Introduction

Vocal fold immobility is a broad term referring to the abnormal movement of the true vocal folds. The abnormal movement can arise from reduced mobility (paretic) or complete cessation of any vocal fold movement (paralytic). The condition can be unilateral or bilateral. Unilateral vocal fold paralysis (UVFP) is more common than the bilateral type.

Vocal Fold Anatomy

The vagus nerve innervates the larynx and its associated muscles. Vagal nerve fibers arise from the nucleus ambiguus in the brainstem medulla. Upper-motor corticobulbar neurons descend from the cerebral cortex to the nucleus ambiguus, stimulating these vagal nerve fibers. The fibers coalesce and exit the brainstem via the jugular foramen as the 10th cranial nerve.

The vagus nerve then descends inferior to the skull base, passes into the neck, and gives off 3 main branches: the pharyngeal branch, superior laryngeal nerve (SLN), and recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN). The SLN is responsible for laryngeal sensation in the superior glottic aspect and cricothyroid muscle motion.

The RLN classically descends further into the neck and thorax, loops around the subclavian artery on the right and aortic arch on the left, and ascends back into the neck in the tracheoesophageal groove. The RLN then enters the larynx posteriorly, near the cricothyroid joint. However, a small proportion of the population has a "nonrecurrent laryngeal nerve" that directly innervates the larynx without passing the thorax.[1]

The RLN provides sensation to the glottis and subglottis and motor innervation to all remaining intrinsic laryngeal muscles, including the posterior cricoarytenoid, interarytenoid, lateral cricoarytenoid, and thyroarytenoid muscles.[2][3][4][5] The cause of unilateral vocal fold paralysis can arise in the larynx and anywhere along the RLN pathway. The role of SLN injury in UVFP pathophysiology is insignificant.[73]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

UVFP etiology varies with geography and time. Data obtained from 1985 through 1995 in a large North American case series showed cancer to be the most common cause of UVFP.[6] However, increasing head and neck surgery also increased the prevalence of UVFP arising from iatrogenic surgical injury (37%) from 1996 through 2005. Nonthyroid procedures (66%) surpassed thyroidectomy (33%) as the most common mode of injury. By contrast, a large Italian study showed that thyroidectomy (41.3%), idiopathic paralysis (25.3%), and thoracic surgery (12.1%) were the chief UVFP causative factors.[7]

Malignancy is the most worrisome cause of UVFP and is most commonly seen in primary and metastatic lung and laryngeal carcinoma. Thyroid and central nervous system (CNS) cancers are less frequently seen.[8] A 1991 Stanford University study reported that out of 1,019 UVFP cases from 1970 to 1991, neoplasm (35.5%) was the most common etiology, 54.8% of which had a lung primary.[9]

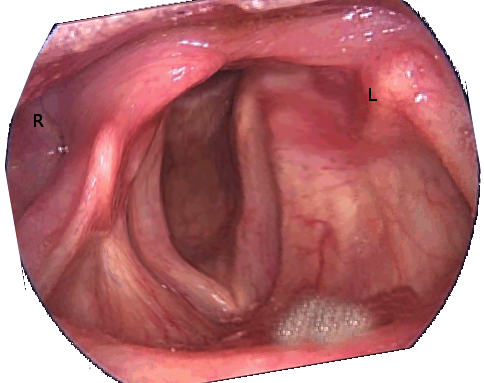

Iatrogenic injury has traditionally been attributed to thyroid surgery (see Image. Unilateral Vocal Cord Paralysis After a Left Parathyroidectomy). Aberrant recurrent laryngeal nerve anatomy, thyroid malignancy, and revision surgery increase the likelihood of postsurgical UVFP.[10][11][12][13] Intraoperative nerve stimulators are frequently used to avoid injury. The effectiveness of these devices has not been clinically proven, though continuous nerve monitoring has been associated with lower paresis and paralysis rates compared to intermittent nerve stimulation.[14][15][16][15]

Other surgeries with a significant recurrent laryngeal nerve risk include anterior cervical spine surgery, esophagectomy, and cardiothoracic surgery. However, any procedure requiring endotracheal tube (ETT) insertion may cause paralysis, either via pressure from the ETT or mechanical trauma to the arytenoids.[17]

Central causes, such as previous cerebral vascular accidents, brain stem or high skull-base tumors, and peripheral neurologic etiologies, must be entertained in the differential of a new-onset UVFP. A detailed neurologic examination is indicated in patients suspected to have UVFP of neurologic origin. New, isolated, neurologically related UVFP is rare, accounting for less than 5% of cases. One study following idiopathic UVFP over time demonstrated that up to 20% of these patients were subsequently diagnosed with a primary neurologic disorder.[18][19]

Mechanical causes, such as cricoarytenoid joint dislocation, must be considered, especially in the setting of recent laryngeal trauma or intubation. A history of blunt or penetrating neck trauma should strongly suggest this event as the cause. Meanwhile, the UVFP occurrence rate after routine intubation is extremely low, often quoted as 0.1% or less.[20]

Idiopathic UVFP, which some postulate as a postviral syndrome, is a common cause of UVFP but is a diagnosis of exclusion. The entire course of the vagus nerve, or RLN, must be examined to rule out more sinister pathologies before labeling the condition idiopathic. Overall, 29 to 67% of UVFP cases are classified as idiopathic, comprising the 2nd or 3rd largest etiologic category.[21]

Epidemiology

An American study examined the incidence of idiopathic UVFP over 7 years and described an overall prevalence of 1.04 cases per 100,000 persons per year[22]. Meanwhile, another study found that UVFP of a neurologic origin did not significantly differ in age, gender, or duration of symptoms from UVFP of a nonneurologic origin. However, previous cancer or thyroid disease history was significantly more common in the neurogenic group.[23]

Preoperative UVFP incidence in patients undergoing thyroid surgery has been documented as 1.3%. About 76% of individuals with preoperative UVFP were ultimately diagnosed with a thyroid malignancy.[24][25] UVFP is not pathognomonic for thyroid malignancy but is a worrisome sign. The incidence of UVFP after thyroid surgery ranges from 0.5 to 9.5%[26][27][28][27].

UVFP was reported in 1.2% of patients who underwent surgery for a primary lung malignancy, 0% to 59% of patients who underwent surgery for an esophageal malignancy, and 25% of patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery.[29][30][31] The incidence of UVFP after cervical spine surgery ranges from 2.3% to 24.2%.[32]

UVFP incidence after nonsurgical neck trauma is not well described and remains in the realm of case reports.[33] Neck trauma, particularly blunt neck trauma, is more often associated with bilateral vocal fold paralysis.[34][35]

Pathophysiology

Any lesion, inflammation, or trauma along the RLN's course can cause vocal cord movement alteration and dysphonia. UVFP can also arise from vocal fold or laryngeal injury. Intubation trauma is the most frequent reason for these injuries, though intubation-related UVFP is exceedingly rare, occurring in less than 1% of these procedures.[36] Arytenoid joint dislocation is the most common mechanism, potentially surgically correctable if identified in a timely fashion[37].

CNS pathologies such as stroke, tumors, high spinal lesions, and multiple sclerosis can also lead to vocal fold paresis and paralysis. Dysfunction severity and final vocal fold position typically depend on the neurologic lesion's site.[38]

History and Physical

Hoarseness is the most common presenting complaint of UVFP.[39] Symptoms that may also be reported include coughing, choking, aspiration, dyspnea, dysphagia, and globus sensation.

Dysphonia severity may relate to the paralyzed vocal fold's position. Laterally, patients often complain of a breathy voice and a poor or "bovine" cough due to air escaping through an abnormal glottal gap.[40][41] The gap forms as the paralyzed vocal fold cannot completely appose with the contralateral, nonparalyzed, vocal fold. Meanwhile, medial or paramedian lesions usually result in less severe dysphonia, and sensory symptoms may only be observed intermittently.[42]

Dysphagia is another common complaint due to the inability to close the glottis completely, thus impairing swallowing.[43] Severe dysphagia may lead to loss of airway protection, recurrent aspiration, and pneumonia.

Symptom onset, progression signs, accompanying neurologic changes, and antecedent trauma or infections are pertinent. Neoplastic, cardiovascular, or neurologic disease may be elicited in one's personal and family history. Chronic smoking, drinking, and carcinogenic exposures at home or work may be clues to a potentially malignant etiology.

A comprehensive physical exam should include a thorough head and neck examination to identify potential malignant sites. Thoracic pathology may damage the RLN as it descends at the level of the great blood vessels, so a complete inspection of this region is also vital.[44] A detailed neurologic examination may also help localize the lesion.[45] Patchy neurologic deficits may be indicative of multiple sclerosis.[46]

The vocal folds should be visualized either via mirror examination or flexible laryngoscopy. Stroboscopy can be a very useful adjunct. The vocal fold must be examined for residual movement in the paretic or paralytic fold, which can have prognostic and etiologic significance. Incomplete paralysis may suggest an evolving pathology, such as inflammation or infection, or recovery from one.[47] The paralytic fold's relative position—lateral or medial—should be noted to identify the potential pathology site and tailor the remainder of the workup.[48]

Evaluation

Patients presenting with UVFP immediately following thyroid or other neck surgery often do not require further formal workup. However, the operating surgeon must ascertain whether the nerve was physically intact at the end of the surgery. On the other hand, investigations of UVFP of unknown etiology should start with imaging of the RLN throughout its course from the skull base to the neck and chest. Both computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging can provide adequate information, though the choice should be based on clinical presentation and physician preference. Evidence of cranial nerve involvement, especially if concerning for a high-vagal injury like the presence of palatal weakness, necessitates CNS and skull-base imaging.[49][50][51][52]

Laryngeal electromyography (LEMG) may specifically rule out cricoarytenoid (CA) joint dislocation as a cause of UVFP. CA joint dislocation would present with normal LEMG findings, indicating that neuromuscular function is intact.[53] LEMG is more commonly utilized for monitoring paralytic vocal fold recovery or response to laryngeal reinnervation procedures[54]. This modality is most useful at 1 to 6 months following the injury or onset of paralysis.

LEMG findings may include the following:

- Normal motor unit potentials, indicating an intact neuromuscular junction

- Fibrillation potentials, indicating denervation injury to the muscle

- Polyphasic action potentials, signifying muscle reinnervation

These findings may be useful to help direct treatment options, depending on the clinical scenario.[55]

Treatment / Management

UVFP management should focus on removing the identified cause, preventing aspiration, and improving dysphonia. Treatment decisions must be tailored to each clinical scenario.

Idiopathic UVFP and its prognosis deserve special mention. Although not well-defined in the literature, this condition is believed to be secondary to a postviral or postinfectious insult, as happens in postviral facial paralysis and sensorineural hearing loss.

Sulica reported in 2008 that individuals who develop idiopathic UVFP do not completely recover vocal cord mobility at the same time, though vocal therapy can promote dysphonia resolution before full recovery. Most of these patients should recover fully a year after symptom onset.[56]

If the diagnostic workup does not find aspiration or any ominous pathology, a 12-month observation period and a speech therapy referral are recommended to see if the patient can regain vocal fold motion without aggressive intervention. Speech therapy can help patients recover vocal and swallowing functions and may negate the need for surgery even if complete vocal fold motion recovery does not occur[57].

Surgical interventions include temporary or permanent vocal fold augmentation, formal thyroplasty (medialization laryngoplasty), and arytenoid adduction. Vocal fold augmentation repositions the paralyzed vocal fold closer to the midline. Thus, the contralateral, fully functional true vocal fold can close the glottis during deglutition and phonation, helping prevent aspiration and improve dysphonia.

On the other hand, patients with UVFP and aspiration require a more aggressive approach, such as immediate injection augmentation, to protect the airway and prevent pneumonia. This procedure may still help patients without aspiration but are symptomatically dysphonic, as temporary injection augmentation can improve the voice. Hyaluronic acid is the preferred injectable agent if spontaneous recovery is expected.[58]

Permanent augmentation is indicated for patients with UVFP longer than 12 months. Permanent vocal-fold-augmentation options include formal thyroplasty and serial injections with longer-acting injectable materials, such as autologous fat.[59]

Teflon was a widely used injectable vocal-fold-augmenting agent in the past. However, this material is rarely used today, given the potential for morbidity from Teflon granuloma.[60] Historically, gel foam has also been used, though it lasts only 4 to 6 weeks.[61] By comparison, acellular dermal matrix (AlloDerm, Cymetra) can last 2 to 4 months. However, potential risks include intralaryngeal abscess and, if injected into Rienke's space, micronodule formation.[61] Calcium hydroxyapatite can last 18 months and has comparable safety and efficacy to hyaluronic acid.(B2)

Hyaluronic acid is the most widely studied injectable vocal-fold-augmenting material available in various brands. This material's viscosity is similar to that of natural mucosa and thus interferes less with the mucosal wave. Low-viscosity preparations are injected submucosally or into Rienke's space, while high-viscosity preparations can be injected intramuscularly.[62] Reported duration is variable but averages 4 to 12 months, depending on the brand or formulation used.[63](B2)

Potentially permanent injectable materials include autologous fat and fascia. Both are advantageous in that they are completely autologous, living material. The long-term outcomes, however, have been extremely variable in terms of duration and phonatory results. For example, autologous fat has nearly the same viscoelastic properties as the native mucosa. However, fat's survival and duration of benefit are extremely variable. Thus, this option has fallen from favor in many centers.[64] Meanwhile, fascia can last years but is less widely used. Donor site morbidity remains a concern, and fascia has been described as less suitable for correcting wide glottic gaps.[65]

Injection augmentation can be performed under general anesthesia in a hospital setting with direct vocal cord visualization via microsuspension laryngoscopy. Alternatively, the procedure can be done percutaneously via nasolaryngoscopy in an office setting and with the patient awake.

Awake procedures in these cases may be indicated if multiple comorbidities can make general anesthesia risky.[66] Additionally, office-based injection has the benefit of immediate feedback regarding dysphonia resolution. However, one limitation of this approach is that injection might not be as accurately placed or as easy as compared to augmentation in an anesthetized patient.[67](B2)

A more permanent surgical option is laryngeal framework surgery (medialization laryngoplasty or thyroplasty), commonly used in longstanding UVFP. The surgical detail of this procedure is beyond the scope of this article, but in brief, a window is made in the thyroid cartilage, and an implant is placed to medialize the true vocal fold. Various materials have been used, including Gore-Tex, Silastic implants, and Silicone blocks.[68]

Laryngeal reinnervation utilizes functioning nerves in the RLN's vicinity to reestablish laryngeal tone and movement. The ansa cervicalis, phrenic, and hypoglossal nerves have all been used as nerve pedicles with good voice outcomes[69].

Arytenoid adduction is specifically used to treat persistent or severe posterior glottic gaps.[54] A suture is suspended from the arytenoid muscular process anterior to the thyroid cartilage. Thus, the muscle can mimic the lateral cricoarytenoid's vocal-fold adducting effect. Although rarely used alone, this procedure may be a useful adjunct in treating UVFP in select cases.

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis of UVFP includes the conditions listed below. A thorough clinical evaluation and judicious use of diagnostic tests can help differentiate UVFP from these conditions.

- Allergy and environmental asthma

- Anaphylaxis

- Asthma

- Bilateral vocal fold paralysis

- Epiglottitis

- Exercise-induced asthma

- Foreign body obstruction

- Laryngeal abnormalities

- Laryngeal edema from C1 inhibitor deficiency or ACE inhibitor use

- Laryngeal spasm

- Upper respiratory tract infection

- Vocal polyps and nodules

Pertinent Studies and Ongoing Trials

Siu et al's systematic review revealed that injection thyroplasty, type 1 thyroplasty, laryngeal reinnervation, and arytenoid adduction do not exhibit significant differences in voice outcome or quality of life.[70] Type 1 Isshiki thyroplasty is often highly favored due to its greater long-term benefit over injection techniques. However, a growing body of evidence supports long-acting injectable materials' comparable longitudinal outcomes.[71] Thus, surgical intervention for UVFP should be reserved after a lack of response to a trial of conservative management has been demonstrated. The choice of surgical technique must be based on the surgeon's experience and patient preference.

Prognosis

The outlook for most patients with UVFP depends on the underlying pathology. Spontaneous recovery is expected in most individuals with idiopathic UVFP. However, cases with malignant and CNS etiologies have variable outcomes.[72]

Complications

The potential complications of UVFP include the following:

- Aspiration pneumonia

- Respiratory distress

- Dysphagia

- Decreased exercise tolerance

- Psychosocial effects of vocal changes

Underlying conditions like malignancies, thoracic injuries, and neurologic disease also bring unique sets of complications, such as debility, paraneoplastic syndromes, and death.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Preventing UVFP involves addressing its potential underlying causes and minimizing the risk of RLN damage. Measures that can help patients include taking precautions to avoid neck and throat trauma, treating infections promptly, and going to regular health checkups. Some UVFP risk factors are beyond an individual's control, but maintaining overall health can minimize the risk of complications that might lead to this condition.

For clinicians, head and neck surgical and instrumentation procedures must be performed carefully. Providers should seek to improve competence in performing common procedures like ETT insertion by continuous training and simulation.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In summary, UVFP is a relatively common disorder presenting to otolaryngologists and other medical practitioners. The condition can arise from RLN and laryngeal lesions from sources like malignancy and iatrogenic injuries. Some common symptoms are hoarseness, coughing, choking, aspiration, dyspnea, dysphagia, and globus sensation.

Once identified, imaging from the skull base superiorly to the aortic arch inferiorly is necessary to evaluate the RLN for any lesions. Treatment plans vary depending on the patient and etiology, but options are generally focused on airway protection and improving dysphonia. In idiopathic UVFP, spontaneous recovery can be expected in most patients after a year. Interval speech therapy may improve long-term outcomes. Early injection medialization has also been shown to improve final voice outcomes.

UVFP is best managed with an interprofessional approach. Both primary care providers and specialists in clinical practice encounter this disorder often. Referral to an otolaryngologist is highly recommended for formal laryngoscopic evaluation, emphasizing the need for comprehensive care in UVFP cases. Early referral for speech therapy is beneficial in nearly all patients. The anesthesiologist may be involved if the vocal-fold-augmentation procedure is performed under general anesthesia. Surgical nurses' services are crucial in caring for patients with UVFP admitted for surgical augmentation or respiratory distress.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Ling XY, Smoll NR. A systematic review of variations of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2016 Jan:29(1):104-10. doi: 10.1002/ca.22613. Epub 2015 Oct 5 [PubMed PMID: 26297484]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWatanabe K, Sato T, Honkura Y, Kawamoto-Hirano A, Kashima K, Katori Y. Characteristics of the Voice Handicap Index for Patients With Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis Who Underwent Arytenoid Adduction. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2020 Jul:34(4):649.e1-649.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.12.012. Epub 2019 Jan 5 [PubMed PMID: 30616964]

Zimmermann TM, Orbelo DM, Pittelko RL, Youssef SJ, Lohse CM, Ekbom DC. Voice outcomes following medialization laryngoplasty with and without arytenoid adduction. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Aug:129(8):1876-1881. doi: 10.1002/lary.27684. Epub 2018 Dec 24 [PubMed PMID: 30582612]

Naunheim ML, Yung KC, Schneider SL, Henderson-Sabes J, Kothare H, Hinkley LB, Mizuiri D, Klein DJ, Houde JF, Nagarajan SS, Cheung SW. Cortical networks for speech motor control in unilateral vocal fold paralysis. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Sep:129(9):2125-2130. doi: 10.1002/lary.27730. Epub 2018 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 30570142]

Qian XF, Chu YX, Xu YL, Wang YJ, Chen JL, Gao X. [Improved reinnervation of recurrent laryngeal nerve by ansa cervicalis for iatrogenic unilateral vocal fold paralysis]. Lin chuang er bi yan hou tou jing wai ke za zhi = Journal of clinical otorhinolaryngology, head, and neck surgery. 2018 Jul:32(14):1106-1107. doi: 10.13201/j.issn.1001-1781.2018.14.016. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30550158]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRosenthal LH, Benninger MS, Deeb RH. Vocal fold immobility: a longitudinal analysis of etiology over 20 years. The Laryngoscope. 2007 Oct:117(10):1864-70 [PubMed PMID: 17713451]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCantarella G, Dejonckere P, Galli A, Ciabatta A, Gaffuri M, Pignataro L, Torretta S. A retrospective evaluation of the etiology of unilateral vocal fold paralysis over the last 25 years. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2017 Jan:274(1):347-353. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4225-9. Epub 2016 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 27455863]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDavis RJ, Messing B, Cohen NM, Akst LM. Voice Quality and Laryngeal Findings in Patients With Suspected Lung Cancer. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2022 Jan:166(1):133-138. doi: 10.1177/01945998211008382. Epub 2021 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 33874792]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceTerris DJ, Arnstein DP, Nguyen HH. Contemporary evaluation of unilateral vocal cord paralysis. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1992 Jul:107(1):84-90 [PubMed PMID: 1528608]

Espinosa MC, Ongkasuwan J. Recurrent laryngeal nerve reinnervation: is this the standard of care for pediatric unilateral vocal cord paralysis? Current opinion in otolaryngology & head and neck surgery. 2018 Dec:26(6):431-436. doi: 10.1097/MOO.0000000000000499. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30300212]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen HC, Pei YC, Fang TJ. Risk factors for thyroid surgery-related unilateral vocal fold paralysis. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Jan:129(1):275-283. doi: 10.1002/lary.27336. Epub 2018 Oct 3 [PubMed PMID: 30284255]

Nerurkar NK, Dighe SN. Anatomical Course of the Thyroarytenoid Branch of the Recurrent Laryngeal Nerve. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Mar:129(3):704-708. doi: 10.1002/lary.27491. Epub 2018 Sep 12 [PubMed PMID: 30208213]

Sheahan P, O'Connor A, Murphy MS. Risk factors for recurrent laryngeal nerve neuropraxia postthyroidectomy. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2012 Jun:146(6):900-5. doi: 10.1177/0194599812440401. Epub 2012 Mar 7 [PubMed PMID: 22399281]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYang S, Zhou L, Lu Z, Ma B, Ji Q, Wang Y. Systematic review with meta-analysis of intraoperative neuromonitoring during thyroidectomy. International journal of surgery (London, England). 2017 Mar:39():104-113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.086. Epub 2017 Jan 25 [PubMed PMID: 28130189]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKadakia S, Mourad M, Hu S, Brown R, Lee T, Ducic Y. Utility of intraoperative nerve monitoring in thyroid surgery: 20-year experience with 1418 cases. Oral and maxillofacial surgery. 2017 Sep:21(3):335-339. doi: 10.1007/s10006-017-0637-y. Epub 2017 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 28577127]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSchneider R, Machens A, Sekulla C, Lorenz K, Elwerr M, Dralle H. Superiority of continuous over intermittent intraoperative nerve monitoring in preventing vocal cord palsy. The British journal of surgery. 2021 May 27:108(5):566-573. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11901. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34043775]

Cohen ER, Dable CL, Iglesias T, Singh E, Ma R, Rosow DE. Clinical Predictors of Postintubation Bilateral Vocal Fold Immobility. International archives of otorhinolaryngology. 2022 Oct:26(4):e524-e532. doi: 10.1055/s-0041-1741435. Epub 2022 Feb 4 [PubMed PMID: 36405471]

Wang HW, Lu CC, Chao PZ, Lee FP. Causes of Vocal Fold Paralysis. Ear, nose, & throat journal. 2022 Aug:101(7):NP294-NP298. doi: 10.1177/0145561320965212. Epub 2020 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 33090900]

Urquhart AC, St Louis EK. Idiopathic vocal cord palsies and associated neurological conditions. Archives of otolaryngology--head & neck surgery. 2005 Dec:131(12):1086-9 [PubMed PMID: 16365222]

Taşlı H, Kara U, Gökgöz MC, Aydın Ü. Vocal Cord Paralysis Following Endotracheal Intubation. Turkish journal of anaesthesiology and reanimation. 2017 Oct:45(5):321-322. doi: 10.5152/TJAR.2017.91297. Epub 2017 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 29114421]

Rubin F, Villeneuve A, Alciato L, Slaïm L, Bonfils P, Laccourreye O. Idiopathic unilateral vocal-fold paralysis in the adult. European annals of otorhinolaryngology, head and neck diseases. 2018 Jun:135(3):171-174. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2018.01.004. Epub 2018 May 7 [PubMed PMID: 29402673]

Masroor F, Pan DR, Wei JC, Ritterman Weintraub ML, Jiang N. The incidence and recovery rate of idiopathic vocal fold paralysis: a population-based study. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2019 Jan:276(1):153-158. doi: 10.1007/s00405-018-5207-x. Epub 2018 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 30443781]

Comparison of Clinical Characteristics Between Patients With Different Causes of Vocal Cord Immobility., Kim MH,Noh J,Pyun SB,, Annals of rehabilitation medicine, 2017 Dec [PubMed PMID: 29354579]

Kay-Rivest E, Mitmaker E, Payne RJ, Hier MP, Mlynarek AM, Young J, Forest VI. Preoperative vocal cord paralysis and its association with malignant thyroid disease and other pathological features. Journal of otolaryngology - head & neck surgery = Le Journal d'oto-rhino-laryngologie et de chirurgie cervico-faciale. 2015 Sep 11:44(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s40463-015-0087-1. Epub 2015 Sep 11 [PubMed PMID: 26362432]

O'Duffy F, Timon C. Vocal fold paralysis in the presence of thyroid disease: management strategies. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2013 Aug:127(8):768-72. doi: 10.1017/S0022215113001552. Epub 2013 Jul 30 [PubMed PMID: 23899778]

Bergamaschi R, Becouarn G, Ronceray J, Arnaud JP. Morbidity of thyroid surgery. American journal of surgery. 1998 Jul:176(1):71-5 [PubMed PMID: 9683138]

Hermann M, Alk G, Roka R, Glaser K, Freissmuth M. Laryngeal recurrent nerve injury in surgery for benign thyroid diseases: effect of nerve dissection and impact of individual surgeon in more than 27,000 nerves at risk. Annals of surgery. 2002 Feb:235(2):261-8 [PubMed PMID: 11807367]

Francis DO, Pearce EC, Ni S, Garrett CG, Penson DF. Epidemiology of vocal fold paralyses after total thyroidectomy for well-differentiated thyroid cancer in a Medicare population. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2014 Apr:150(4):548-57. doi: 10.1177/0194599814521381. Epub 2014 Jan 30 [PubMed PMID: 24482349]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceChang TL, Fang TJ, Wong AMK, Wu CF, Pei YC. Clinical and functional characteristics of lung surgery-related vocal fold palsy. Biomedical journal. 2021 Dec:44(6 Suppl 1):S101-S109. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2020.07.005. Epub 2020 Jul 27 [PubMed PMID: 35735079]

Scholtemeijer MG, Seesing MFJ, Brenkman HJF, Janssen LM, van Hillegersberg R, Ruurda JP. Recurrent laryngeal nerve injury after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer: incidence, management, and impact on short- and long-term outcomes. Journal of thoracic disease. 2017 Jul:9(Suppl 8):S868-S878. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.92. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28815085]

Plowman EK, Chheda N, Anderson A, Dallal York J, DiBiase L, Vasilopoulos T, Arnaoutakis G, Beaver T, Martin T, Bateh T, Jeng EI. Vocal Fold Mobility Impairment After Cardiovascular Surgery: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Sequela. The Annals of thoracic surgery. 2021 Jul:112(1):53-60. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.07.074. Epub 2020 Oct 17 [PubMed PMID: 33075318]

Tan TP, Govindarajulu AP, Massicotte EM, Venkatraghavan L. Vocal cord palsy after anterior cervical spine surgery: a qualitative systematic review. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2014 Jul 1:14(7):1332-42. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2014.02.017. Epub 2014 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 24632183]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceTran Y, Shah AK, Mittal S. Lead breakage and vocal cord paralysis following blunt neck trauma in a patient with vagal nerve stimulator. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2011 May 15:304(1-2):132-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.02.022. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21397256]

Levine RJ, Sanders AB, LaMear WR. Bilateral vocal cord paralysis following blunt trauma to the neck. Annals of emergency medicine. 1995 Feb:25(2):253-5 [PubMed PMID: 7832358]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReece GP, Shatney CH. Blunt injuries of the cervical trachea: review of 51 patients. Southern medical journal. 1988 Dec:81(12):1542-8 [PubMed PMID: 3059518]

Saeg AAA, Alnori H. Laryngeal injury and dysphonia after endotracheal intubation. Journal of medicine and life. 2021 May-Jun:14(3):355-360. doi: 10.25122/jml-2020-0148. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34377201]

Fujii-Abe K, Ikeda M, Yajima M, Kawahara H. A Case of Anterior Arytenoid Cartilage Dislocation During Nasal Tracheal Intubation Using an Indirect Video Laryngoscope. Anesthesia progress. 2023 Dec 1:70(4):191-193. doi: 10.2344/837325. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38221697]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBaker E, Lui F. Neuroanatomy, Vagal Nerve Nuclei. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31424793]

Tessler I, Primov-Fever A, Soffer S, Anteby R, Gecel NA, Livneh N, Alon EE, Zimlichman E, Klang E. Deep learning in voice analysis for diagnosing vocal cord pathologies: a systematic review. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2024 Feb:281(2):863-871. doi: 10.1007/s00405-023-08362-6. Epub 2023 Dec 13 [PubMed PMID: 38091100]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLiu KC, Lu YA, Lee LA, Li HY, Wong AM, Pei YC, Fang TJ. Cricothyroid Muscle Dysfunction Affects Aerodynamic Performance in Patients with Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2024 Jan:38(1):219-224. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2021.07.002. Epub 2021 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 34426048]

Pillutla P, Zhang Z, Chhetri DK. Effects of Arytenoid Adduction Suture Position on Voice Production and Quality. The Laryngoscope. 2021 Apr:131(4):846-852. doi: 10.1002/lary.28903. Epub 2020 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 32710654]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceXu X, Zhuang P, Wilson A, Jiang JJ. Compensatory Movement of Contralateral Vocal Folds in Patients With Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2021 Mar:35(2):328.e23-328.e28. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2019.09.010. Epub 2019 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 31653598]

Kono T, Tomisato S, Ozawa H. Effectiveness of vocal fold medialization surgery on the swallowing function of patients with unilateral vocal fold paralysis. Laryngoscope investigative otolaryngology. 2023 Aug:8(4):1007-1013. doi: 10.1002/lio2.1125. Epub 2023 Jul 28 [PubMed PMID: 37621299]

Johnson PR, Kanegoanker GS, Bates T. Indirect laryngoscopic evaluation of vocal cord function in patients undergoing transhiatal esophagectomy. Journal of the American College of Surgeons. 1994 Jun:178(6):605-8 [PubMed PMID: 8193754]

Cohen SM, Elackattu A, Noordzij JP, Walsh MJ, Langmore SE. Palliative treatment of dysphonia and dysarthria. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2009 Feb:42(1):107-21, x. doi: 10.1016/j.otc.2008.09.010. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19134494]

Arviso LC, Johns MM 3rd, Mathison CC, Klein AM. Long-term outcomes of injection laryngoplasty in patients with potentially recoverable vocal fold paralysis. The Laryngoscope. 2010 Nov:120(11):2237-40. doi: 10.1002/lary.21143. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20939083]

Lovato A, Barillari MR, Giacomelli L, Gamberini L, de Filippis C. Predicting the Outcome of Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis: A Multivariate Discriminating Model Including Grade of Dysphonia, Jitter, Shimmer, and Voice Handicap Index-10. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2019 May:128(5):447-452. doi: 10.1177/0003489419826597. Epub 2019 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 30693800]

Sercarz JA, Berke GS, Ming Y, Gerratt BR, Natividad M. Videostroboscopy of human vocal fold paralysis. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1992 Jul:101(7):567-77 [PubMed PMID: 1626902]

Daggumati S, Panossian M D H, Sataloff M D D M A F A C S RT. Vocal Fold Paresis: Incidence, and the Relationship between Voice Handicap Index and Laryngeal EMG Findings. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2019 Nov:33(6):940-944. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.05.008. Epub 2018 Jul 17 [PubMed PMID: 30025622]

Hamdan AL, Rizk M, Khalifee E, Ziade G, Kasti M. Voice outcome measures after flexible endoscopic injection laryngoplasty. World journal of otorhinolaryngology - head and neck surgery. 2018 Jun:4(2):130-134. doi: 10.1016/j.wjorl.2018.04.005. Epub 2018 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 30101223]

Bilici S, Yildiz M, Yigit O, Misir E. Imaging Modalities in the Etiologic Evaluation of Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2019 Sep:33(5):813.e1-813.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2018.04.017. Epub 2018 May 18 [PubMed PMID: 29785934]

McLaughlin CW, Swendseid B, Courey MS, Schneider S, Gartner-Schmidt JL, Yung KC. Long-term outcomes in unilateral vocal fold paralysis patients. The Laryngoscope. 2018 Feb:128(2):430-436. doi: 10.1002/lary.26900. Epub 2017 Nov 24 [PubMed PMID: 29171729]

Krasnodębska P, Miaśkiewicz B, Szkiełkowska A. Electromyographic Evaluation of Vocal Folds in Patients With Laryngeal Paralysis Referred for Injection Laryngoplasty. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2023 Nov 15:():. pii: S0892-1997(23)00185-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2023.06.010. Epub 2023 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 37977968]

Watanabe K, Hirano A, Kobayashi Y, Sato T, Honkura Y, Katori Y. Correction: Long-term voice evaluation after arytenoid adduction surgery in patients with unilateral vocal fold paralysis. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2023 Dec 30:():. doi: 10.1007/s00405-023-08422-x. Epub 2023 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 38159220]

Kaefer SL, Zhang L, Morrison RA, Brookes S, Awonusi O, Shay E, Hoilett OS, Anderson JL, Goergen CJ, Voytik-Harbin S, Halum S. Early Changes in Porcine Larynges Following Injection of Motor-Endplate Expressing Muscle Cells for the Treatment of Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis. The Laryngoscope. 2024 Jan:134(1):272-282. doi: 10.1002/lary.30868. Epub 2023 Jul 12 [PubMed PMID: 37436167]

Sulica L. The natural history of idiopathic unilateral vocal fold paralysis: evidence and problems. The Laryngoscope. 2008 Jul:118(7):1303-7. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31816f27ee. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18496160]

Kissel I, D'haeseleer E, Meerschman I, Wackenier E, Van Lierde K. Clinical Experiences of Speech-Language Pathologists in the Rehabilitation of Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2023 May 6:():. pii: S0892-1997(23)00134-0. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2023.04.010. Epub 2023 May 6 [PubMed PMID: 37156684]

Chow XH, Johari SF, Rosla L, Wahab AFA, Azman M, Baki MM. Early Transthyrohyoid Injection Laryngoplasty Under Local Anaesthesia in a Single Tertiary Center of Southeast Asia: Multidimensional Voice Outcomes. Turkish archives of otorhinolaryngology. 2021 Dec:59(4):271-281. doi: 10.4274/tao.2021.2021-8-12. Epub 2022 Feb 22 [PubMed PMID: 35262044]

Lahav Y, Malka-Yosef L, Shapira-Galitz Y, Cohen O, Halperin D, Shoffel-Havakuk H. Vocal Fold Fat Augmentation for Atrophy, Scarring, and Unilateral Paralysis: Long-term Functional Outcomes. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2021 Mar:164(3):631-638. doi: 10.1177/0194599820947000. Epub 2020 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 32777994]

Watanabe K, Hirano A, Honkura Y, Kashima K, Shirakura M, Katori Y. Complications of using Gore-Tex in medialization laryngoplasty: case series and literature review. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2019 Jan:276(1):255-261. doi: 10.1007/s00405-018-5204-0. Epub 2018 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 30426228]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOdland RM, Wigley T, Rice R. Management of unilateral vocal fold paralysis. The American surgeon. 1995 May:61(5):438-43 [PubMed PMID: 7733552]

Hertegård S, Hallén L, Laurent C, Lindström E, Olofsson K, Testad P, Dahlqvist A. Cross-linked hyaluronan used as augmentation substance for treatment of glottal insufficiency: safety aspects and vocal fold function. The Laryngoscope. 2002 Dec:112(12):2211-9 [PubMed PMID: 12461343]

Prendes BL, Yung KC, Likhterov I, Schneider SL, Al-Jurf SA, Courey MS. Long-term effects of injection laryngoplasty with a temporary agent on voice quality and vocal fold position. The Laryngoscope. 2012 Oct:122(10):2227-33. doi: 10.1002/lary.23473. Epub 2012 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 22865287]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMcCulloch TM, Andrews BT, Hoffman HT, Graham SM, Karnell MP, Minnick C. Long-term follow-up of fat injection laryngoplasty for unilateral vocal cord paralysis. The Laryngoscope. 2002 Jul:112(7 Pt 1):1235-8 [PubMed PMID: 12169905]

Reijonen P, Tervonen H, Harinen K, Rihkanen H, Aaltonen LM. Long-term results of autologous fascia in unilateral vocal fold paralysis. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2009 Aug:266(8):1273-8. doi: 10.1007/s00405-009-0924-9. Epub 2009 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 19241085]

Haddad R, Mattei A, Giovanni A. Local anesthesia with blue-dyed lidocaine for a better patient's tolerance during office-based laryngology procedures: how I do it. European archives of oto-rhino-laryngology : official journal of the European Federation of Oto-Rhino-Laryngological Societies (EUFOS) : affiliated with the German Society for Oto-Rhino-Laryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2023 Nov:280(11):5139-5141. doi: 10.1007/s00405-023-08146-y. Epub 2023 Jul 25 [PubMed PMID: 37490180]

Chandran D, Woods C, Ullah S, Ooi E, Athanasiadis T. A comparative study of voice outcomes and complication rates in patients undergoing injection laryngoplasty performed under local versus general anaesthesia: an Adelaide voice specialist's experience. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2017 Jan:131(S1):S41-S46. doi: 10.1017/S0022215116009221. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28164775]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKostas JC, Lee M, Rameau A. A Novel Low-Cost, Open-Source, Three-Dimensionally Printed Thyroplasty Simulator. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2023 Nov 29:():. pii: S0892-1997(23)00376-4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2023.11.016. Epub 2023 Nov 29 [PubMed PMID: 38036381]

Meenan K, Pillutla P, Chhetri DK. Is Laryngeal Reinnervation Recommended for Pediatric Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis? The Laryngoscope. 2023 Sep 26:():. doi: 10.1002/lary.31074. Epub 2023 Sep 26 [PubMed PMID: 37750564]

Siu J, Tam S, Fung K. A comparison of outcomes in interventions for unilateral vocal fold paralysis: A systematic review. The Laryngoscope. 2016 Jul:126(7):1616-24. doi: 10.1002/lary.25739. Epub 2015 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 26485674]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceUmeno H, Chitose S, Sato K, Ueda Y, Nakashima T. Long-term postoperative vocal function after thyroplasty type I and fat injection laryngoplasty. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2012 Mar:121(3):185-91 [PubMed PMID: 22530479]

Walton C, Carding P, Conway E, Flanagan K, Blackshaw H. Voice Outcome Measures for Adult Patients With Unilateral Vocal Fold Paralysis: A Systematic Review. The Laryngoscope. 2019 Jan:129(1):187-197. doi: 10.1002/lary.27434. Epub 2018 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 30229922]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence