Introduction

Transverse myelitis (TM) is a rare, acquired focal inflammatory disorder often presenting with rapid onset weakness, sensory deficits, and bowel/bladder dysfunction. Generally occurring independently, often as a complication of infection, it may also exist as part of a continuum of other neuro-inflammatory disorders.[1] Some of the included continua are acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, and acute flaccid myelitis. TM generally occurs in the spinal cord at any level but most commonly affects the thoracic region. The disorder transverses the spinal cord, causing bilateral deficiencies. However, there may only be partial or asymmetric involvement. The duration of this disease may be as little as 3 to 6 months or may become permanently debilitating. At peak deficit, 50% of patients are completely paraplegic, with virtually all of the patients having a degree of bladder/bowel dysfunction.[2] Approximately 33% of patients recover with little to no lasting deficits, 33% have a moderate degree of permanent disability, and 33% are permanently disabled.[2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

There are multiple causes of TM, but can they be broadly divided into idiopathic, postinfectious, systemic inflammation, or multifocal central nervous system disease.[3] The most common cause of TM is idiopathic, and no causative factor is found. Infections leading to TM include but are not limited to, enteroviruses, West Nile virus, herpes viruses, HIV, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1), Zika virus, neuroborreliosis (Lyme), Mycoplasma, and Treponema pallidum.[4] Some of the acquired central nervous system autoimmune disorders include multiple sclerosis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, and acute disseminated encephalomyelitis. Neurosarcoidosis and paraneoplastic syndromes also have been reported to have an association with TM. Systemic inflammatory autoimmune disorders that have an association with TM include ankylosing spondylitis, antiphospholipid syndrome, Behçet disease, mixed connective tissue disease, rheumatoid arthritis, sarcoidosis, scleroderma, Sjögren syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus.[5][6][7]

Epidemiology

TM can affect men and women equally. Women tend to predominate those associated with multiple sclerosis.[8] TM can affect patients of all ages, but it has spiked occurrences around the ages of 10, 20, and over 40. There is a bimodal peak between ages 10 to 19 and 30 to 39.[9] TM is approximately 1 to 8 new cases per 1 million people annually.[10] There did not appear to be differences in occurrence between Euro/American-born and Afro/Asian-born populations.[10] According to 1 case series, 64% of cases were idiopathic (primary TM), and 36% were associated with a disease (secondary TM). Other reports include idiopathic TM accounting for 15 to 30% of cases.[3]

Histopathology

The histopathophysiology of TM varies and is related to the underlying etiology. Classically, most cases were characterized by perivascular infiltration, demyelination, and axonal injury by monocytes and lymphocytes at the lesion site.[2] Heterogeneity, along with both gray and white matter involvement, gives evidence that this is not a pure demyelinating disorder. TM may be a mixed inflammatory disorder involving neurons, axons, oligodendrocytes, and myelin. Alternative histopathologic causes of TM have been reported to include molecular mimicry and super antigen-mediated disease associated with autoimmune causes.[11]

History and Physical

The onset of TM is acute to subacute. Neurologic symptoms are prominent. Symptoms include motor, sensory, or autonomic dysfunction. Motor deficits include rapidly progressing paraparesis, which can involve the upper extremities initially with flaccidity followed by spasticity. This may be caused by damage to white matter structures in the spinal cord. Most commonly, there is sensory involvement with symptoms, including pain, dysesthesia, and paresthesia at the level involved. Autonomic features of TM include urinary urgency, bladder/bowel incontinence, difficulty/inability to void, bowel constipation, or sexual dysfunction. Urinary retention may be the first sign of myelitis and should warrant further investigation into myelopathy. Motor symptoms may vary depending on the level of the spinal cord involved. Upper cervical lesions (C1-C5) may affect all 4 extremities. Additionally, if the lesion affects the phrenic nerve (C3, C4, C5), it could lead to diaphragmatic dysfunction and respiratory failure. Lesions in the lower cervical levels (C5-T1) may develop upper and lower motor neuron signs in the upper extremities and exclusive upper motor neuron signs in the lower extremities. Cervical lesions account for approximately 20% of cases. Lesions in the thoracic region (T1-T12) may cause upper and lower motor neuron signs in the lower extremities. The thoracic region is the most commonly affected in TM cases (70%). Lesions in the lumbosacral regions (L1-S5) may cause upper and lower motor neuron signs in the lower extremities. Lumbar lesions account for approximately 10% of cases. Sensory symptoms generally affect the level of the lesion or 1 of the levels above or below the lesion. Back pain in the corresponding area of the lesion may also be present.[12]

Evaluation

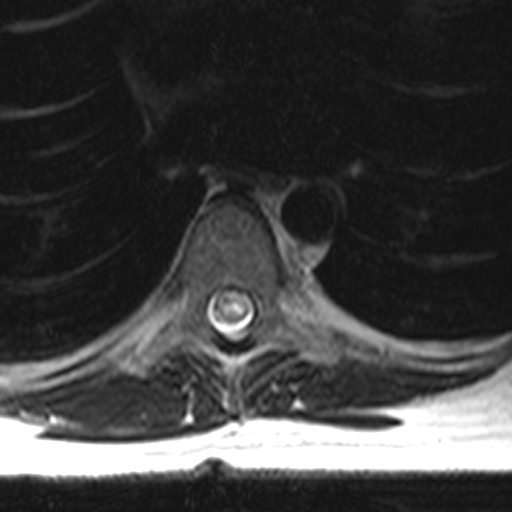

To diagnose TM, a compressive cord lesion must be excluded first. Exclusion is usually performed by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). See Image. Spine MRI, T2 Axial TM. This is followed by a confirmation of inflammation by a gadolinium-enhanced MRI or lumbar puncture (LP). Diagnostic criteria were developed but are generally reserved for research purposes, as not all features must be diagnosed in a clinical setting.[13]

Diagnostic criteria include, with the top 3 being most important:

- Sensory, motor, or autonomic dysfunction originating from the spinal cord

- T2 hyperintense signal changes on MRI

- No evidence of a compressive lesion

- Bilateral signs/symptoms.

- Clearly defined sensory level.

- Gadolinium enhancement on MRI and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis demonstrates evidence of an inflammatory process with pleocytosis or an elevated immunoglobulin G (IgG) index.

- Progression to nadir between 4 hours and 21 days

When considering TM as a possible diagnosis, it is recommended the following investigative analyses be performed:[3]

- MRI of the entire spine with and without gadolinium contrast to differentiate compressive vs. non-compressive lesions.

- Brain MRI with and without gadolinium contrast to evaluate for evidence of brain lesions.

- LP for CSF analysis, including cell count with differential, protein, glucose, the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory test, oligoclonal bands, immunoglobulin G (IgG) index, and cytology.

- Serum anti-aquaporin-4 (APQ-4)-IgG autoantibodies, anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein autoantibodies, B12 level, methylmalonic acid, serum antinuclear antibodies (ANA), Ro/SSA, and La/SSB autoantibodies, syphilis serologies, HIV antibodies, TSH and viral etiology tests as applicable.

Patients with evidence of longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions additionally require the following additional studies, including serum erythrocytes sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, ANA, antibodies to extractable nuclear antigens, rheumatoid factor, antiphospholipid antibodies, and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. They also require computed tomography of the chest to evaluate for evidence of sarcoidosis.[3]

Additional testing may be performed in the appropriate clinical setting.

- Neuro-ophthalmologic evaluation

- Paraneoplastic evaluation

- Infectious serologic and CSF studies

- Nasopharyngeal swab for enteroviral PCR

- Serum copper and ceruloplasmin (copper deficiency may mimic TM)

- Serum vitamin B12 and vitamin E levels

- Spinal angiogram

- Prothrombotic evaluation

- Salivary gland biopsy

Treatment / Management

The standard of care and the first-line therapy for the treatment of TM is intravenous glucocorticoids. High-dose intravenous glucocorticoids should be initiated as soon as possible. There should not be a delay in treatment while waiting for test results. There are few contraindications to glucocorticoid therapy. Potential regimens would include methylprednisolone or dexamethasone for 3 to 5 days. Further duration of therapy should be directed as the clinical case progresses. Plasma exchange may be efficacious for acute central nervous system demyelinating disease, which fails to respond to glucocorticoid therapy.[14][15] Additionally, as knowledge expands regarding TM, immunomodulatory therapy such as cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, or rituximab might benefit chronic recurrent TM or resistant acute TM. Treatment modalities that should also be utilized in the management of TM include pain management, intravenous immunoglobulin, and antivirals.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

A differential diagnosis for TM should include any diseases causing myelopathy. Such examples would include compressive myelopathy from herniated discs, vertebral body compression fractures, epidural abscesses/masses, and spondylitis. Other diagnoses to be included in the differential diagnosis are vascular causes, metabolic/nutritional causes, neoplasms, and radiation. Infectious and autoimmune diseases may be the underlying cause of TM, leading to secondary TM. Treatment would require treating the underlying causes. Guillain-Barré should also be considered when evaluating TM.

Prognosis

Most patients with idiopathic TM should at least have a partial recovery. This recovery should begin within 1 to 3 months and should continue to progress with exercise and rehabilitation therapy.[16] Recovery may take years, and some degree of persistent debilitation may exist. This occurs in approximately 40% of cases.[17] Rapid onset with complete paraplegia and spinal shock is associated with a poorer prognosis. The majority of patients experience TM only once. However, with chronic disease, TM may reoccur. Most recovery occurs within the first 3 months from symptom onset, but recovery can take up to 2 years. If there is no recovery within the first 3 to 6 months, then recovery is unlikely.

Complications

Patients with TM are at risk of developing chronic urinary tract infections, chronic decubitus ulcers, chronic pain, spasticity, major depression, sexual problems, etc. About 5% to 10% of patients who present with TM are at risk of developing multiple sclerosis when presenting with acute complete TM.[18][19] However, this is most likely secondary to multiple sclerosis presenting as TM as its first symptom.

Deterrence and Patient Education

While TM cannot be prevented, patient education helps understand the prognosis, disease course, diagnostic workup, and treatment options. Counseling on the risks and benefits of high-dose steroids is very important. Education of the natural course of the disease that approximately one-third have a full recovery, one-third have a partial recovery, and another third have permanent disabilities is very important. It is also important to educate that the disease is often a monophasic illness and that the disease does not recur unless it is secondary to a chronic comorbid condition. Steroids and immunosuppression are the only potential treatments for acute TM, but there is potential for monoclonal antibody drugs that might alter the disease course. Recovery from the disease requires intensive physical therapy and occupational therapy to maximize good outcomes.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

An interprofessional team that provides a holistic and integrated approach to acute and post-acute care of patients with TM can help achieve the best possible outcomes. Physical therapy and occupational therapy are essential to good outcomes in TM. Early integration of therapies in acute inpatient stay and continuation during rehabilitation can help improve outcomes. In patients who make a meaningful recovery, independence is best achieved with intensive physical and occupational therapy to regain lost function. Coordination of care from in-hospital to out-of-hospital services allows for a smooth transition of care. Consultation with a social worker can help arrange appropriate durable medical equipment at home before discharge. Pharmacists can help with counseling about medication side effects and reviewing drug interactions.

Media

References

West TW, Hess C, Cree BA. Acute transverse myelitis: demyelinating, inflammatory, and infectious myelopathies. Seminars in neurology. 2012 Apr:32(2):97-113. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1322586. Epub 2012 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 22961185]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKrishnan C, Kaplin AI, Pardo CA, Kerr DA, Keswani SC. Demyelinating disorders: update on transverse myelitis. Current neurology and neuroscience reports. 2006 May:6(3):236-43 [PubMed PMID: 16635433]

Beh SC, Greenberg BM, Frohman T, Frohman EM. Transverse myelitis. Neurologic clinics. 2013 Feb:31(1):79-138. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2012.09.008. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23186897]

Neri VC, Xavier MF, Barros PO, Melo Bento C, Marignier R, Papais Alvarenga R. Case Report: Acute Transverse Myelitis after Zika Virus Infection. The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene. 2018 Dec:99(6):1419-1421. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.17-0938. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30277201]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOh DH, Jun JB, Kim HT, Lee SW, Jung SS, Lee IH, Kim SY. Transverse myelitis in a patient with long-standing ankylosing spondylitis. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2001 Mar-Apr:19(2):195-6 [PubMed PMID: 11326484]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Seze J, Lanctin C, Lebrun C, Malikova I, Papeix C, Wiertlewski S, Pelletier J, Gout O, Clerc C, Moreau C, Defer G, Edan G, Dubas F, Vermersch P. Idiopathic acute transverse myelitis: application of the recent diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 2005 Dec 27:65(12):1950-3 [PubMed PMID: 16380618]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMok CC, Lau CS. Transverse myelopathy complicating mixed connective tissue disease. Clinical neurology and neurosurgery. 1995 Aug:97(3):259-60 [PubMed PMID: 7586861]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceScott TF, Frohman EM, De Seze J, Gronseth GS, Weinshenker BG, Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of American Academy of Neurology. Evidence-based guideline: clinical evaluation and treatment of transverse myelitis: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2011 Dec 13:77(24):2128-34. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31823dc535. Epub 2011 Dec 7 [PubMed PMID: 22156988]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceALTROCCHI PH. ACUTE TRANSVERSE MYELOPATHY. Archives of neurology. 1963 Aug:9():111-9 [PubMed PMID: 14048158]

Berman M, Feldman S, Alter M, Zilber N, Kahana E. Acute transverse myelitis: incidence and etiologic considerations. Neurology. 1981 Aug:31(8):966-71 [PubMed PMID: 7196523]

Kaplin AI,Krishnan C,Deshpande DM,Pardo CA,Kerr DA, Diagnosis and management of acute myelopathies. The neurologist. 2005 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 15631640]

West TW. Transverse myelitis--a review of the presentation, diagnosis, and initial management. Discovery medicine. 2013 Oct:16(88):167-77 [PubMed PMID: 24099672]

Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group. Proposed diagnostic criteria and nosology of acute transverse myelitis. Neurology. 2002 Aug 27:59(4):499-505 [PubMed PMID: 12236201]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceWeinshenker BG, O'Brien PC, Petterson TM, Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti CF, Dodick DW, Pineda AA, Stevens LN, Rodriguez M. A randomized trial of plasma exchange in acute central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating disease. Annals of neurology. 1999 Dec:46(6):878-86 [PubMed PMID: 10589540]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceCortese I,Chaudhry V,So YT,Cantor F,Cornblath DR,Rae-Grant A, Evidence-based guideline update: Plasmapheresis in neurologic disorders: report of the Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2011 Jan 18; [PubMed PMID: 21242498]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDefresne P, Hollenberg H, Husson B, Tabarki B, Landrieu P, Huault G, Tardieu M, Sébire G. Acute transverse myelitis in children: clinical course and prognostic factors. Journal of child neurology. 2003 Jun:18(6):401-6 [PubMed PMID: 12886975]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencePidcock FS, Krishnan C, Crawford TO, Salorio CF, Trovato M, Kerr DA. Acute transverse myelitis in childhood: center-based analysis of 47 cases. Neurology. 2007 May 1:68(18):1474-80 [PubMed PMID: 17470749]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBruna J, Martínez-Yélamos S, Martínez-Yélamos A, Rubio F, Arbizu T. Idiopathic acute transverse myelitis: a clinical study and prognostic markers in 45 cases. Multiple sclerosis (Houndmills, Basingstoke, England). 2006 Apr:12(2):169-73 [PubMed PMID: 16629419]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChen L,Li J,Guo Z,Liao S,Jiang L, Prognostic indicators of acute transverse myelitis in 39 children. Pediatric neurology. 2013 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 24112847]