Introduction

A Chance fracture is an unstable spine fracture that typically occurs at the thoracolumbar junction. It is a horizontal fracture extending from posterior to anterior through the spinous process, pedicles, and vertebral body. One can overlook Chance fractures on clinical exam because patients rarely present with a neurological deficit. However, the incidence of concurrent intra-abdominal injuries can be as high as 50%.[1] Early recognition of this injury is critical as a delay in diagnosis significantly impacts clinical outcomes.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

A Chance fracture results from a flexion-distraction injury of the spine. Manchester, UK radiologist G.Q. Chance first described this fracture in 1948 as a “horizontal splitting fracture of the spine."[2] The association between the use of lap seat belts and the Chance fracture was not recognized until the 1960s. Also called a “seat belt fracture,” this injury usually results from a rapid deceleration in a motor vehicle collision. Upon deceleration, the spine forcibly flexes over the lap seat belt, resulting in the distraction of the middle and posterior elements of the spine. Other less common mechanisms of injury include falls and assaults.

Epidemiology

In the United States, there are approximately 160,000 thoracolumbar spine fractures annually. The thoracolumbar junction is the second most common location of spinal injuries, following the cervical spine. About 50% of all spinal injuries outside of the cervical spine occur at the thoracolumbar junction.[3]

Chance fractures often occur in children and young adults, with a male predominance. In a review of Chance fractures by Bernstein et al., the mean patient age was 26 years, with ages ranging from 9 to 54 years and male to female ratio of approximately 3 to 1.[3]

Pathophysiology

The typical location for a chance fracture is at the thoracolumbar region (T10-L2) in most adults; in children is may be located in the mid lumbar area.

The Chance fracture is an unstable flexion-distraction spinal injury with no rotation of the fracture fragments or lateral displacement, as explained by the three-column concept described by Francis Denis.[4][5] According to this concept, the spine is divided into the following three columns:

- Anterior column: anterior longitudinal ligament, anterior annulus, anterior two-thirds of the vertebral body

- Middle column: the posterior third of the vertebral body, posterior annulus, and posterior longitudinal ligament

- Posterior column: posterior elements and posterior ligamentous complex

An injury that involves at least two of the three columns is considered unstable. A Chance fracture involves at least two columns–a distraction-type injury of the middle and posterior columns–with or without an additional compression-type injury of the anterior column.

Chance fractures can be further subdivided into osseous injuries, ligamentous injuries, and osteoligamentous injuries. An osseous Chance injury includes fractures of the spinous process, pedicles, and the vertebral body. A ligamentous Chance injury can involve rupture of the interspinous ligament, posterior longitudinal ligament, ligamentum flavum, facet joint capsule, and intervertebral disc. An osteoligamentous injury includes elements of both osseous and ligamentous injuries.

Chance fractures are unlike other spinal injuries because of their high association of intra-abdominal injuries. The incidence of intra-abdominal injury can be as high as 50%. The most commonly associated intra-abdominal injuries are bowel perforations and mesenteric lacerations,[3] both of which portend a high rate of patient mortality.

History and Physical

The most common mechanism of injury of a Chance fracture is a rapid deceleration in a motor vehicle collision. In this scenario, the patient’s spine forcibly flexes over the lap seatbelt, which serves as a fulcrum. Patients typically present with back pain without neurological deficits. Neurological deficits, such as weakness, numbness, and incontinence, can occur if there is a contusion of the spinal cord or cauda equina due to retropulsion of fracture fragments of the posterior vertebral body cortex.

A significant physical exam finding to assess for is the “seatbelt sign,” which refers to bruising or abrasion on the abdomen in the distribution of a seat belt. This finding is associated with Chance fractures and intra-abdominal injuries. The “seat belt sign” can also be detected on computed tomography as stranding in the subcutaneous fat of the anterior abdominal wall.

Because of the potential for bowel and bladder rupture, it is highly recommended that a surgeon examine all trauma patients with abdominal pain. In addition, a thorough neurological exam is necessary. Both the bladder and rectum should be examined.

Evaluation

The American College of Radiology recommends imaging of the thoracolumbar spine if any of the following are present:[6]

- Back pain or midline tenderness

- Local signs of thoracolumbar injury

- Abnormal neurological signs

- Cervical spine fracture

- Glasgow coma score less than 15

- Major distracting injury

- Alcohol or drug intoxication

For patients, 16 years of age or older with suspected thoracic or lumbar spine trauma, the most appropriate initial imaging study in the ACR Appropriateness Criteria is computed tomography (CT), and CT is superior to radiography for detection of fracture in this population. CT is also the imaging study of choice to assess for concurrent intra-abdominal injuries. If a trauma patient undergoes CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis, the included images of the spine are sufficient, and a separate dedicated spine CT is unnecessary. Obtaining coronal and sagittal reformations is critical to identifying a Chance fracture due to the horizontal orientation of the injury.

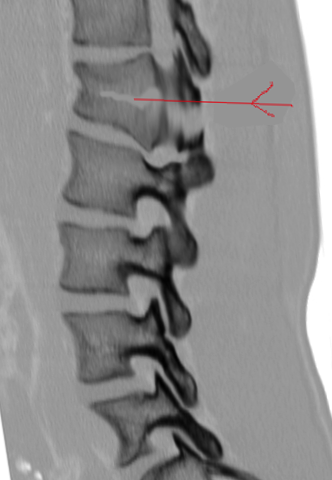

Common CT findings of a Chance fracture include a horizontal fracture through the spinous process, pedicles, and vertebral body, with possible compression of the anterior vertebral body and buckling of the posterior vertebral body. There may also be a distraction of the spinous processes and facet joints at the affected level.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is superior to CT for the detection of soft tissue injuries, including injuries of the ligaments, spinal cord, cauda equina, and intervertebral discs. MRI should be performed in patients with clinical exam findings concerning spinal cord injury/compression or ligamentous injury.

MRI findings of a Chance fracture may include a bright T2 signal (edema) surrounding low signal fracture lines, discontinuity of interspinous ligaments, injury to the intervertebral disc, spinal cord edema, and epidural hematoma.

The American College of Radiology lists radiography of the thoracolumbar spine as the most appropriate initial imaging for children less than 16 years of age with suspected thoracolumbar spine trauma. However, the ACR acknowledges in this document that initial use of CT or MRI of the thoracic and lumbar spine in this setting is controversial, but may be appropriate. In some cases, this distinction may be less important. For instance, if the patient less than 16 years of age undergoes CT imaging for suspected abdominal injuries, the CT imaging of the spine would be available to the interpreting radiologist.

Treatment / Management

Treatment options for Chance fracture include conservative management through immobilization and surgical stabilization. In patients with a purely osseous injury and no neurological deficits, conservative treatment is appropriate. Immobilization in a cast or TLSO (thoracolumbosacral orthosis) can be performed, as bony healing will occur with time. However, neurological deficits and ligamentous injury are indications for surgery. While there are several surgical methods, the literature predominantly supports long-segment posterior fixation using pedicle screws, with or without interbody fusion.[7] Spinal decompression may also be indicated.

The chance fracture is usually reduced on a Risser table by applying hyperextension to the injured thoracolumbar area. A custom-designed plaster or fiberglass is then applied. The biggest drawback is patient compliance because the orthotic device is uncomfortable. The cast is maintained for 8-12 weeks. X-rays are then obtained to determine any residual deformity, but overall, union rates are high with conservative management. An extensive rehabilitation program is necessary to regain muscle strength and mobility.

Conservative management may not be an option in obese and large individuals; these patients may benefit from surgery. The availability of percutaneous techniques of screw insertion has reduced the morbidity of open surgery.

Differential Diagnosis

Burst fracture: Axial loading forces result in vertebral body fracture with a vertical fracture through the posterior elements. In Chance fracture, the fracture of the posterior elements is horizontal in orientation.

Compression fracture: Axial loading forces result in vertebral body fracture without the involvement of the posterior elements. Chance fracture includes a horizontal fracture through the posterior elements.

Distraction injury: Vertical distraction forces result in the distraction of two vertebral bodies, in contrast to horizontal fracture through the spinous process, pedicles, and vertebral body seen in Chance fracture.

Shear injury: Shearing forces result in listhesis of two vertebral bodies, in contrast to horizontal fracture through the spinous process, pedicles, and vertebral body seen in Chance fracture.

Prognosis

Prognosis in a Chance fracture in adults depends on the degree of kyphosis caused by the injury. Those with less than 15 degrees of kyphosis can be treated successfully with an extension cast/orthosis with good to fair results and no neurologic deficit. Chance fractures with more kyphosis are stabilized surgically, with >90% having good results after one year.[8] The degree of kyphosis correlates with the severity of injury in children, also.[9]

Unfortunately, in a significant number of people, low back pain may be a major complaint in the future.

Complications

- Residual low back pain

- Residual deformity leading to kyphosis

- Pressure sores

Postoperative and Rehabilitation Care

After surgery, early mobilization is important. Other factors that need to be addressed include diet, bowel, and bladder function. Prophylaxis against pressure ulcers and deep venous thrombosis must be started.

Deterrence and Patient Education

Careful adherence to current recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics regarding vehicle restraints and adaptations for children may reduce risks of Chance fracture and related injuries in children. [9]

Pearls and Other Issues

A Chance fracture is an unstable, flexion-distraction injury of the spine, typically at the thoracolumbar junction, with a horizontal fracture through the spinous process, pedicles, and vertebral body.

Also known as a “seatbelt fracture,” the most common mechanism of injury is a rapid deceleration in a motor vehicle collision, with flexion of the spine over the lap seat belt.

The incidence of concurrent intra-abdominal injuries is as high as 50%, with bowel perforation and mesenteric laceration being the most common types of injuries. A “seatbelt sign,” or bruising/abrasion on the abdomen in the distribution of a seat belt, should greatly elevate concern for Chance fracture and intra-abdominal injury. This sign can also be identified on computed tomography of the abdomen by inspecting the subcutaneous soft tissues of the anterior abdominal wall.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Diagnosis and management of a chance fracture are best done with an interprofessional team. If the fracture is not appropriately treated, it has enormous morbidity.

Identification of a “seat-belt sign” in the setting of trauma should elevate suspicion for possible Chance fracture, and also for mesenteric and/or intestinal injury. When one of these injuries or signs are identified, the radiologist must search for the other associated injuries to make certain they are not overlooked. Awareness of and communication of the important physical findings that suggest important underlying injuries like Chance fractures and mesenteric and intestinal injuries must be discussed between the caregivers, including emergency physicians, surgeons, and nursing staff, and radiologists who may not see the patient’s physical findings. The general surgeon and urologist must be involved early in the care if there is suspicion of bowel or bladder injuries. Nurses need to provide deep venous thrombosis and pressure ulcer prophylaxis. Most patients have significant pain, and hence the pharmacist should educate the patient on pain medication and assess for drug-drug interactions. Physical therapy is an integral part of treatment and determines outcomes. To improve outcomes, team members must communicate with each other. [Level 5]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Durel R, Rudman E, Milburn J. Clinical images - a quarterly column: chance fracture of the lumbar spine. The Ochsner journal. 2014 Spring:14(1):9-11 [PubMed PMID: 24688326]

CHANCE GQ. Note on a type of flexion fracture of the spine. The British journal of radiology. 1948 Sep:21(249):452 [PubMed PMID: 18878306]

Bernstein MP, Mirvis SE, Shanmuganathan K. Chance-type fractures of the thoracolumbar spine: imaging analysis in 53 patients. AJR. American journal of roentgenology. 2006 Oct:187(4):859-68 [PubMed PMID: 16985126]

AlJallaf M, AlDelail H, Hussein L. Let's review Chance fracture. BMJ case reports. 2015 Feb 19:2015():. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2014-206924. Epub 2015 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 25697298]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDenis F. The three column spine and its significance in the classification of acute thoracolumbar spinal injuries. Spine. 1983 Nov-Dec:8(8):817-31 [PubMed PMID: 6670016]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHsu JM, Joseph T, Ellis AM. Thoracolumbar fracture in blunt trauma patients: guidelines for diagnosis and imaging. Injury. 2003 Jun:34(6):426-33 [PubMed PMID: 12767788]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceLopez AJ, Scheer JK, Smith ZA, Dahdaleh NS. Management of flexion distraction injuries to the thoracolumbar spine. Journal of clinical neuroscience : official journal of the Neurosurgical Society of Australasia. 2015 Dec:22(12):1853-6. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2015.03.062. Epub 2015 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 26209922]

Mikles MR, Stchur RP, Graziano GP. Posterior instrumentation for thoracolumbar fractures. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2004 Nov-Dec:12(6):424-35 [PubMed PMID: 15615508]

Eberhardt CS, Zand T, Ceroni D, Wildhaber BE, La Scala G. The Seatbelt Syndrome-Do We Have a Chance?: A Report of 3 Cases With Review of Literature. Pediatric emergency care. 2016 May:32(5):318-22. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000527. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26087444]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence