Introduction

The gynecologic examination is a critical component of comprehensive women's healthcare. The pelvic exam traditionally includes a careful inspection of the external genitalia and a speculum and bimanual exam to assess the internal genitalia. Under some circumstances, a rectovaginal examination may also be appropriate to better characterize the posterior pelvis. The gynecologic examination is a critical diagnostic tool, enabling healthcare providers to assess and diagnose a broad spectrum of gynecological conditions, such as abnormal bleeding or discharge, pelvic pain, sexually transmitted infections (STIs), benign or malignant tumors, cysts, and anatomical abnormalities. Additionally, the exam can be part of obstetric and routine screening evaluations. An appropriate exam can help identify abnormalities, assess patients before performing procedures (eg, intrauterine device [IUD] insertion), and monitor women during their reproductive years.[1]

The gynecologic pelvic examination can pose several challenges for healthcare professionals. First, these are sensitive exams, often used to assess very private concerns that can cause patients to feel vulnerable, embarrassed, and/or physically uncomfortable. For this reason, excellent communication with the patient is essential, and the healthcare professional must be able to effectively explain the procedure and obtain informed consent while respecting a patient's concerns. Additionally, due to the sensitive nature of the procedure, it can be harder to practice and gain competence in this crucial skill.

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

External Genitalia

Collectively, the external female genitalia is referred to as the vulva and includes the mons pubis, labia majora and minora, clitoris, vulvar vestibule, vestibular bulbs, Skene's and Bartholin glands, vaginal introitus, urethral meatus, and perineum.[2][3][4]

The mons pubis is a rounded area of fatty tissue overlying the pubic symphysis. Inferior to the mons pubis are the labia majora, paired structures containing skin and adipose tissue. Both the mons pubis and lateral surfaces of the labia majora naturally grow pubic hair, though the medial surface of the labia majora is typically hairless. On each side of the body, medial to the labia majora, is the thinner, hairless labia minora, which can vary widely in size. The almond-shaped space between the labia minora is known as the vestibule. The urethral meatus can be found just anterior to the vaginal orifice within the vestibule and typically takes the shape of a sagittal cleft. The perineum is the area located posterior to the labia majora extending to the anus.

The clitoris is visible as a small projection of erectile tissue located in the midline at the anterior aspect of the labia, inferior to the mons pubis. Typically, there is a flap of skin that overlies the clitoris that arises from the anterior confluence of the labia minora and is known as the clitoral hood or prepuce. The small visible portion of the clitoris is known as the glans. The internal portion of the clitoris forms a "Y"-shaped structure, consisting of the body, which passes internally in the midline inferior to the pubic symphysis, and a pair of crura, which anchor the clitoris laterally to the inferior edges of the pubic arch.[5][6]

Deep to the labia majora are 2 elongated masses of erectile tissue known as the vestibular bulbs. The vestibular bulbs originate at the midline anteriorly and extend posteriorly to wrap around the lateral aspects of the vaginal orifice. On each side of the vagina, posterior to the vestibular bulbs (at the 4 o'clock and 8 o'clock positions when a patient is in the lithotomy position), are the greater vestibular glands, also known as the Bartholin glands, which secrete fluid that keeps the vagina moist and provides additional lubrication during intercourse. Under normal circumstances, these glands are each approximately the size of a pea and neither visible nor palpable. However, if the glands are occluded, they can become enlarged and infected, which is exquisitely painful. The paraurethral glands, also known as Skene glands, are located on both sides of the urinary meatus within the vestibule and are homologous to the male prostate.

Internal Genitalia

The internal female genitalia includes the vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries. The bladder, rectovaginal septum, and pelvic floor musculature can also be assessed on an internal pelvic exam.

The vagina is a muscular, elastic canal, typically 8 to 10 cm in length, that extends from the vulva to the protrusion of the cervix. The vaginal mucosa is folded into thick ridges called vaginal rugae, which create friction during intercourse to stimulate the penis. The vagina is acidic under normal circumstances, with a pH of approximately 3.5 to 4.0, due to bacteria converting glycogen in the epithelial cells to lactic acid.

The hymen is a thin membrane of tissue that partially covers the vaginal orifice near the distal end of the vagina at birth. There are many variations to the shape of the hymen, and it may be difficult to identify after hymenal rupture, which can occur during the first act of intercourse, masturbation, tampon use, pelvic examination, injury, or even physical exercise.

The cervix is the distalmost portion of the uterus. It is a thick fibromuscular, canulated organ that connects the uterine cavity to the vaginal canal. The cervix is visible on a speculum exam protruding into the proximal end of the vagina, known as the fornix. The distal end of the cervical canal is the external os, and the proximal end is the internal os. In obstetrics, "cervical dilation" refers to dilation of the internal os.

The uterus is a triangle-shaped thick muscular organ within the pelvis that opens into the vagina through the cervix at its lower end. The broad superior curvature of the uterus is the fundus, and the uterus typically averages about 7 cm in length from the cervix to the fundus in a nongravid individual. The uterine wall is made up of thick layers of smooth muscle, and the uterine cavity is lined with mucosa, known as the endometrium. The uterus can be examined on bimanual palpation to assess its size, shape, position, and mobility.

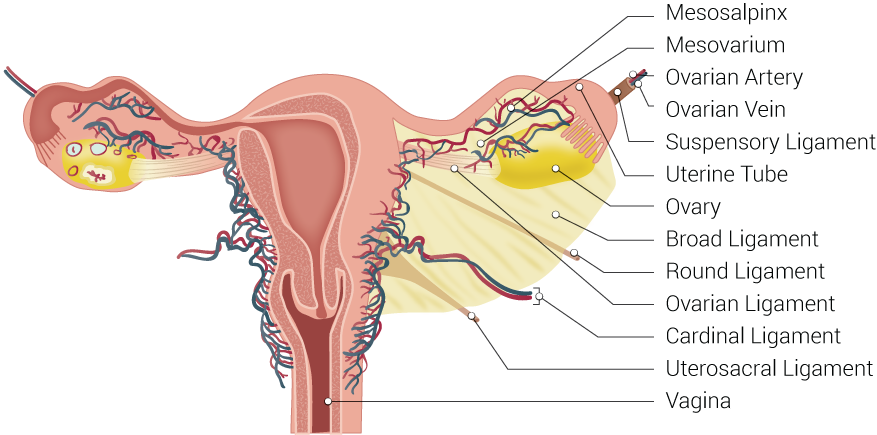

The uterine cavity opens into 2 fallopian tubes superolaterally (1 on each side). These tubes are approximately 10 cm long and connect the uterine cavity with the ovaries; however, they are typically not palpable on examination unless they contain a mass (see Image. Uterine Tubal Anatomy and Ligaments). The ovaries are almond-shaped glands located lateral to the uterus within the pelvic cavity and about 2 to 3 cm in size, though they are typically much smaller in postmenopausal patients.

Indications

Examinations to Assess Gynecologic Symptoms

A pelvic examination is used to assess the external and internal female genital structures. The urethra, bladder, perineum, anus, and/or rectum are also frequently evaluated at the same time.[7]

A pelvic examination is warranted to assess patients with relevant symptoms or concerns as follows:

- Abnormal bleeding, including menstrual abnormalities and postcoital and postmenopausal bleeding

- Pelvic pain, such as dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, or dyschezia

- Abnormal vaginal discharge

- Itching

- Masses

- Visible lesions or ulcers

- Infertility

- Trauma

- Retained foreign bodies [8]

- Concerns regarding abnormal anatomy or development

- Neurological conditions

- Incontinence

- Prolapse or other pelvic floor disorders [9]

- Unexplained new gastrointestinal symptoms (eg, difficulty eating, early satiety, abdominal pain, bloating, etc) [7][10]

Additionally, during pregnancy, a pelvic exam is warranted to assess patients with bleeding, cramping, contractions, and loss of amniotic fluid and to monitor patients during the intrapartum period.

Routine Screening Examinations

The gynecologic pelvic examination has traditionally been a part of routine screening assessments in asymptomatic, nonpregnant women to screen for gynecologic cancers and infections. However, more recent data has questioned the utility of these exams as cancer screening guidelines have changed and newer, less invasive STI tests have been developed.[11] Specifically, the limited data that exists suggests that screening asymptomatic individuals does not improve outcomes for benign gynecologic conditions, such as genital herpes or bacterial vaginosis, and noncervical gynecologic malignancies, including ovarian cancer.[7][11][12][13] This is potentially due to poor diagnostic accuracy for detecting ovarian cancer or benign conditions in asymptomatic patients.[1][13]

Due to the limited evidence of benefit, guidelines vary somewhat regarding screening pelvic exams. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that clinicians discuss the risks and benefits of a screening gynecologic exam with their asymptomatic patients and decide together whether or not to perform the exam.[11] On the other hand, the American College of Physicians (ACP) recommends against screening exams in asymptomatic women, and the US Preventative Services Task Force 2017 guideline states that there is insufficient evidence to assess the balance of benefits versus harms.[1][12][14]

Reasons to consider performing a screening pelvic exam include the possible early detection of a treatable vulvar or vaginal cancer before the appearance of symptoms, identifying abnormal anatomy or foreign bodies, and providing an opportunity for patients to ask questions about their reproductive health they would not have otherwise mentioned. The exam also allows the clinician a chance to ask about potential findings that the patient may not have realized were abnormal (eg, pigmented vulvar lesions and abnormal vaginal discharge).[7][11] Although the exam can be uncomfortable, 1 study found that 82% of respondents felt that the examination provided reassurance about their health.[15]

There is low-quality evidence to suggest the gynecologic pelvic exam may cause potential harm, including pain or discomfort, anxiety, fear, and embarrassment, especially if the patient has a history of sexual violence.[1]

It should be noted that a gynecologic exam is not required before prescribing hormonal contraception to healthy asymptomatic individuals.[7][16]

Contraindications

The only absolute contraindication is a lack of consent for the procedure.[17]

Equipment

The pelvic examination is typically performed on a flat surface or examining table, preferably 1 with foot supports or stirrups.[18][17] A drape or absorbent pad is typically placed beneath the patient's buttocks, and the patient should be covered with a drape from the waist down to preserve modesty. Exam gloves, a speculum, a light source, and water-soluble lubricant are needed to complete the internal portion of the exam. Supplies for obtaining cultures or other diagnostic tests should be readily available if abnormal findings (eg, purulent discharge) are encountered.

Specula come in various sizes and styles; however, the Pedersen and Graves specula are the 2 most commonly used. The Graves speculum is designed to be self-retaining once inserted into the vagina. It is wider than the Pederson speculum and is generally reserved for parous women. The Pederson speculum is narrower and often the most comfortable for women, though these specula are not self-retaining and must be held in place throughout the exam. Pediatric specula, which are much shorter and narrower than specula designed for adolescents and adults, are also available.

Metal specula are not disposable and require sterilization between each use, while plastic specula are single-use disposable items. Many plastic specula are designed to be used with a fiberoptic light source that improves visibility; however, metal specula require an adjustable lamp. Simple room lighting will not be adequate for the examination.

Personnel

It is best to perform a gynecologic exam in the presence of a chaperone for both the patient's and provider's security, although there is little evidence suggesting that the presence of a chaperone reduces litigation.[19][18] Typically, a medical assistant or nurse functions as a chaperone while assisting the clinician in performing the examination.

Preparation

Informed Consent

Informed consent should be obtained before starting the examination. The provider should discuss the indications for the exam with the patient and describe all components of the exam that are to be performed.[18][17]

Patient Positioning

The patient should be undressed from the waist down and covered with a sheet to maintain modesty. The patient should be uncovered for the shortest duration possible and only during the exam. She should remain draped until properly positioned.

Gynecologic exams are best performed with patients in the dorsal lithotomy position using foot supports (see Image. Lithotomy Position for Urologic and Gynecologic Procedures). The patient should be instructed to position herself with her buttocks extending slightly past the edge of the table so that the vaginal orifice is in line with or just past the edge of the table. This positioning is required because the table itself will obstruct the insertion of the speculum into the vagina. If a table with foot supports is unavailable, space for the speculum can be created by placing the patient’s hips on top of a padded, upside-down bedpan. Her legs may be flexed at the hips and knees, or she may be placed in a frog-leg position with the soles of her feet together. If a speculum exam is not planned (eg, evaluation of external genitalia in a pediatric or postpartum patient), the frog-leg position is also appropriate.

Technique or Treatment

The gynecologic exam typically includes an inspection of the external genitalia, a speculum exam to inspect the vagina and cervix, and a bimanual exam to assess the uterus and adnexa by palpation. In some situations, a rectovaginal exam may also be appropriate; however, this step is often omitted.

Inspection of External Genitalia

The exam should start with a visual evaluation of the external genitalia. Inform the patient the exam is beginning and inspect the mons pubis, labia, clitoris, and perineum. The clinician should note the basic development of vulvar anatomy, symmetry, hair distribution, and any swelling, bruising, erythema, rashes, lesions, nodules, masses, or discharge. Palpation can further characterize visual abnormalities and provide information about a mass or nodule's tenderness, size, mobility, and construct.[18][17] Masses can be palpated by placing the thumb on the labia with the index finger in the vaginal introitus, capturing the mass between the digits. The labia should then be gently separated, allowing for better inspection of the labia minora, as well as the vestibule, vaginal introitus, and urethral meatus.

Prolapse can be assessed by asking the patient to bear down and observing the movement of the internal vaginal walls and uterus. A complete examination of pelvic organ prolapse (known as the POP-Q exam) is beyond the scope of this review.

Speculum Examination

The speculum exam typically follows an inspection of the external genitalia. First, the blades of the speculum should be lubricated. The speculum is held in the palm of 1 hand, with the blades extending between the index and middle fingers, which keeps them closed. The examiner then spreads the labia slightly with the other hand and then enlarges the introitus slightly by applying gentle downward pressure at the lower margin of the vagina.

When inserting the speculum, the blades should be rotated about 45 ° off the midline (ie, so that the top of the speculum is at about the 2 or 10 o'clock position) and directed posteriorly toward the sacrum. Once the speculum has entered the vagina, the examiner's hand is removed from the vagina. The speculum is then rotated to an upright position (ie, so the top of the speculum is at the 12 o'clock position) and inserted to its full length. During insertion, gentle downward pressure is applied with the speculum itself, which helps reduce discomfort from the speculum sliding against the sensitive urethra anteriorly. The clinician should take care to ensure no pubic hair or tissue is caught within the speculum during insertion.

With proper insertion technique, the inferior blade of the speculum should be placed in the posterior fornix of the vagina. The speculum is then opened carefully until it cups the cervix. The cervix will appear as a smooth, firm, bulge of tissue compared to the surrounding rugated vaginal mucosa. If the cervix is difficult to identify, the speculum should be withdrawn slightly, repositioned, and reopened. If the uterus is anteverted, the cervix is directed toward the posterior vaginal fornix, while a retroverted uterus will result in a more anterior position of the cervix. If the cervix is difficult to find visually, a bimanual exam can help ascertain its location.

Once the cervix is identified, characteristics of the cervix should be noted, including its position, size, color, and the presence of any lesions, ulcers, discharge, or blood. Any necessary samples are taken at this time. Purulent discharge suggests an infection, and samples should be collected for testing. Masses concerning for malignancy should be further evaluated with colposcopy and biopsied. If the patient is pregnant, the clinician should also note whether the external os appears open or closed and whether any protruding tissue is visible. Any foreign bodies should be noted and removed.

To remove the speculum, the clinician releases the blades while starting to slowly withdraw the speculum to avoid pinching the cervix and vaginal walls. The speculum should be withdrawn in a slightly open position to allow the clinician to examine the vaginal wall for any irregularities, including inflammation, discharge, ulcers, or masses. The speculum should be closed as it is withdrawn from the vaginal introitus.

Bimanual Examination

Lubrication is applied to the index and middle fingers of the examiner's dominant hand, which are then gently inserted into the vagina. Similar to the insertion of the speculum, pressure should be directed posteriorly. The thumb should be abducted, and care should be taken to avoid pressing the thumb directly into the urethral meatus or clitoris; the fourth and fifth fingers are flexed into the examiner's palm. The nondominant hand is placed on the lower abdomen in the suprapubic region.

With the internal hand, the cervix is located and moved slightly, allowing the examiner to assess its position, consistency, mobility, cervical motion tenderness, and any lesions or nodularity. If the patient has an IUD in place, the presence of palpable strings should also be noted. It may be necessary to push down and inferiorly with the nondominant hand on the abdomen to push the cervix closer to the internal fingers.

Next, the internal fingers should move beneath the cervix and elevate the uterus while the abdominal hand presses down and inward, allowing the uterus to be grasped between the examiner's 2 hands. This allows the examiner to assess the uterus's size, shape, mobility, and tenderness, which may suggest a diagnosis. For example, an enlarged uterus with irregular fundal contours suggests uterine leiomyomas, whereas tenderness is more consistent with inflammation (eg, from endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease [PID]). Poor mobility suggests pelvic adhesive disease, which can be seen with endometriosis, a prior history of PID, and gynecologic malignancies. If the uterus is retroverted, it may be better assessed with a rectovaginal exam.

Finally, the adnexa should be palpated by moving the pelvic hand to the anterior lateral fornix and the abdominal hand to the corresponding lower abdominal quadrant. The abdominal hand should press in and downward, attempting to sweep the adnexal structures into the pelvic hand. The adnexa's size, shape, mobility, and tenderness should be identified, and that process should be repeated on the opposite side. Note that the ovaries are often difficult to palpate in women who are obese, postmenopausal, or tense. After palpating the adnexa, the internal fingers are gently withdrawn.

Rectovaginal Examination

A rectovaginal examination may be necessary to examine the rectovaginal septum, uterosacral ligaments, posterior cul-de-sac, adnexa, or a retroverted uterus. Since this step is often omitted, the plan to insert a rectal finger should be explicitly discussed with the patient before this step is performed. The presence of hemorrhoids, polyps, and abnormal lesions should be noted. The lubricated third digit is slowly inserted into the rectum while the patient bears down to allow for relaxation of the sphincter, minimizing discomfort. At the same time, the index finger is inserted into the vagina, and both fingers are used to feel the rectovaginal septum and internal organs in the posterior pelvis. Downward pressure from an abdominal hand can help move the pelvic structures closer to the internal fingers.

Complications

Although uncommon, complications can occur during a gynecologic exam.

In women with atrophic vaginitis, the speculum exam may be very painful and may cause mucosal tearing; liberal lubrication and a narrow speculum are recommended for these patients. Additionally, a pelvic exam may exacerbate symptoms in patients with chronic pelvic pain.

In patients with a history of sexual trauma, a pelvic examination may trigger anxiety or posttraumatic stress disorder. Excellent communication and obtaining consent before and during each part of the exam can help alleviate anxiety in some patients. Mental health counseling, anxiolytics, and various modifications to the exam can also be offered, such as self-insertion of the speculum, offering the option of a female-only clinical team, or having a friend or family member in the room for support. It should be stressed that the examiner can stop the exam at any time the patient requests.[18]

Clinical Significance

The gynecologic exam allows clinicians to assess vulvar, vaginal, uterine, adnexal, and pelvic pathology. The exam is a critical component of the evaluation for numerous obstetric and gynecologic complaints, including abnormal bleeding, discharge, pain, masses, lesions, incontinence, prolapse, and more.[17] Many specimens can be collected for diagnostic or screening tests, including STI testing, cervical cancer screening, microscopic evaluation of discharge, and biopsies.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The gynecologic examination must be performed with a patient-centered approach, including good comprehensive clinical skills and proper technique to avoid iatrogenic effects, such as pain, traumatization, and anxiety. Communication skills are vital for explaining procedures and addressing patient concerns. Physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners should be familiar with exam techniques, and nurses and medical technicians should be comfortable providing support to both the physician and patient and serving as a patient advocate during the exam.[17]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Uterine Tubal Anatomy and Ligaments. Shown in this illustration are anatomical structures surrounding the uterus and fallopian or uterine tubes, including the mesosalpinx, mesovarium, ovarian artery, ovarian vein, suspensory ligament, uterine tube, ovary, broad ligament, round ligament, ovarian ligament, cardinal ligament, uterosacral ligament, and vagina.

Contributed by B Palmer

References

Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Harris R, Starkey M, Denberg TD, Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Screening pelvic examination in adult women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2014 Jul 1:161(1):67-72. doi: 10.7326/M14-0701. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24979451]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePauls RN. Anatomy of the clitoris and the female sexual response. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2015 Apr:28(3):376-84. doi: 10.1002/ca.22524. Epub 2015 Mar 2 [PubMed PMID: 25727497]

Raizada V, Mittal RK. Pelvic floor anatomy and applied physiology. Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2008 Sep:37(3):493-509, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.06.003. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18793993]

Cohen Sacher B. The Normal Vulva, Vulvar Examination, and Evaluation Tools. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Sep:58(3):442-52. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000123. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26083130]

White M, Byrne H, Molphy Z, Flood K. How well do we truly understand clitoral anatomy? An Irish maternity hospital's perspective. The Australian & New Zealand journal of obstetrics & gynaecology. 2023 Oct 15:():. doi: 10.1111/ajo.13758. Epub 2023 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 37840188]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLonghurst GJ, Beni R, Jeong SR, Pianta M, Soper AL, Leitch P, De Witte G, Fisher L. Beyond the tip of the iceberg: A meta-analysis of the anatomy of the clitoris. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2024 Mar:37(2):233-252. doi: 10.1002/ca.24113. Epub 2023 Sep 29 [PubMed PMID: 37775965]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceEvans D, Goldstein S, Loewy A, Altman AD. No. 385-Indications for Pelvic Examination. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada : JOGC = Journal d'obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada : JOGC. 2019 Aug:41(8):1221-1234. doi: 10.1016/j.jogc.2018.12.007. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31331610]

Meyer R, Rottenstreich A, Mohr-Sasson A, Dori-Dayan N, Toren A, Levin G. Tampon loss - management among adolescents and adult women. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology : the journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2021 Feb:41(2):275-278. doi: 10.1080/01443615.2020.1755631. Epub 2020 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 32500774]

Maheut C, Vernet T, Le Boité H, Fernandez H, Capmas P. Correlation between clinical examination and perineal ultrasound in women treated for pelvic organ prolapse. Journal of gynecology obstetrics and human reproduction. 2023 Nov:52(9):102650. doi: 10.1016/j.jogoh.2023.102650. Epub 2023 Aug 22 [PubMed PMID: 37619710]

Norby N, Sabu P, Locklear T, Shvygin A, Lara-Torre E, Johnson IM. Incidence of Abnormal Findings During Pelvic Examinations in Women Aged 21-35 Years. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2024 Jan 1:143(1):6-8. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000005445. Epub 2023 Nov 9 [PubMed PMID: 37944138]

. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 754: The Utility of and Indications for Routine Pelvic Examination. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Oct:132(4):e174-e180. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002895. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30247363]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUS Preventive Services Task Force, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Barry MJ, Davidson KW, Doubeni CA, Epling JW Jr, García FA, Kemper AR, Krist AH, Kurth AE, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Phillips WR, Phipps MG, Silverstein M, Simon M, Siu AL, Tseng CW. Screening for Gynecologic Conditions With Pelvic Examination: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2017 Mar 7:317(9):947-953. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0807. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28267862]

Buys SS, Partridge E, Black A, Johnson CC, Lamerato L, Isaacs C, Reding DJ, Greenlee RT, Yokochi LA, Kessel B, Crawford ED, Church TR, Andriole GL, Weissfeld JL, Fouad MN, Chia D, O'Brien B, Ragard LR, Clapp JD, Rathmell JM, Riley TL, Hartge P, Pinsky PF, Zhu CS, Izmirlian G, Kramer BS, Miller AB, Xu JL, Prorok PC, Gohagan JK, Berg CD, PLCO Project Team. Effect of screening on ovarian cancer mortality: the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2011 Jun 8:305(22):2295-303. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.766. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21642681]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFan T, Amobi A. Screening for Gynecologic Conditions with Pelvic Examination. American family physician. 2017 Aug 15:96(4):253-254 [PubMed PMID: 28925672]

Norrell LL, Kuppermann M, Moghadassi MN, Sawaya GF. Women's beliefs about the purpose and value of routine pelvic examinations. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2017 Jul:217(1):86.e1-86.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2016.12.031. Epub 2016 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 28040449]

. Over-the-Counter Access to Hormonal Contraception: ACOG Committee Opinion, Number 788. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2019 Oct:134(4):e96-e105. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003473. Epub [PubMed PMID: 31568364]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWilliams AA, Williams M. A guide to performing pelvic speculum exams: a patient-centered approach to reducing iatrogenic effects. Teaching and learning in medicine. 2013:25(4):383-91. doi: 10.1080/10401334.2013.827969. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24112210]

Bates CK, Carroll N, Potter J. The challenging pelvic examination. Journal of general internal medicine. 2011 Jun:26(6):651-7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1610-8. Epub 2011 Jan 12 [PubMed PMID: 21225474]

Santen SA, Seth N, Hemphill RR, Wrenn KD. Chaperones for rectal and genital examinations in the emergency department: what do patients and physicians want? Southern medical journal. 2008 Jan:101(1):24-8. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e31815d3df4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18176287]