Diagnostic Ultrasound Use in Undifferentiated Hypotension

Diagnostic Ultrasound Use in Undifferentiated Hypotension

Introduction

Hypotension is a common presentation in the emergency department.[1] At times, the available history is limited, and the physical exam alone may be misleading.[2][3] In these life-threatening situations, waiting for laboratory studies or formal imaging studies may not be feasible. Instead, using bedside ultrasound can quickly narrow the potential etiologies of the hypotension.[4] Multiple ultrasound protocols have been proposed for the evaluation of the hypotensive patient. The commonly-used rapid ultrasound in shock (RUSH) exam will be reviewed here. This bedside protocol has been demonstrated to quickly and accurately determine the etiology of shock in the hands of an emergency medicine physician.[5]

The HI-MAP mnemonic describes the components of the RUSH protocol: heart, inferior vena cava (IVC), Morrison’s pouch (focused assessment with sonography for trauma [FAST] views with thoracic windows), aorta, pulmonary. This allows for a systematic approach to the exam.[5] Others have also simplified the exam into the “pump, tanks, pipes” approach.

Technique or Treatment

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Technique or Treatment

The RUSH Exam

Heart: At least two views of the heart should be obtained to answer 3 important clinical questions.

- First, how well is the heart pumping? This question can be answered by obtaining a parasternal long-axis view to assess the volume change and general activity of the left ventricle from systole to diastole. From here, various methods may be used to estimate cardiac function. This includes quantitative assessments such as fractional shortening (using M-mode to quantify left ventricular excursion from systole to diastole) or E-point septal separation (again using M-mode, but this time to quantify movement of the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve. In an otherwise normal heart with an appropriate ejection fraction, this portion of the valve should almost hit the interventricular septum). Alternatively, cardiac function may be qualitatively assessed; as mentioned, the anterior leaflet of the mitral valve should almost hit the interventricular septum, and the left ventricular chamber size should decrease by approximately 40% in systole. If, instead, the heart is noted to be “hyperdynamic” or almost collapsing completely with each contraction, suspect a distributive etiology such as sepsis. If the heart is hardly moving and appears dilated, suspect a cardiogenic etiology of shock.

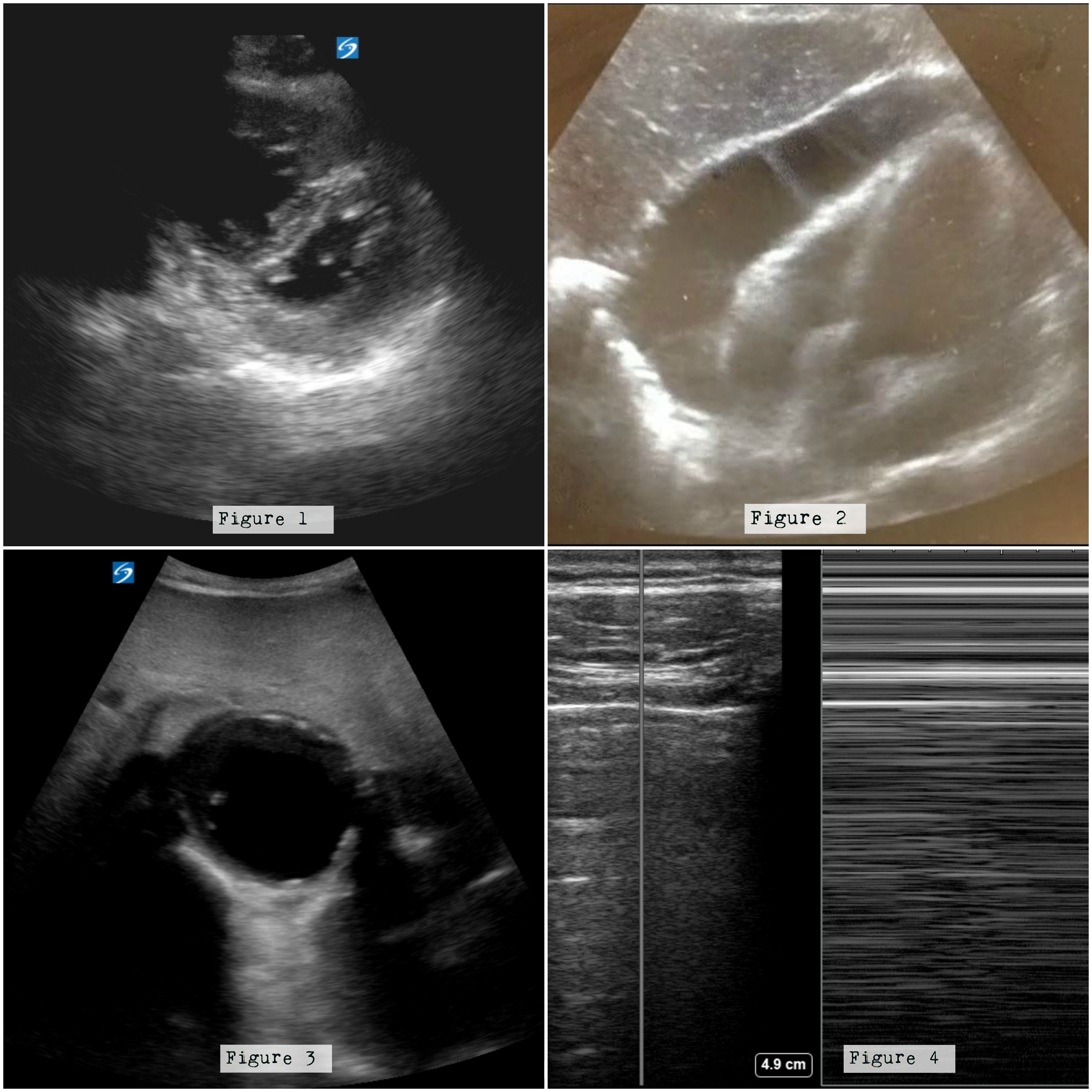

- Second, is there evidence of right ventricular strain suggestive of a pulmonary embolus? This question can be answered while in the parasternal long-axis (PLAX) view by assessing the size of the right ventricle (which should approximately equate to the size of the aortic outflow tract and left atrium in this view); however, if obtained, additional views may increase the accuracy of this diagnosis. Normally, at the end of diastole, the right and left ventricles should have a ratio of 0.6:1.[6] If this ratio is exceeded, particularly greater than 1:1 in the setting of a thin right ventricular (RV) wall, suspect acute RV strain secondary to a pulmonary embolus in the appropriate clinical setting. Additionally, RV enlargement with bowing of the septum into the left ventricle on a parasternal short-axis view in combination with RV enlargement is highly suspicious for RV strain (Figure 1).[7]

- Finally, is there evidence of a clinically significant pericardial effusion? This can be answered in a subxiphoid view. In this view, pericardial effusion can be seen as a dark or anechoic area inside the bright or hyperechoic stripe of the pericardium (Figure 2). In this view, the near-field or area closest to the probe reflects the most dependent area and, thus, the area where fluid should layer first. As the effusion increases in size, it will typically layer out around the heart inside the pericardium and can be seen in the far-field as well. If an effusion is acute, it may only take a small amount of fluid to cause hemodynamic compromise, while a chronic effusion may slowly increase in size such that a larger volume can accumulate before there are any significant adverse effects on cardiac output. Findings suggestive of tamponade include right atrial or right ventricular collapse during diastole.[8]

Inferior Vena Cava: Views of the IVC can be obtained from a subxiphoid/subcostal position and allow for rapid assessment of the volume status of a hypotensive patient. Specifically, the IVC can be assessed for how distended or collapsible it is with respirations to obtain an idea of the volume tolerance of a spontaneously breathing patient. Note that the IVC will decrease in size in spontaneously breathing patients secondary to generated negative intrathoracic pressures and enlarge on expiration, while the reverse is true in mechanically ventilated patients.It is important to note the previously established difference between fluid tolerance (can this patient tolerate more fluids, or will additional hydration result in adverse effects such as pulmonary edema) and fluid responsiveness (will this patient increase their cardiac output in response to more fluids?).[9] It has been demonstrated previously that measuring IVC distensibility throughout the respiratory cycle accurately predicted fluid responsiveness (a more useful measure) in mechanically ventilated patients.[10] It was initially believed that IVC collapse in a spontaneously breathing patient was a more accurate indicator of simple fluid tolerance, but recent studies have demonstrated a relationship between collapsibility and fluid responsiveness as well.[11]While these quantitative measurements can be obtained, simple qualitative visual assessments can be helpful as well. If the IVC is noted to be almost completely collapsible with respirations in a spontaneously breathing patient, it is likely that the patient is in a distributive or hemorrhagic state of shock (depending on the clinical scenario) and will not only be fluid tolerant but fluid responsive as well. If the IVC is noted to be plump with limited respiratory phasic variation, the patient is likely at the limits of their volume tolerance and responsiveness. The addition of a bedside echocardiogram consistent with a poorly contractile heart and hemodynamic instability would support the diagnosis of cardiogenic shock.

Morrison’s pouch: The “M” in the HI-MAP mnemonic presented above is meant to represent not only the “Morrison’s pouch” view but also the remainder of the FAST (focused assessment with sonography in trauma) exam. The sonographer searches for any evidence of dark or anechoic free fluid that would be suggestive of intraperitoneal hemorrhage. In the RUSH exam, the traditional right upper quadrant and left upper quadrant views are adjusted by moving the probe superiorly also to include thoracic views examining for fluid above the diaphragm suggestive of a pleural effusion or a hemothorax depending on the clinical situation.

Aorta: Ultrasonographic views of the abdominal aorta can be quickly obtained by starting in the upper abdomen to view the proximal portion of the abdominal aorta and moving distally to view the mid-abdominal aorta until it bifurcates into the iliac vessels at approximately the level of the umbilicus. Any measurement of the aortic diameter (measured from outer lumen to outer lumen in an anterior to posterior fashion) greater than or equal to 3 cm should raise suspicion for a ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm as an etiology of the patient’s hypotension (Figure 3).[12]

Pulmonary: Lung ultrasound can be quickly performed to assess for pneumothorax as well as B lines suggestive of interstitial edema. During image acquisition, the probe is placed on the chest wall in a rib interspace; the parietal and visceral pleura can be noted to be sliding against each other during normal respiration. Alternatively, M-mode can be used to generate a visual graph with the classical appearance of the “seashore sign” in the healthy lung. The absence of lung sliding and the visualization of the “barcode sign” in a hypotensive patient should prompt consideration of tension pneumothorax as a potential cause of hypotension (Figure 4).

During visualization of the lungs, the sonographer may notice B lines (vertical comet-like projections that start at the pleural line and move with respiration) which are suggestive of pulmonary congestion.[13] If three or more B lines are present in multiple lung zones, this suggests clinically significant pulmonary fluid overload.[14] In the right setting and the company of other ultrasound findings as discussed above, this suggests a patient who is at the limits of his or her volume tolerance and/or may raise the suspicion for a cardiogenic etiology of hypotension.

Clinical Significance

The RUSH exam is a useful, validated clinical tool that can be used rapidly at the bedside to help establish the etiology of an otherwise undifferentiated patient’s hypotension. Multiple resources are available to guide learners through the examination details, for example, probe selection, sequencing, and interpretation of the acquired images. This article is provided as a brief review of the RUSH exam and how to utilize the protocol at the bedside to differentiate the various causes of hypotension in a crashing patient and allowing the clinician to provide life-saving interventions.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of undifferentiated hypotension is best done with an interprofessional team including clinicians, specialists, ICU nurses, and ultrasound technicians. The RUSH exam can be performed at the bedside and may provide a clue to the diagnosis. The imaging modality helps avoid transporting an unstable patient to an unmonitored radiology unit. Prompt diagnostic evaluation and interpretation by the interprofessional healthcare team will result in improved intervention and patient outcomes. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Figure 1: Note the enlarged right ventricle displacing the septum into the left ventricle. Figure 2: There is a large effusion surrounding the four chambers of the heart. Figure 3: Note the enlarged aorta. Figure 4: Note the barcode sign on the right when M mode is used between a rib interspace. Images courtesy of Damali Nakitende, MD, and Katharine Burns, MD, of Advocate Christ Medical Center.

References

Holler JG, Henriksen DP, Mikkelsen S, Pedersen C, Lassen AT. Increasing incidence of hypotension in the emergency department; a 12 year population-based cohort study. Scandinavian journal of trauma, resuscitation and emergency medicine. 2016 Mar 2:24():20. doi: 10.1186/s13049-016-0209-4. Epub 2016 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 26936190]

McGee S, Abernethy WB 3rd, Simel DL. The rational clinical examination. Is this patient hypovolemic? JAMA. 1999 Mar 17:281(11):1022-9 [PubMed PMID: 10086438]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWo CC, Shoemaker WC, Appel PL, Bishop MH, Kram HB, Hardin E. Unreliability of blood pressure and heart rate to evaluate cardiac output in emergency resuscitation and critical illness. Critical care medicine. 1993 Feb:21(2):218-23 [PubMed PMID: 8428472]

Jones AE, Tayal VS, Sullivan DM, Kline JA. Randomized, controlled trial of immediate versus delayed goal-directed ultrasound to identify the cause of nontraumatic hypotension in emergency department patients. Critical care medicine. 2004 Aug:32(8):1703-8 [PubMed PMID: 15286547]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBagheri-Hariri S, Yekesadat M, Farahmand S, Arbab M, Sedaghat M, Shahlafar N, Takzare A, Seyedhossieni-Davarani S, Nejati A. The impact of using RUSH protocol for diagnosing the type of unknown shock in the emergency department. Emergency radiology. 2015 Oct:22(5):517-20. doi: 10.1007/s10140-015-1311-z. Epub 2015 Mar 21 [PubMed PMID: 25794785]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGoldhaber SZ. Echocardiography in the management of pulmonary embolism. Annals of internal medicine. 2002 May 7:136(9):691-700 [PubMed PMID: 11992305]

Vieillard-Baron A, Page B, Augarde R, Prin S, Qanadli S, Beauchet A, Dubourg O, Jardin F. Acute cor pulmonale in massive pulmonary embolism: incidence, echocardiographic pattern, clinical implications and recovery rate. Intensive care medicine. 2001 Sep:27(9):1481-6 [PubMed PMID: 11685341]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGoodman A, Perera P, Mailhot T, Mandavia D. The role of bedside ultrasound in the diagnosis of pericardial effusion and cardiac tamponade. Journal of emergencies, trauma, and shock. 2012 Jan:5(1):72-5. doi: 10.4103/0974-2700.93118. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22416160]

Mackenzie DC, Noble VE. Assessing volume status and fluid responsiveness in the emergency department. Clinical and experimental emergency medicine. 2014 Dec:1(2):67-77 [PubMed PMID: 27752556]

Bendjelid K, Romand JA. Fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients: a review of indices used in intensive care. Intensive care medicine. 2003 Mar:29(3):352-60 [PubMed PMID: 12536268]

Lanspa MJ, Grissom CK, Hirshberg EL, Jones JP, Brown SM. Applying dynamic parameters to predict hemodynamic response to volume expansion in spontaneously breathing patients with septic shock. Shock (Augusta, Ga.). 2013 Feb:39(2):155-60. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e31827f1c6a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23324885]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRubano E, Mehta N, Caputo W, Paladino L, Sinert R. Systematic review: emergency department bedside ultrasonography for diagnosing suspected abdominal aortic aneurysm. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2013 Feb:20(2):128-38. doi: 10.1111/acem.12080. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23406071]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLichtenstein D, Mézière G, Biderman P, Gepner A, Barré O. The comet-tail artifact. An ultrasound sign of alveolar-interstitial syndrome. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1997 Nov:156(5):1640-6 [PubMed PMID: 9372688]

Volpicelli G, Elbarbary M, Blaivas M, Lichtenstein DA, Mathis G, Kirkpatrick AW, Melniker L, Gargani L, Noble VE, Via G, Dean A, Tsung JW, Soldati G, Copetti R, Bouhemad B, Reissig A, Agricola E, Rouby JJ, Arbelot C, Liteplo A, Sargsyan A, Silva F, Hoppmann R, Breitkreutz R, Seibel A, Neri L, Storti E, Petrovic T, International Liaison Committee on Lung Ultrasound (ILC-LUS) for International Consensus Conference on Lung Ultrasound (ICC-LUS). International evidence-based recommendations for point-of-care lung ultrasound. Intensive care medicine. 2012 Apr:38(4):577-91. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2513-4. Epub 2012 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 22392031]