Introduction

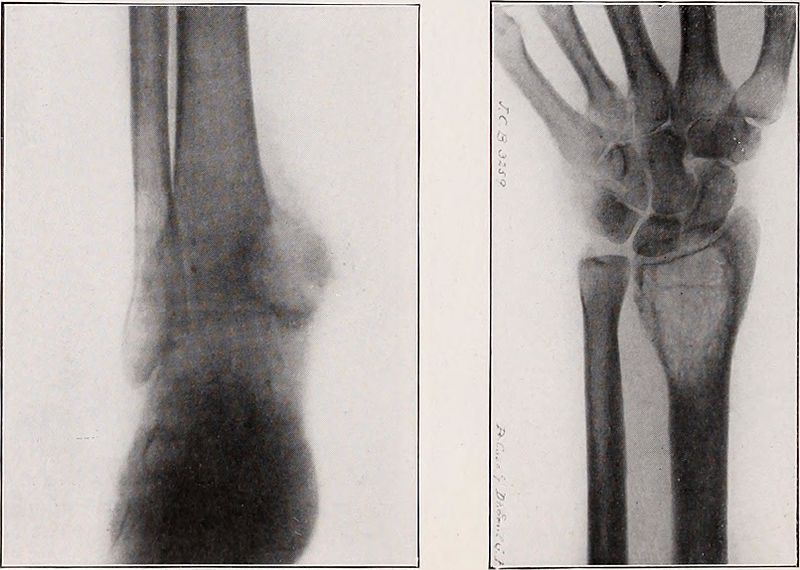

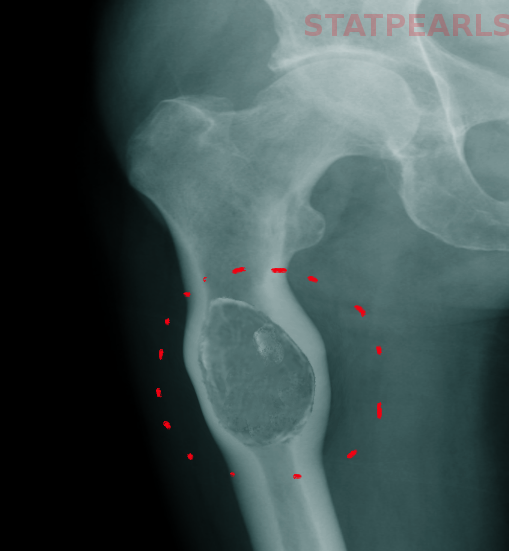

Bone cysts are often asymptomatic and found incidentally on radiographs (see Image. Tuberculosis Benign Bone Cyst, Radius, Ulnar). Sometimes, they may present with pain due to repeated hemorrhages or pathological fractures. Bone cysts include but are not limited to simple/unicameral bone cysts (SBC/UBC) and aneurysmal bone cysts (ABC). A simple bone cyst is a solitary, fluid-filled, benign bone cyst that may be unicameral (single chamber) or septated. It can involve any bone of extremities, the most common site being the proximal humerus and proximal femur (see Image. Bone Cyst in Proximal Femur).[1] In adults, the ilium and calcaneus are common locations. These lesions are most active during growth spurts and are known to heal spontaneously after bone maturity. Two-thirds of UBCs present with a fracture. UBCs in flat bones are often asymptomatic unless detected incidentally on imaging. An aneurysmal bone cyst is a rare, locally destructive, blood-filled, benign cystic bone tumor. It involves the metaphysis of long bones in children and young adults.[2] They can involve any bone, but the most common sites are the distal femur, proximal tibia, proximal humerus, and spine. Most cases present with mild to moderate pain. The rapid growth of lesions may mimic malignancy. Spinal lesions may cause radicular pain or neurologic deficits. They often involve posterior elements of the vertebral bodies. Exceptionally, ABC can also arise in soft tissue. See Image. Ankle Radiograph, Aneurysmal Bone Cyst (ABC).

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

UBC seems to be a reactive bone lesion rather than a true bone tumor. It forms secondary to venous stasis in cancellous bone. Bone resorption occurs secondary to venous stasis, pressure buildup, and increased inflammatory mediators in cyst fluid.[1]

ABC is a locally aggressive indeterminate tumor. It was thought to be caused by intraosseous hemorrhage because of venous stasis and bone resorption due to the activation of osteoclasts. However, this is no longer the accepted theory for primary ABC. Approximately 70% of primary ABC lesions are associated with recurrent chromosomal translocations causing gene fusions between ubiquitin-specific peptidase 6 (USP6) and multiple genes.[3] Secondary ABC has correlations with many benign and malignant primary bone lesions like chondroblastoma, osteosarcoma, simple bone cysts, giant cell tumors, and telangiectatic osteosarcoma. These secondary ABC lesions lack chromosomal translocations.[4]

Epidemiology

UBC is a common lesion. Most commonly, these lesions occur during the second decade of life (approximately 85%), with a male-to-female ratio of 2 to 1.

ABC is rarer, at 1.4 per 10000 population annually, and accounts for 9.1% of all bone tumors.[5] There is a female preponderance, and 80% of these lesions occur in the second decade. Most occur in patients younger than 20 years. It is rare after 30 years of age.

Pathophysiology

Unicameral bone cyst: Typically, these lesions arise near the physis. As the years progress, it gradually grows away from the physis and may remain a static bone defect in the diaphysis or resolve completely with time. The most favored hypothesis for cyst formation is venous flow blockage, which occurs in rapidly growing and remodeling bone. There are reports of a reduced partial pressure of oxygen in bone cysts as compared to arterial and venous blood, which further supports the hypothesis of venous stasis.[6] Aneurysmal bone cyst: ABC can show 3 different forms of evolutivity: quiescent, active, and aggressive. In some cases, ABC may undergo spontaneous resolution, while in others, they may become more aggressive, mimicking fears of malignancy. Primary: Comprising 70% of cases, ABC arises de-novo. Secondary: In the other 30% of cases, ABC occurs in underlying bone tumors like giant cell tumors, simple bone cysts, chondroblastomas, osteoblastoma, fibrous dysplasia, non-ossifying fibroma, and chondromyxoid fibromas.[1] The classification and staging of ABC are according to morphological characteristics and behavior of lesions.

Enneking staging for benign bone tumors according to the behavior of lesion[7]:

- Inactive form: most benign, expansion is rare, minimal inflammation

- Active: Expansile lesion with cortical thinning, reactive bone formation, mild pain clinically

- Aggressive: Rapidly expansile, destructive, severely symptomatic

Capanna morphologic types of aneurysmal bone cyst[8]:

- Type 1: Central well contained a metaphyseal lesion

- Type 2: Lesion involving an entire segment of bone with cortical expansion and thinning

- Type 3: Eccentric metaphyseal lesion with no or minimal cortical expansion

- Type 4: Subperiosteal reaction with no or minimal cortical erosion

- Type 5: Periosteum displaced with the erosion of cortex and extension into cancellous bone

Histopathology

UBC: Grossly, cyst fluid appears clear yellow and serous unless there is a pathological fracture causing bleeding. Cyst fluid contains inflammatory mediators like prostaglandin, free radicals, interleukins, metalloproteins, and cytokines. The cyst wall lacks epithelial lining and forms from the fibrovascular stroma. Deep in this membrane lie fragments of immature bone, osteoclast giant cells, and mesenchymal cells. Fracture thickens the cyst wall with fibroblast, hemosiderin, and reactive woven bone. Calcified cementum-like material in the cyst wall is found to be immature bone on immunohistochemistry.[9] ABC: Grossly, ABC is a blood-filled cavitary lesion with septations surrounded by a thin layer of cortical bone. Microscopically, it shows hemorrhagic tissue with cavernous spaces and cellular stroma. The lining consists of compressed fibroblasts and histiocytes. The fluid contains chronic inflammatory cells, prostaglandins, and giant cells. A solid variant of ABC, giant cell reparative granuloma, is also known.

History and Physical

UBC is often asymptomatic. Incidentally detected UBC in the femur or humerus is common. On occasions, pain can arise due to spontaneous fracture through the cyst. ABC: Long bones and spine are mostly involved. Mild to moderate pain, present for weeks to months, is the most common symptom that brings patients to the clinic.[10] Spinal lesion presents with back pain, scoliosis or torticollis. Soft tissue swelling may be present. Sometimes, the patient presents with a fracture. Physical examination shows tenderness, local swelling, and torticollis/scoliosis or neurological deficits in case of a spine cyst.

Evaluation

UBC:

Plain Radiograph: Well-marginated, metaphyseal, juxtaepiphyseal, central cystic, purely lytic, moderately expansile lesions along the long axis of the long bone are usually diagnostic of UBC. The cyst never causes a cortical breach; prominent inner wall cortical ridges may give it a multiloculated appearance. There is no periosteal reaction. In case of fracture, there may be a small cortical fragment on the floor of the cyst called a fallen fragment sign, which is considered pathognomonic of UBC with a fracture. UBC starts as a metaphyseal lesion abutting the epiphysis in children. With time, it moves into diaphysis. The lesion is considered as active when it is within 1 cm of the physis and stable when closer to the diaphysis. CT: shows thick-walled cysts with pseudoseptations. It is useful in assessing cyst fracture risk and imaging adjacent involved structures. MRI shows T2 hyperintense cysts and gadolinium enhancement of cyst wall and septa. Bone scintigraphy and positron emission tomography are inconclusive. Cystography is done to study venous drainage within the cyst.

ABC:

Primary Diagnosis: Suspect ABC on clinical examination and imaging:

Imaging characteristics: Radiograph reveals an expansile lytic, eccentric metaphyseal lesion that remains contained by a thin cortical wall. The cyst can be well-marginated or mildly permeative, mimicking malignancy. A smooth periosteal reaction usually covers the cyst. Bone scan shows peripheral tracer uptake and a central area of decreased uptake called the "doughnut sign." CT and MRI further help in delineating cyst characteristics, soft tissue involvement, and the aggressiveness of a tumor. CT is particularly useful in delineating cysts in areas like the spine and pelvis. When differentiating UBC and ABC on MRI, the presence of the double-density fluid and intralesional septations indicates ABC. Imaging further helps in planning surgical management.

Diagnosis: A biopsy should be performed in all cases for confirmation[2]. An optimal biopsy specimen is necessary for diagnosis. However, fine needle aspiration cytology is performed at some facilities by radiologists, which is often inconclusive. The indication for biopsy is high clinical and radiological suspicion for ABC. Uncorrected coagulopathy disorders are relative contraindications.

Treatment / Management

UBC: Nonoperative management is the choice for mild symptoms. Small asymptomatic lesions in the upper extremities are usually followed up with serial plain radiographs. Larger lesions at risk for fracture, symptomatic, and lower extremity lesions typically receive treatment with curettage or aspiration and injection (corticosteroids, bone marrow aspirates, bone matrix, and other materials). Pathological fractures in the upper extremity generally have conservative treatment. The priority of therapy is to treat the fracture first, typically by immobilization for 4 to 6 weeks. However, treatment involves fracture fixation and bone cyst treatment for unstable fractures or fractures in weight-bearing areas like the lower extremities.[11]

Treatment of all the other lesions is via non-aggressive options and techniques associated with preventive osteosynthesis. Injection of corticosteroids is 1 such option. The cyst is punctured with 2 needles, and its contents are aspirated with 1 needle. Radiological contrast is injected with the other, followed by injection with methylprednisone after emptying the contents. This also helps to differentiate from ABC. Cryptographic assessment showing the absence of venous drainage in the cyst rather than the presence of rapid venous outflow is a good prognostic indicator for treatment outcome, with the former showing better cyst healing.[12] This technique works by either its antiprostaglandin effect or by decreasing intracystic pressure. It demonstrates a success rate of more than 90%. Bone marrow aspirate and demineralized bone matrix injection avoid open bone curettage, and grafting in 78% of cases with proximal humerus UBC can be considered an adjuvant to curettage.[13] Elastic stable intramedullary nailing in the case of long bones of children has shown promising results for treating UBC.[14] Current treatment concepts include a combination of decompressions, cyst wall disruption, injection with corticosteroid/demineralized bone matrix/bone marrow aspirate, and internal fixation in the weight-bearing region.[15] Diagnosis is either incidental or prompted by a fracture. ABC and underlying malignancy must be ruled out in both scenarios before further management.(B2)

ABC: The treatment goal for ABC is the eradication of disease, prevention of recurrence, and reduction of pain/ functional impairment. Surgical curettage and bone grafting with or without adjuvant therapy were classically the primary modes of treatment. However, the need for wide resection, disability, cost of rehabilitation post-surgery, and the benign nature of the cyst have prompted the search for less aggressive treatment options.

Several minimally invasive treatments have emerged as an alternative to curettage, including sclerotherapy with polidocanol, selective embolization of feeding vessel to the cyst, and medical therapy with denosumab. Radionuclide ablation is also an option.[16][17] Preoperative embolizations also help to minimize surgical bleeding for lesions involving the spine and pelvis. When curettage is impossible due to difficult anatomy, arterial embolization can be an option. Low-dose radiation can cause rapid ossification of the lesion. However, it is less popular due to the risk of malignant transformation. However, it is sometimes used in surgically inaccessible recurrent spinal tumors. Percutaneous injection of calcitonin and steroids under CT guidance has shown positive results. Repeated recurrences or development of any suspicious findings on imaging necessitate a more aggressive treatment.[18] Injection with an alcoholic solution of zein (corn protein), which possesses thrombogenic and fibrogenic properties, is a simple alternative; it makes open surgical treatment unnecessary by stopping the cyst growth and inducing new bone formation along the inner endosteal layer of the cyst.[19] Absolute alcohol also shows comparable treatment efficacy with a low complication rate. It may require repeated injections.(B3)

Differential Diagnosis

1. UBC and ABC affect the same age group, have similar sites, and are fluid-filled cystic lesions, making diagnosis difficult. However, ABC is more eccentric and aggressive and shows increased trabeculations, which helps differentiate it from UBC. Even so, traumatized UBC can be difficult to diagnose from primary ABC. In this case, a biopsy can be helpful; areas of cement-like substance indicate UBC, while calcifying bluish fibrochondroid areas indicate ABC.[20]

2. Telangiectatic Osteosarcoma: These lesions show similar features as ABC radiographically. A biopsy is particularly essential to rule out osteosarcoma. Atypical cells, mitosis, and irregular osteoid matric are features of telangiectatic osteosarcoma. Molecular biology, using fluorescence in situ hybridization, shows the rearrangement of USP6 in primary ABC.[1]

3. Giant Cell Tumor

4. Eosinophilic granuloma, osteoblastoma, malignant tumors

5. Nonossifying fibroma and solid ABC could appear similar

Other cystic bone lesions:

Intraosseous ganglion cysts: These typically occur at the ends of the long bones, particularly the distal tibia, knee, and shoulder. On X-rays, they appear as well-marginated, unilocular, or multilocular lytic defects with a thin rim of sclerosis. Treatment involves local excision and curettage.

Epidermoid cyst: These cystic lesions are filled with keratinous material and lined with squamous epithelium.

Prognosis

UBC: UBC develops in the metaphysis and gradually grows away from the physis. It is known for spontaneous resolution, as evidenced by its rareness in adults.

Active cysts are very near the growth plate, while inactive cysts have grown away from growth or are not in direct contact with the growth plate.[21] High-risk areas are those that may lead to significant disability, like a femur neck cyst, which, if fractured, may lead to necrosis and limb length discrepancy. Asymptomatic lesions with a low risk for pathological fractures/inactive cysts are usually left alone. Most children present with pain due to pathological fractures through cysts. Growth discrepancy may occur due to cyst pressure into growth plates, as a complication of cyst treatment near the growth plate, or a fracture through a femoral neck cyst. All these may cause limb length discrepancy and deformities. Hence, the appropriate treatment protocol is crucial for the management of cysts. Curettage and bone grafting with internal fixation are reserved for larger, symptomatic lesions in high-risk areas like the femur. Other lesions are treated with percutaneous injections, as described above. Poor prognostic factors for recurrence following percutaneous treatment include large size, multilocation, active lesions, and age younger than 10.

ABC: The recurrence rate after curettage of ABC is approximately 10 to 20%. Age younger than 15 years, central location, and incomplete removal of the cystic cavity are known risk factors for recurrence. Complete surgical resection is reserved for more dispensible bones like the clavicle and fibula, where partial bone excision does not cause any significant long-term morbidity.

Complications

The following complications may accompany these lesions:

- Pathological fracture: The main complication of SBC is a fracture. Pain, younger age of presentation, proximal humeral lesion, change in the size of a cavity with age, distance from growth plate, multiple septations, and early recurrence are signs of an active cyst and increased fracture risk

- Pain

- Malignant transformation is rare in UBC. Rare cases of malignancies have been reported several years after the treatment of ABC

- Arthritis

- Pressure symptoms

- Growth disorder: Limb length discrepancy or axial deviation may be induced in children if cysts transgress the physis or involve the epiphysis

- Recurrence: No treatment guarantees complete cure except for complete surgical resection - the post-treatment recurrence rate in the case of UBC is about 10 to 30%; hence, the least aggressive treatment is the initial option

- Aggressive surgical treatment for femoral neck lesions has generally been advocated, given the dreaded complications associated with pathological femur neck fractures (like avascular necrosis, residual coxa vara, etc).

- General risks related to the management of cysts: Unanticipated residual structural deformity and functional disability and injury to adjacent vital structures (eg, neurovascular) can occur[1][22][1]

Deterrence and Patient Education

It is of extreme importance to educate the patients and primary caregivers in the case of pediatric patients regarding the benign course of the tumor and what to expect with regard to deformity, disability, complications, and recurrence following treatment. The parents should also receive counsel regarding different treatment options and the risks and benefits of these treatment modalities. The role of patient counseling and family support in ensuring appropriate healthcare delivery to these patients cannot be understated. Pathological fractures: Pathological fracture is present in approximately 75% of cases of UBC at the time of presentation (which is, in fact, the most common cause of pathological fracture in children).[23][24] Mirels criteria predict a high risk of pathological fracture among long bones in case of lytic/sclerotic lesions (typically malignant pathologies). It consists of the following components: site, location, matrix, and presence or absence of pain. It has a minimum score of 4 and a maximum score of 12. A score of more than 9 suggests the necessity of prophylactic fixation.[25] Mirels criteria can be useful in predicting fracture risk in the bone cyst and in planning appropriate management by the health care team.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Good knowledge of clinical/radiological presentations of bone cysts and possible distinguishing features from other bone tumors presenting as lytic lesions of the bone is of utmost importance in appropriate medical planning and management of these lesions. Although orthopedic surgeons play a pivotal role in managing these patients, appropriate inputs from pediatricians, family physicians, radiologists, pathologists, orthopedic surgeons, and physiotherapists are necessary at different management stages. Nurse practitioners are involved in home care management when pathological fractures are managed conservatively. Inter-departmental cooperation and planning of treatment protocols in consultation with patients, physicians, nurses, and social workers enhance team performance and patient care.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Mascard E, Gomez-Brouchet A, Lambot K. Bone cysts: unicameral and aneurysmal bone cyst. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2015 Feb:101(1 Suppl):S119-27. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.031. Epub 2015 Jan 8 [PubMed PMID: 25579825]

Rapp TB, Ward JP, Alaia MJ. Aneurysmal bone cyst. The Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2012 Apr:20(4):233-41. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-20-04-233. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22474093]

Warren M, Xu D, Li X. Gene fusions PAFAH1B1-USP6 and RUNX2-USP6 in aneurysmal bone cysts identified by next generation sequencing. Cancer genetics. 2017 Apr:212-213():13-18. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2017.03.007. Epub 2017 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 28449806]

Oliveira AM, Perez-Atayde AR, Dal Cin P, Gebhardt MC, Chen CJ, Neff JR, Demetri GD, Rosenberg AE, Bridge JA, Fletcher JA. Aneurysmal bone cyst variant translocations upregulate USP6 transcription by promoter swapping with the ZNF9, COL1A1, TRAP150, and OMD genes. Oncogene. 2005 May 12:24(21):3419-26 [PubMed PMID: 15735689]

Cottalorda J, Bourelle S. Current treatments of primary aneurysmal bone cysts. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. Part B. 2006 May:15(3):155-67 [PubMed PMID: 16601582]

Chigira M, Maehara S, Arita S, Udagawa E. The aetiology and treatment of simple bone cysts. The Journal of bone and joint surgery. British volume. 1983 Nov:65(5):633-7 [PubMed PMID: 6643570]

Enneking WF. A system of staging musculoskeletal neoplasms. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 1986 Mar:(204):9-24 [PubMed PMID: 3456859]

Capanna R, Bettelli G, Biagini R, Ruggieri P, Bertoni F, Campanacci M. Aneurysmal cysts of long bones. Italian journal of orthopaedics and traumatology. 1985 Dec:11(4):409-17 [PubMed PMID: 3830963]

Tariq MU, Din NU, Ahmad Z, Kayani N, Ahmed R. Cementum-like matrix in solitary bone cysts: a unique and characteristic but yet underrecognized feature of promising diagnostic utility. Annals of diagnostic pathology. 2014 Feb:18(1):1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2013.07.001. Epub 2013 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 24090508]

Mankin HJ, Hornicek FJ, Ortiz-Cruz E, Villafuerte J, Gebhardt MC. Aneurysmal bone cyst: a review of 150 patients. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2005 Sep 20:23(27):6756-62 [PubMed PMID: 16170183]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceWilke B, Houdek M, Rao RR, Caird MS, Larson AN, Milbrandt T. Treatment of Unicameral Bone Cysts of the Proximal Femur With Internal Fixation Lessens the Risk of Additional Surgery. Orthopedics. 2017 Sep 1:40(5):e862-e867. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20170810-01. Epub 2017 Aug 18 [PubMed PMID: 28817159]

Ramirez A, Abril JC, Touza A. Unicameral bone cyst: radiographic assessment of venous outflow by cystography as a prognostic index. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. Part B. 2012 Nov:21(6):489-94. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0b013e328355e5ba. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22751482]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGundle KR, Bhatt EM, Punt SE, Bompadre V, Conrad EU. Injection of Unicameral Bone Cysts with Bone Marrow Aspirate and Demineralized Bone Matrix Avoids Open Curettage and Bone Grafting in a Retrospective Cohort. The open orthopaedics journal. 2017:11():486-492. doi: 10.2174/1874325001711010486. Epub 2017 May 31 [PubMed PMID: 28694887]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencede Sanctis N, Andreacchio A. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing is the best treatment of unicameral bone cysts of the long bones in children?: Prospective long-term follow-up study. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. 2006 Jul-Aug:26(4):520-5 [PubMed PMID: 16791072]

Donaldson S, Wright JG. Recent developments in treatment for simple bone cysts. Current opinion in pediatrics. 2011 Feb:23(1):73-7. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283421111. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21191299]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTsagozis P, Brosjö O. Current Strategies for the Treatment of Aneurysmal Bone Cysts. Orthopedic reviews. 2015 Dec 28:7(4):6182. doi: 10.4081/or.2015.6182. Epub 2015 Dec 28 [PubMed PMID: 26793296]

Lange T, Stehling C, Fröhlich B, Klingenhöfer M, Kunkel P, Schneppenheim R, Escherich G, Gosheger G, Hardes J, Jürgens H, Schulte TL. Denosumab: a potential new and innovative treatment option for aneurysmal bone cysts. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 2013 Jun:22(6):1417-22. doi: 10.1007/s00586-013-2715-7. Epub 2013 Mar 1 [PubMed PMID: 23455951]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChang CY, Kattapuram SV, Huang AJ, Simeone FJ, Torriani M, Bredella MA. Treatment of aneurysmal bone cysts by percutaneous CT-guided injection of calcitonin and steroid. Skeletal radiology. 2017 Jan:46(1):35-40 [PubMed PMID: 27743037]

George HL, Unnikrishnan PN, Garg NK, Sampath JS, Bass A, Bruce CE. Long-term follow-up of Ethibloc injection in aneurysmal bone cysts. Journal of pediatric orthopedics. Part B. 2009 Nov:18(6):375-80. doi: 10.1097/BPB.0b013e32832f724c. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19657285]

Weber M, Hillmann A. [Bone cysts-differential diagnosis and therapeutic approach]. Der Orthopade. 2018 Jul:47(7):607-618. doi: 10.1007/s00132-018-3586-8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29947874]

Norman A, Schiffman M. Simple bone cysts: factors of age dependency. Radiology. 1977 Sep:124(3):779-82 [PubMed PMID: 887773]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceCottalorda J, Bourelle S. [Aneurysmal bone cyst in 2006]. Revue de chirurgie orthopedique et reparatrice de l'appareil moteur. 2007 Feb:93(1):5-16 [PubMed PMID: 17389819]

Jackson WF, Theologis TN, Gibbons CL, Mathews S, Kambouroglou G. Early management of pathological fractures in children. Injury. 2007 Feb:38(2):194-200 [PubMed PMID: 17054958]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceOrtiz EJ, Isler MH, Navia JE, Canosa R. Pathologic fractures in children. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2005 Mar:(432):116-26 [PubMed PMID: 15738811]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceJawad MU, Scully SP. In brief: classifications in brief: Mirels' classification: metastatic disease in long bones and impending pathologic fracture. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2010 Oct:468(10):2825-7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1326-4. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20352387]