct and its anatomical variants can be found in StatPearls under this topic. The thoracic duct primarily drains lymphatic fluid from the left half of the body above the diaphragm as well as the entire body below the diaphragm.[3]

Nerves

The superior portion of the external jugular vein runs parallel with the great auricular nerve. The great auricular nerve is a branch of the cervical plexus and provides sensory innervation to the auricle as well as the skin over the parotid gland and mastoid process. Clinically, a nerve block can be performed to the greater auricular nerve to provide anesthesia to a portion of the ear. Care must be taken to avoid injecting anesthetic into the external jugular vein during this procedure.[4]

Muscles

The external jugular vein courses superficial to and obliquely across the sternocleidomastoid muscle in the superficial fascia. Part of its descent in the neck is also along the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle in its lower third. It then descends superficial and anterior to the anterior scalene muscle before penetrating the investing deep cervical fascia and entering the subclavian vein. The platysma muscle lies superficial to it along its entire course.

Physiologic Variants

There are many structural variants of the external jugular vein, mostly without clinical significance. They are important to be cognizant of for head and neck surgeons operating near the external jugular vein. A documented variant of the origin of the external jugular vein shows the vein forming from the union of retromandibular veins, the anterior jugular vein, and the facial vein.[5] There can be significant variation in the connections along the external jugular vein. It is well-described for the facial vein to drain directly into the external jugular vein anywhere along its course. The facial vein typically drains into the internal jugular vein, though it can also empty into the anterior jugular vein quite frequently. It has been postulated that this anastomotic pattern is related to the persistence of the primitive linguofacial vein.[6] There have also been documented cases of anastomosis between the external jugular vein and internal jugular vein, with normal venous function.[7] There is a case of a persistent jugulocephalic vein with connection superficial to the clavicle. This vein had valves only allowing blood flow from the cephalic vein into the external jugular vein.[8] The external jugular vein can be absent or duplicated ipsilaterally or bilaterally. The duplication does not necessarily need to be the entire length of the vein. Duplication has been observed while exiting the parotid gland or in other sections of the vein.[2][1][9][10]

A related vein is called the vein of Kocher, or the posterior external jugular vein. It originates in the occipital region and is a tributary of the common facial vein. It travels anterior to the sternocleidomastoid muscle, in a similar fashion to the external jugular vein and can be larger than the external jugular vein in some instances. It is important to be aware of this variant for surgical purposes.[2]

Surgical Considerations

The external jugular vein is frequently utilized in head and neck microvascular surgery as both a recipient vessel for free tissue transfer and as a source of vein grafts. It is essential to understand the anatomy of this vein during dissection, even in non-microvascular operations, to avoid excessive intra-operative bleeding given its superficial location to many important structures. Understanding the structural variants of the external jugular vein is also important for head and neck surgeons.[5] The external jugular vein is an alternative site for implantation of a totally implantable venous access device (TIVAD).[11]

Additionally, given its superficial location, the external jugular vein can be damaged in penetrating trauma, leading to impressive bleeding. The management is often uncomplicated as the vein can undergo ligation without neurologic significance.

Clinical Significance

The external jugular vein is frequently used to obtain vascular access to administer medications or IV fluids in patients with problematic peripheral access, such as those on dialysis or in the intensive care unit who have had multiple prior peripheral IV catheters placed. The external jugular vein is not the first choice for venous cannulation as it is tortuous and can be challenging to cannulate in people with thick, short necks, and is more bothersome to patients than other peripheral IV locations. Unlike the internal jugular vein, the risk of complications from cannulation of the external jugular vein is much less and similar to any other peripheral site. The external jugular vein is ideally only used for short periods of hydration, as the dislodgement of the cannula is common due to the motion of the neck. The patient should be asked not to rotate the neck while the external jugular vein is in use. Because of its variable course and valves, the external jugular vein cannot be reliably used to assess jugular venous pressure.

To access the external jugular vein, the patient is first placed in Trendelenburg position to facilitate filling of the vein. Since a tourniquet cannot be applied, the patient can be asked to perform the Valsalva maneuver, or direct pressure can be applied just superior to the middle portion of the clavicle. Standard infection control practices are utilized by cleansing the skin with a chlorhexidine wipe and wearing gloves throughout the procedure. Needle insertion should be at a shallow angle (30 degrees or less) to the skin with the tip of the needle pointing obliquely from the midline along the course of the external jugular vein. Gentle manual traction can be applied to the skin overlying or just adjacent to a more distal portion of the vein to stabilize the vein for cannulation. Once you have achieved a flash of blood in the needle, the plastic catheter can be advanced into the vessel and secured. A challenge with external jugular vein cannulation is that there may not be an appreciable flash of blood into your needle, or it may occur more slowly than in other peripheral veins due to the lower pressure in the external jugular vein. One technique that can assist the practitioner is to attach a small syringe to the needle and hold gentle negative pressure on the syringe while advancing the needle; this will allow you to see blood return into the syringe and confirm entry into the external jugular vein.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Shenoy V, Saraswathi P, Raghunath G, Karthik JS. Double external jugular vein and other rare venous variations of the head and neck. Singapore medical journal. 2012 Dec:53(12):e251-3 [PubMed PMID: 23268166]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDalip D, Iwanaga J, Loukas M, Oskouian RJ, Tubbs RS. Review of the Variations of the Superficial Veins of the Neck. Cureus. 2018 Jun 18:10(6):e2826. doi: 10.7759/cureus.2826. Epub 2018 Jun 18 [PubMed PMID: 30131919]

Rivard AB, Kortz MW, Burns B. Anatomy, Head and Neck: Internal Jugular Vein. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30020630]

Chang KV, Wu WT, Özçakar L. Greater Auricular Nerve Entrapment/Block in a Patient With Postinfectious Stiff Neck: Imaging and Guidance With Ultrasound. Pain practice : the official journal of World Institute of Pain. 2020 Mar:20(3):336-337. doi: 10.1111/papr.12849. Epub 2020 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 31643126]

Chauhan NK, Rani A, Chopra J, Rani A, Srivastava AK, Kumar V. Anomalous formation of external jugular vein and its clinical implication. National journal of maxillofacial surgery. 2011 Jan:2(1):51-3. doi: 10.4103/0975-5950.85854. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22442610]

Choudhry R, Tuli A, Choudhry S. Facial vein terminating in the external jugular vein. An embryologic interpretation. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 1997:19(2):73-7 [PubMed PMID: 9210239]

Karapantzos I, Zarogoulidis P, Charalampidis C, Karapantzou C, Kioumis I, Tsakiridis K, Mpakas A, Sachpekidis N, Organtzis J, Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis K, Pitsiou G, Zissimopoulos A, Kosmidis C, Fouka E, Demetriou T. A rare case of anastomosis between the external and internal jugular veins. International medical case reports journal. 2016:9():73-5. doi: 10.2147/IMCRJ.S98801. Epub 2016 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 27051321]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWysiadecki G, Polguj M, Topol M. Persistent jugulocephalic vein: case report including commentaries on distribution of valves, blood flow direction and embryology. Folia morphologica. 2016:75(2):271-274. doi: 10.5603/FM.a2015.0084. Epub 2015 Sep 18 [PubMed PMID: 26383511]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParaskevas G, Natsis K, Ioannidis O, Kitsoulis P, Anastasopoulos N, Spyridakis I. Multiple variations of the superficial jugular veins: case report and clinical relevance. Acta medica (Hradec Kralove). 2014:57(1):34-7 [PubMed PMID: 25006662]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePonnambalam SB, Karuppiah DS. Unilateral external jugular vein fenestration with variant anatomy of the retromandibular and facial vein. Anatomy & cell biology. 2020 Mar:53(1):117-120. doi: 10.5115/acb.19.172. Epub 2020 Mar 3 [PubMed PMID: 32274258]

Iorio O, Cavallaro G. External jugular vein approach for TIVAD implantation: first choice or only an alternative? A review of the literature. The journal of vascular access. 2015 Jan-Feb:16(1):1-4. doi: 10.5301/jva.5000287. Epub 2014 Sep 2 [PubMed PMID: 25198827]