Introduction

The intimate connection between the nervous system and the lymphatic system in both health and disease has long been acknowledged in osteopathic medicine. In fact, treatments such as rib raising and occipital inhibition have as their foundation this very principle.[1] Though first described as neuro-lymphatic points by Frank Chapman, DO in the early 1900s, Chapman's points are now defined as organ-specific gangliform contractions associated with underlying visceral dysfunction.[2][3] More specifically, Chapman's points present as smooth and discreetly palpable nodules located deep within the fascia in regions related by dermatome to the dysfunctional viscera. These points are sharp, pinpoint, non-radiating, and anatomically consistent between individuals.[4][5][3]

Though initially considered somatic representations of neuro-lymphatic reflexes, the contributions of osteopathic physicians such as Charles Owens, DO, H.L. Samblanet, DO, and Paul Kimberly, DO, expanded the consideration of these nodules to be somatic manifestations of general visceral dysfunction, including of the lymphatics and endocrine glands.[6] Eventually, these nodules were coined Chapman's points or Chapman's reflexes.

This article intends to expand on issues of concern regarding Chapman's points, their embryologic basis, mechanism of development, and function in clinical practice.

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

An issue of great concern to the osteopathic community is the minimal collection of peer-reviewed clinical research regarding the physiology and presence of Chapman's points. Currently, much of the information about Chapman's points are anecdotal and based heavily on the clinical observations of a limited number of physicians. As of yet, there is no evidence confirming the presence of Chapman's points in tissue biopsies, but there exists a few studies demonstrating that sympathetic and endocrine alterations occur after rotatory manipulation of Chapman's points. The findings of these studies support the hypothesized physiology and presence of Chapman's points, as will be explained further in successive sections.[7][4]

Despite the minimal research into their physiology, Chapman's points are included in the curricula of osteopathic medical schools. Education of future osteopathic physicians of Chapman's points fosters the opportunity for future research that may ameliorate some of the allusiveness of these nodules.

Dr. Chapman left no written legacy regarding the reflex point interpretation system, but his brother-in-law, Charles Owens, D.O., and his wife, Ada Hinchley Chapman D.O., published the only existing text on this topic.

Development

During fetal development, autonomic efferents arise within the ventral ventricular zone, an anterior region of the primordial spinal cord. The primordial cells migrate toward the ventral horn and temporarily coalesce with somatic efferents, forming a singular primordial motor column. Eventually, the autonomic efferents will separate from the somatic efferents and migrate dorsally. Once in the intermediate spinal cord, the cell bodies of the autonomic efferents increase their polarity and fix their orientation within the gray matter, thus establishing their permanent placement within the intermediolateral columns (IML).[8] This temporary primordial motor column provides an opportunity for the intersection of visceral and somatic signaling, thereby laying the foundation for an embryologic basis of future reflex arcs connecting visceral and somatic systems.

The IML is located within the spinal cord gray matter from T1 to L2 with projections peripherally via sympathetic nerves, and the central nervous system. Collectively, the IML houses cell bodies of the preganglionic sympathetic efferents and is therefore responsible for sympathetic output to the viscera, including the lymphatics. The diagnostic utility of Chapman's points lies in the relatively distinct innervation of each viscus. Each structure transmits information to and from the central nervous system via a relatively homogenous segment of the spinal cord, resulting in somatic findings, such as the nodules of Chapman's points, within related dermatomal regions specific to the underlying dysfunctional viscus.[9]

After exiting the IML, preganglionic sympathetic efferents enter the sympathetic chain ganglia that lie alongside the vertebral column and synapse. From here, postganglionic sympathetic efferents branch and run alongside the ribs with the intercostal neurovascular bundle. These sympathetic branches are responsible for the sympathetic innervation of the arteries, veins, and lymphatic tissue contained within the bundle, which lies between the anterior and posterior layers of the intercostal fascia.[10]

Organ Systems Involved

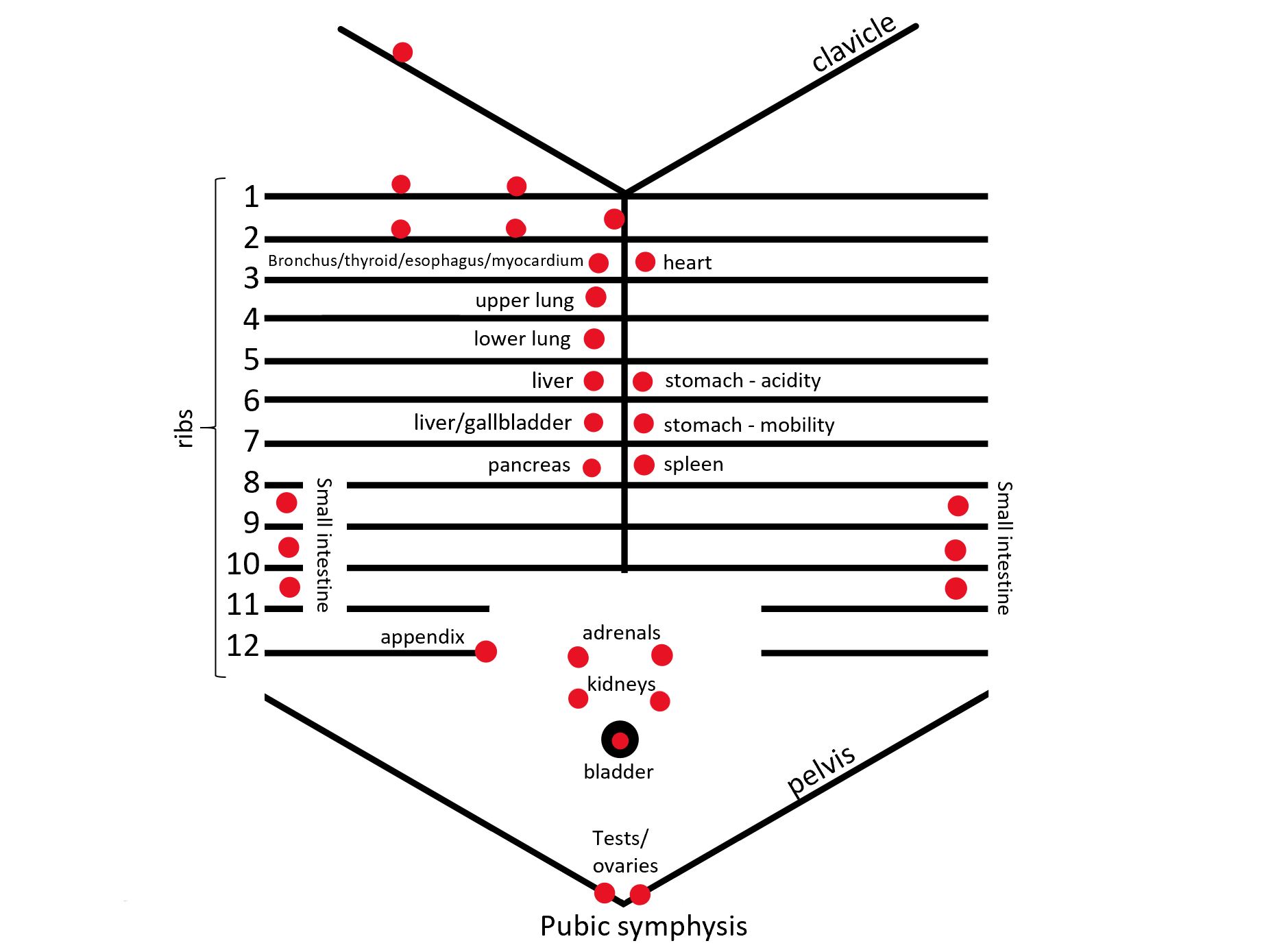

A conceptualized diagram of the locations of commonly encountered anterior Chapman’s points appears below. Additionally, this review includes a table of selected Chapman’s points. While unnecessary to memorize, familiarity with the location of these major anterior Chapman’s points can be of diagnostic utility to osteopathic physicians.

Function

Presently, there is no definitive consensus or guidelines regarding the function and value of Chapman's points. If utilized, most osteopathic physicians consider the finding of a Chapman's point a diagnostic tool. When considered concurrently with information gathered via a thorough history and physical, the presence of Chapman's points increases the clinical suspicion for underlying visceral disease.[7] While this diagnostic utility is agreed upon by many osteopathic physicians, the presence of a Chapman's point alone is never considered sufficient for diagnosis. A much smaller subset of osteopathic physicians uses rotary manipulation to treat Chapman's points as the hypothesis is to balance autonomic tone to related lymphatics and viscera, which may encourage lymphatic drainage and minimization of visceral dysfunction.[3][5]

Another hypothesis to consider for the identity of these ganglionic formations may be due to the presence of vessels of the system known as the "primo vascular system" (PVS). PVS have vessels and nodes from the surface to the periphery, connected to all the viscera and ubiquitously present in the human body. The liquid that these vessels carry is rich in protein, hormones, and more. The movement is influenced by the structures adjacent to the PVS, by the heartbeat and by the breath; moreover, the same vessels can contract, having their own electrical activity, through endothelial cells similar to the actin of smooth muscle. The liquid transport speed can be slower than the lymphatic transport speed or faster; this will depend on the location where PVS is present.

Mechanism

Chapman’s points are easily defined clinically, but physiologically they are much more complex. Visceral inflammation, spasm, and distention are all postulates as causes of positive Chapman’s points. The leading theory is that Chapman’s points develop from lymphatic dysfunction, secondary to underlying visceral dysfunction. Accordingly, Chapman’s points are broadly referred to as examples of viscero-somatic reflexes.[11][6]

Currently, the best hypothesis for the development of Chapman’s points lies in central sensitization and the facilitation of interneurons within the spinal cord gray matter. Visceral dysfunction, in the form of infection, inflammation, ischemia, etc. activate visceral afferent receptors, resulting in the transmission of abnormal or excessive input into the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. This abnormal input sensitizes the interneurons to subsequent stimuli. This facilitation maintains the interneurons at sub-threshold excitation, meaning that normal input to these interneurons is now amplified and results in excessive efferent responses.[2][12][13] In the case of Chapman’s points, the most important of these efferent responses is via the sympathetic signal back to the dysfunctional organ and surrounding lymphatic tissue.[14] It is suspected that this altered sympathetic tone results in dysfunction of the lymphatic tissues and creates gangliform contractions that impede lymphatic flow, which may exacerbate the preexisting visceral dysfunction and create inflammation distal to the contraction.[7]

While a variety of underlying visceral dysfunctions appear to cause Chapman’s points, they are most specifically representations of neuro-lymphatic reflexes.[7] Lymphatic capillaries receive input from the sympathetic nervous system. Activation of alpha-adrenergic receptors by epinephrine initially induces constriction and peristalsis of lymphatic channels. With sustained hyper-sympathetic stimulation, as occurs with visceral dysfunction, peristalsis decreases and results in stasis of lymph. This stasis exacerbates the underlying visceral dysfunction and induces positive feedback on the viscero-somatic reflex arc.[15][16][17] Further evidence of this neuro-lymphatic etiology lies in that Chapman’s points commonly present at the cutaneous vascular-lymphatic and cutaneous nerve interface.[18]

Another possible physiologic mechanism of Chapman’s points lies in the axon reflex. Sustained visceral dysfunction repeatedly depolarizes the visceral afferent receptors, triggering the release of neuropeptides. These neuropeptides stimulate C-fibers, resulting in depolarization and an action potential along sympathetic afferents. This sensory input into the CNS can establish central sensitization and/or maintain facilitation resulting from mechanisms discussed above. Additionally, the neuropeptides stimulate antidromic activity within nerve branches in sites unrelated to the underlying visceral dysfunction. This mechanism may explain Chapman’s points in seemingly unrelated areas.[19]

Related Testing

When screening for Chapman's points, it is important to note that there are both anterior and posterior points. In general, anterior Chapman's points are found in the intercostal space between segmentally related ribs, near the sternocostal or costochondral junctions. Posterior points typically appear between the spinous and transverse processes of vertebrae of the same numbered ribs as the anterior points. For example, innervation to and from the heart is routed via the gray matter of spinal cord levels T1-T5. The anterior point is found in the intercostal space between ribs 2 and 3 at the sternocostal junction, and the posterior point is present midway between the transverse and spinous processes of T2 and T3.[4]

Osteopathic physicians that include Chapman's points in their development of differential diagnoses often use a 30- or 45-second screen, in which they systematically screen for positive Chapman's points related to common pathologies. Studies have shown that including a Chapman's screen increases the credibility of a diagnosis.[7]

It is necessary clinically to differentiate Chapman's points from myofascial trigger points, Jones' strain-counterstrain tender points, and fibromyalgia points, which can all present similarly. Myofascial trigger points are present within taut bands of skeletal muscle or the muscle fascia. Trigger points elicit pain that radiates in specific, reproducible patterns when compressed.[20][21][22] Jones' strain-counterstrain tender points are simply points of tenderness, without other somatic findings like the nodularity of Chapman's points. Named by Lawrence Jones, DO, counter strain tender points occur in muscles that aberrantly signal strain to the central nervous system in the absence of physical strain. These points are used entirely for the treatment of somatic dysfunction using counterstrain (also referred to as strain-counterstrain).[23][24] Fibromyalgia points are also points of tenderness that are used for the diagnosis of fibromyalgia. One of the diagnostic sets of criteria for fibromyalgia requires the presence of widespread chronic pain and the presence of 11 of 18 of these tender points.[25]

To diagnose a positive Chapman's point, the anterior and corresponding posterior point both need to be present, despite the general use of posterior points for treatment. Furthermore, a reference chart, similar to those included at the conclusion of this article, should be used when screening.[4]

While diagnostically valuable, the presence of Chapman's points should be considered in light of all information gleaned from a full structural exam, history, and physical.[7] For example, a physician should also screen for other viscero-somatic reflex findings in related tissues. For instance, if a patient presents with colicky right upper quadrant pain that is exacerbated by fatty meals, it is likely a physician will find a gallbladder Chapman's point in the intercostal space between ribs 5 and 6 on the right along with hypertonicity of the paraspinal musculature from T5 to T9 on the right. The presence of a gallbladder Chapman's points and viscero-somatic reflex tissue texture changes in tissues segmentally related to the gallbladder lead the physician to assume biliary pathology. When considered in conjunction with the patient's history, there is high clinical suspicion of cholelithiasis.

Clinical Significance

Because Chapman's points are somatic representations of viscero-somatic reflexes, they are typically used diagnostically, rather than therapeutically, and provide further clinical evidence of the presence or absence of visceral disease.[6][7] When taken in context with other findings elucidated during a patient visit, Chapman's points can contribute to a physician's differential diagnosis. Many osteopathic leaders indicate that a non-tender Chapman's point alone is indicative of nothing and that a diagnosis can never be made based solely on the presence of a non-tender Chapman's point. Despite this, they also encourage physicians never to ignore or trivialize the presence of a tender Chapman's point, unless the physician can provide a sound explanation for the finding, especially when the point is persistently tender.[6]

If a physician does decide to use a Chapman's point for treatment, rotatory movement over the point is believed to normalize the autonomic tone of the associated dysfunctional viscera by decreasing sympathetic input to the visceral structure.[3][6] While there is currently no research supporting this mechanism exactly, studies have shown that rotary manipulation of the suboccipital region dampens sympathetic outflow, indicated by a lowered heart rate in test subjects.[26]

These findings support the potential for the treatment of Chapman's points to alter the sympathetic tone to associated structures. There is also a belief that the treatment of Chapman's points improves lymphatic return and maximizes myofascial motion surrounding the dysfunctional viscera. Again, there is currently no evidence directly supporting this theory, but studies have found that manipulation of lymphatic channels via rhythmic compression of the abdomen or thorax has increased flow through the thoracic duct and increased the leukocyte count of the lymphatic fluids, even at distant sites.

Assuming that Chapman's points are, in fact, due to gangliform contractions within lymphatic tissues, these findings support that manipulation of lymphatic tissues, by rotary manipulation of Chapman's points in this case, mobilizes immune cells and may aid in disease recovery.[27][28][5] To sufficiently treat a Chapman's point, especially a posterior point located within paraspinal musculature or a particularly painful point, treatment of the overlying tissues to reduce tissue texture changes may be necessary before treating the actual point.[29]

Taking up the theory of developing PVS, other authors relate Chapman's points to this system.[30][31] The PVS would be related to the meridians, and, as a hypothesis, the Chapman points could be the same points where Chinese medicine identifies the areas of insertion of the needles.[30]

To conclude, one must remember that the lack of strong evidence does not mean that the phenomenon does not exist. EBM is a tripod in perfect balance: clinical experience, patient response to treatment, research. These three branches have equal value.[32]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Brown T, Celander E, Celander DR. A proposed mechanism for osteopathic manipulative therapy effects on blood pressure. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 1970 Jun:69(10):1035-6 passim [PubMed PMID: 5201424]

Chin J, Francis M, Lavalliere JM, Lomiguen CM. Osteopathic Physical Exam Findings in Chronic Hepatitis C: A Case Study. Cureus. 2019 Jan 22:11(1):e3939. doi: 10.7759/cureus.3939. Epub 2019 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 30937237]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSpiegel AJ, Capobianco JD, Kruger A, Spinner WD. Osteopathic manipulative medicine in the treatment of hypertension: an alternative, conventional approach. Heart disease (Hagerstown, Md.). 2003 Jul-Aug:5(4):272-8 [PubMed PMID: 12877760]

Davis SE, Hendryx J, Bouwer S, Menezes C, Menezes H, Patel V, Speelman DL. Correlation Between Physiologic and Osteopathic Measures of Sympathetic Activity in Women With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2019 Jan 1:119(1):7-17. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2019.004. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30615047]

Degenhardt BF, Kuchera ML. Update on osteopathic medical concepts and the lymphatic system. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 1996 Feb:96(2):97-100 [PubMed PMID: 8838905]

Chikly BJ. Manual techniques addressing the lymphatic system: origins and development. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2005 Oct:105(10):457-64 [PubMed PMID: 16314678]

Washington K, Mosiello R, Venditto M, Simelaro J, Coughlin P, Crow WT, Nicholas A. Presence of Chapman reflex points in hospitalized patients with pneumonia. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2003 Oct:103(10):479-83 [PubMed PMID: 14620082]

Markham JA, Vaughn JE. Migration patterns of sympathetic preganglionic neurons in embryonic rat spinal cord. Journal of neurobiology. 1991 Nov:22(8):811-22 [PubMed PMID: 1779224]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBeal MC. Viscerosomatic reflexes: a review. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 1985 Dec:85(12):786-801 [PubMed PMID: 3841111]

Jetti R, Kadiyala B, Bolla SR. Anatomy, Back, Lumbar Sympathetic Chain. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969736]

Liem T. A.T. Still's Osteopathic Lesion Theory and Evidence-Based Models Supporting the Emerged Concept of Somatic Dysfunction. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2016 Oct 1:116(10):654-61. doi: 10.7556/jaoa.2016.129. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27669069]

Luz LL, Fernandes EC, Sivado M, Kokai E, Szucs P, Safronov BV. Monosynaptic convergence of somatic and visceral C-fiber afferents on projection and local circuit neurons in lamina I: a substrate for referred pain. Pain. 2015 Oct:156(10):2042-2051. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000267. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26098437]

Jänig W. Neuronal mechanisms of pain with special emphasis on visceral and deep somatic pain. Acta neurochirurgica. Supplementum. 1987:38():16-32 [PubMed PMID: 3307313]

Silva ACO, Biasotto-Gonzalez DA, Oliveira FHM, Andrade AO, Gomes CAFP, Lanza FC, Amorim CF, Politti F. Effect of Osteopathic Visceral Manipulation on Pain, Cervical Range of Motion, and Upper Trapezius Muscle Activity in Patients with Chronic Nonspecific Neck Pain and Functional Dyspepsia: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Pilot Study. Evidence-based complementary and alternative medicine : eCAM. 2018:2018():4929271. doi: 10.1155/2018/4929271. Epub 2018 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 30534176]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMohanakumar S, Majgaard J, Telinius N, Katballe N, Pahle E, Hjortdal V, Boedtkjer D. Spontaneous and α-adrenoceptor-induced contractility in human collecting lymphatic vessels require chloride. American journal of physiology. Heart and circulatory physiology. 2018 Aug 1:315(2):H389-H401. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00551.2017. Epub 2018 Apr 6 [PubMed PMID: 29631375]

D'Andrea V, Bianchi E, Taurone S, Mignini F, Cavallotti C, Artico M. Cholinergic innervation of human mesenteric lymphatic vessels. Folia morphologica. 2013 Nov:72(4):322-7 [PubMed PMID: 24402754]

Korr IM. The spinal cord as organizer of disease processes: III. Hyperactivity of sympathetic innervation as a common factor in disease. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 1979 Dec:79(4):232-7 [PubMed PMID: 583147]

Patriquin DA. The evolution of osteopathic manipulative technique: the Spencer technique. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 1992 Sep:92(9):1134-6, 1139-46 [PubMed PMID: 1429074]

Groetzner P, Weidner C. The human vasodilator axon reflex - an exclusively peripheral phenomenon? Pain. 2010 Apr:149(1):71-75. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.01.012. Epub 2010 Feb 6 [PubMed PMID: 20138429]

Hsieh CY, Hong CZ, Adams AH, Platt KJ, Danielson CD, Hoehler FK, Tobis JS. Interexaminer reliability of the palpation of trigger points in the trunk and lower limb muscles. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2000 Mar:81(3):258-64 [PubMed PMID: 10724067]

McPartland JM. Travell trigger points--molecular and osteopathic perspectives. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2004 Jun:104(6):244-9 [PubMed PMID: 15233331]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMelzack R, Stillwell DM, Fox EJ. Trigger points and acupuncture points for pain: correlations and implications. Pain. 1977 Feb:3(1):3-23. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90032-X. Epub [PubMed PMID: 69288]

Wynne MM, Burns JM, Eland DC, Conatser RR, Howell JN. Effect of counterstrain on stretch reflexes, hoffmann reflexes, and clinical outcomes in subjects with plantar fasciitis. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2006 Sep:106(9):547-56 [PubMed PMID: 17079524]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSnider KT, Johnson JC. Survey of billing and coding for counterstrain tender points. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 2012 Jun:112(6):356-65 [PubMed PMID: 22707645]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceClauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: a clinical review. JAMA. 2014 Apr 16:311(15):1547-55. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.3266. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24737367]

Purdy WR, Frank JJ, Oliver B. Suboccipital dermatomyotomic stimulation and digital blood flow. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 1996 May:96(5):285-9 [PubMed PMID: 8936445]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceHodge LM, King HH, Williams AG Jr, Reder SJ, Belavadi T, Simecka JW, Stoll ST, Downey HF. Abdominal lymphatic pump treatment increases leukocyte count and flux in thoracic duct lymph. Lymphatic research and biology. 2007:5(2):127-33 [PubMed PMID: 17935480]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDery MA, Yonuschot G, Winterson BJ. The effects of manually applied intermittent pulsation pressure to rat ventral thorax on lymph transport. Lymphology. 2000 Jun:33(2):58-61 [PubMed PMID: 10897471]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcMakin CR,Oschman JL, Visceral and somatic disorders: tissue softening with frequency-specific microcurrent. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.). 2013 Feb [PubMed PMID: 22775307]

Caso ML. Evaluation of Chapman's neurolymphatic reflexes via applied kinesiology: a case report of low back pain and congenital intestinal abnormality. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2004 Jan:27(1):66 [PubMed PMID: 14739884]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGin RH, Green BN. George Goodheart, Jr., D.C., and a history of applied kinesiology. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 1997 Jun:20(5):331-7 [PubMed PMID: 9200049]

Bordoni B. The Benefits and Limitations of Evidence-based Practice in Osteopathy. Cureus. 2019 Nov 7:11(11):e6093. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6093. Epub 2019 Nov 7 [PubMed PMID: 31857925]