Arteriovenous Malformation of the Brain

Arteriovenous Malformation of the Brain

Introduction

Arteriovenous malformations (AVMs) are a developmental anomaly of the vascular system, consisting of tangles of poorly formed blood vessels in which the feeding arteries are directly connected to a venous drainage network without any interposed capillary system.[1][2][3][4]

AVMs can occur anywhere in the body, however, brain AVMs are of special concern because of the inherent high risk of bleeding of the abnormal blood vessels that can cause neurological damage.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Not much is known about the etiology of brain AVMs. The cause of brain AVMs is yet unknown, however, it is possibly multifactorial; apparently both genetic mutation and angiogenic stimulation (the physiological process of formation of new blood vessels from pre-existing vessels) playing roles in AVM development. Some believe that AVMs develop in utero. While others advocate an angiopathic reaction, following either a cerebral ischemic or hemorrhagic event (subtypes of stroke) as a primary factor in their development.[5][6][7][8]

Epidemiology

The incidence in the United States is 1.34 per 100,000 person-years, although the actual prevalence rate is higher due to clinically silent disease, as only 12% of AVMs are estimated to become symptomatic. The mortality rate is 10-15% of patients who have a hemorrhage, and morbidity varies from approximately 30-50%. There is no sex predilection. Despite the considered congenital origin of AVMs, the clinical presentation most commonly occurs in young adults.

Pathophysiology

Arteriovenous malformations are composed of a central vascular nidus which is a conglomerate of arteries and veins. There is no intervening capillary bed, and the feeding arteries drain directly into the draining veins by one or multiple fistulae. These arteries lack the normal muscularis layer and the draining veins often appear dilated due to the shunted high-velocity arterial blood flow entering through the fistulae.

AVMs cause neurological dysfunction through the following three possible pathophysiological mechanisms. Firstly, the abnormal blood vessels have a propensity to bleed resulting in hemorrhage occurring in the subarachnoid space, the intraventricular space, or, more commonly in the brain parenchyma. Secondly, in the absence of hemorrhage, seizures may occur as a consequence of the mass effect of AVM or venous hypertension in draining veins. The third important cause of slowly progressive neurological deficits is attributed to the"steal phenomenon" which is thought to be related to normal brain parenchyma deprivation from nutrients and oxygen, as blood bypasses the normal capillary bed to the malformed arteriovenous channels.

History and Physical

AVMs tend to be clinically asymptomatic in 15% of cases until the presenting event occurs.

- Approximately 41 to 79 percent present with intracranial hemorrhage. AVMs are the second most common cause of intracranial bleed after cerebral aneurysms, responsible for 10 percent of all cases of subarachnoid hemorrhage. Children are more likely to present with hemorrhage than adults. Hemorrhages are usually intraparenchymal, but can primarily occur in the subarachnoid space. Symptoms due to hemorrhage include loss of consciousness, sudden and severe headache, nausea, vomiting as the coagulated blood makes its way down to be dissolved in the individual's spinal fluid. Reported sequelae caused by local brain tissue damage on the bleed site are also possible, including seizure, hemiparesis, a loss of touch sensation on one side of the body, and deficits in language processing. Minor bleeding may be asymptomatic. Following the arrest of bleeding, most AVM victims recover symptomatically, as the damaged blood vessel repairs itself.

-

Studies report seizure as a presenting disorder in 15 to 40% of patients. The risk of seizures increases with cortically-located, large, multiple, and superficial-draining AVMs. Seizures are typically focal, either simple or partial complex, but often show secondary generalization.

-

The progressive neurological deficit may occur in 6 to 12% of patients over a few months to several years. A vascular steal syndrome has been hypothesized to cause this presentation, but in most cases, this is related to mass effect, hemorrhage, or seizure. These include seizure, hemiparesis, visual disturbances, loss of sensation in one-half of the body, and aphasia. Minor bleeding can occur with no noticeable symptoms.

- A headache – There are no specific headache features that associate with AVM, which may be incidental to the headaches.

Evaluation

Brain AVMs are typically first identified in cross-sectional imaging - computed tomogram (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). A combination of MRI and angiography are often helpful to plan therapy and predicting the likely success and associated risks of surgical, endovascular, or radiological therapy.

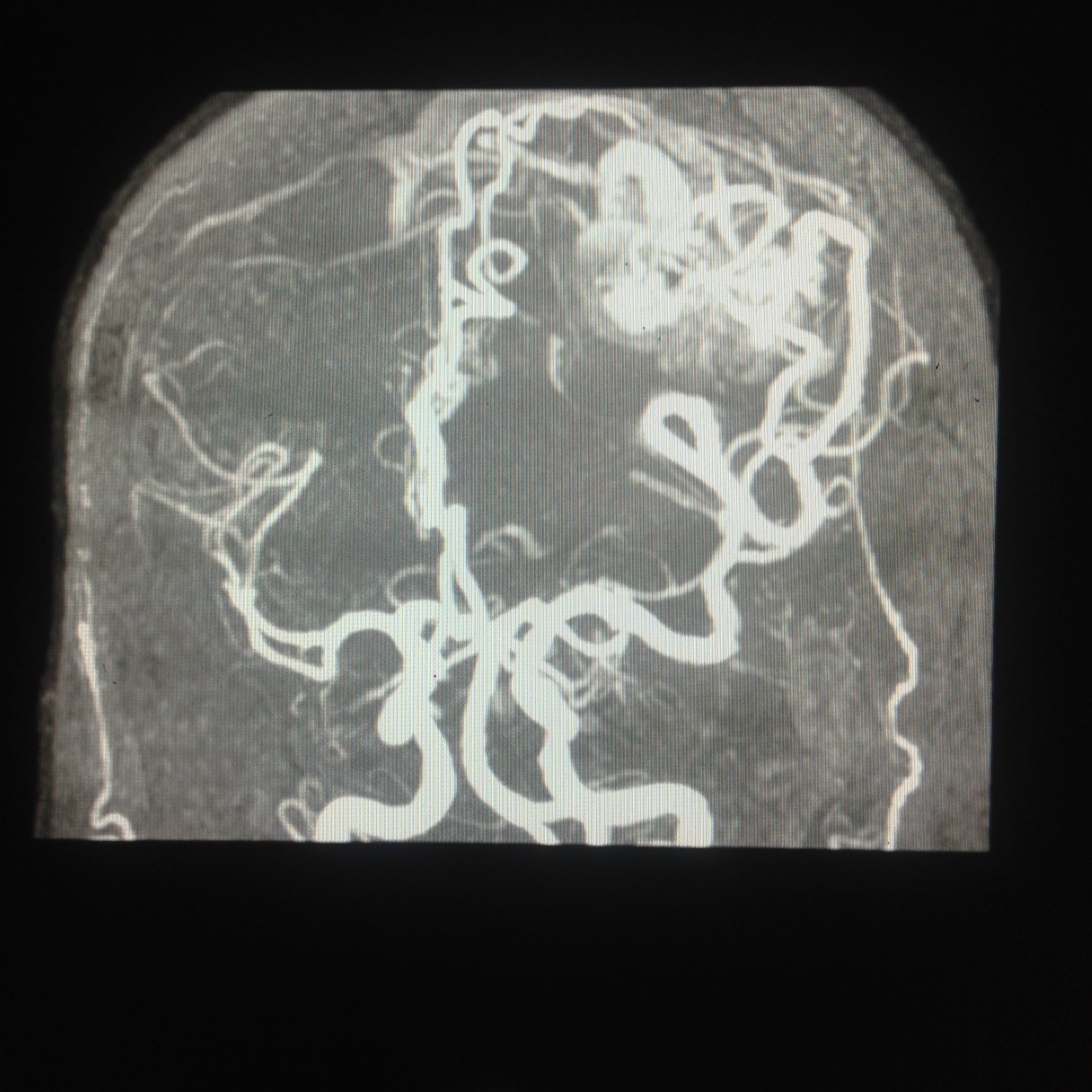

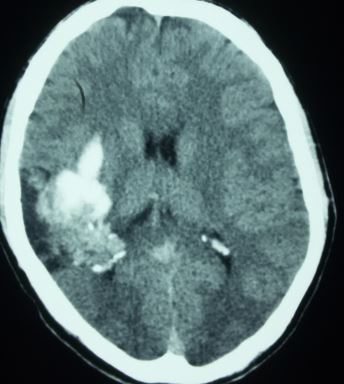

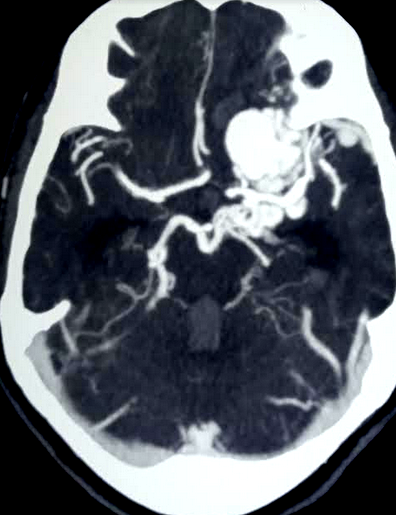

Computed tomography — On non-contrast CT the nidus is blood density and therefore usually somewhat hyperdense compared to adjacent brain, enlarged draining veins, and calcification may be evident. Although many of them are large, however, no mass effect or edema is present unless they bleed. On postcontrast CT especially with CT angiogram, the diagnosis is easily derived with visible feeding arteries, nidus, and draining veins apparent in the so-called "bag of worm" appearance. The exact anatomy of feeding vessels and draining veins can usually be delineated with angiography. The sensitivity of CT to identify brain AVMs in the acute setting of hemorrhage is reduced owing to compression of the nidus by the hematoma so more sensitive techniques such as MRI or angiography are required.

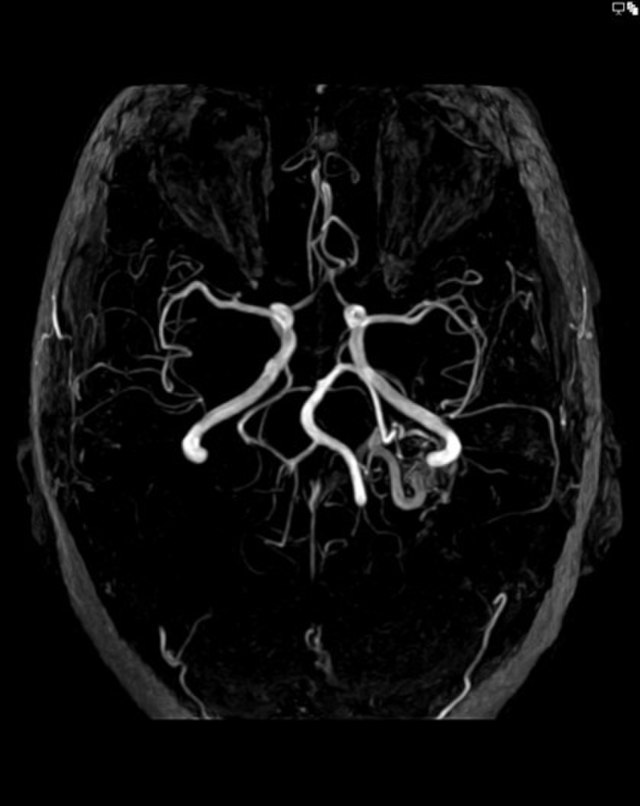

Magnetic resonance imaging — MRI is very sensitive for plotting the location of the brain AVM nidus and often an associated draining vein or any distant bleeding event. Fast flow in a conglomerate of tangled blood vessels generates serpiginous and tubular flow voids seen on bothT1 and T2, however mostly evident on T2 weighted images. Complications like the previous hemorrhage, adjacent brain edema, and atrophy may be seen.

After radiosurgery, MRI can evaluate the regression of the nidus volume, post-therapy edema as well as radiation necrosis in the radiation field.

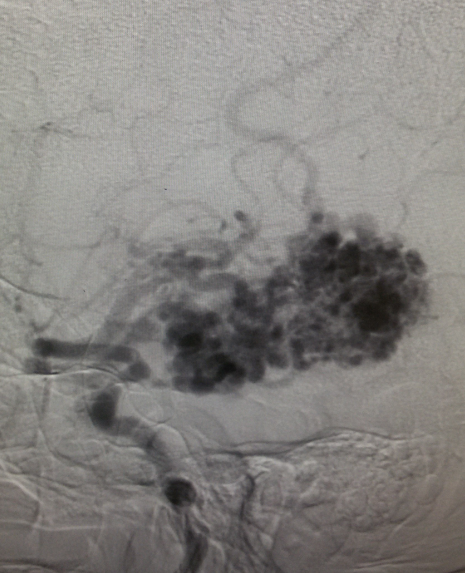

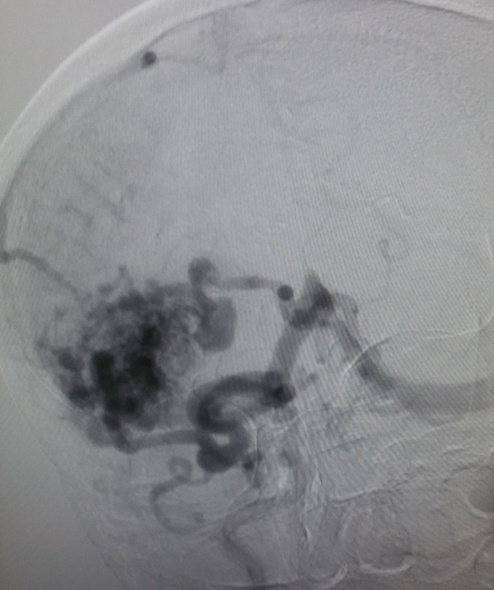

Angiography — It remains the gold standard for diagnosis and treatment planning. Nidus configuration, its relationship, and drainage to surrounding vessels are precisely evaluated. The presence of an associated aneurysm suggests a higher risk for hemorrhage. Contrast transit time, which relates to the flow state of the lesion, can provide critical information for endovascular treatment planning.

Treatment / Management

Treatment modalities —Invasive management is recommended for younger patients with the presence of one or more of the high-risk features for an AVM rupture, whereas in the case of older individuals with no high-risk features, the usual best treatment is medical management. In these particular patients, anticonvulsants for seizure control and pertinent analgesia for headaches may be the only management required. Several studies report that a history of the previous rupture is one of the most significant risk factors that predict long-term bleeding risk. Other important factors include patient age, AVM location, the presence of aneurysms, size, and other vascular features. Patients with AVMs and intractable epilepsy are also candidates for AVM treatment.[9][10][11][12][13](A1)

Surgical excision — Open microsurgical excision is the mainstay of treatment and offers the cure for patients considered to be at high risk of hemorrhage.

Spetzler-Martin Grade (SMG) scale is commonly employed for the assessment of the risk of surgical morbidity and mortality with brain AVMs. It is a composite score of nidus size (<3 cm, 3-6 cm, >6 cm; 1-3 points), the eloquence of adjacent brain (1 point for lesions located in the brainstem, cerebellar peduncles, thalamus, hypothalamus, or language, sensorimotor, or primary visual cortex), and venous drainage (1 point if any or all of venous drainage is via deep veins, such as basal veins, internal cerebral veins, or precentral cerebellar veins). The higher the score, the higher the associated surgical morbidity and mortality risk.

Radiotherapy and endovascular embolization are not only useful alternatives to surgical treatment in patients at high risk for surgical therapy but can also be useful adjuncts to the main surgical management.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of cerebral AVMs include:

- Carotid/vertebral artery dissection

- Cavernous sinus syndromes and thrombosis

- Cerebral amyloid angiopathy

- Cerebral venous thrombosis

- Dissection syndromes

- Fibromuscular dysplasia

- Intracranial aneurysms

- Migraine and cluster headaches

- Moyamoya disease

- Stroke

- Vein of Galen malformation

Prognosis

There are different scoring systems in order to identify the morbidity and mortality associated with observation vs intervention in different types of cerebral AVMs. The main ones are:

- Spetzler-Martin scale - for microsurgery

- Supplementary Spetzler-Martin scale - for microsurgery

- Pittsburgh radiosurgery-based AVM grading scale

- Toronto score - for microsurgery

- Buffalo Score - for endovascular treatment

Complications

The main complications associated with AVMs include:

- Intracranial bleed

- Mass effect

- Seizures

- Steal phenomenon

- Neurological deficits

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patient should be properly educated regarding the chance of intracerebral bleed and seizures if the lesion is being conservatively managed. Also, the fitness to drive should be sorted out.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The diagnosis and management of brain AVM are with an interprofessional team that consists of a neurosurgeon, neurologist, internist, and an invasive radiologist. The follow-up of these patients is usually by the nurse practitioner and primary care provider. The management of brain AVMs depends on the size, location, patient age, and status of the AVM (high risk of rupture). While surgery is the mainstay treatment, embolization is another option. The outcomes of these patients depend on the AVM size, presence of symptoms, location, patient comorbidity, and mental status. Complications following surgery are common and recovery in many patients is prolonged requiring extensive rehab. The most significant risk factor for death is the rupture of the AVM.[2][9][14] (Level V)

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Claro E, Dias A, Girithari G, Massano A, Duarte MA. Non-traumatic Hematomyelia: A Rare Finding in Clinical Practice. European journal of case reports in internal medicine. 2018:5(11):000961. doi: 10.12890/2018_000961. Epub 2018 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 30755987]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWu EM, El Ahmadieh TY, McDougall CM, Aoun SG, Mehta N, Neeley OJ, Plitt A, Shen Ban V, Sillero R, White JA, Batjer HH, Welch BG. Embolization of brain arteriovenous malformations with intent to cure: a systematic review. Journal of neurosurgery. 2019 Feb 1:132(2):388-399. doi: 10.3171/2018.10.JNS181791. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30717053]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceXu H, Wang L, Guan S, Li D, Quan T. Embolization of brain arteriovenous malformations with the diluted Onyx technique: initial experience. Neuroradiology. 2019 Apr:61(4):471-478. doi: 10.1007/s00234-019-02176-2. Epub 2019 Feb 2 [PubMed PMID: 30712140]

Heit JJ, Thakur NH, Iv M, Fischbein NJ, Wintermark M, Dodd RL, Steinberg GK, Chang SD, Kapadia KB, Zaharchuk G. Arterial-spin labeling MRI identifies residual cerebral arteriovenous malformation following stereotactic radiosurgery treatment. Journal of neuroradiology = Journal de neuroradiologie. 2020 Feb:47(1):13-19. doi: 10.1016/j.neurad.2018.12.004. Epub 2019 Jan 15 [PubMed PMID: 30658138]

Li W, Sun Q, Duan X, Yi F, Zhou Y, Hu Y, Yao L, Xu H, Zhou L. [Etiologies and risk factors for young people with intracerebral hemorrhage]. Zhong nan da xue xue bao. Yi xue ban = Journal of Central South University. Medical sciences. 2018 Nov 28:43(11):1246-1250. doi: 10.11817/j.issn.1672-7347.2018.11.013. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30643071]

Caranfa JT, Baldwin MT, Rutter CE, Bulsara KR. Synchronous cerebral arteriovenous malformation and lung adenocarcinoma carcinoma brain metastases: A case study and literature review. Neuro-Chirurgie. 2019 Feb:65(1):36-39. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2018.07.003. Epub 2019 Jan 9 [PubMed PMID: 30638546]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKhandelwal A, Chaturvedi A, Singh GP, Mishra RK. Intractable brain swelling during cerebral arteriovenous malformation surgery due to contralateral acute subdural haematoma. Indian journal of anaesthesia. 2018 Dec:62(12):984-987. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_491_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30636801]

Hofman M, Jamróz T, Kołodziej I, Jaskólski J, Ignatowicz A, Jakutowicz I, Przybyłko N, Kocur D, Baron J. Cerebral arteriovenous malformations - usability of Spetzler-Martin and Spetzler-Ponce scales in qualification to endovascular embolisation and neurosurgical procedure. Polish journal of radiology. 2018:83():e243-e247. doi: 10.5114/pjr.2018.76750. Epub 2018 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 30627242]

Kocer N, Kandemirli SG, Dashti R, Kizilkilic O, Hanimoglu H, Sanus GZ, Tunali Y, Tureci E, Islak C, Kaynar MY. Single-stage planning for total cure of grade III-V brain arteriovenous malformations by embolization alone or in combination with microsurgical resection. Neuroradiology. 2019 Feb:61(2):195-205. doi: 10.1007/s00234-018-2140-z. Epub 2018 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 30488257]

Ironside N, Chen CJ, Ding D, Ilyas A, Kumar JS, Buell TJ, Taylor D, Lee CC, Sheehan JP. Seizure Outcomes After Radiosurgery for Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformations: An Updated Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. World neurosurgery. 2018 Dec:120():550-562.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.08.121. Epub 2018 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 30149174]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMosimann PJ, Chapot R. Contemporary endovascular techniques for the curative treatment of cerebral arteriovenous malformations and review of neurointerventional outcomes. Journal of neurosurgical sciences. 2018 Aug:62(4):505-513. doi: 10.23736/S0390-5616.18.04421-1. Epub 2018 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 29582979]

Shovlin CL, Condliffe R, Donaldson JW, Kiely DG, Wort SJ, British Thoracic Society. British Thoracic Society Clinical Statement on Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations. Thorax. 2017 Dec:72(12):1154-1163. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210764. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29141890]

Cenzato M, Boccardi E, Beghi E, Vajkoczy P, Szikora I, Motti E, Regli L, Raabe A, Eliava S, Gruber A, Meling TR, Niemela M, Pasqualin A, Golanov A, Karlsson B, Kemeny A, Liscak R, Lippitz B, Radatz M, La Camera A, Chapot R, Islak C, Spelle L, Debernardi A, Agostoni E, Revay M, Morgan MK. European consensus conference on unruptured brain AVMs treatment (Supported by EANS, ESMINT, EGKS, and SINCH). Acta neurochirurgica. 2017 Jun:159(6):1059-1064. doi: 10.1007/s00701-017-3154-8. Epub 2017 Apr 7 [PubMed PMID: 28389875]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencevan Essen MJ, Han KS, Lo RTH, Woerdeman P, van der Zwan A, van Doormaal TPC. Functional and educational outcomes after treatment for intracranial arteriovenous malformations in children. Acta neurochirurgica. 2018 Nov:160(11):2199-2205. doi: 10.1007/s00701-018-3665-y. Epub 2018 Sep 7 [PubMed PMID: 30191363]