Introduction

Tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) is a severe complication of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) that primarily affects sexually active women of reproductive age, although it may occur without other PID sequelae. This condition is characterized by adnexal inflammation, typically involving pus-filled fallopian tubes and ovaries, caused by an ascending infection from the upper genital tract. TOA can lead to systemic infections and impact nearby organs, such as the bowel or bladder, with mortality rates reaching up to 12% before the advent of antibiotic treatment.[1] Common symptoms include fever, abdominal pain, and foul-smelling vaginal discharge, with diagnosis supported by imaging showing fluid-filled, inflamed tubes or abscesses. However, the clinical presentation can vary widely.

TOA presents serious risks, including infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and a heightened risk of ectopic pregnancy. A ruptured abscess can result in life-threatening sepsis, underscoring the need for prompt evaluation and treatment at the first clinical suspicion.[2][3][4] Initial management typically involves broad-spectrum antibiotics, which are effective in many cases. However, larger abscesses or those unresponsive to antibiotics within 72 hours may require surgical intervention or image-guided drainage.[5] Surgical approaches vary and include laparoscopy or laparotomy, with considerations based on factors such as abscess size, patient age, fertility considerations, and surgical history.

Image-guided drainage, such as transvaginal aspiration, is a minimally invasive treatment option with high success rates, especially for smaller abscesses.[6] However, larger or more complex abscesses may require catheter drainage or surgical intervention. The decision between antibiotics, drainage, and surgery depends on factors such as the severity of the infection and the patient’s overall health.[7] Despite advancements in treatment, delayed diagnosis or improper management can lead to long-term complications, including the need for more radical surgical procedures such as salpingo-oophorectomy or, in severe cases, hysterectomy.[8]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

TOA often results from untreated PID, which typically begins with a lower genital tract infection that ascends into the fallopian tubes and ovaries. As a result, infectious pathogens are the most common cause of TOAs. However, the specific organisms identified in TOA differ from the typical pathogens associated with PID. In premenopausal women, sexually transmitted pathogens such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae are commonly reported.[9] However, Escherichia coli, Bacteroides fragilis, and Peptostreptococcus species are more frequently found in TOA, especially in postmenopausal women.[9][10]

TOA infections are generally polymicrobial, involving a combination of enteric, respiratory, and anaerobic bacteria, with less frequent involvement of traditional sexually transmitted pathogens. Emerging pathogens such as Mycoplasma genitalium have been identified as contributors to PID, but standard antibiotic regimens may not fully target this organism. Rarely, organisms such as Mycobacterium and Actinomyces can also lead to TOA in specific cases.[1][11] Additionally, TOAs can also result from the spread of infection from an adjacent organ, most commonly the appendix. Less frequently, they may arise from hematogenous dissemination from a distant infection site or be associated with pelvic organ malignancies.[12][13]

Tubo-Ovarian Abscess Risk Factors

The primary risk factors for PID, and consequently TOA, include:

- Age 25 and younger

- Multiple or new sexual partners

- Placement or removal of an intrauterine contraceptive device

- Endometrial biopsy

- In vitro fertilization

- Unprotected intercourse

- Sexual activity beginning before age 15

- History of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), such as C trachomatis and N gonorrhoeae [6][14]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of PID in females in the United States is estimated to exceed 2 million cases.[15] PID occurs most frequently among non-Hispanic Black women residing in Southern states.[15] Sexually transmitted and commensal vaginal pathogens are implicated in over 85% of PID cases, while respiratory and intestinal colonizing organisms account for the remaining incidences of PID. Notably, TOAs are predominantly polymicrobial in nature.[1]

Approximately 15% to 35% of patients hospitalized for PID develop TOAs.[14][8] TOAs are less prevalent in postmenopausal women, who account for 6% to 18% of cases.[11] Mortality rates associated with TOAs have significantly declined with the advent of effective antibiotic regimens, now estimated at approximately 1 in 740 cases.[1]

Pathophysiology

Organisms from the lower genital tract typically ascend following inflammatory epithelial damage, forming an inflammatory mass that involves the fallopian tube, ovary, and sometimes adjacent pelvic organs. Infections, including tubercular organisms, can also reach the upper genital tract via lymphatic or hematogenous pathways.[1][6] Please refer to the Epidemiology section for more information.

History and Physical

Due to the shared underlying etiologies of TOA and PID, and the fact that PID often leads to TOAs, the recommended diagnostic evaluation is similar, with additional procedures used in patients suspected of having TOAs or presenting with nonspecific or atypical findings. However, diagnosing both TOA and PID can be challenging due to the wide variability in clinical presentations. Many women with PID exhibit subtle or nonspecific symptoms, making early detection difficult.[6] Delayed diagnosis can result in severe complications, including infertility, ectopic pregnancy, and chronic pelvic pain.[5][13]

Clinical History

The clinical diagnosis of PID is primarily based on symptom assessment. A classical presentation of a TOA includes abdominal pain, a pelvic mass on examination, fever, and leukocytosis. Studies suggest that the positive predictive value of a clinical diagnosis of PID ranges from 65% to 90% when compared to laparoscopy.[5][13] The accuracy of this diagnosis is influenced by epidemiological factors, such as the prevalence of STIs in specific populations, particularly sexually active young women, adolescents, and high-risk communities. Due to the limitations of clinical diagnosis, it is essential for clinicians to consider risk factors such as age, sexual activity, and a history of STIs. In populations with a high prevalence of STIs, the positive predictive value of a clinical PID diagnosis is higher.[5]

Common symptoms of PID include lower abdominal pain, abnormal bleeding, dyspareunia, and vaginal discharge. In cases of TOA and severe PID, patients may also experience fever, bilateral pelvic pain (worse on one side), and right upper quadrant pain.[6] However, some cases go undiagnosed due to the mildness of symptoms or because both clinicians and patients may not recognize these symptoms as indicative of a severe condition.[5] Due to the potential for reproductive harm, a low threshold for the clinical diagnosis of PID is recommended, particularly in sexually active women.[10] Empiric treatment for PID is often initiated when a patient presents with pelvic or lower abdominal pain, other potential causes have been excluded, and one or more of the following clinical signs are evident—cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness.[5]

Clinical Examination

A comprehensive physical examination, including a detailed pelvic exam, is essential. In patients with clear signs of lower genitourinary infection, the pelvic exam typically reveals mucopurulent discharge, pelvic discomfort, and tenderness during cervical motion on bimanual examination. Additionally, patients may report symptoms such as fever, abnormal uterine bleeding, urinary complaints, or pain during intercourse. Pelvic tenderness, particularly when worsened on one side during palpation, along with adnexal mass and rectal discomfort, may suggest a TOA in a patient with suspected PID. Abdominal rigidity and signs of sepsis could indicate a ruptured TOA.[6][5][16]

When complications are suspected, laboratory tests or imaging studies can help guide treatment and management decisions, especially when assessing for a TOA. A bimanual exam is essential for detecting cervical, uterine, or adnexal tenderness, as well as masses or abscesses. A speculum exam can also confirm mucopurulent cervical discharge and cervical friability.[10][6][5] Therefore, the diagnosis of PID and TOA is primarily clinical, with additional tests reserved for complicated cases or when the diagnosis remains uncertain. A high index of suspicion and prompt initiation of treatment are critical to preventing long-term complications.[5][10]

Evaluation

Laboratory Studies

Urine pregnancy tests and urinalysis are essential to help rule out differential diagnoses.[10][6] Additional laboratory studies that should be performed to help assess for infectious etiologies and sepsis include a complete blood count, STI testing, blood cultures, and a wet prep of vaginal secretions. In cases where malignancy is suspected based on clinical features, tumor markers like cancer antigen 125 and alpha-fetoprotein should be considered.[7] Laboratory findings such as elevated C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), or positive results for gonorrhea and chlamydia can support a diagnosis of TOA.[5][10]

While no single clinical or laboratory finding is definitive for diagnosing PID, combining multiple diagnostic criteria can improve either sensitivity or specificity.[5] To improve the specificity of a PID diagnosis, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends considering the following additional supportive findings:

- Oral temperature above 101 °F (38.3 °C)

- Mucopurulent cervical discharge or cervical friability on examination

- Large numbers of white blood cells evident on saline microscopy of vaginal fluid

- Increased serum ESR

- Elevated serum CRP

- Laboratory confirmation of cervical infection with N gonorrhoeae or C trachomatis [5]

Diagnostic Imaging Studies

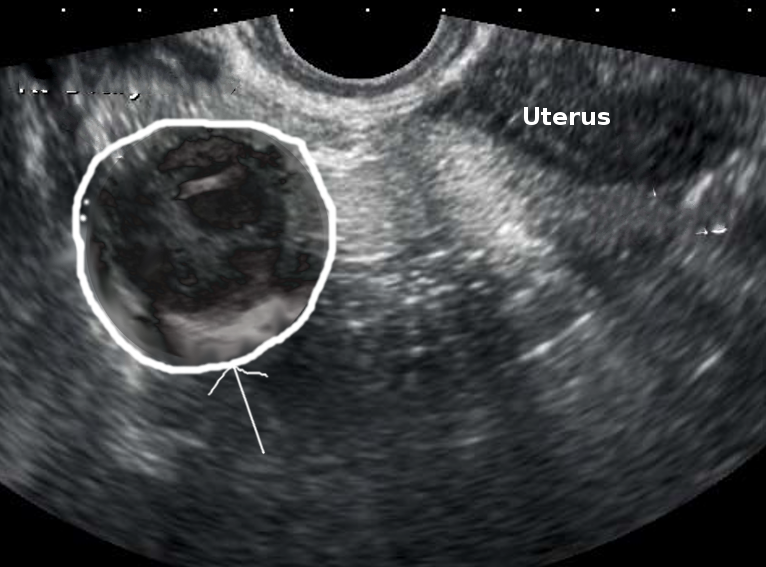

Diagnostic imaging studies, such as ultrasonography or computed tomography (CT), may be used when a TOA is suspected. Transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasonography are preferred as the initial imaging modalities to evaluate pelvic pain in reproductive-aged women (see Image. Right Tubo-Ovarian Abscess).[17] Ultrasonographic findings of a TOA may vary but typically include the loss of normal anatomical boundaries secondary to severe inflammatory changes, a heterogeneous complex, a fluid-filled irregular mass with septations, and loculated free fluid in the cul-de-sac.[17] However, several common inflammatory conditions, such as appendicitis and infectious enterocolitis, may produce ultrasonographic findings similar to those of a TOA, necessitating additional studies for confirmation.[18][16] Thickened, distended fallopian tubes are also more suggestive of a TOA.

If the initial ultrasonographic examination is inconclusive, CT is commonly used to further evaluate a suspected TOA.[16] A CT scan of a TOA may reveal a solid-cystic adnexal mass with thickened, irregularly enhancing walls and complex septated internal fluid. The mesosalpinx surrounding the TOA is often thickened, and the fallopian tube may appear dilated. Additional findings may include peritoneal free fluid, an enlarged and edematous ovary, periovarian fat stranding, and signs of reactive inflammation such as hydronephrosis, bowel wall thickening, and ileus.[19][16]

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is recommended when ultrasonographic and CT findings require further differentiation.[17] MRI is also preferred when additional imaging is needed, as tubal changes associated with TOA are more clearly visualized using various MRI techniques. These include septal and thick-rim mucosal enhancement with intravenous (IV) gadolinium and restricted diffusion due to purulent tubal content on diffusion-weighted imaging.[19]

Treatment / Management

Historically, TOAs were managed with a total abdominal hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.[20] However, treatment has evolved significantly with the development of broad-spectrum antibiotics and advancements in imaging and drainage techniques. Studies utilizing these management strategies report success rates of 70% or higher. Daily monitoring of leukocytosis with complete blood counts is recommended to assess treatment response.[21][22][23](B2)

Inpatient management and gynecological consultation are essential for any woman with a TOA. IV antibiotics are recommended as first-line therapy for unruptured TOAs, achieving effectiveness in 70% to 87% of cases.[8] Image-guide drainage or surgical intervention may be necessary based on clinical factors or the response to antibiotics.[7] Image-guided aspiration and laparoscopy can provide both diagnostic confirmation and treatment simultaneously. Laparoscopy remains the gold standard for confirming PID. While laparoscopy is a reliable tool for identifying salpingitis and offering a more accurate bacteriological diagnosis, its use is less frequent than more conservative methods due to its invasiveness and limited availability in some regions.[10][6]

Antibiotic Treatment Regimens for Tubo-Ovarian Abscess

Treatment of TOA typically involves IV antibiotics, which have demonstrated efficacy in randomized trials. Clinical improvement is usually expected within 24 to 48 hours, after which a transition to oral therapy may be considered. Inpatient monitoring for over 24 hours is recommended for patients with TOA.[5] The CDC recommends the following parenteral regimens:

- Ceftriaxone (1 g IV every 24 h) + doxycycline (100 mg orally/IV every 12 h) + metronidazole (500 mg orally/IV every 12 h)

- Cefotetan (2 g IV every 12 h) + doxycycline (100 mg orally/IV every 12 h)

- Cefoxitin (2 g IV every 6 h) + doxycycline (100 mg orally/IV every 12 h) [5]

Doxycycline should be administered orally whenever possible to avoid the discomfort associated with IV administration. Since oral and IV forms of doxycycline and metronidazole exhibit similar absorption, oral therapy is generally preferred for stable patients. Upon clinical improvement, treatment is transitioned to oral doxycycline and metronidazole, with a total therapy duration of at least 14 days.[5]

The CDC recommends the following alternative parenteral regimens, supported by limited data, for use when the preferred antibiotic regimen is contraindicated, such as in cases of patient allergy to specific components:

- Ampicillin-sulbactam (3 g IV every 6 h) + doxycycline (100 mg orally/IV every 12 h)

- Clindamycin (900 mg IV every 8 h) + gentamicin (2 mg/kg body weight as loading dose IV or intramuscular (IM), followed by 1.5 mg/kg every 8 h or daily dosing at 3-5 mg/kg) [5]

If patients show clinical improvement within 24 to 48 hours, a transition to oral antibiotics is appropriate to complete at least 14 days of treatment. Oral regimens should include clindamycin or metronidazole alongside doxycycline to ensure adequate anaerobic coverage. Percutaneous drainage or surgical intervention should be considered if no improvement is observed within 72 hours.[24][8][13] In patients with a worsening clinical condition suggestive of TOA rupture, such as increasing pain or signs of sepsis, laparoscopy should be promptly considered.[5][16](A1)

Procedural Therapeutic Approaches for Tubo-Ovarian Abscess

TOA management typically begins with antimicrobial therapy, reserving invasive procedures for suspected rupture or cases unresponsive to antibiotics after 72 hours.[20] Approximately 25% to 30% of patients fail to respond adequately to antibiotics, necessitating image-guided drainage or surgical intervention.[13] Studies have shown that TOAs measuring greater than or equal to 5.5 cm are more likely to require invasive therapy compared to those less than or equal to 5 cm.[8][25] The incidence of antibiotic treatment failure is also higher in older women and those with elevated white blood cell counts (>16,000/µL), elevated CRP and ESR levels, and temperatures more than 38 °C.[13][8]

Therapeutic procedures for draining TOAs more than 3 cm may include percutaneous catheter drainage or surgical approaches.[26] While surgery was historically the recommended treatment approach, recent evidence suggests that image-guided drainage is equally effective.[13] Neither procedure is currently favored over the other, so the choice should depend on clinician preference and clinical factors, such as reproductive status.[25][13][7]

Image-guided percutaneous catheter drainage: When selecting percutaneous catheter drainage for a TOA, the route and technique depend on the clinician's preference and clinical factors, such as the patient's body habitus, as well as the size and location of the TOA. Common routes for percutaneous catheter drainage include transabdominal, transgluteal, transrectal, transvaginal, transperineal, and transvesicular, with studies showing effectiveness for each. Transabdominal and transgluteal routes are generally recommended due to their sterility compared to other methods.[26] Please see StatPearls' companion resource, "Percutaneous Abscess Drainage," for more information.

Surgical intervention: A ruptured TOA or deterioration of a patient's condition suggestive of sepsis requires emergent surgical treatment for washout and evaluation of the peritoneal cavity. Both laparoscopic and laparotomy approaches may be used, though laparotomy is more commonly preferred due to the extensive adhesions and anatomical distortion often associated with TOAs. Laparoscopy is preferred if a surgeon with advanced minimally invasive surgical skills is available.[25][27][8][26] Surgical management is also recommended for postmenopausal women due to the increased risk of an occult malignancy.[7] Copious irrigation, microbial cultures, and excision of the abscess cavity should be performed. For patients who have completed childbearing, a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy may be considered, while salpingo-oophorectomy is preferred for those desiring fertility conservation.[8] A closed suction drain should be placed to monitor postsurgical drainage.[26]

Other Treatment Considerations

Women should refrain from sexual activity until treatment is completed, symptoms have resolved, and partners are treated. Testing for STIs, including gonorrhea, chlamydia, HIV, and syphilis, is recommended, though the value of testing for M genitalium remains uncertain. Retesting for gonorrhea and chlamydia is advised 3 months posttreatment or at the next medical visit.[5]

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis for TOA often includes:

- Renal stone

- Appendicitis

- Cholecystitis

- Inguinal hernia

- Obturator hernia

- Bowel obstruction

- Diverticulitis

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Pelvic inflammatory disease

- Ovarian torsion

- Ectopic pregnancy

- Ruptured ovarian cyst

- Pyelonephritis

- Cystitis [7]

Prognosis

The prognosis for TOA is generally favorable with prompt and appropriate treatment. Most patients experience clinical improvement within 24 to 48 hours of receiving parenteral antibiotics, followed by oral therapy.[5] Approximately 70% of patients achieve resolution of the TOA with antibiotic treatment alone.[13]

Reproductive implications of TOAs, such as ectopic pregnancy and infertility, can be significant. One study found that only 7.5% of patients with a TOA reported subsequent pregnancy.[5][1] However, early recognition and timely intervention, including more invasive treatments, can improve fertility outcomes. Pregnancy rates range from 32% to 63% in patients treated with antibiotics and laparoscopic drainage.[25]

Complications

Complications of TOA include:

- Chronic pelvic pain

- Sepsis

- Distortion of the pelvic anatomy

- Increased risk of ectopic pregnancy

- Infertility

- Recurrent PID

- Peritoneal adhesions [25][5]

Complications associated with TOA treatment include:

- Septic shock

- Bacteremia

- Allergic reaction

- Bowel injury

- Hemorrhage [28]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Effective management of a TOA requires an interprofessional healthcare team approach due to its complex presentation, which can be confused with conditions such as appendicitis, ureteral stones, cystitis, or obturator hernia. Delayed treatment can result in severe morbidity, making timely diagnosis and intervention crucial. Physicians, advanced practitioners, nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare professionals must collaborate closely to improve patient-centered care, safety, and outcomes.

In many cases, patients with TOA first present to the emergency department, making the triage nurse's role crucial. Nurses must quickly recognize symptoms of TOA, ensure prompt admission, and notify the physician or advanced practitioner immediately. A gynecologist should be consulted when TOA is suspected to ensure appropriate management. Radiologists and interventional radiologists are critical in confirming the diagnosis and performing therapeutic drainage through imaging. Once diagnosed, swift coordination among all involved disciplines is essential to prevent complications and optimize patient outcomes.

Nurses are also instrumental in patient education, particularly regarding prevention. They should educate patients about risk factors such as unprotected sex and multiple sexual partners, encouraging safe sex practices and condom use to reduce the risk of conditions that may lead to TOA. Pharmacists and infectious disease specialists contribute by recommending an appropriate antibiotic regimen and promoting adherence to prescribed antibiotics, which is essential for the resolution of the abscess and for preventing long-term sequelae.

Effective communication among healthcare team members is crucial for improving patient outcomes. Clear and consistent communication ensures that all healthcare professionals are aligned in their approach, reducing the risk of complications such as infertility, pelvic thrombophlebitis, and chronic pelvic pain. In the event of a TOA rupture, which constitutes a surgical emergency, prompt and coordinated action is necessary to prevent life-threatening sepsis and death. By collaborating and staying informed, the interprofessional team can deliver comprehensive, patient-centered care, optimizing both short-term and long-term health outcomes for patients with TOA.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Tang H, Zhou H, Zhang R. Antibiotic Resistance and Mechanisms of Pathogenic Bacteria in Tubo-Ovarian Abscess. Frontiers in cellular and infection microbiology. 2022:12():958210. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.958210. Epub 2022 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 35967860]

Tao X, Ge SQ, Chen L, Cai LS, Hwang MF, Wang CL. Relationships between female infertility and female genital infections and pelvic inflammatory disease: a population-based nested controlled study. Clinics (Sao Paulo, Brazil). 2018 Aug 9:73():e364. doi: 10.6061/clinics/2018/e364. Epub 2018 Aug 9 [PubMed PMID: 30110069]

Fouks Y, Cohen A, Shapira U, Solomon N, Almog B, Levin I. Surgical Intervention in Patients with Tubo-Ovarian Abscess: Clinical Predictors and a Simple Risk Score. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2019 Mar-Apr:26(3):535-543. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.06.013. Epub 2018 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 29966713]

Fouks Y, Cohen Y, Tulandi T, Meiri A, Levin I, Almog B, Cohen A. Complicated Clinical Course and Poor Reproductive Outcomes of Women with Tubo-Ovarian Abscess after Fertility Treatments. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2019 Jan:26(1):162-168. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2018.06.004. Epub 2018 Jun 8 [PubMed PMID: 29890350]

Workowski KA, Bachmann LH, Chan PA, Johnston CM, Muzny CA, Park I, Reno H, Zenilman JM, Bolan GA. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021. MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports. 2021 Jul 23:70(4):1-187. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.rr7004a1. Epub 2021 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 34292926]

Curry A, Williams T, Penny ML. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention. American family physician. 2019 Sep 15:100(6):357-364 [PubMed PMID: 31524362]

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Gynecology. Practice Bulletin No. 174: Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Nov:128(5):e210-e226 [PubMed PMID: 27776072]

Yagur Y, Weitzner O, Shams R, Man-El G, Kadan Y, Daykan Y, Klein Z, Schonman R. Bilateral or unilateral tubo-ovarian abscess: exploring its clinical significance. BMC women's health. 2023 Dec 19:23(1):678. doi: 10.1186/s12905-023-02826-x. Epub 2023 Dec 19 [PubMed PMID: 38115034]

Al-Kuran OA, Al-Mehaisen L, Al-Karablieh M, Abu Ajamieh M, Flefil S, Al-Mashaqbeh S, Albustanji Y, Al-Kuran L. Gynecologists and pelvic inflammatory disease: do we actually know what to do?: A cross-sectional study in Jordan. Medicine. 2023 Oct 6:102(40):e35014. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000035014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 37800796]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYusuf H, Trent M. Management of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in Clinical Practice. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2023:19():183-192. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S350750. Epub 2023 Feb 15 [PubMed PMID: 36814428]

Gil Y, Capmas P, Tulandi T. Tubo-ovarian abscess in postmenopausal women: A systematic review. Journal of gynecology obstetrics and human reproduction. 2020 Nov:49(9):101789. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2020.101789. Epub 2020 May 13 [PubMed PMID: 32413520]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceInal ZO, Inal HA, Gorkem U. Experience of Tubo-Ovarian Abscess: A Retrospective Clinical Analysis of 318 Patients in a Single Tertiary Center in Middle Turkey. Surgical infections. 2018 Jan:19(1):54-60. doi: 10.1089/sur.2017.215. Epub 2017 Nov 17 [PubMed PMID: 29148955]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChan GMF, Fong YF, Ng KL. Tubo-Ovarian Abscesses: Epidemiology and Predictors for Failed Response to Medical Management in an Asian Population. Infectious diseases in obstetrics and gynecology. 2019:2019():4161394. doi: 10.1155/2019/4161394. Epub 2019 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 31274977]

Gao Y, Qu P, Zhou Y, Ding W. Risk factors for the development of tubo-ovarian abscesses in women with ovarian endometriosis: a retrospective matched case-control study. BMC women's health. 2021 Jan 30:21(1):43. doi: 10.1186/s12905-021-01188-6. Epub 2021 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 33516203]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKreisel KM, Llata E, Haderxhanaj L, Pearson WS, Tao G, Wiesenfeld HC, Torrone EA. The Burden of and Trends in Pelvic Inflammatory Disease in the United States, 2006-2016. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2021 Aug 16:224(12 Suppl 2):S103-S112. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa771. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34396411]

Taylor GM, Erlich AH, Wallace LC, Williams V, Ali RM, Zygowiec JP. A tubo-ovarian abscess mimicking an appendiceal abscess: a rare presentation of Streptococcus agalactiae. Oxford medical case reports. 2019 Aug 1:2019(8):. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omz071. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31398722]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceExpert Panel on GYN and OB Imaging, Brook OR, Dadour JR, Robbins JB, Wasnik AP, Akin EA, Borloz MP, Dawkins AA, Feldman MK, Jones LP, Learman LA, Melamud K, Patel-Lippmann KK, Saphier CJ, Shampain K, Uyeda JW, VanBuren W, Kang SK. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Acute Pelvic Pain in the Reproductive Age Group: 2023 Update. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2024 Jun:21(6S):S3-S20. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2024.02.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38823952]

Revzin MV, Moshiri M, Katz DS, Pellerito JS, Mankowski Gettle L, Menias CO. Imaging Evaluation of Fallopian Tubes and Related Disease: A Primer for Radiologists. Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2020 Sep-Oct:40(5):1473-1501. doi: 10.1148/rg.2020200051. Epub 2020 Aug 21 [PubMed PMID: 32822282]

Foti PV, Tonolini M, Costanzo V, Mammino L, Palmucci S, Cianci A, Ettorre GC, Basile A. Cross-sectional imaging of acute gynaecologic disorders: CT and MRI findings with differential diagnosis-part II: uterine emergencies and pelvic inflammatory disease. Insights into imaging. 2019 Dec 20:10(1):118. doi: 10.1186/s13244-019-0807-6. Epub 2019 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 31858287]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLareau SM, Beigi RH. Pelvic inflammatory disease and tubo-ovarian abscess. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2008 Dec:22(4):693-708. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2008.05.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18954759]

Brun JL, Graesslin O, Fauconnier A, Verdon R, Agostini A, Bourret A, Derniaux E, Garbin O, Huchon C, Lamy C, Quentin R, Judlin P, Collège National des Gynécologues Obstétriciens Français. Updated French guidelines for diagnosis and management of pelvic inflammatory disease. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2016 Aug:134(2):121-5. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.11.028. Epub 2016 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 27170602]

Jaiyeoba O, Lazenby G, Soper DE. Recommendations and rationale for the treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease. Expert review of anti-infective therapy. 2011 Jan:9(1):61-70. doi: 10.1586/eri.10.156. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21171878]

Mollen CJ, Pletcher JR, Bellah RD, Lavelle JM. Prevalence of tubo-ovarian abscess in adolescents diagnosed with pelvic inflammatory disease in a pediatric emergency department. Pediatric emergency care. 2006 Sep:22(9):621-5 [PubMed PMID: 16983244]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGoje O, Markwei M, Kollikonda S, Chavan M, Soper DE. Outcomes of Minimally Invasive Management of Tubo-ovarian Abscess: A Systematic Review. Journal of minimally invasive gynecology. 2021 Mar:28(3):556-564. doi: 10.1016/j.jmig.2020.09.014. Epub 2020 Sep 28 [PubMed PMID: 32992023]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceJiang X, Shi M, Sui M, Wang T, Yang H, Zhou H, Zhao K. Clinical value of early laparoscopic therapy in the management of tubo-ovarian or pelvic abscess. Experimental and therapeutic medicine. 2019 Aug:18(2):1115-1122. doi: 10.3892/etm.2019.7699. Epub 2019 Jun 21 [PubMed PMID: 31384333]

Expert Panel on Interventional Radiology, Weiss CR, Bailey CR, Hohenwalter EJ, Pinchot JW, Ahmed O, Braun AR, Cash BD, Gupta S, Kim CY, Knavel Koepsel EM, Scheidt MJ, Schramm K, Sella DM, Lorenz JM. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Radiologic Management of Infected Fluid Collections. Journal of the American College of Radiology : JACR. 2020 May:17(5S):S265-S280. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2020.01.034. Epub [PubMed PMID: 32370971]

Shigemi D, Matsui H, Fushimi K, Yasunaga H. Laparoscopic Compared With Open Surgery for Severe Pelvic Inflammatory Disease and Tubo-Ovarian Abscess. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019 Jun:133(6):1224-1230. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003259. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31135738]

Wallace MJ, Chin KW, Fletcher TB, Bakal CW, Cardella JF, Grassi CJ, Grizzard JD, Kaye AD, Kushner DC, Larson PA, Liebscher LA, Luers PR, Mauro MA, Kundu S, Society of Interventional Radiology (SIR). Quality improvement guidelines for percutaneous drainage/aspiration of abscess and fluid collections. Journal of vascular and interventional radiology : JVIR. 2010 Apr:21(4):431-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.12.398. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20346880]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence