Definition/Introduction

The Koebner phenomenon (KP), first described in 1876 by Heinrich Koebner, is the appearance of new skin lesions on previously unaffected skin secondary to trauma.[1] This phenomenon is also termed the isomorphic (from Greek, “equal shape”) response, given that the new lesions appear clinically and histologically identical to the patient’s underlying cutaneous disease.[2] In other words, a patient with psoriasis who exhibits koebnerization (and is said to be “Koebner-positive”) develops new psoriasiform lesions along sites of skin injury, even if trivial. Koebner phenomenon can develop in any anatomic site, including in classic areas of psoriatic involvement and in regions that are usually spared, such as the face. The phenomenon shows dynamic behavior. Patients may be “Koebner-negative” at 1 point in life but may later become “Koebner-positive.”[1]

The Koebner phenomenon is not to be confused with pathergy, which is a term utilized to describe when minor trauma (including blunt trauma such as bumps and bruises) can induce skin lesions.[2] The lesions arising from pathergy tend to be non-specific papules or pustules that may develop into skin ulcers. Pathergy, commonly in conditions such as pyoderma gangrenosum Sweet syndrome and Bechet disease, is also used as a clinical diagnostic test. The site where pathergy positivity has been elicited often exhibits a monocytic infiltrate on histopathology.[2] In contrast, the lesions arising from the Koebner phenomenon reflect upon the patient's underlying skin disease, such as psoriasis or vitiligo.

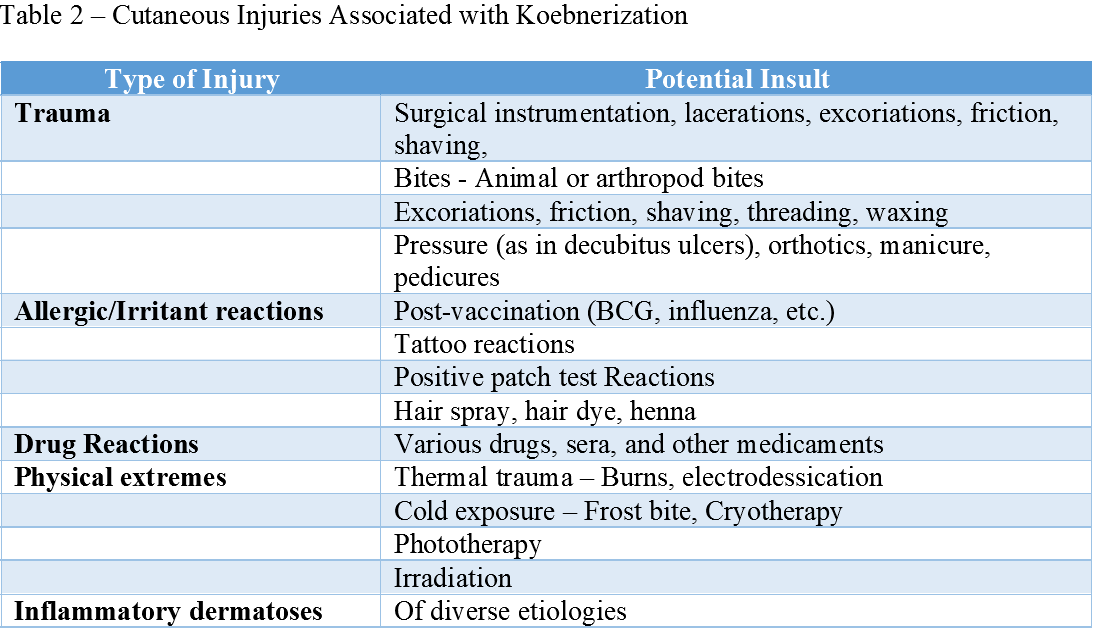

The Koebner phenomenon requires differentiation from the reverse Koebner phenomenon, which is the disappearance of skin lesions following trauma over the existing lesions.[3] When working on a differential diagnosis, it is also important to distinguish the Koebner phenomenon from the pseudo-Koebner phenomenon (also known as category II Koebner phenomenon as per the Boyd and Nelder classification), in which infectious agents (such as viruses) cause the spread of monomorphic lesions across previously unaffected skin (see Table. Classification of Koebner and Koebner-Related Responses).[4] The pseudo-Koebner phenomenon occurs with common infectious etiologies, such as molluscum contagiosum and verrucae [infective warts caused by human papillomavirus].[5] See Image. Pseudo-Koebnerization.

One should also differentiate the true Koebner phenomenon from Wolf’s isotopic response (see Image. True Koebner Phenomenon). Wolf’s isotopic response is similar to when trauma induces new skin lesions to appear on previously unaffected skin. However, unlike the Koebner phenomenon, the lesions in Wolf’s precede the appearance of generalized skin disease.[6]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Underlying Pathophysiology

The underlying pathophysiology of this phenomenon remains unclear.[1][2] The current thought is that it is immune-mediated, involving cytokines and autoantigens, or disease-specific reactions, such as T-cell mediated reactions, keratinocyte proliferation, and angiogenesis in psoriasis.[2] Other theories suggest that it is a vascular process, as it appears the microvasculature in psoriatic patients exhibiting Koebnerization responds differently to trauma. Some believe that the papillary dermis must be involved to induce a Koebner response, suggesting injury to epidermal cells and dermal inflammation are required—other possible underlying mechanisms include enzymatic, neural, genetic, infectious, and hormonal. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to support any particular theory over another.[4]

Classification and Subtypes of the Koebner Phenomenon

Boyd and Nelder classified clinical entities with reported Koebnerization into 4 categories: true Koebnerization, pseudo-Koebnerization, occasional traumatic localization of lesions, and poor or questionable trauma-induced processes.[4] (table 1)

The first group [category I], called true koebnerization, includes psoriasis, lichen planus, and vitiligo. In these 3 conditions, the Koebner phenomenon is reproducible in all patients by various insults. Boyd and Nelder argued that the term Koebner phenomenon should typically be reserved for this disease group.

The second group [category II], referred to as pseudo-koebnerization, includes diseases such as molluscum contagiosum and verruca vulgaris. The Koebner phenomenon is produced by the seeding of infectious agents along with sites subjected to trauma, usually from scratching.

The third group [category IIII], occasional lesions, includes Darier disease and erythema multiforme, which meet some criteria for the Koebner phenomenon but not all. Finally, the fourth group [category IV], questionable trauma-induced process, includes all disorders with a dubious association with trauma, such as pemphigus vulgaris and lupus erythematosus.

Since this publication in 1990, other conditions have demonstrated the Koebner phenomenon, such as leukocytoclastic vasculitis, mycosis fungoides, and eruptive xanthomas, among others mentioned in this topic.[7][8][9]

Type and Severity of Trauma Inducing Koebner Phenomenon

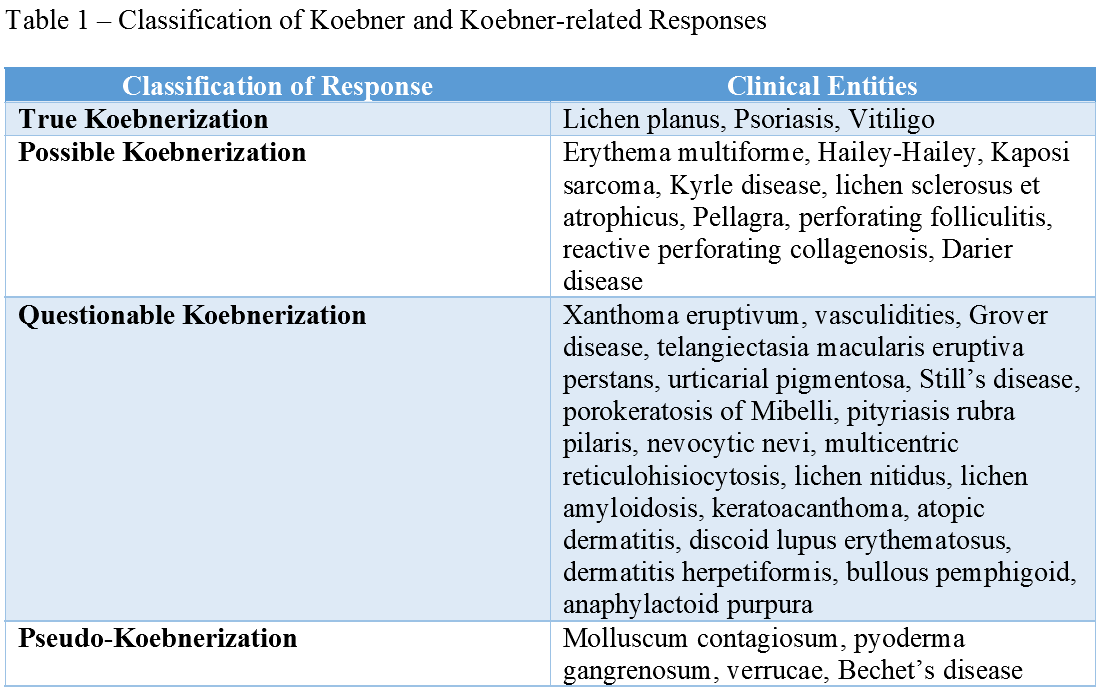

Different types of cutaneous injury may trigger this phenomenon, including excoriations, tattoos, friction, trauma, surgical instrumentation, burns, and ultraviolet or irradiation (see Table. Cutaneous Injuries Associated With Koebnerization).[1][2] The Koebner phenomenon exhibits an “all or nothing” pattern of reactivity, where a patient who reacts to 1 traumatic stimulus is likely to react to all stimuli, and a patient who does not react to a traumatic stimulus is likely to be non-reactive to all other stimuli as well.[10][11] The severity of the response varies, as well. Severity can be classified into 4 grades: none, abortive (lesions vanish spontaneously after approximately 2 weeks), minimal (focal lesions around the area of trauma), and maximal (wide-spread lesions).[2]

Time from skin insult to the appearance of new skin lesions varies. In psoriasis, new lesions typically arise within 10 to 20 days after a skin injury; however, this ranges from 3 days to 20 years.[2] The latent period between traumatic insult to the uninvolved skin and Boyd and Nelder considered the appearance of new lesions to be 10 to 14 days on average. However, Koebner has suggested the variability of the duration ranges from just 3 days to up to several years.[4][12] This wide range suggests varying sensitivity for developing the Koebner phenomenon, which may be a unique characteristic of the patient's skin or the underlying disease process. Moreover, diseases such as vitiligo and psoriasis typically have a waxing-waning course and may develop over different intervals after several simultaneous insults in the same patient.[1]

Clinical Significance

The Koebner phenomenon is typically associated with preexisting skin disease. Clinical entities commonly displaying the Koebner phenomenon include psoriasis, vitiligo, and lichen planus.[1] The incidence of Koebnerization ranges broadly within these entities; estimates of the prevalence of the Koebner phenomenon are approximately 11 to 75% in psoriasis and 21 to 62% in vitiligo.[4][13]

Koebnerization may significantly impact patients with psoriasis, as any insult to their skin, including tattoos and injections, can cause their disease to flare.[1] One study found that many patients surveyed had developed psoriasis within a few weeks following the tattooing process.[14] A minority had psoriasis limited to the tattoo site, but a larger subset of patients exhibited generalized psoriasis after tattooing.[14] Because the Koebner phenomenon is not a unique disease process but rather activation of underlying cutaneous disease, managing lesions arising from Koebnerization depends on managing the primary disease. Relative to vitiligo, studies have found that the affected body surface area is significantly higher when Koebnerization is present.[15] The presence of Koebnerization in vitiligo also appears to correlate with higher disease activity within the past 12 months. Lower response to treatment also appears to occur in vitiligo patients who exhibited Koebnerization. This study concluded that Koebnerization might function as a clinical indicator of disease activity in vitiligo and serve as a predictor of treatment response.[15]

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

Dermatologists often test for the Koebner phenomenon as part of a complete physical exam. However, by the time a patient reaches a dermatologist, it is almost certain that they received a referral from other providers because they have an underlying cutaneous disease. As a result, awareness of the Koebner phenomenon by other health professionals is likely to help patients faster diagnose and refer. Primary care providers and emergency medicine physicians may often be the first health care professionals to encounter a patient with cutaneous disease. It may be helpful for these specialties to incorporate testing for Koebnerization (with a scratch test) into their physical exam to aid in building their differential diagnosis. Additionally, nurses may be the first to notice when minimal trauma induces a cutaneous response in a patient (ie, a patient develops psoriasiform plaques along venipuncture sites or tape lines). Nurses may thus help the interprofessional team by reporting such findings.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

True Koebner Phenomenon. (A) In a patient with chronic plaque psoriasis. Appreciate the 'kissing' lesions of psoriasis developing along the natal cleft stemming from trivial friction-induced trauma; (B) In a patient with vitiligo vulgaris. Appreciate the linear depigmented macule over the back of patient (black arrow) with active vitiligo, which developed within a week of the patient having sustained a mild abrasion along that line; and (C) In lichen planus involving the neck fold of an adult man - Dermoscopic image highlighting the linearly arranged Wickham's striae (white structureless areas) for better clarity [Escope Videodermatoscope; 70X, polarized; Timpac Healthcare Pvt. Ltd.].

Contributed by S Sonthalia, MD, DNB, MNAMS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Pseudo-Koebnerization. (A) Flat warts in the threading area of a young lady; and (B) molluscum contagiosum (MC) lesions in an immunosuppressed patient. Note the florid lesions of genital MC and evidence of linear clusters at multiple places. One area (yellow circle) has been magnified in the inset for better appreciation. Visible as clustered papules (black circle). In these cases, microinoculation or seeding of the viral particles is responsible for this kind of Koebner phenomenon.

Contributed by S Sonthalia, MD, DNB, MNAMS

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Sagi L, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon. Clinics in dermatology. 2011 Mar-Apr:29(2):231-6. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2010.09.014. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21396563]

Ahad T, Agius E. The Koebner phenomenon. British journal of hospital medicine (London, England : 2005). 2015 Nov:76(11):C170-2. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2015.76.11.C170. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26551509]

Panta P, Andhavarapu A, Sarode SC, Sarode G, Patil S. Reverse Koebnerization in a linear oral lichenoid lesion: A case report. Clinics and practice. 2019 May 6:9(2):1144. doi: 10.4081/cp.2019.1144. Epub 2019 Jun 24 [PubMed PMID: 31312420]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoyd AS, Neldner KH. The isomorphic response of Koebner. International journal of dermatology. 1990 Jul-Aug:29(6):401-10 [PubMed PMID: 2204607]

Diani M, Cozzi C, Altomare G. Heinrich Koebner and His Phenomenon. JAMA dermatology. 2016 Aug 1:152(8):919. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.6015. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27532355]

Happle R, Kluger N. Koebner's sheep in Wolf's clothing: does the isotopic response exist as a distinct phenomenon? Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2018 Apr:32(4):542-543. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14664. Epub 2017 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 29080318]

Kassam F, Nurmohamed S, Haber RM. Koebner phenomenon in leukocytoclastic vasculitis: A case report and an updated review of the literature. SAGE open medical case reports. 2019:7():2050313X19850353. doi: 10.1177/2050313X19850353. Epub 2019 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 31205713]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLebas E,Libon F,Nikkels AF, Koebner Phenomenon and Mycosis Fungoides. Case reports in dermatology. 2015 Sep-Dec [PubMed PMID: 26557075]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWani AM, Hussain WM, Fatani MI, Qadmani A, Akhtar M, Maimani GA, Turkistani A, Bafaraj MG, Dairi KS. Eruptive xanthomas with Koebner phenomenon, type 1 diabetes mellitus, hypertriglyceridaemia and hypertension in a 41-year-old man. BMJ case reports. 2009:2009():. pii: bcr05.2009.1871. doi: 10.1136/bcr.05.2009.1871. Epub 2009 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 21866236]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWeiss G, Shemer A, Trau H. The Koebner phenomenon: review of the literature. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2002 May:16(3):241-8 [PubMed PMID: 12195563]

Camargo CM, Brotas AM, Ramos-e-Silva M, Carneiro S. Isomorphic phenomenon of Koebner: facts and controversies. Clinics in dermatology. 2013 Nov-Dec:31(6):741-9. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2013.05.012. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24160280]

SHELLEY WB,ARTHUR RP, Biochemical and physiological clues to the nature of psoriasis. A.M.A. archives of dermatology. 1958 Jul [PubMed PMID: 13544620]

Khurrum H, AlGhamdi KM, Bedaiwi KM, AlBalahi NM. Multivariate Analysis of Factors Associated with the Koebner Phenomenon in Vitiligo: An Observational Study of 381 Patients. Annals of dermatology. 2017 Jun:29(3):302-306. doi: 10.5021/ad.2017.29.3.302. Epub 2017 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 28566906]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKluger N. Tattooing and psoriasis: demographics, motivations and attitudes, complications, and impact on body image in a series of 90 Finnish patients. Acta dermatovenerologica Alpina, Pannonica, et Adriatica. 2017 Jun:26(2):29-32 [PubMed PMID: 28632882]

van Geel N, Speeckaert R, De Wolf J, Bracke S, Chevolet I, Brochez L, Lambert J. Clinical significance of Koebner phenomenon in vitiligo. The British journal of dermatology. 2012 Nov:167(5):1017-24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11158.x. Epub 2012 Sep 5 [PubMed PMID: 22950415]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence