Introduction

Panniculitis encompasses a wide variety of skin diseases characterized primarily by inflammation of the subcutaneous fat. The condition is not an extension of dermatoses of the dermis, such as morphea, or fascia, such as eosinophilic fasciitis, into the subcutis.[1] Panniculitis typically presents clinically with tender subcutaneous erythematous nodules or plaques, most often on the lower extremities. Additional features, such as sclerosis, ulceration, or atrophy, may also be noted depending on the subtype.[2]

Panniculitis encompasses a heterogeneous group of rare disorders that may present with similar clinical features. Therefore, diagnosis can be difficult without histopathological correlation. Combining patient history, physical examination, and histopathological examination of a biopsy specimen is often necessary to diagnose panniculitides accurately and separate them from bruising and neoplasia.[3]

Issues of Concern

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Issues of Concern

Panniculitis can be challenging to diagnose because the presentation is often nonspecific, and laboratory findings alone can lead to misdiagnosis.[4] Panniculitis encompasses several subtypes requiring histopathologic evaluation due to their clinical similarities. Diagnostic challenges can arise from biopsy specimens with insufficient subcutaneous fat or are taken too late, producing nonspecific findings.[5]

A deep incisional biopsy should be performed after cleansing the skin surface with alcohol, which is allowed to evaporate. Punch biopsy specimens may fracture and leave valuable evidence of inflammation or necrosis. An electric rotary power punch may overcome this limitation.

If a punch biopsy is performed, it should be at least 6 mm in diameter to accommodate culture and hematoxylin and eosin staining. Including areas of necrosis in the biopsy is important for facilitating culture and special stains, such as fungal and acid-fast bacillus stains.[6]

Causes

Panniculitis is a broad term for conditions resulting from inflammation of the subcutaneous fat, which can be due to infection, trauma, enzymatic destruction, malignancy, or autoimmune factors. Achieving a precise diagnosis often requires a stepwise approach, including appropriate biopsies of deeper skin sections and thorough clinicopathologic correlation.[7][8] The condition has no universally accepted classification. However, many pathologists use the following stepwise approach:

- Determine whether the inflammation predominantly affects the fat lobules, such as the lobular, the septa between the lobules, such as the septal, or both. Most panniculitides have a mixture of both septal and lobular inflammation.

- Assess for vasculitis and, if present, evaluate the size and type of blood vessels involved, such as venules or arterioles of small vessels and veins and arteries of large vessels.

- Identify the type of cells in the inflammatory infiltrate, such as neutrophils, lymphocytes, histiocytes, and plasma cells.

- Recognize any additional histopathological features that may help lead to a final diagnosis, such as the presence or type of necrosis, sclerosis, or foreign bodies.

Although not necessary for diagnosis, special stains, polarized light microscopy, and culture may help further characterize the lesion. Polarized light microscopy helps rule out foreign material, whereas culture may identify inciting microbes such as bacteria or fungi.

Anatomical Pathology

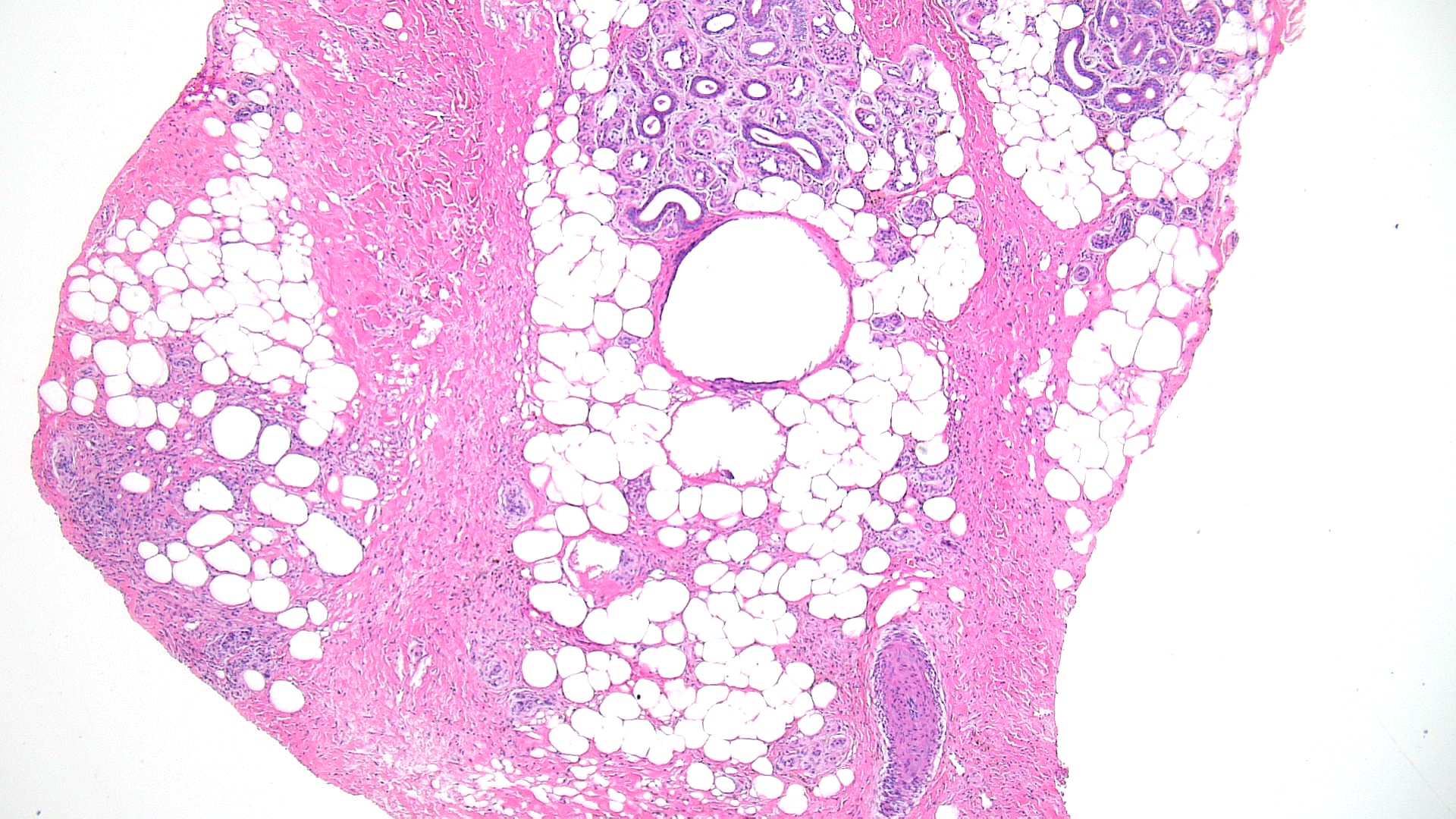

Subcutaneous fat is organized into lobules and septa. The lobules are made up of energy-rich adipocytes, which are separated by thin septa composed of collagen and reticulin connective tissue.[9] The septa contain blood vessels, lymphatics, and nerves. Each lobule is supplied by its respective artery or arteriole, representing a terminal blood vessel where damage can lead to inflammation and necrosis of the adipocytes. Adipocytes appear empty on the hematoxylin-eosin staining with a signet-ring morphology. The nucleus is flattened and displaced to the side of the cell through a large, fat-containing vacuole.

Morphology

Histopathologically, panniculitis can be classified into predominantly septal or lobular panniculitis with or without vasculitis. The classification informs the treatment choice, helps predict the disease course and treatment response, and determines the need for additional interventions.

Predominantly Septal Panniculitides Without Vasculitis

Predominantly septal panniculitides without vasculitis are typically caused by damage to small venules. This category includes:

Erythema nodosum: Erythema nodosum is widely considered the most common form of panniculitis and is the prototype for septal panniculitis without vasculitis. The condition presents as an acute nodular eruption on the lower legs, possibly associated with systemic symptoms. The lesions are typically transient and can be associated with underlying infections or systemic conditions, including sarcoidosis; Behcet disease; celiac disease; Sweet syndrome; inflammatory bowel disease; reactions to drugs such as isotretinoin, sulfonamides, and ciprofloxacin; infection with bacteria such as staphylococcal and streptococcal infections; fungi such as dermatophyte and sporotrichosis; viruses such as HIV; mycobacteria; and malignancy, such as leukemia.

Histology shows thickened subcutaneous fat septa with inflammatory infiltrates of varying morphology, depending on the age of the lesion (see Image. Erythema Nodosum, Low Power). Early lesions present with edema, hemorrhage, neutrophils, and Miescher radial microgranulomas. These microgranulomas are the histopathological hallmark of erythema nodosum, consisting of small histiocytes aggregated around a central star-shaped cleft (see Image. Erythema Nodosum, High Power).[10][11] Fibrosis, lymphocytes, and multinucleated giant cells predominate in later stages.

Deep morphea/scleroderma: Histopathology reveals septal thickening with collagen bundles replacing subcutaneous fat surrounding eccrine ducts. In the early acute phase, a mixture of inflammatory lymphocytes and plasma cells may be present. In the later chronic phase, fibrosis and hyalinization are predominant. Granulomatous infiltrates are absent.[12] Systemic sclerosis exhibits this pathology.

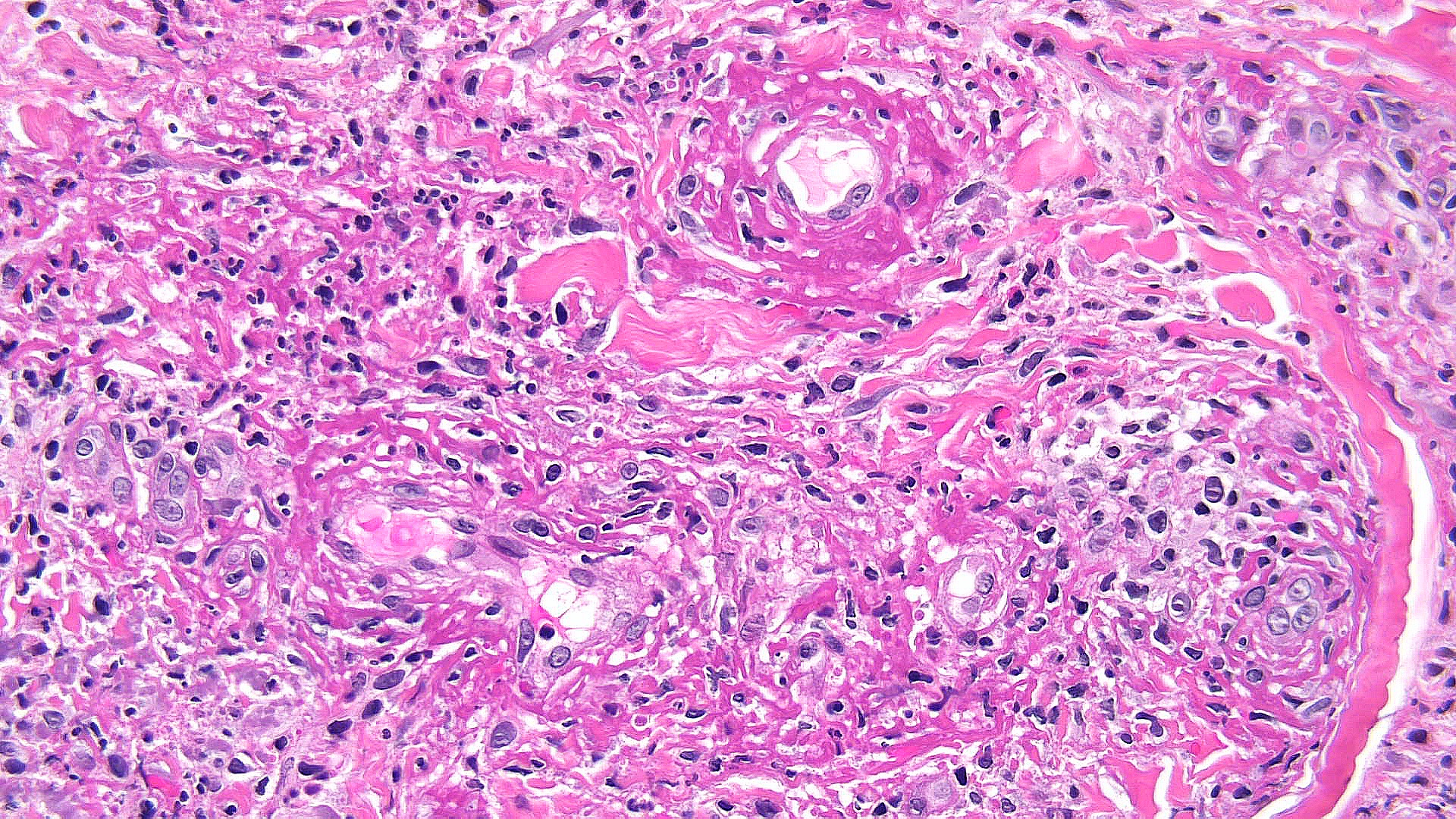

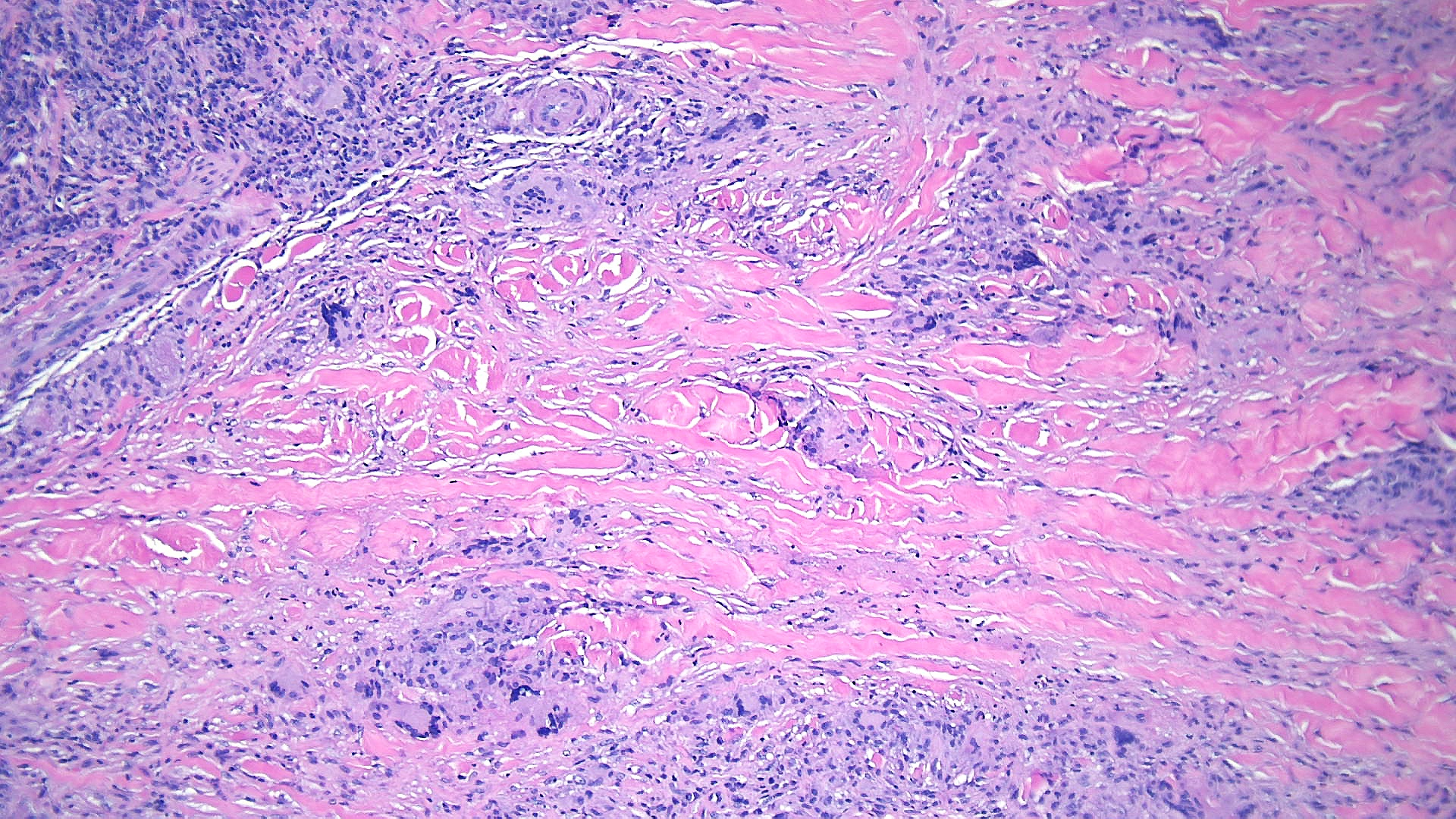

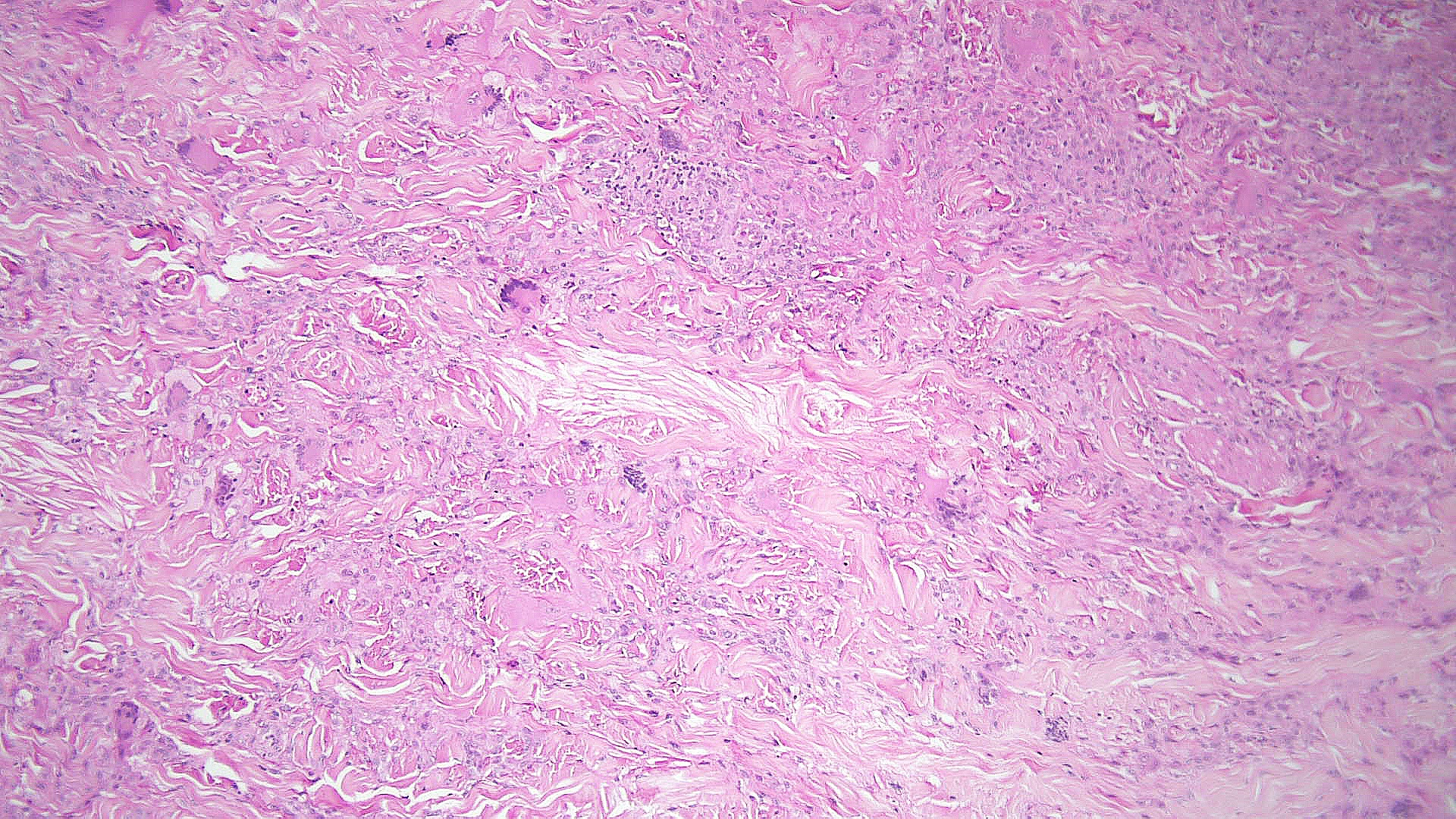

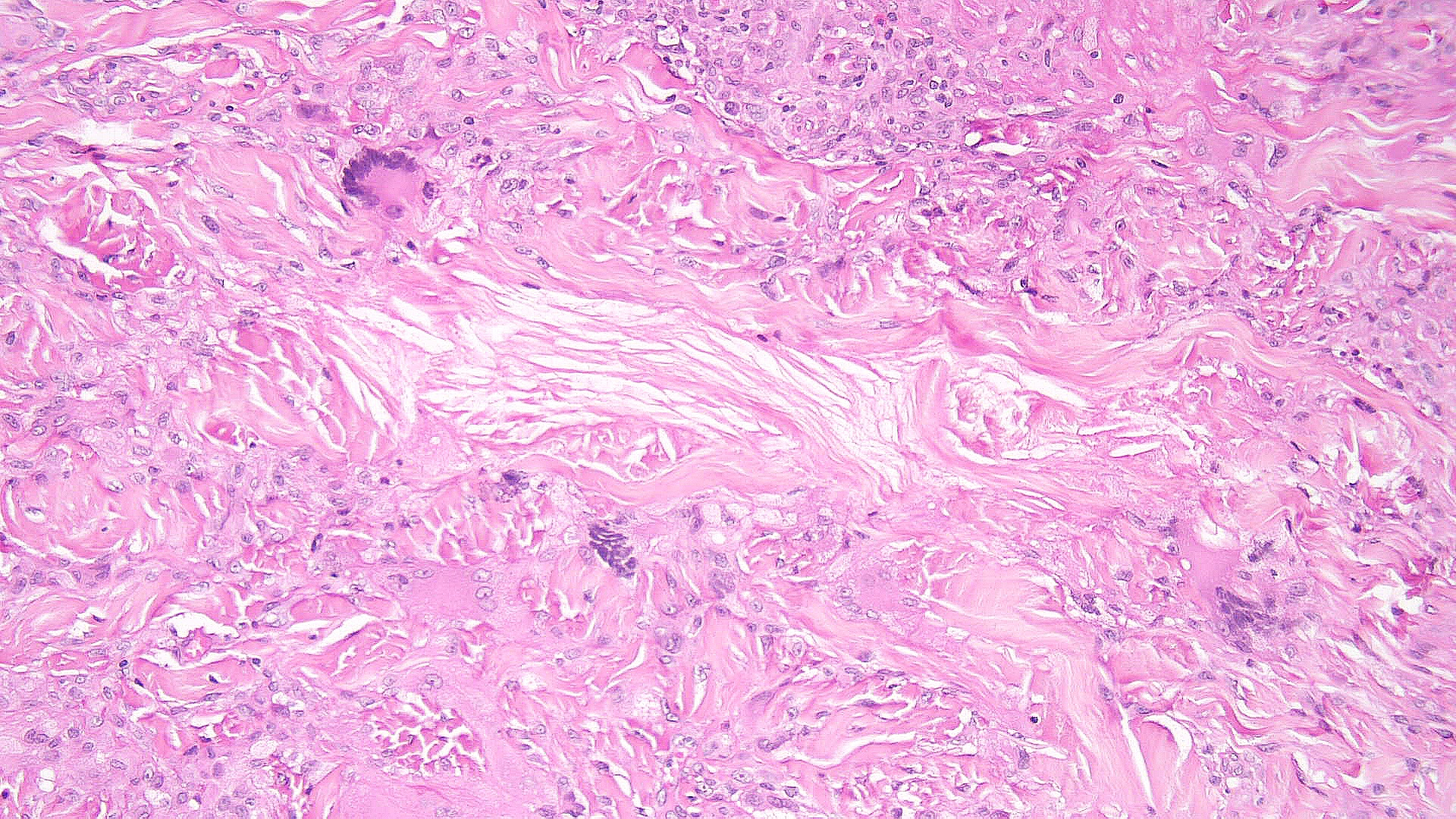

Necrobiotic xanthogranuloma: Histopathology typically shows large areas of necrobiosis alternating with granulomatous inflammation, including foamy histiocytes, cholesterol clefts, and Touton giant cells, which are characterized by a wreath of nuclei surrounded by a peripheral rim of foamy cytoplasm (see Images. Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma Pathology, Low Power and Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma Pathology, High Power).[13]

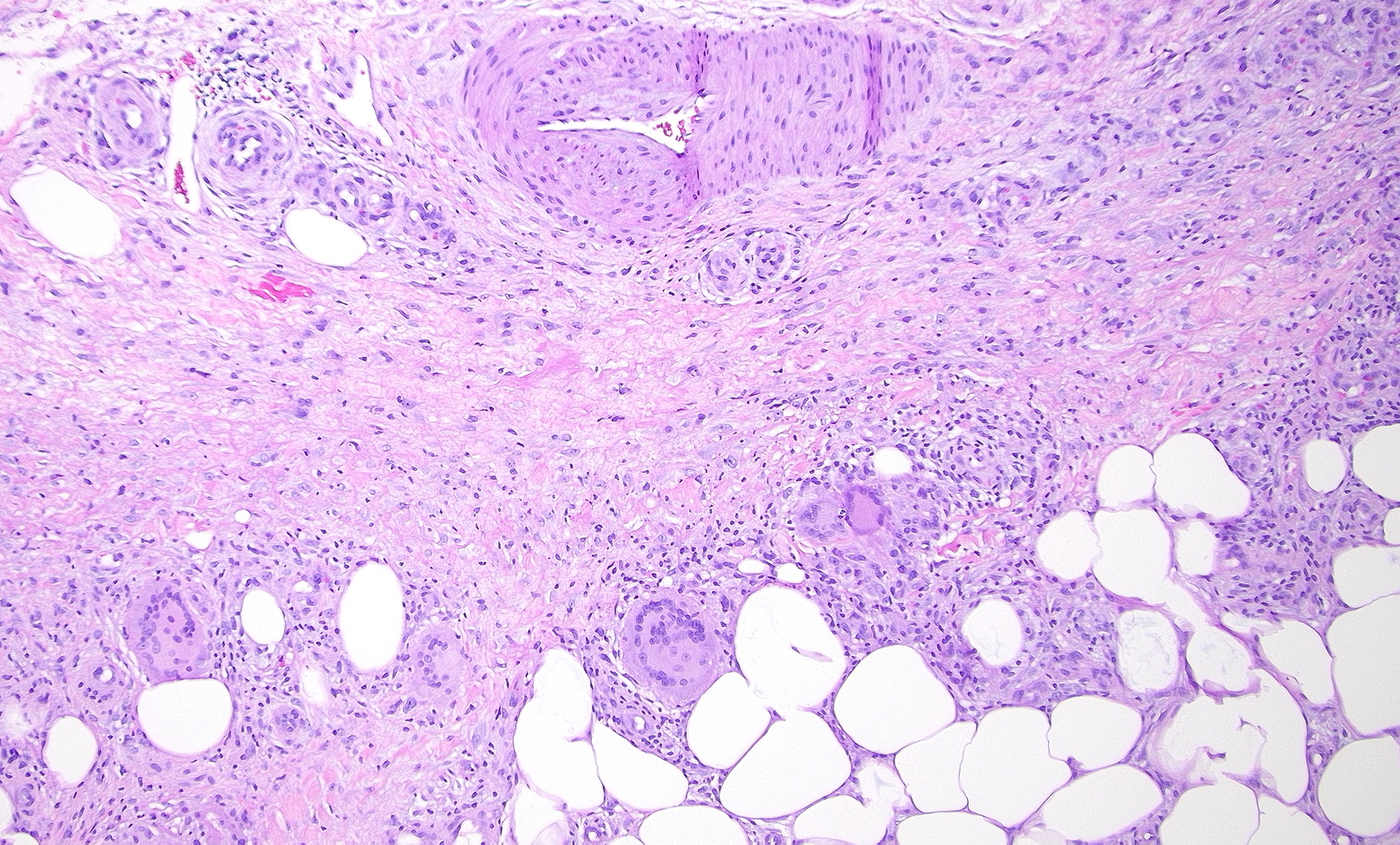

Subcutaneous granuloma annulare: Subcutaneous granuloma annulare histopathology is characterized by infiltrates of palisading histiocytes surrounding mucin and basophilic degeneration of collagen bundles (see Images. Granuloma Annulare, Low Power and Granuloma Annulare, High Power).[14] The presence of mucin is considered a hallmark of subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Multinucleated giant cells, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and neutrophils may also be observed infiltrating the dermis.[15]

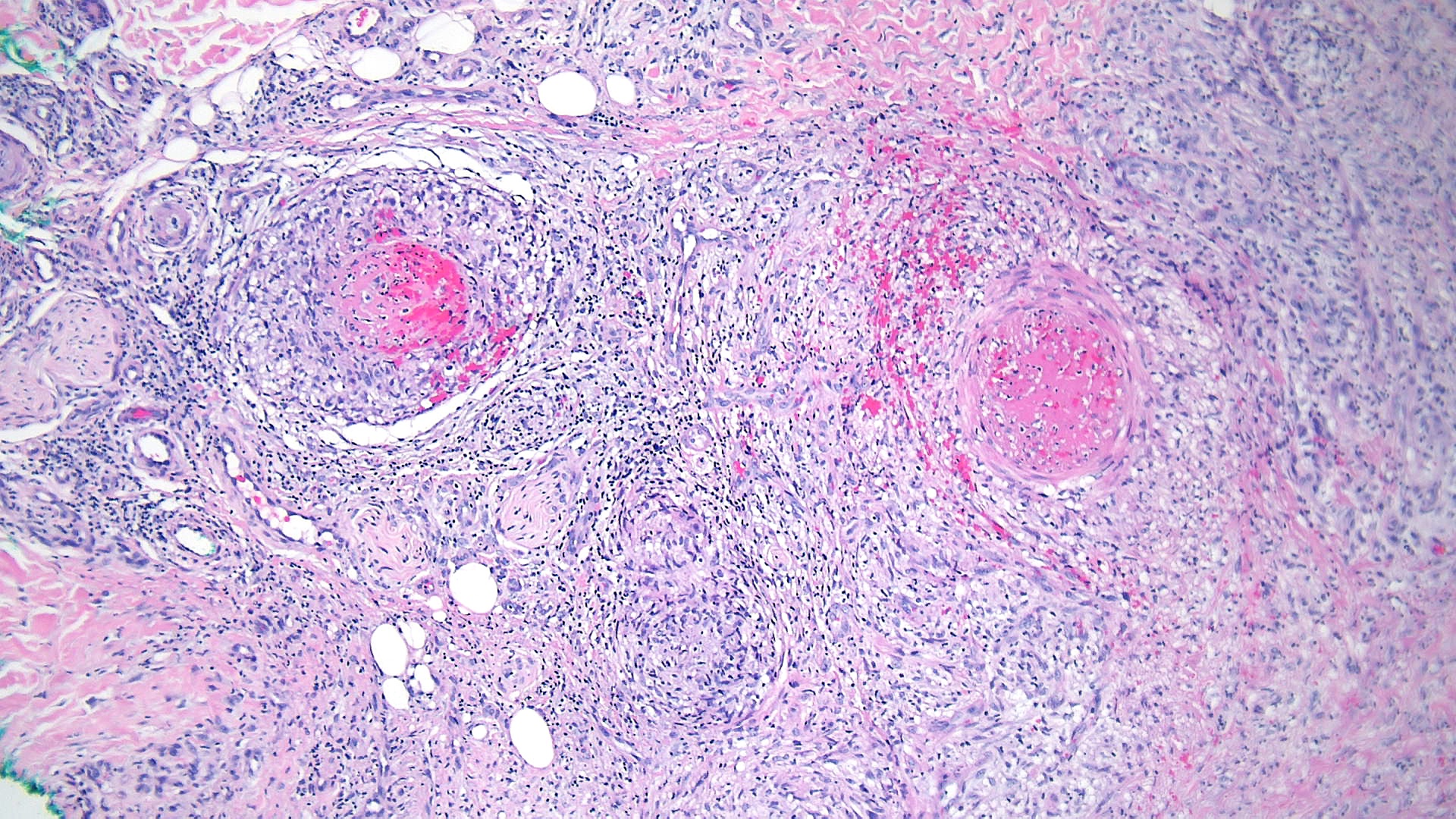

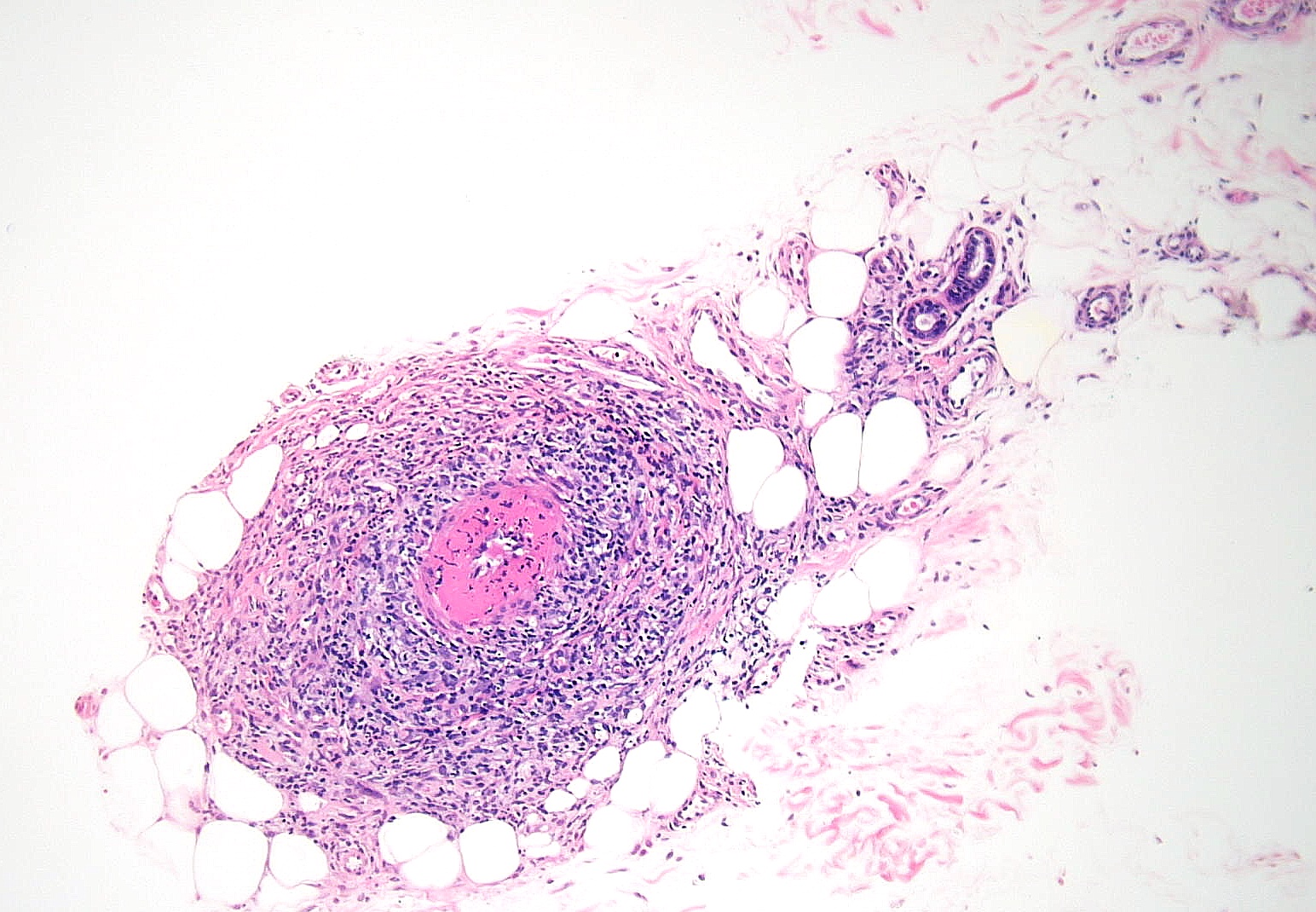

Rheumatoid nodule: Rheumatoid nodules appear in approximately 20% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Histopathology shows large areas of necrobiosis with eosinophilic material composed of fibrin, surrounded by palisading histiocytes within the dermis and subcutaneous fat (see Image. Rheumatoid Nodule Pathology).

Necrobiosis lipoidica: Histopathology typically shows layers of granulomatous inflammation, occasional multinucleated giant cells, histiocytes, plasma cells, and alternating zones of degenerated collagen without mucin (see Images. Low-Power Pathological Findings of Necrobiosis Lipoidica: Skin Biopsy and High-Power Pathological Findings of Necrobiosis Lipoidica: Skin Biopsy).[16]

Predominantly Septal Panniculitides With Vasculitis

Predominantly septal panniculitides with vasculitis may arise from etiologies, including malignancies and autoimmunity. This set of conditions includes the following:

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis: Histopathology of leukocytoclastic vasculitis reveals septal inflammation with necrosis of postcapillary venule walls, evident as necrotic endothelial cells, neutrophils, nuclear dust, and fibrin deposition in the vessel walls (see Image. Leukocytoclastic Vasculitis Pathology).

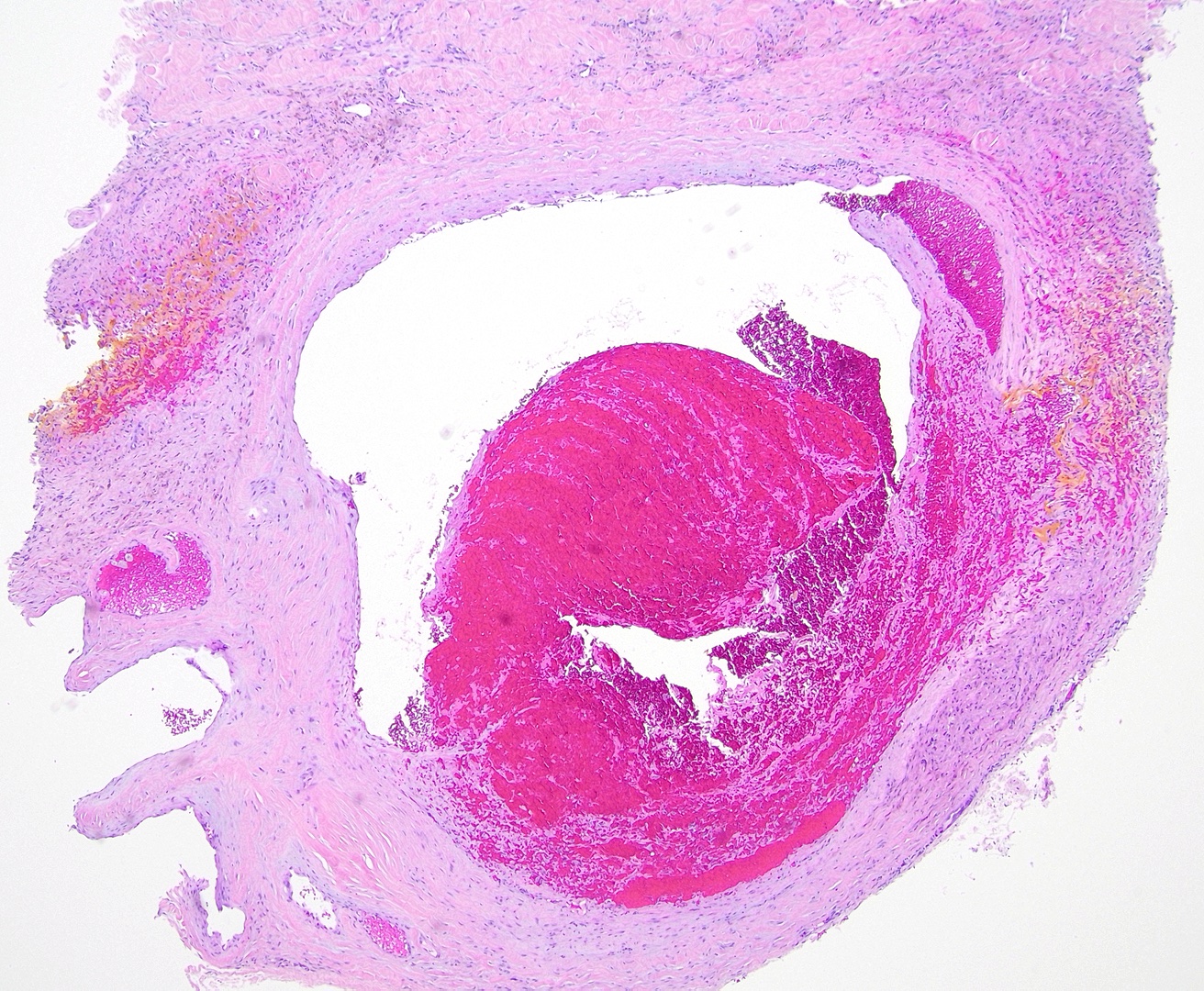

Superficial thrombophlebitis: Superficial thrombophlebitis predominantly affects larger veins in the deeper dermis and subcutaneous fat and presents with cord-like induration. Therefore, histopathology typically reveals vasculitis and thrombosis occluding the lamina (see Image. Thrombophlebitis Pathology).[17] The predominant inflammatory cell type in earlier lesions is mainly composed of neutrophils. Later stages may show lymphocytes, histiocytes, and giant cells. This condition is associated with pancreatic carcinoma, Behcet syndrome, and Buerger disease.

Cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa: Histopathology of cutaneous polyarteritis nodosa reveals the involvement of the septa's small-to-medium–sized arteries and arterioles. Lesions show prominent fibrinoid necrosis and fibrin deposition, with the destruction of the tunica intima (see Image. Polyarteritis Nodosa Pathology). Neutrophils make up most inflammatory cells in earlier stages. Lymphocytes and histiocytes later increase in proportion. This pathology is considered a benign polyarteritis nodosa unrelated to systemic vasculitis.

Other causes of septal panniculitis include factitial panniculitis, cellulitis, nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, hydroa vacciniforme, cytomegalovirus infection, microscopic polyangiitis, apomorphine infusion, cryoglobulinemia, Whipple disease, and α1-antitrypsin deficiency.

Predominantly Lobular Panniculitides Without Vasculitis

Conditions with predominantly lobular panniculitides without vasculitis arise from various causes. These conditions include the following:

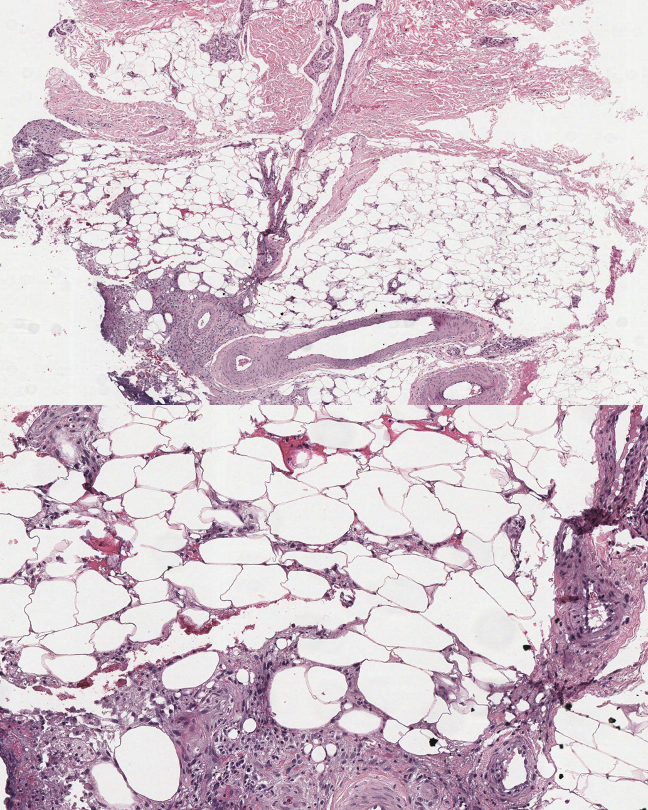

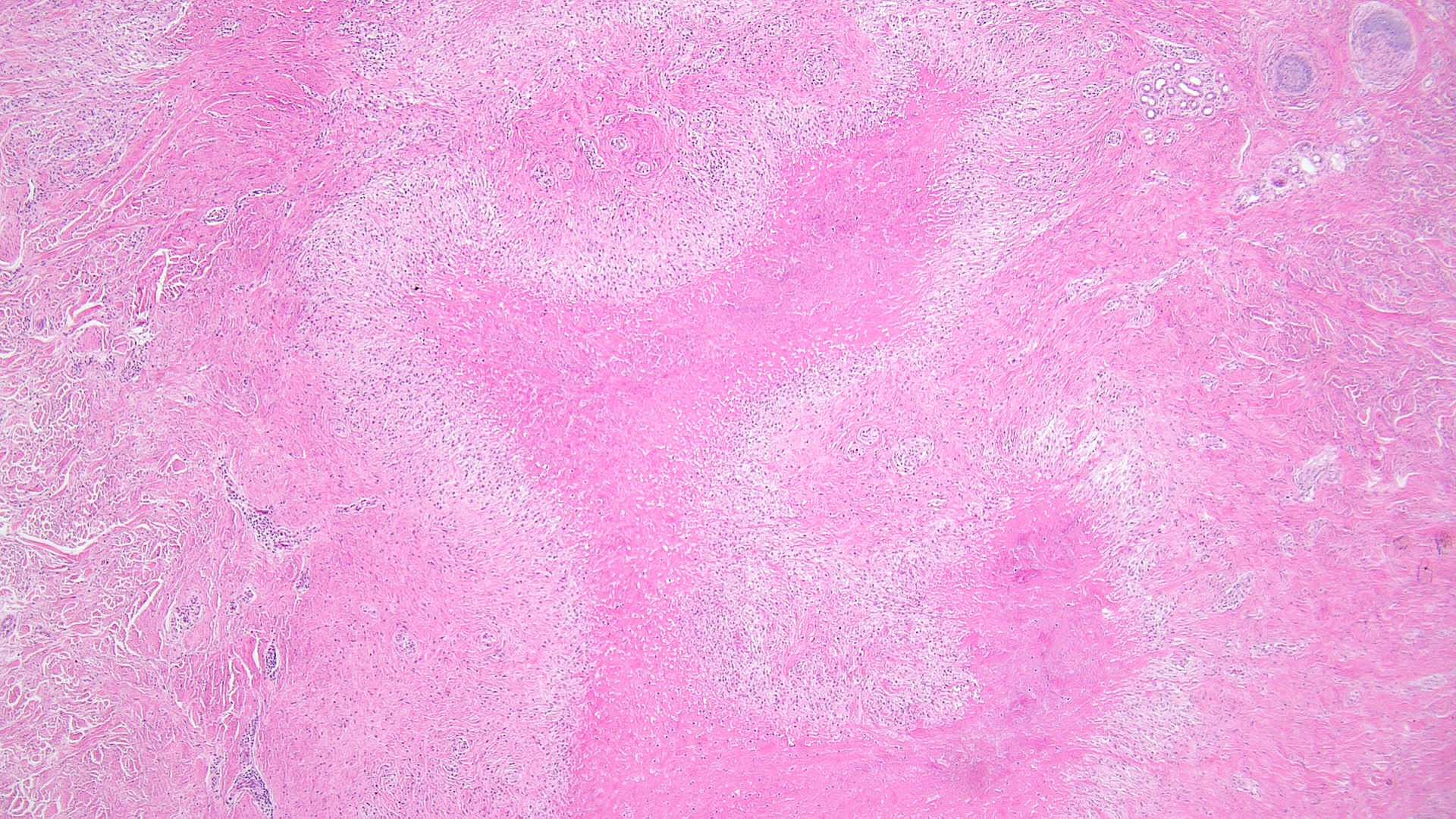

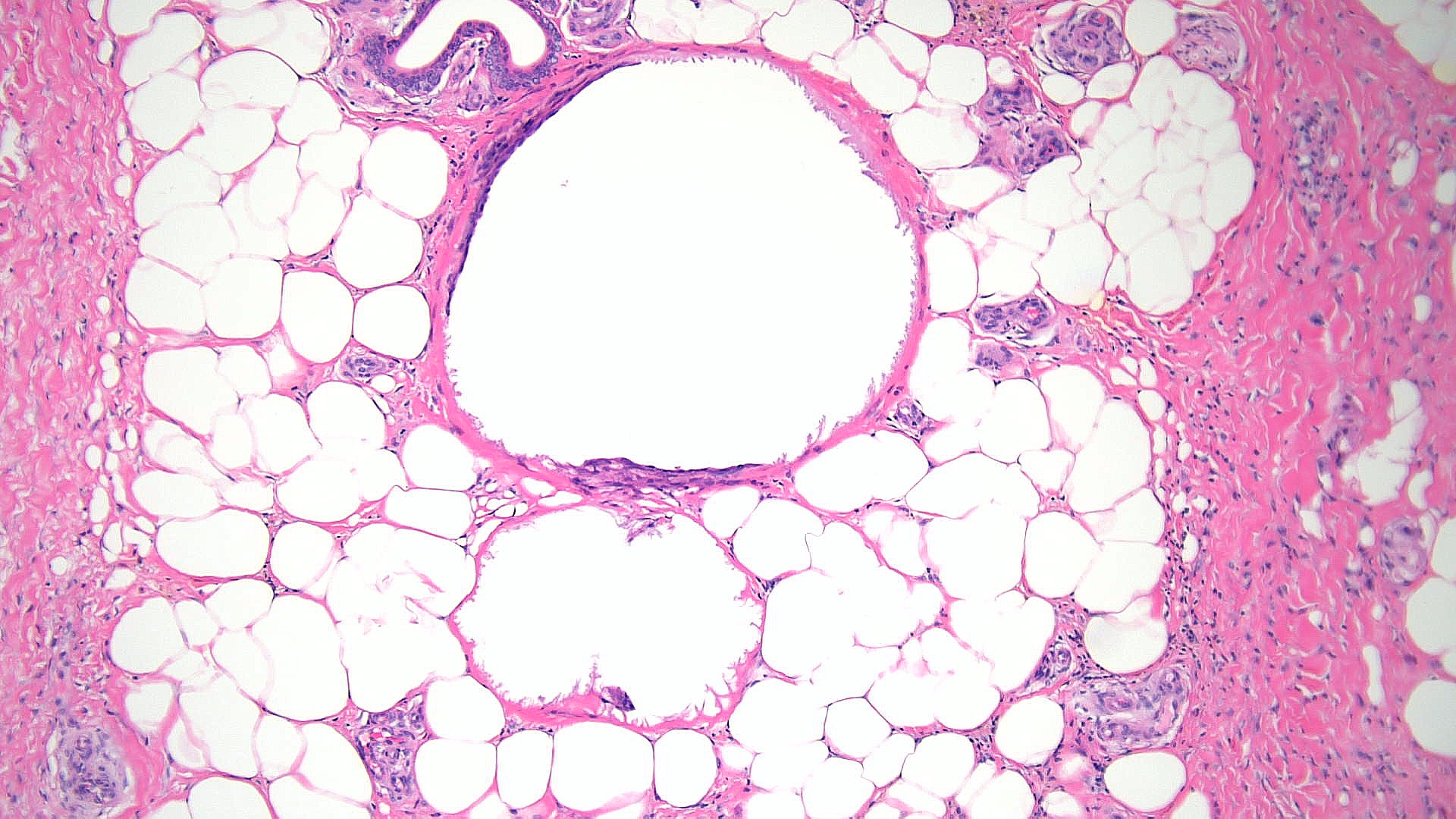

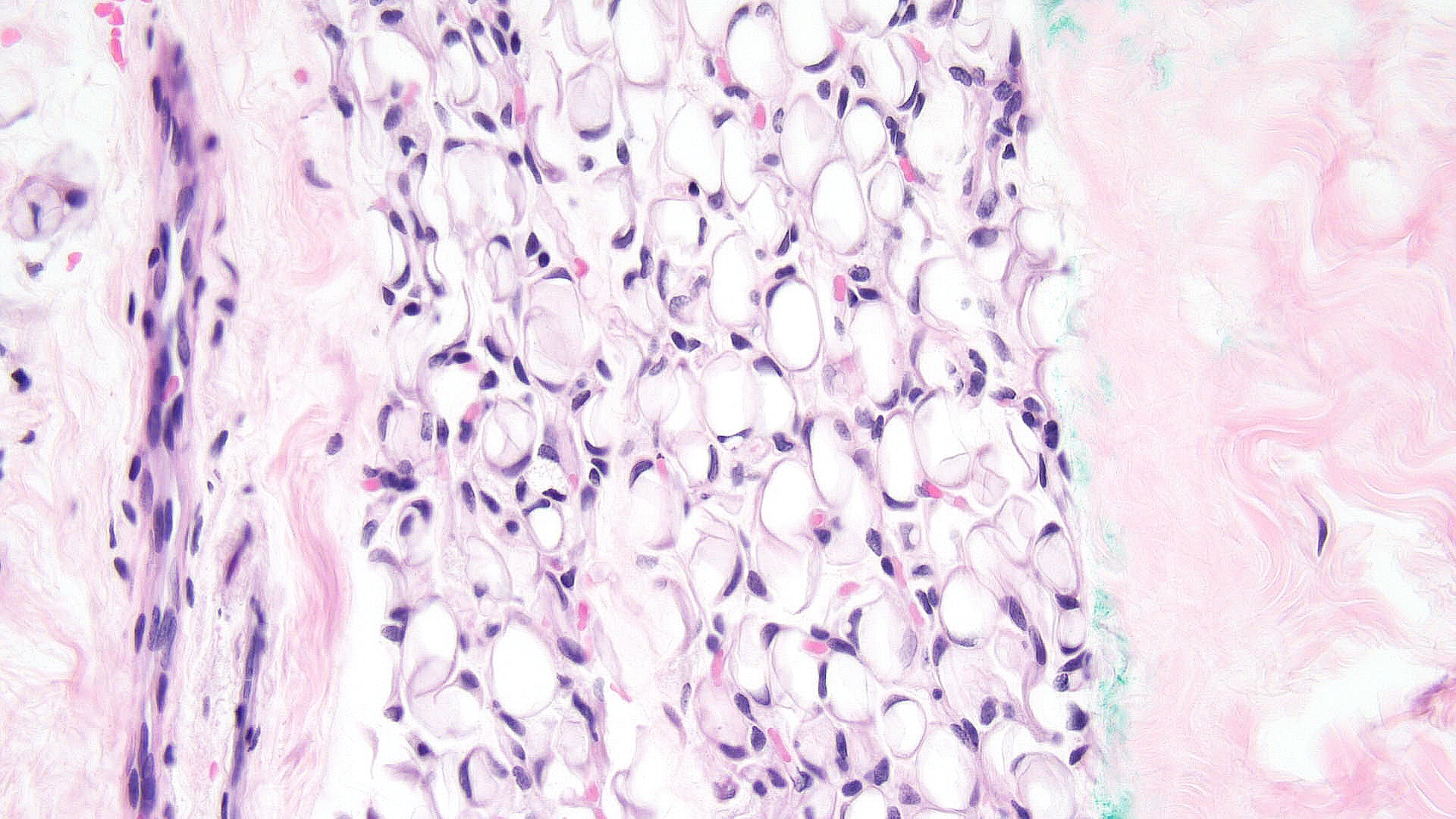

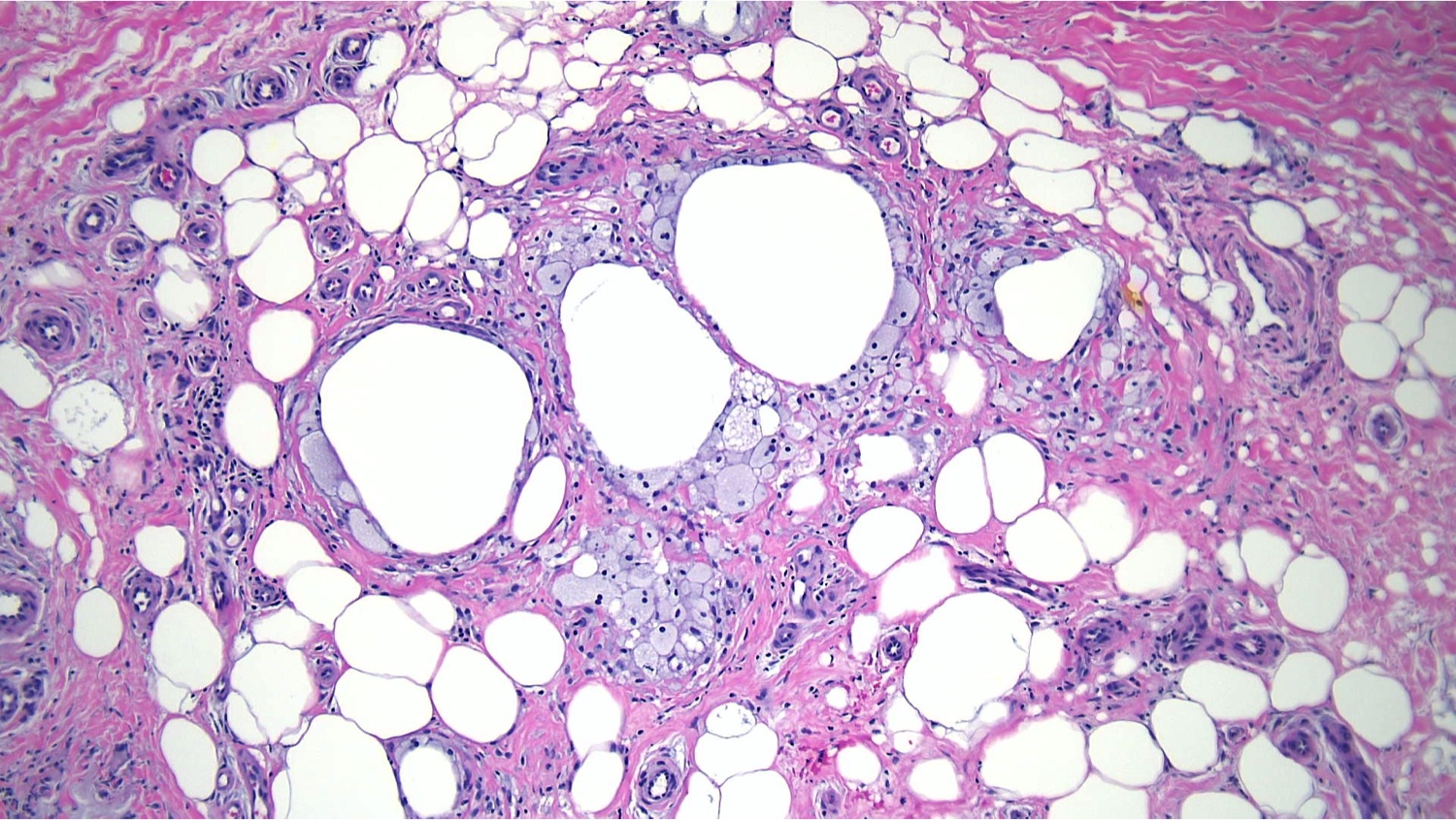

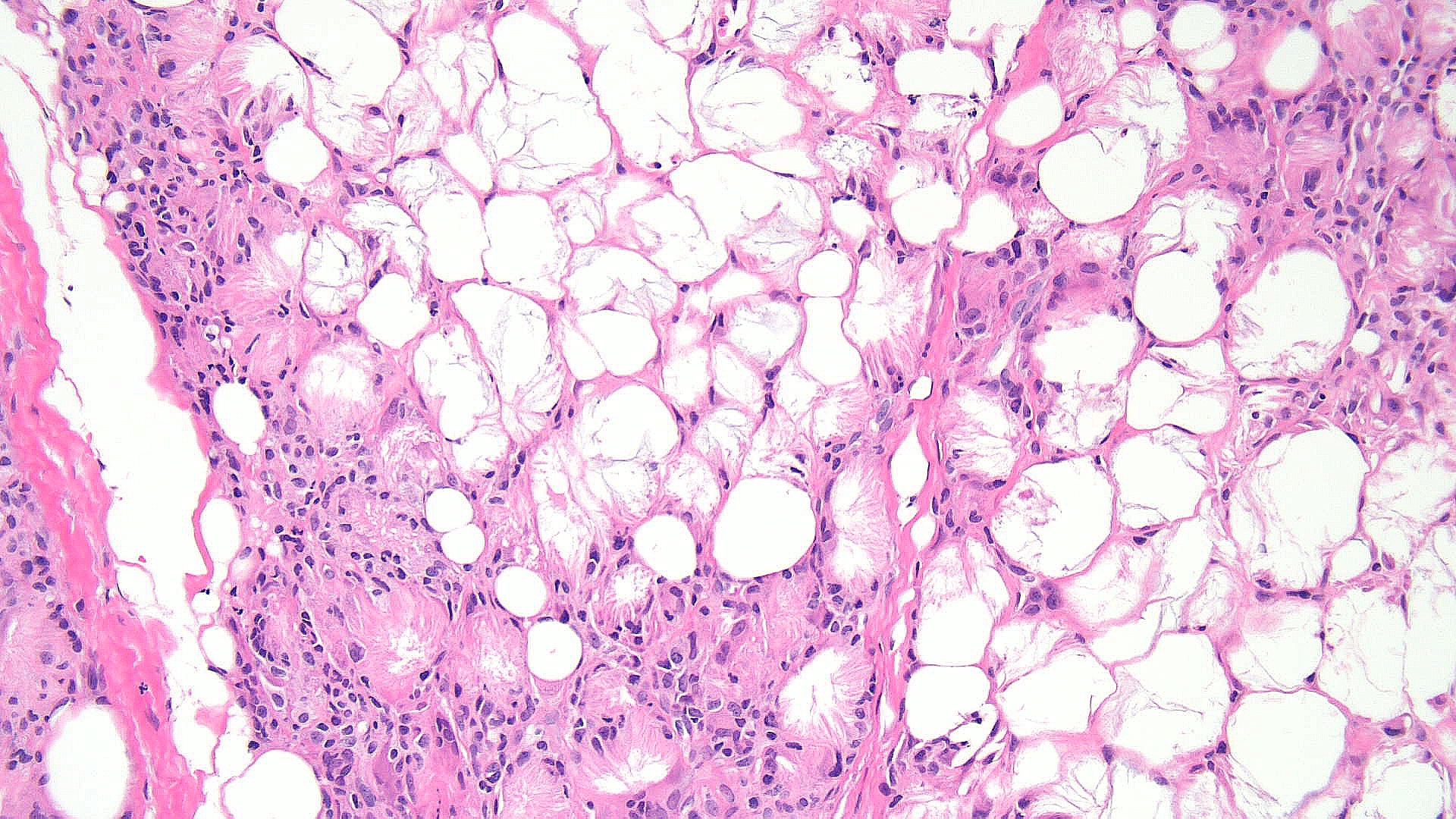

Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn is a self-resolving panniculitis affecting the thighs, cheeks, and buttocks of neonates. The condition is related to hypothermia and hypercalcemia. The presence of needle-shaped clefts within adipocytes is a hallmark histopathological finding (see Image. Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis of the Newborn, Low Power).[18][19] Subcutaneous fat necrosis shows a dense lymphocytic infiltrate (see Image. Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis of the Newborn, High Power).[20] Electron microscopy shows needle-shaped crystals in parallel and macrophages surrounding necrotic fat cells.[21]

Sclerema neonatorum: Sclerema neonatorum presents with waxy, dry skin and is considered a diffuse form of subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn. However, this condition is less common, likely due to improved neonatal care.[22] Histopathology is similar to subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn with minimal inflammation, including the absence of histiocytes, and no calcification.[23]

Post-steroid panniculitis: Unlike subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn, post-steroid panniculitis has less inflammation and fewer needle-shaped clefts. By comparison, inflammation is scarce or absent in sclerema neonatorum (see Image. Post-steroid Panniculitis Pathology).

Cold panniculitis: Cold panniculitis can present with indurated plaques in severely cold conditions, typically in younger children. Histopathology reveals lymphocytes and histiocytes in the fat lobules, with marked edema and superficial and deep perivascular dermal infiltrate. The most significant changes are observed at the dermis-subcutis junction. This condition can overlap with deep perniosis in its presentation.

α1-Antitrypsin deficiency: This condition is characterized by low serum levels of α1-antitrypsin, most notably resulting in tender lesions that ulcerate with an oily discharge following an inciting event, such as trauma.[24][25] The acute phase presents with neutrophilic inflammation, followed by severe necrosis and destruction of fat lobules. A histopathological feature specific to this form of panniculitis includes the splaying of neutrophils between collagen bundles in the deep dermis in the early stages and floating fat in later stages.[26][27]

Cytophagic histiocytic panniculitis: Cytophagic histiocytic panniculitis presents as tender nodules with fever and liver dysfunction.[28] Histopathology shows fat necrosis and sheets of histiocytes phagocytosing erythrocytes, leukocytes, and nuclei, thus the term bean bag cells.[29] Some cases of cytophagic histiocytic panniculitis have been recharacterized as subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma.[30]

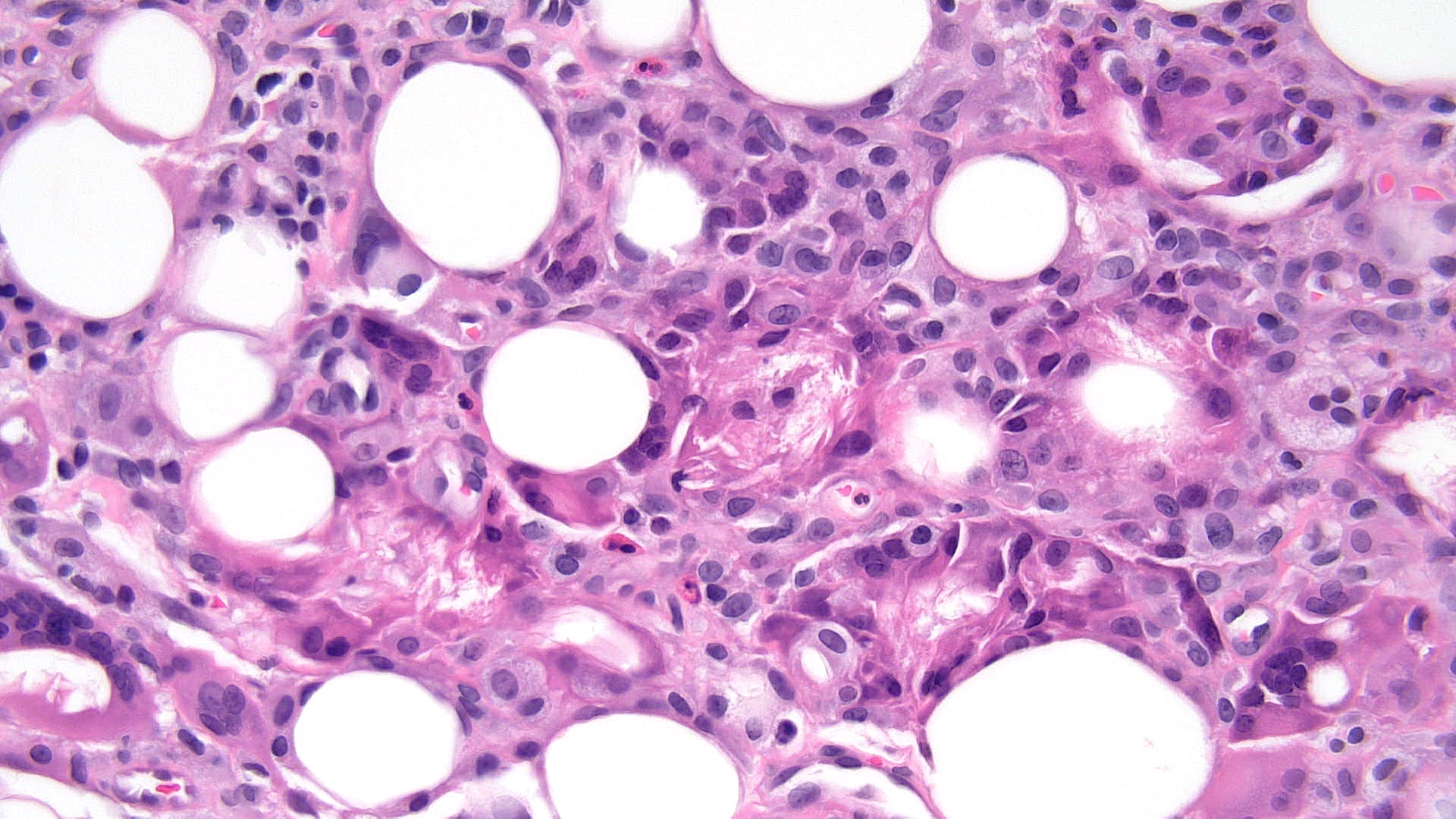

Pancreatic panniculitis: Pancreatic panniculitis typically presents as tender nodules on the lower extremities and is often associated with acute pancreatitis.[31] Histopathology of pancreatic panniculitis shows fat necrosis with saponification of adipocytes and a predominance of neutrophils (see Image. Pancreatic Panniculitis Pathology). In contrast to other types of lobular panniculitides showing necrosis as a late finding, pancreatic panniculitis may show necrosis in the acute phase. Furthermore, aggregates of ghost adipocytes, which have lost their nuclei and developed thick shadowy walls, may be present.[32]

Lupus panniculitis: Lupus panniculitis, also known as lupus profundus, presents typically on the trunk or proximal extremities as a complication of systemic lupus erythematosus or chronic cutaneous lupus erythematosus.[33] Histopathology of lupus panniculitis shows predominantly lobular panniculitis, although a mixed lobular-septal pattern may also be observed. Characteristic features include lymphoid follicles containing germinal centers without fat necrosis.[34] Collagen bundles of the septa are often hyaline and sclerotic, with an infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and plasma cells. Lymphocytic infiltrates may contain nuclear dust. Immunofluorescence studies often show a linear deposition of immunoglobulin M and complement C3 along the dermo-epidermal junction.[35]

Connective tissue panniculitis: Connective tissue panniculitis is a rare condition that typically presents on the lower limbs in patients with a low antinuclear antibody titer.[36] The condition may result from medications or lipoatrophy. Histopathology shows lobular panniculitis similar to erythema induratum without vessel changes.[37]

Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: Subcutaneous sarcoidosis presents with flesh-colored tender nodules on the extremities of middle-aged women. Histopathology is consistent with sarcoidosis, including naked lobular granulomas with fibrosis and some central necrosis.[38]

Lipodystrophy: Lipodystrophy may be secondary to morphea, lupus panniculitis, or repeated insulin or steroid injections. However, primary lipodystrophy includes total, partial, and localized lipodystrophy.[39] Total lipodystrophy may be acquired, as in Lawrence syndrome, associated with metabolic dysfunction, or congenital, as in Beradinelli–Seip syndrome.

Congenital total lipodystrophy is classified into 3 types. Type 1 is due to a mutation in the 1-acylglycerol-3-phosphate O-acyltransferase-2 gene. Type 2 is due to a mutation in the seipin gene. Type 3 is due to a mutation in the caveolin-1 gene.[40][41] Partial lipodystrophy presents with a loss of facial fat symmetrically and may be familial, such as Dunnigan type, or acquired, such as Barraquer-Simons disease. Of the acquired form, the Weir-Mitchell type does not include the lower extremity, whereas the Laignel-Lavastine type includes lower body hypertrophy.[42][43][44]

Unilateral variants of partial lipodystrophy associated with facial hemiatrophy comprise Parry-Romberg syndrome.[45] Familial partial lipodystrophy is an autosomal dominant partial lipodystrophy associated with mutations in the LMNA gene, which is implicated in progeria.[46] Localized lipodystrophy typically occurs in injection sites and may be confused with morphea. The condition presents with solitary annular areas of atrophy.[47][48][49] Lipedema presents with fat deposition, typically in the buttocks, and appears clinically similar to lymphedema.[50]

Histopathology of lipedema shows fatty hypertrophy with thickened fibrous septa. In contrast, the other lipodystrophy types may show small lipocytes and myxoid connective tissue or lobular panniculitis with lymphocytes, lipophages, and plasma cells, which may show vasculitis in the dermis or immunoreactants on vessels on direct immunofluorescence.[51][52] Lipodystrophy may be associated with HIV, such as HIV-associated lipodystrophy, or aging and obesity, such as gynoid lipodystrophy and cellulite. Some cases exhibit membranous change, such as membranous lipodystrophy, with pseudomembranous fat necrosis.[53][54]

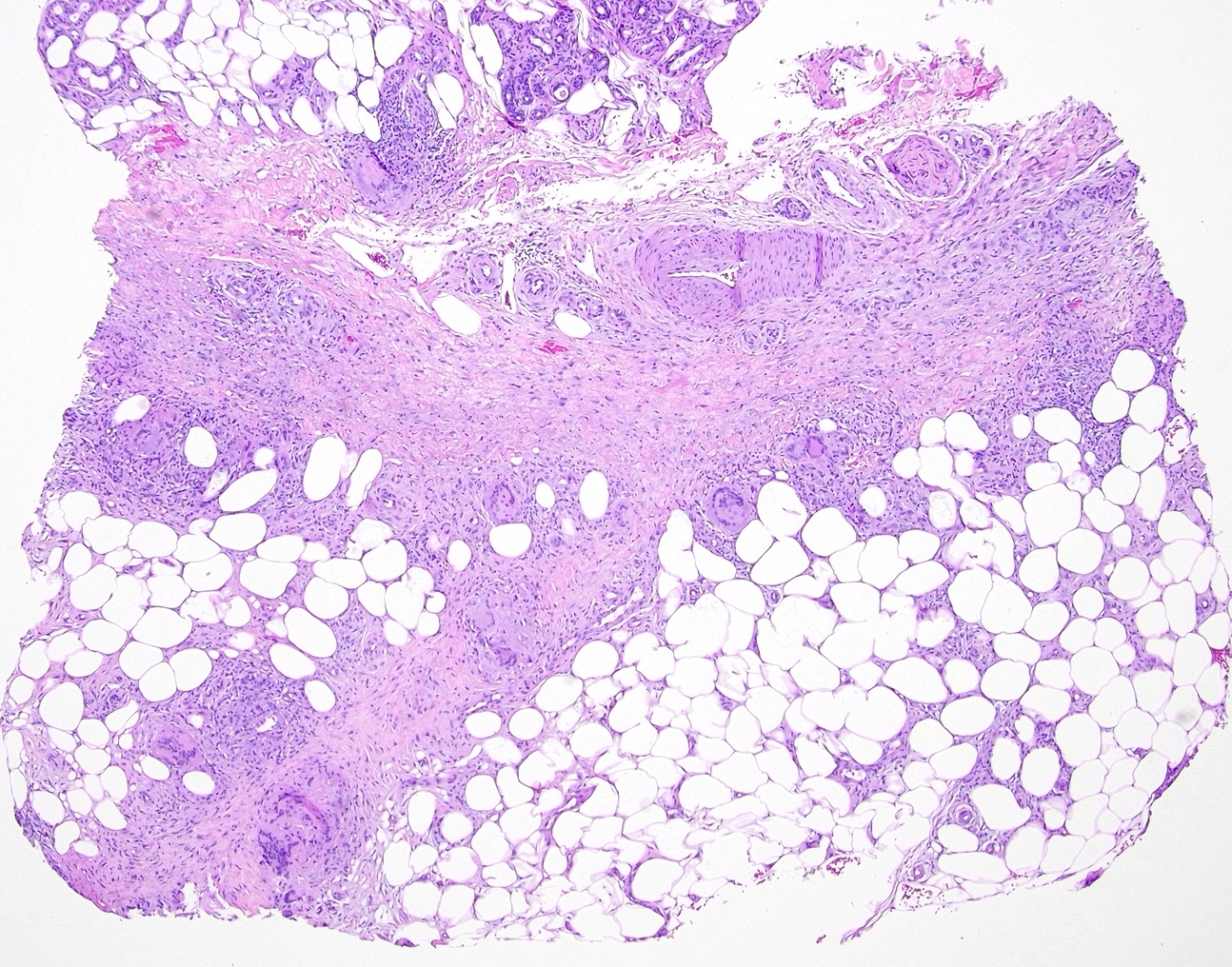

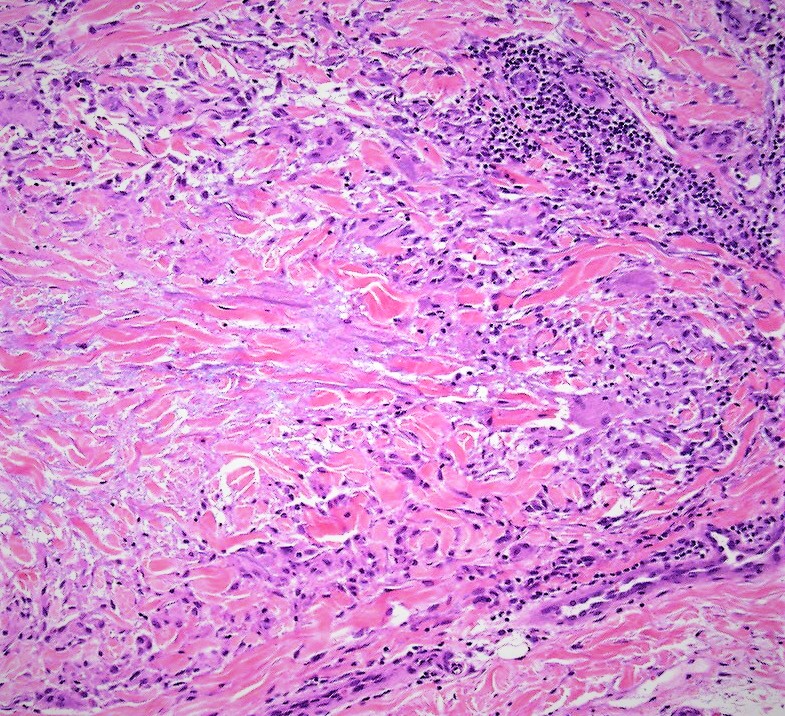

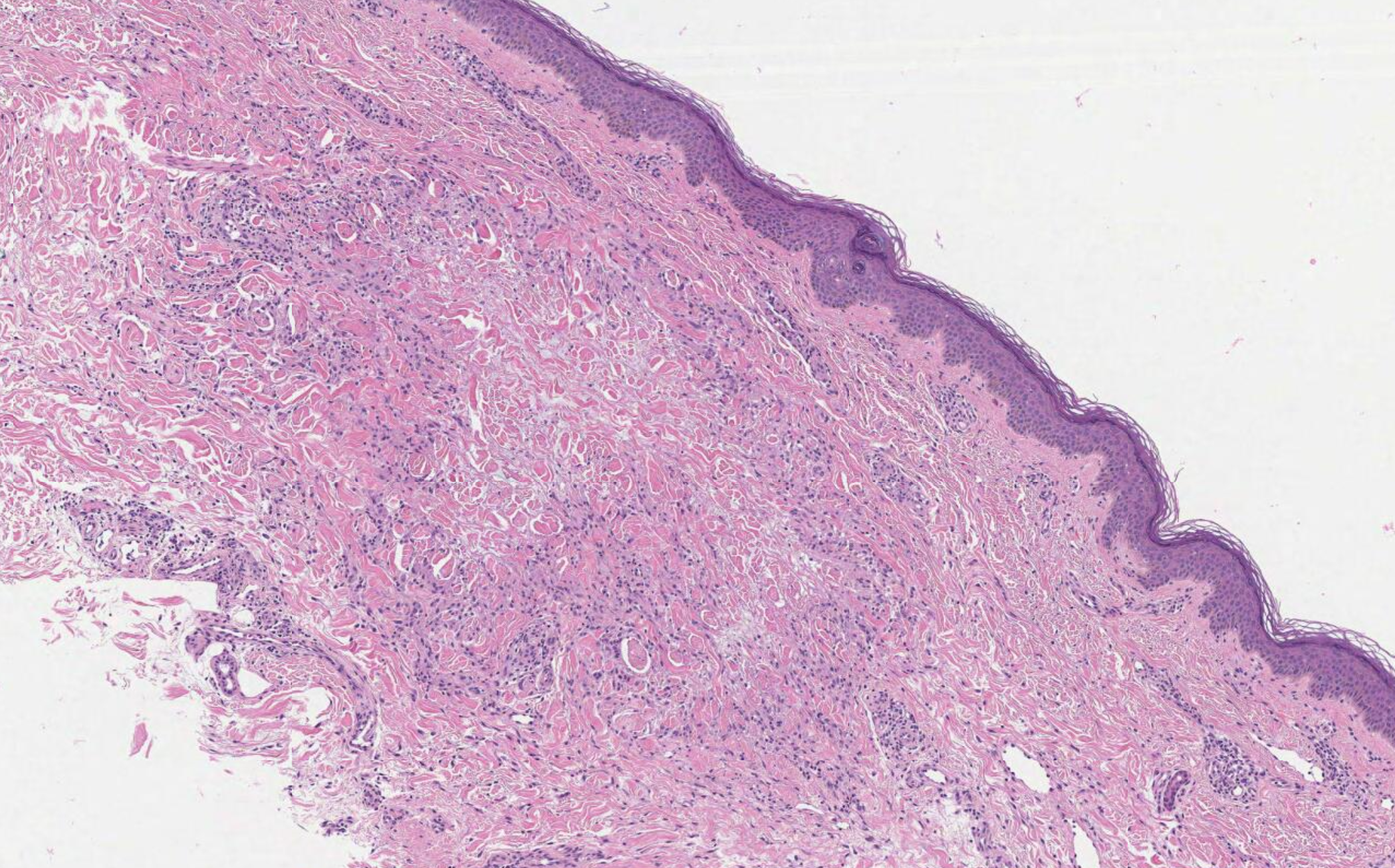

Lipodermatosclerosis: Sclerosing panniculitis, also known as lipodermatosclerosis, results from chronic venous insufficiency of the lower extremities. Histopathological findings vary by stage. Early stages present with ischemic necrosis of the lobule center, sparse lymphocytic infiltrate, and extravasation of erythrocytes and hemosiderin (see Image. Sclerosing Panniculitis, Low Power). Late-stage lesions show sclerosis of the septa, fat necrosis, and lipomembranous change, which is observed as an eosinophilic feathery lining composed of anuclear cystic adipocytes.[55] Lipomembranous change suggests lipodermatosclerosis (see Image. Sclerosing Panniculitis, High Power).

Factitial or traumatic panniculitis: Factitial or traumatic panniculitides, such as encapsulated fat necrosis, should be considered when histopathology shows unusual features without vasculitis or thrombosis. These conditions may result from self-inflicted injuries or iatrogenic causes, including cosmetic or therapeutic substances. They may arise from accidental or intentional blunt trauma.

Histopathology typically shows mostly lobular panniculitis with a predominantly neutrophilic inflammatory infiltrate in acute stages and a more granulomatous infiltrate in late stages. For example, cosmetic silicone injections may result in a granulomatous reaction in some patients, showing foamy histiocytes and multinucleated giant cells. Vitamin K injections may present on histopathology with sclerosis of collagen bundles in the septa and lymphocytic and plasma cell inflammatory infiltrates that may resemble deep morphea.[56]

Alternately, areas of fat necrosis in the subcutis with cystic spaces of variable size and shape within fat lobules and varying degrees of hemorrhage and fibrosis may be observed (see Image. Traumatic Panniculitis Pathology). The periphery of the lesions may have necrotic adipocytes without nuclei.[57]

Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis: This condition can occur following irradiation. Histopathology may show thickened, sclerotic septa and lobular panniculitis.[58][59]

Neutrophilic panniculitis: The erythematous, tender lesions of neutrophilic panniculitis may be associated with neutrophilic dermatoses, such as Behcet syndrome. Histopathology reveals heavy neutrophilic infiltrates within the fat lobules.[60][61]

Eosinophilic panniculitis: Eosinophilic panniculitis shows septal and lobular panniculitis with eosinophils and flame figures. Although not a specific diagnosis, this condition is a reaction pattern associated with infection, such as gnathostomiasis.[62][63]

Predominantly Lobular Panniculitides With Vasculitis

Predominantly lobular panniculitides with vasculitis may affect arteries and veins. This set of conditions includes the following:

Erythema induratum of Bazin: Erythema induratum of Bazin, also known as nodular vasculitis, is the most common type of lobular panniculitis with vasculitis and may affect both veins and arteries (see Image. Erythema Induratum of Bazin). Tuberculosis has been implicated as one of the possible causes of this syndrome. Histopathology in the early stages typically shows neutrophils with extensive necrosis of adipocytes, foamy histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells. Caseous necrosis and liquefaction may appear when arteries are severely damaged.

Neutrophilic lobular panniculitis: Neutrophilic lobular panniculitis is an unusual and rare variant of panniculitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. The condition presents histopathologically with lobule adipocyte necrosis, neutrophils, foamy histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells.[64]

Lucio phenomenon: Lucio phenomenon is a variant of leprosy that presents with necrotizing vasculitis of the dermis and subcutis, mainly affecting the smaller vessels and venules. The predominant cell type relating to perivascular inflammation includes foamy histiocytes that contain acid-fast bacilli.[65]

Erythema nodosum leprosum: Erythema nodosum leprosum presents as a necrotizing vasculitis involving small-to-medium–sized vessels of the dermis and subcutis. The predominant cell type is the neutrophil.

Weber-Christian disease is sometimes considered a type of panniculitis characterized by numerous lipophages, but it is probably best described as idiopathic panniculitis. Some cases of Weber-Christian disease have later been discovered to fit with other entities. Thus, this term, along with Rothmann-Makai syndrome, is no longer used.[66][67]

Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma is a rare cutaneous lymphoma that should be distinguished from panniculitis.[68] Histopathology typically shows a lobular panniculitis pattern but with pleomorphic, neoplastic lymphocytes and histiocytes rimming adipocytes to form a lace- or net-like pattern.[69][70]

Other causes of lobular panniculitis include atheromatous emboli, Behcet disease, blind loop syndrome, chemotherapy recall reaction, Crohn disease, dermatomyositis, granuloma annulare, hydroa vacciniforme, jejunoileal bypass, lymphoma, Niemann-Pick disease, nutritional abnormalities, oxalosis, Sjogren syndrome, Sweet syndrome, gout, medications, and infections.[71]

Clinical Significance

Panniculitis is a relatively uncommon disorder characterized by various histopathological features and encompasses a range of subtypes linked to infection, trauma, malignancy, or inflammatory diseases.

Patients typically present with tender, erythematous, subcutaneous nodules or plaques, most often on the lower extremities. However, certain types of panniculitides develop preferentially in certain areas, such as the calf for erythema induratum, the pretibial region for erythema nodosum, and the upper arms, shoulders, and face for lupus panniculitis.[72] Depending on the etiology, panniculitis may also present with ulcers, atrophy, sclerosis, or livedo racemosa.[73] Additional systemic features may include fever, weight loss, malaise, and arthralgia.[74]

Panniculitis is diagnosed and classified using a combined approach, including clinical presentation and histopathological correlation based on biopsy findings. Diagnosis sometimes requires additional tests and studies, including microbiological cultures, lab tests, and polarized light microscopy.

Management focuses on panniculitis resolution and treatment of the underlying illness. The recommended measures include:

- Rest and elevation of affected areas

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- Supportive care

- Compression stockings

- Antibiotics

- Systemic steroids

- Immunosuppressants

- Biologics

- Surgical removal of nonhealing lesions

Panniculitis may last weeks to months, and the outcome depends on the underlying cause of inflammation. Lesions may resolve spontaneously and recur. Some forms of panniculitis heal without sequelae, but others may cause significant morbidity, resulting in scarring or disfigurement.

Panniculitis is a relatively uncommon disorder encountered in clinical practice. However, the condition is best managed by an interdisciplinary team that may include a variety of practitioners, as the specific etiologies and histopathological subtypes differ significantly. Dermatology, rheumatology, pediatrics, and primary care may coordinate with pathology in managing the various panniculitis subtypes. Systemic disease-associated types may also involve oncology, infectious disease, gastroenterology, nephrology, or pulmonology.

When initially presenting for evaluation, a trained clinician should perform the deep punch or incisional scalp biopsy to obtain a sufficient sample for the pathologist's evaluation. A shave biopsy is too superficial and should not be used for lesions suspected of panniculitis.

Coordination between primary care providers and specialists in dermatology and dermatopathology is crucial for optimal patient care. Identifying the etiology of panniculitis can be challenging, especially if the practitioner is not well-versed in the diverse range of potential underlying conditions or the appropriate biopsy techniques. Once a diagnosis is made through clinical and histopathologic correlation, managing panniculitis effectively involves addressing the underlying cause. Given that different organ systems may be affected depending on the etiology, an interprofessional team approach is essential to improving outcomes.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma Pathology, Low Power. Histopathology shows large areas of necrobiosis alternating with granulomatous inflammation, including foamy histiocytes, cholesterol clefts, and Touton giant cells, which are characterized by a wreath of nuclei surrounded by a peripheral rim of foamy cytoplasm.

Contributed by P Chu, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Necrobiotic Xanthogranuloma Pathology, High Power. Histopathology shows large areas of necrobiosis alternating with granulomatous inflammation, including foamy histiocytes, cholesterol clefts, and Touton giant cells, which are characterized by a wreath of nuclei surrounded by a peripheral rim of foamy cytoplasm.

Contributed by P Chu, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis of the Newborn, Low Power. This image shows subcutaneous fat necrosis, a self-resolving panniculitis in neonates, typically affecting the thighs, cheeks, and buttocks. Key histopathological features include needle-shaped clefts within adipocytes, indicative of the condition's hallmark.

Contributed by P Chu, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Safi R, El Hasbani G, Bardawil T, Abbas O, Kibbi AG, Nassar D. Investigating the presence of neutrophil extracellular traps in septal and lobular cutaneous panniculitides. International journal of dermatology. 2021 Jun:60(6):724-729. doi: 10.1111/ijd.15450. Epub 2021 Feb 13 [PubMed PMID: 33580883]

Anand NC, Takaichi M, Johnson EF, Wetter DA, Davis MDP, Alavi A. Suggestions for a New Clinical Classification Approach to Panniculitis Based on a Mayo Clinic Experience of 207 Cases. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2022 Sep:23(5):739-746. doi: 10.1007/s40257-022-00709-9. Epub 2022 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 35849324]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWick MR. Panniculitis: A summary. Seminars in diagnostic pathology. 2017 May:34(3):261-272. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2016.12.004. Epub 2016 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 28129926]

Zheng W, Song W, Wu Q, Yin Q, Pan C, Pan H. Analysis of the clinical characteristics of thirteen patients with Weber-Christian panniculitis. Clinical rheumatology. 2019 Dec:38(12):3635-3641. doi: 10.1007/s10067-019-04722-y. Epub 2019 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 31402393]

Requena L, Yus ES. Panniculitis. Part I. Mostly septal panniculitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2001 Aug:45(2):163-83; quiz 184-6 [PubMed PMID: 11464178]

Elston DM, Stratman EJ, Miller SJ. Skin biopsy: Biopsy issues in specific diseases. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2016 Jan:74(1):1-16; quiz 17-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.033. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26702794]

Diaz Cascajo C, Borghi S, Weyers W. Panniculitis: definition of terms and diagnostic strategy. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 2000 Dec:22(6):530-49 [PubMed PMID: 11190446]

Zelger B. Panniculitides, an algorithmic approach. Giornale italiano di dermatologia e venereologia : organo ufficiale, Societa italiana di dermatologia e sifilografia. 2013 Aug:148(4):351-70 [PubMed PMID: 23900158]

Blackshear CP, Borrelli MR, Shen EZ, Ransom RC, Chung NN, Vistnes SM, Irizarry D, Nazerali R, Momeni A, Longaker MT, Wan DC. Utilizing Confocal Microscopy to Characterize Human and Mouse Adipose Tissue. Tissue engineering. Part C, Methods. 2018 Oct:24(10):566-577. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2018.0154. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30215305]

Sánchez Yus E, Sanz Vico MD, de Diego V. Miescher's radial granuloma. A characteristic marker of erythema nodosum. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 1989 Oct:11(5):434-42 [PubMed PMID: 2679196]

Pérez-Garza DM, Chavez-Alvarez S, Ocampo-Candiani J, Gomez-Flores M. Erythema Nodosum: A Practical Approach and Diagnostic Algorithm. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2021 May:22(3):367-378. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00592-w. Epub 2021 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 33683567]

Sayama K, Chen M, Shiraishi S, Miki Y. Morphea profunda. International journal of dermatology. 1991 Dec:30(12):873-5 [PubMed PMID: 1816132]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRequena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. Part II. Mostly lobular panniculitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2001 Sep:45(3):325-61; quiz 362-4 [PubMed PMID: 11511831]

Requena L, Fernández-Figueras MT. Subcutaneous granuloma annulare. Seminars in cutaneous medicine and surgery. 2007 Jun:26(2):96-9 [PubMed PMID: 17544961]

Joshi TP, Duvic M. Granuloma Annulare: An Updated Review of Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Treatment Options. American journal of clinical dermatology. 2022 Jan:23(1):37-50. doi: 10.1007/s40257-021-00636-1. Epub 2021 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 34495491]

Johnson E, Patel MH, Brumfiel CM, Severson KJ, Bhullar P, Boudreaux B, Butterfield RJ, DiCaudo DJ, Nelson SA, Pittelkow MR, Mangold AR. Histopathologic features of necrobiosis lipoidica. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2022 Aug:49(8):692-700. doi: 10.1111/cup.14238. Epub 2022 Apr 25 [PubMed PMID: 35403265]

Chopra R, Chhabra S, Thami GP, Punia RP. Panniculitis: clinical overlap and the significance of biopsy findings. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2010 Jan:37(1):49-58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2009.01404.x. Epub 2009 Aug 25 [PubMed PMID: 19708879]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHolt A, Servattalab S, Yim K, Kirkorian AY, O'Donnell P, Wiss K. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn with fluctuant nodules mimicking infection. JAAD case reports. 2024 Jun:48():30-32. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2024.03.019. Epub 2024 Apr 9 [PubMed PMID: 38766391]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRegaieg C, Thabet AB, Kolsi N, Sellami K, Turki H, Charfi M, Hmida N. Congenital liquified subcutaneous fat necrosis in a newborn: an unusual case. Dermatology online journal. 2024 Mar 15:30(1):. doi: 10.5070/D330163295. Epub 2024 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 38762865]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSilverman RA, Newman AJ, LeVine MJ, Kaplan B. Poststeroid panniculitis: a case report. Pediatric dermatology. 1988 May:5(2):92-3 [PubMed PMID: 3412997]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGuillen-Climent S, García Vázquez A, Estébanez A, Pons Benavent M, Folch Briz R, Gil Viana R, Sáez-Martín LC, María Martín J, Ramón Quiles MD. Subcutaneous fat necrosis of the newborn: clinical and histopathological review and use of cutaneous ultrasound Necrosis grasa subcutánea del recién nacido: revisión clínica e histopatológica y utilidad de la ecografía cutánea. Dermatology online journal. 2020 Nov 15:26(11):. pii: 13030/qt82j1s7k4. Epub 2020 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 33342185]

Alhalabi R, Salloum R, Alhalabi D, Oun Y, Abudeeb J, Kikhia J, Mouhamad M. Sclerema neonatorum in a premature newborn: A case report. Skin health and disease. 2023 Oct:3(5):e255. doi: 10.1002/ski2.255. Epub 2023 May 25 [PubMed PMID: 37799354]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceNakalema G, Egesa WI, Kumbakulu PK, Nduwimana M, Anaya AD, Kizito MS, Kavuma D. Sclerema Neonatorum in a Term Infant: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case reports in pediatrics. 2020:2020():8837064. doi: 10.1155/2020/8837064. Epub 2020 Dec 30 [PubMed PMID: 33489400]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceStoran ER, O' Gorman SM, Hawkins P, Aalto L, Murphy A, Markham T. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency-related panniculitis: two cases with diverse clinical courses. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2017 Jul:42(5):520-522. doi: 10.1111/ced.13102. Epub 2017 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 28512995]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMcElvaney OF, Fraughen DD, McElvaney OJ, Carroll TP, McElvaney NG. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: current therapy and emerging targets. Expert review of respiratory medicine. 2023 Mar:17(3):191-202. doi: 10.1080/17476348.2023.2174973. Epub 2023 Mar 15 [PubMed PMID: 36896570]

Geller JD, Su WP. A subtle clue to the histopathologic diagnosis of early alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency panniculitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1994 Aug:31(2 Pt 1):241-5 [PubMed PMID: 8040408]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFranciosi AN, Ralph J, O'Farrell NJ, Buckley C, Gulmann C, O'Kane M, Carroll TP, McElvaney NG. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency-associated panniculitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2022 Oct:87(4):825-832. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.01.074. Epub 2021 Jan 29 [PubMed PMID: 33516773]

Yang J, Chen L, Shi R, Zhao X, Pan M, Zheng J. Cytophagic Histiocytic Panniculitis Presenting as Subcutaneous Nodules and Generalized Edema - A Case Report. Clinical, cosmetic and investigational dermatology. 2023:16():3541-3545. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S437208. Epub 2023 Dec 12 [PubMed PMID: 38107669]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMoshayedi A, Shea S, Nandan A, Ford S. Cytophagic Histiocytic Panniculitis and Kikuchi-Fujimoto-Like Lymphadenitis in a Patient With Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Cureus. 2022 Sep:14(9):e28951. doi: 10.7759/cureus.28951. Epub 2022 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 36237739]

Perfetto J, Behrens EM, Lerman MA, Paessler ME, Liebling EJ. Avoid a rash diagnosis: reconsidering cytophagic histiocytic panniculitis as a distinct clinical-pathologic entity. JAAD case reports. 2023 Jun:36():40-44. doi: 10.1016/j.jdcr.2023.03.019. Epub 2023 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 37215298]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCortes M, Smirnov BP. Painful subcutaneous nodules in an alcoholic: a case of pancreatic panniculitis. Dermatology online journal. 2023 Dec 15:29(6):. doi: 10.5070/D329663005. Epub 2023 Dec 15 [PubMed PMID: 38478676]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBall NJ, Adams SP, Marx LH, Enta T. Possible origin of pancreatic fat necrosis as a septal panniculitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1996 Feb:34(2 Pt 2):362-4 [PubMed PMID: 8655727]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFijałkowska A, Kądziela M, Żebrowska A. The Spectrum of Cutaneous Manifestations in Lupus Erythematosus: A Comprehensive Review. Journal of clinical medicine. 2024 Apr 21:13(8):. doi: 10.3390/jcm13082419. Epub 2024 Apr 21 [PubMed PMID: 38673692]

Vale ECSD, Garcia LC. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus: a review of etiopathogenic, clinical, diagnostic and therapeutic aspects. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2023 May-Jun:98(3):355-372. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2022.09.005. Epub 2023 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 36868923]

Sánchez NP, Peters MS, Winkelmann RK. The histopathology of lupus erythematosus panniculitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1981 Dec:5(6):673-80 [PubMed PMID: 7033308]

Winkelmann RK, Padilha-Goncalves A. Connective tissue panniculitis. Archives of dermatology. 1980 Mar:116(3):291-4 [PubMed PMID: 7369744]

Gargiulo L, Chiara Tronconi M, Grimaudo MS, Pavia G, Valenti M, Manara S, Costanzo A, Borroni RG. Connective tissue panniculitis and vitiligo in a patient with stage IV melanoma achieving complete response to dabrafenib and trametinib combination therapy. Melanoma research. 2021 Dec 1:31(6):586-588. doi: 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000787. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34620756]

Cedirian S, Comellini V, Chessa MA, Ravaioli GM, Misciali C, Nava S, LA Placa M. Subcutaneous sarcoidosis: a case series from a single center. Italian journal of dermatology and venereology. 2024 Jun:159(3):344-348. doi: 10.23736/S2784-8671.24.07711-9. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38808460]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNogueira VB, de Oliveira Mendes-Aguiar C, Teixeira DG, Freire-Neto FP, Tassi LZ, Ferreira LC, Wilson ME, Lima JG, Jeronimo SMB. Impaired signaling pathways on Berardinelli-Seip congenital lipodystrophy macrophages during Leishmania infantum infection. Scientific reports. 2024 May 16:14(1):11236. doi: 10.1038/s41598-024-61663-6. Epub 2024 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 38755198]

Liu Q, Pan M, Cao H, Zheng J, Ruan YP, Zhao XQ. Acquired generalized lipodystrophy in a juvenile dermatomyositis patient. International journal of rheumatic diseases. 2024 Mar:27(3):e15101. doi: 10.1111/1756-185X.15101. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38445875]

Freire EBL, Brasil d'Alva C, Madeira MP, Lima GEDCP, Fernandes VO, Aguiar LB, Portella LB, Galvão Ozório R, Ponte CMM, Montenegro APDR, Montenegro Junior RM. Heterogeneity and high prevalence of bone manifestations, and bone mineral density in congenital generalized lipodystrophy subtypes 1 and 2. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2024:15():1326700. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1326700. Epub 2024 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 38633760]

Magno S, Ceccarini G, Corvillo F, Pelosini C, Gilio D, Paoli M, Fornaciari S, Pandolfo G, Sanchez-Iglesias S, Nozal P, Curcio M, Sessa MR, López-Trascasa M, Araújo-Vilar D, Santini F. Clinical Characteristics of Patients With Acquired Partial Lipodystrophy: A Multicenter Retrospective Study. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 2024 Feb 20:109(3):e932-e944. doi: 10.1210/clinem/dgad700. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38061004]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAcharya S, Kandel S, Shrestha S, Tiwari SB, Sapkota S, Bhattarai A, Jha S. Barraquer-Simons syndrome in systemic lupus erythematosus: A case report. Clinical case reports. 2021 Nov:9(11):e05132. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.5132. Epub 2021 Nov 22 [PubMed PMID: 34849231]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceValerio CM, Muniz RBG, Viola LF, Bartzen Pereira G, Moreira RO, de Sousa Berriel MR, Montenegro Júnior RM, Godoy-Matos AF, Zajdenverg L. Gestational and neonatal outcomes of women with partial Dunnigan lipodystrophy. Frontiers in endocrinology. 2024:15():1359025. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2024.1359025. Epub 2024 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 38633761]

Sandler M, Shah N, Fedeles F, Tiao J. A Retrospective Study of Adult Patients with Parry Romberg Syndrome. Clinical and experimental dermatology. 2024 May 3:():. pii: llae165. doi: 10.1093/ced/llae165. Epub 2024 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 38699951]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMorguetti MJ, Neves PDMM, Korkes I, Padilha WSC, Jorge LB, Watanabe A, Watanabe EH, Malheiros DMAC, Noronha IL, Dib SA, Onuchic LF, Moisés RS. Podocytopathies associated with familial partial lipodystrophy due to LMNA variants: report of two cases. Archives of endocrinology and metabolism. 2024 May 10:68():e230204. doi: 10.20945/2359-4292-2023-0204. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38739524]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCook IF. Localized lipoatrophy and inadvertent subcutaneous administration of a COVID-19 vaccine. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics. 2022 Nov 30:18(5):2042136. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2022.2042136. Epub 2022 Mar 8 [PubMed PMID: 35258436]

Hashem R, Mulnier H, Abu Ghazaleh H, Halson-Brown S, Duaso M, Rogers R, Karalliedde J, Forbes A. Characteristics and morphology of lipohypertrophic lesions in adults with type 1 diabetes with ultrasound screening: an exploratory observational study. BMJ open diabetes research & care. 2021 Dec:9(2):. doi: 10.1136/bmjdrc-2021-002553. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34876413]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceDemir G, Er E, Atik Altınok Y, Özen S, Darcan Ş, Gökşen D. Local complications of insulin administration sites and effect on diabetes management. Journal of clinical nursing. 2022 Sep:31(17-18):2530-2538. doi: 10.1111/jocn.16071. Epub 2021 Oct 8 [PubMed PMID: 34622517]

von Atzigen J, Burger A, Grünherz L, Barbon C, Felmerer G, Giovanoli P, Lindenblatt N, Wolf S, Gousopoulos E. A Comparative Analysis to Dissect the Histological and Molecular Differences among Lipedema, Lipohypertrophy and Secondary Lymphedema. International journal of molecular sciences. 2023 Apr 20:24(8):. doi: 10.3390/ijms24087591. Epub 2023 Apr 20 [PubMed PMID: 37108757]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJussila A, Zhang B, Kirti S, Atit R. Tissue fibrosis associated depletion of lipid-filled cells. Experimental dermatology. 2024 Mar:33(3):e15054. doi: 10.1111/exd.15054. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38519432]

Zhao X, Liu Y, Xiang X, Wang Z, Chen Y, Miao C, Xu Z. Clinicopathological characteristics, treatment and follow-up of lipodystrophia centrifugalis abdominalis infantilis: A retrospective case series in China. The Australasian journal of dermatology. 2024 Mar:65(2):182-184. doi: 10.1111/ajd.14203. Epub 2023 Dec 14 [PubMed PMID: 38095123]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLamesa TA. Biological Depiction of Lipodystrophy and Its Associated Challenges Among HIV AIDS Patients: Literature Review. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, N.Z.). 2024:16():123-132. doi: 10.2147/HIV.S445605. Epub 2024 Apr 3 [PubMed PMID: 38584795]

Soares JLM, Rocha VA, Sanudo A, Miot HA, Bagatin E. Prevalence and factors associated with gynoid lipodystrophy in Brazilian adolescent girls: a cross-sectional study. International journal of dermatology. 2022 Jul:61(7):861-866. doi: 10.1111/ijd.16061. Epub 2022 Jan 26 [PubMed PMID: 35080006]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceAlegre VA, Winkelmann RK, Aliaga A. Lipomembranous changes in chronic panniculitis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1988 Jul:19(1 Pt 1):39-46 [PubMed PMID: 3042817]

Janin-Mercier A, Mosser C, Souteyrand P, Bourges M. Subcutaneous sclerosis with fasciitis and eosinophilia after phytonadione injections. Archives of dermatology. 1985 Nov:121(11):1421-3 [PubMed PMID: 2932062]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKiryu H, Rikihisa W, Furue M. Encapsulated fat necrosis--a clinicopathological study of 8 cases and a literature review. Journal of cutaneous pathology. 2000 Jan:27(1):19-23 [PubMed PMID: 10660127]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHashim PW, Vyas NS, Abyaneh MY, Goldberg MS. Postirradiation Pseudosclerodermatous Panniculitis: A Rare Complication of Megavoltage External Beam Radiotherapy. Cutis. 2022 May:109(5):E35-E37. doi: 10.12788/cutis.0539. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35856749]

Garrido PM, Fernandes I, Pina MF, Soares-Almeida L, Filipe P, Borges-Costa J. Postirradiation pseudosclerodermatous panniculitis mimicking a Kaposi sarcoma recurrence. International journal of dermatology. 2019 Dec:58(12):e249-e250. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14593. Epub 2019 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 31334836]

Maniam GB, Coakley A, Huong Nguyen G, Alavi A, Davis MDP. Neutrophilic Panniculitides. Dermatologic clinics. 2024 Apr:42(2):285-295. doi: 10.1016/j.det.2023.08.005. Epub 2023 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 38423687]

Almeida Junior HL, Furtado VD, Issaacson VS, Boff AL. Successful treatment of rheumatoid neutrophilic panniculitis with tofacitinib. Anais brasileiros de dermatologia. 2024 Jul-Aug:99(4):644-647. doi: 10.1016/j.abd.2023.05.010. Epub 2024 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 38658238]

Graeff-Teixeira C, Pauli DS, Zicarelli CAM, Pascoal VF, Paiva-Novaes EP, Chagas JPS, Kersanach BB, Hadad DJ, Walger-Schultz LK. Gnathostoma infection after ingestion of raw fish is a probable cause of eosinophilic meningitis in the Brazilian Amazon. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical. 2024:57():e008012024. doi: 10.1590/0037-8682-0434-2023. Epub 2024 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 38451691]

Sandhu J, Gupta SK, Garg B. Erythematous, Non-Tender Plaques on the Shins: A Case of Idiopathic Eosinophilic Panniculitis. Indian journal of dermatology. 2022 Jul-Aug:67(4):480. doi: 10.4103/ijd.ijd_1040_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 36578744]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTran TA, DuPree M, Carlson JA. Neutrophilic lobular (pustular) panniculitis associated with rheumatoid arthritis: a case report and review of the literature. The American Journal of dermatopathology. 1999 Jun:21(3):247-52 [PubMed PMID: 10380046]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePursley TV, Jacobson RR. Lucio's phenomenon. Archives of dermatology. 1980 Feb:116(2):201-4 [PubMed PMID: 7356353]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceWhite JW Jr, Winkelmann RK. Weber-Christian panniculitis: a review of 30 cases with this diagnosis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 1998 Jul:39(1):56-62 [PubMed PMID: 9674398]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceZelickson BD, Winkelmann RK. Lipophagic panniculitis in re-excision specimens. Acta dermato-venereologica. 1991:71(1):59-61 [PubMed PMID: 1676218]

Tran NT, Nguyen KT, Le LT, Nguyen KT, Trinh CT, Hoang VT. Subcutaneous Panniculitis-Like T-Cell Lymphoma With Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis. Journal of investigative medicine high impact case reports. 2024 Jan-Dec:12():23247096241253337. doi: 10.1177/23247096241253337. Epub [PubMed PMID: 38742532]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAlberti-Violetti S, Avallone G, Colonna C, Tavoletti G, Venegoni L, Merlo V, Cambiaghi S, Marzano AV, Berti E, Cavalli R. Paediatric cutaneous lymphomas including rare subtypes: A 40-year experience at a tertiary referral centre. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology : JEADV. 2024 Apr 23:():. doi: 10.1111/jdv.20028. Epub 2024 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 38650545]

Marchi E, Craig JW, Kalac M. Current and upcoming treatment approaches to uncommon subtypes of PTCL (EATL/MEITL, SPTCL, HSTCL). Blood. 2024 Apr 24:():. pii: blood.2023021788. doi: 10.1182/blood.2023021788. Epub 2024 Apr 24 [PubMed PMID: 38657272]

Ambooken B, Balakrishnan PP, Asokan N, Krishnan J. Ulcerated lobular panniculitis: An unusual initial presentation of anti-Mi-2-alpha positive dermatomyositis. Indian journal of dermatology, venereology and leprology. 2022 May-Jun:88(3):381-384. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_848_2021. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35434985]

Ribeiro R, Patrício C, Pais da Silva F, Silva PE. Erythema induratum of Bazin and Ponçet's arthropathy as epiphenomena of hepatic tuberculosis. BMJ case reports. 2016 Mar 4:2016():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-213585. Epub 2016 Mar 4 [PubMed PMID: 26944370]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKunovsky L, Dite P, Brezinova E, Sedlakova L, Trna J, Jabandziev P. Skin manifestations of pancreatic diseases. Biomedical papers of the Medical Faculty of the University Palacky, Olomouc, Czechoslovakia. 2022 Dec:166(4):353-358. doi: 10.5507/bp.2022.035. Epub 2022 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 35938387]

Ng TTW, Davel S, O'Connor KD. Sulfasalazine-Induced Delayed Hypersensitivity Reaction Presenting as Fever, Aseptic Meningitis, and Mesenteric Panniculitis in a Patient with Seronegative Arthritis. The American journal of case reports. 2023 Nov 4:24():e941623. doi: 10.12659/AJCR.941623. Epub 2023 Nov 4 [PubMed PMID: 37924204]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence