Introduction

Mycobacterium kansasii is a non-tuberculosis mycobacterium (NTM) that is readily recognized based on its characteristic photochromogenicity; it produces a yellow pigment when exposed to light.

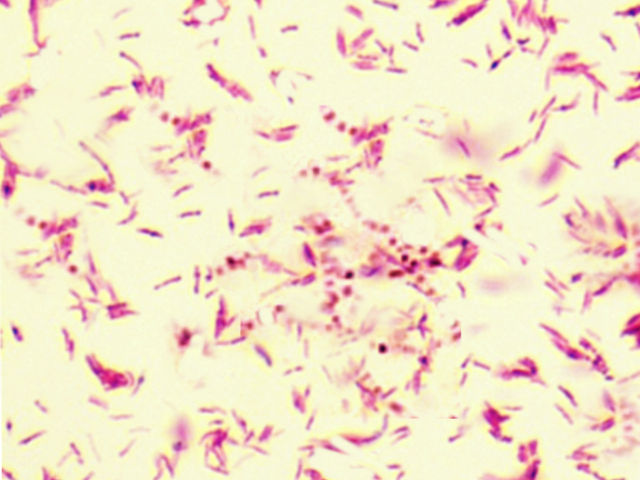

Buhler and Pollack first described this slow-growing mycobacterium in 1953.[1] Under light microscopy, M. kansasii appears as thick rectangular, beaded, gram-positive rods which are longer than those of M. tuberculosis.[2] Clinically, M. kansasii causes a chronic, upper-lobe cavitary disease, resembling that from M. tuberculosis. The prevalence of NTM infections has steadily increased when compared to tuberculosis whose prevalence has decreased in the last few decades.[3] There is no clear data regarding the prevalence of M. kansasii, although some studies have in fact shown decreasing prevalence.[4]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Mycobacterium Kansasii is a slow-growing acid-fast bacillus. It grows best at 32 degrees Celcius, but can be cultured at 37 degrees. Its in-vitro and chemical characteristics are similar to those of M. marinum and M. szulgai . It produces mature colonies in greater then 7 days. Like other mycobacteria in the family, M. kansasii is strictly a gram-positive, non-motile and non-spore-forming organism. Colony morphology ranges from flat to raised and smooth to rough. When grown in the dark M. kansasii colonies are at first non-pigmented but turn yellow after exposure to light due to deposition of beta-carotene crystals.[5] Microscopic examinations show that when compared to M. tuberculosis, M. kansasii appears longer and broader and are often beaded or cross-barred in appearance when stained with Ziehl Neelsen or Kinyoun stain.[6] In Runyon classification, M. kansasii belongs to the group photochromogens. Biochemical characteristics include Catalase positive, nitrate reduction, tween hydrolysis, and urea hydrolysis. Identification using traditional methods could take as long as two months.

Although M. Kansasii was long thought to be homogenous species, genetic studies have shown that there are at least seven subtypes, with subtype one being most frequently isolated in human infections.[7] Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis techniques demonstrate that the clinical isolates are very closely related and may be clonal worldwide. Clinical isolates from Japan are similar those from Europe and USA. Pathogenic strains are highly Catalase positive.

M. kansasii is widely prevalent in the environment but has seldom been isolated from soil. Some documented sources include city tap water, swimming pools, fish tanks, fish bites, brackish water, and seawater.[8] Tap water appears to be the major reservoir. Infection is mostly acquired through the aerosol route. Infectivity is low in regions of endemicity. Transmission from humans to humans is not thought to occur, except in two cases where familial clustering was noted.[9] Clustering was thought to be due to a shared environment, susceptibility or genetic predisposition rather than true human to human transmission.[10]

Epidemiology

M. kansasii infection mostly occurs in males, at an average patient age of 45–62 years.[11] Lung infections caused by M. kansasii occur in geographic clusters.[12] In the United States, M. kansasii infections are more common in southern and central states with the highest incidence seen in the southern states of Texas, Louisiana and Florida, as well as the central states of Illinois, Kansas, and Nebraska. M. kansasii infections are more likely to occur in urban areas than rural areas, and several studies have reported an association with mining practices.[13] In the United Kingdom, M. kansasii infections are most frequent in Wales. Of all countries in Europe, Poland has the highest M. kansasii isolation rate (35% of all NTM compared to 5% in Europe).[4][14][4]

M. kansasii infections are also prevalent in areas where HIV infection is common due to the susceptibility of the hosts.

M. kansasii infections were the most common non-tuberculosis mycobacterial infections during the 1960s and 70s, before being surpassed by M. avium-intracellulare. In the 80s with the rise of HIV infections, there was a resurgence of M. kansasii, which has now decreased in the antiretroviral therapy (AR) era. M. kansasii infections can occur in both immunocompetent and immunosuppressed patients.[15][16] In the 1980s the overall prevalence of M. kansasii infections was estimated to be 0.5 cases per 100,000 persons. Since mycobacterial infections are not reported, there is no reliable data for M. kansasii infections in transplant patients. Generally in transplant patients mycobacterial infections present as disseminated infections.[17] Fifty percent of patients with pulmonary disease also have dissemination. Renal transplant patients have been the most frequently reported to have disseminated disease. M. abscesses, M. chelonae, and M.kansasii are the mycobacteria most commonly present with dissemination. Even in HIV and late-stage AIDS patients, M. kansasii presents with pulmonary disease. In one study from California, the prevalence of mycobacterial infections was 0.75 /100 000 in HIV-negative patients, 115/100000 in HIV-positive patients, and 647/100000 persons in AIDS patients.[18][19]

History and Physical

Mycobacterial infections, including M. kansasii infections, can be categorized into six clinical patterns: pulmonary disease, skin, and soft tissues, musculoskeletal infections (monoarticular septic arthritis and tenosynovitis), disseminated disease, catheter-associated disease, and lymphadenitis.[20] Chronic pulmonary cavitary disease in the upper lobe is the most common presentation of M. kansasii infections. Not surprisingly these patients may be initially diagnosed with pulmonary tuberculosis. In one study, the mean age of patients with M. kansasii infection was 58 years, and 64% were men. However, M. kansasii can infect adults of any age, sex, or race. Infection results in symptoms in 85% of cases.

The most common symptoms of pulmonary M. kansasii infection include a cough (91%), sputum production (85%), weight loss (53%), breathlessness (51%), chest pain (34%), hemoptysis (32%), and fever or sweats (17%). Of all the NTM infections, M. kansasii infections most often resemble Mycobacterial tuberculosis infections.[21] Risk factors for M. kansasii infections are the same as those for other mycobacteria, namely, smoking, pneumoconiosis, silicosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, malignancy, immunosuppressed state, chronic kidney disease, alcoholism and concurrent or prior M. tuberculosis infection.[3]

While cavitary disease occurs in 90% M. kansasiiI infections, nodular and brochiectatic disease can also occur. If left untreated pulmonary infections (both cavitary and nodular) are characterized by the persistence of AFB in the sputum and progressive destruction of the lung architecture. Pulmonary disease may be present in AIDS patients but there is less likelihood of cavitations; hilar lymphadenopathy and interstitial infiltrates are more common. However, if the CD4 count is high there is an increased chance of cavitary disease.

The second most frequent organ involved in M. kansasii infection is the skin.[22] Cutaneous infection resembles secondary to local lymphatic spread. Cutaneous lesions may include nodules, pustules, verrucous lesions, erythematous plaques, abscesses, and ulcers. In HIV and immunocompromised patients, the presentation can be atypical and include bacteremia, osteomyelitis, abscesses, and cellulitis. Pericarditis with cardiac tamponade has been reported in HIV patients.[23]

In disseminated disease, the symptoms are vague and nonspecific. In a series of 49 patients, fever was present in 60%, hepatosplenomegaly in 40%; pulmonary infiltrates in 25% and lymphadenopathy in 10%. Bone involvement, such as vertebral osteomyelitis and sacroiliitis, is common with M. kansasii disseminated diseases. Psoas abscess, bone marrow granuloma, liver granuloma, and possible spleen abscesses have been described.

In patients with an advanced immunocompromised state, HIV and M. kansasii co-infection can occur and reported average CD count in these patients has been less than <50/mm3.[24]

Evaluation

Since the symptoms are not specific and the differential diagnosis is broad, microbiologic isolation is required to make the diagnosis. M. kansasii rarely represents colonization or environmental contamination. Therefore any isolation of the organism needs to be evaluated for therapy.[25] Highly sensitive and specific PCR tests are available for M. kansasii.[26][25]

Culture results along with clinical and radiological diagnosis are recommended for accurate diagnosis of M. kansasii. As per the guidelines from ATS (American Thoracic Society) and IDSA (Infectious Disease Society of America) diagnosis of NTM should include a minimal radiological evaluation which includes a chest X-ray (or computed tomography of the chest if there is an absence of cavitation), combined with positive sputum cultures and exclusion of other diagnoses clinically. Cultures are considered positive when two consecutive positive sputum cultures, one positive culture from bronchoscopy specimens, or one positive sputum culture with compatible pathology is present.[25] Cultures are considered to be positive when a) 2 sputum cultures are consecutively positive, b) bronchoscopy specimens with one positive culture or c) one sputum culture is positive and a compatible pathology is present.[25]

Treatment / Management

Rifampin is the cornerstone of M kansasii therapy. The first line therapy recommended by IDSA-ATS guidelines for M. kansasii is rifampin, ethambutol, and isoniazid plus pyridoxine.[27][28][29] The recommended duration of therapy is at least 12 months or more with the goal to have culture negative results for 12 months on therapy. M. kansasii are predictably resistant to pyrazinamide. Isoniazid (INH) resistance should be interpreted with caution as a higher concentration is needed for M. kansasii when compared to M. tuberculosis. M. kansasii organisms show resistance to isoniazid at one mcg/mL but are susceptible at five mcg/mL. In a treatment naïve patient, INH is effective regardless of concentration achieved in the serum. Rifampin-containing regimens have low failure rates (1.1%) and low long-term relapse rates (< 1%). Based on M. kansasii susceptibilities in vitro, patients with rifampin-resistant M kansasii disease should be treated with a 3-drug regimen, which should include clarithromycin or azithromycin. The other two drugs should be chosen from moxifloxacin, ethambutol, sulfamethoxazole, or streptomycin.[3] The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) recommends that all initial isolates of M. kansasii be tested only for clarithromycin and rifampin susceptibility. INH and streptomycin susceptibility should be tested as secondary agents.(B2)

M. kansasii in HIV patients:

One strategy to treat M. kansasii infection in HIV-positive patients is to use an NRTI-based regimen, allowing for a full dose of rifampin, which is the cornerstone of therapy for M. kansasii. If a protease inhibitor (PI) such as darunavir or atazanavir or non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor [NNRTI] such as efavirenz or nevirapine is included in HIV treatment regimens, rifabutin can be used instead of rifampin. Clarithromycin can be added to improve efficacy, but rifabutin-related toxicity can increase when combined with clarithromycin.

Monitoring therapy:

Serial sputum samples for AFB should be obtained regularly so patients failing therapy are recognized early and susceptibility testing for additional drugs can be done. Serial CXR can be administered, although lung disease is likely to evolve at a slow pace. Routine monitoring for adverse effects of medications and drug-drug interactions is recommended.

Differential Diagnosis

- Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- NTM other such as MAC

- Endemic fungi

- Actinomyces group

- Cancer

- Wegener’s

Prognosis

With appropriate treatment, the prognosis is usually good.[30] Mortality is higher and can go up to 50% in patients with HIV who have M. kansasii infection.[24] In HIV patients who have a pulmonary infection with M. kansasii, survival predictors include higher CD4 cell count, negative smear microscopy, antiretroviral therapy and adequate treatment for M. kansasii.[24]

Complications

Complications can include disseminated disease. Bone involvement, such as vertebral osteomyelitis and sacroiliitis are common with disseminated diseases.[31] Pneumothorax, Psoas abscess, bone marrow granuloma, liver granuloma, and possible spleen abscesses have also been described in the literature.[32] CNS complications like meningoencephalitis are very rare and are usually fatal.

Consultations

Pulmonology

Infectious disease

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients should know that the prognosis of M. kansasii is usually good when recognized and treated early. Treatment duration is long and the patients should adhere to the duration of the treatment as relapse rates are high if treatment is stopped early.

Pearls and Other Issues

Treatment is prolonged and requires meticulous monitoring, but M. kansasii is a treatable infection. With rifampin-based regimens, the relapse rate is very low, and the prognosis is good. A study of 302 patients followed over more than a 50-year period (1952-1995), showed a mortality rate of 11%, but this included both immunocompromised and non-immunocompromised patients.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Management of M. kansasii requires an interprofessional effort from primary care physicians, pulmonologists and infectious disease specialists. Physicians and nurses should educate the patient about being compliant with their medications. Ethambutol can cause visual disturbances. Rifampin is a strong CYP3A4 Inducer and may decrease the serum concentrations or decrease the therapeutic effect of most multiple medications. Pharmacists should be aware of the drugs the patients are on and also explain to the patients about the side effects of medications used in the management of M. kansasii.

Media

References

BUHLER VB, POLLAK A. Human infection with atypical acid-fast organisms; report of two cases with pathologic findings. American journal of clinical pathology. 1953 Apr:23(4):363-74 [PubMed PMID: 13040295]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTsukamura M. [A review on the bacteriology of Mycobacterium kansasii]. Kekkaku : [Tuberculosis]. 1984 Nov:59(11):563-7 [PubMed PMID: 6394864]

Maliwan N, Zvetina JR. Clinical features and follow up of 302 patients with Mycobacterium kansasii pulmonary infection: a 50 year experience. Postgraduate medical journal. 2005 Aug:81(958):530-3 [PubMed PMID: 16085747]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHoefsloot W,van Ingen J,Andrejak C,Angeby K,Bauriaud R,Bemer P,Beylis N,Boeree MJ,Cacho J,Chihota V,Chimara E,Churchyard G,Cias R,Daza R,Daley CL,Dekhuijzen PN,Domingo D,Drobniewski F,Esteban J,Fauville-Dufaux M,Folkvardsen DB,Gibbons N,Gómez-Mampaso E,Gonzalez R,Hoffmann H,Hsueh PR,Indra A,Jagielski T,Jamieson F,Jankovic M,Jong E,Keane J,Koh WJ,Lange B,Leao S,Macedo R,Mannsåker T,Marras TK,Maugein J,Milburn HJ,Mlinkó T,Morcillo N,Morimoto K,Papaventsis D,Palenque E,Paez-Peña M,Piersimoni C,Polanová M,Rastogi N,Richter E,Ruiz-Serrano MJ,Silva A,da Silva MP,Simsek H,van Soolingen D,Szabó N,Thomson R,Tórtola Fernandez T,Tortoli E,Totten SE,Tyrrell G,Vasankari T,Villar M,Walkiewicz R,Winthrop KL,Wagner D, The geographic diversity of nontuberculous mycobacteria isolated from pulmonary samples: an NTM-NET collaborative study. The European respiratory journal. 2013 Dec [PubMed PMID: 23598956]

David HL. Biogenesis of beta-carotene in Mycobacterium kansasii. Journal of bacteriology. 1974 Aug:119(2):527-33 [PubMed PMID: 4850775]

Bainomugisa A, Wampande E, Muchwa C, Akol J, Mubiri P, Ssenyungule H, Matovu E, Ogwang S, Joloba M. Use of real time polymerase chain reaction for detection of M. tuberculosis, M. avium and M. kansasii from clinical specimens. BMC infectious diseases. 2015 Apr 14:15():181. doi: 10.1186/s12879-015-0921-0. Epub 2015 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 25884439]

Zhang Y, Mann LB, Wilson RW, Brown-Elliott BA, Vincent V, Iinuma Y, Wallace RJ Jr. Molecular analysis of Mycobacterium kansasii isolates from the United States. Journal of clinical microbiology. 2004 Jan:42(1):119-25 [PubMed PMID: 14715741]

Collins CH,Grange JM,Yates MD, Mycobacteria in water. The Journal of applied bacteriology. 1984 Oct [PubMed PMID: 6389461]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePenny ME, Cole RB, Gray J. Two cases of Mycobacterium kansasii infection occurring in the same household. Tubercle. 1982 Jun:63(2):129-31 [PubMed PMID: 7179479]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceColombo RE, Hill SC, Claypool RJ, Holland SM, Olivier KN. Familial clustering of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Chest. 2010 Mar:137(3):629-34. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1173. Epub 2009 Oct 26 [PubMed PMID: 19858235]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShitrit D, Baum GL, Priess R, Lavy A, Shitrit AB, Raz M, Shlomi D, Daniele B, Kramer MR. Pulmonary Mycobacterium kansasii infection in Israel, 1999-2004: clinical features, drug susceptibility, and outcome. Chest. 2006 Mar:129(3):771-6 [PubMed PMID: 16537880]

Adjemian J,Olivier KN,Seitz AE,Falkinham JO 3rd,Holland SM,Prevots DR, Spatial clusters of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in the United States. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2012 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 22773732]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidencevan Halsema CL, Chihota VN, Gey van Pittius NC, Fielding KL, Lewis JJ, van Helden PD, Churchyard GJ, Grant AD. Clinical Relevance of Nontuberculous Mycobacteria Isolated from Sputum in a Gold Mining Workforce in South Africa: An Observational, Clinical Study. BioMed research international. 2015:2015():959107. doi: 10.1155/2015/959107. Epub 2015 May 28 [PubMed PMID: 26180817]

Prevots DR, Marras TK. Epidemiology of human pulmonary infection with nontuberculous mycobacteria: a review. Clinics in chest medicine. 2015 Mar:36(1):13-34. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2014.10.002. Epub 2014 Nov 6 [PubMed PMID: 25676516]

Marras TK, Daley CL. A systematic review of the clinical significance of pulmonary Mycobacterium kansasii isolates in HIV infection. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2004 Aug 1:36(4):883-9 [PubMed PMID: 15220694]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceOhnishi T,Kusumoto S,Yamaguchi S,Ohki Y,Satou M,Sugiyama T,Shirai T,Nakashima M,Yamaoka T,Okuda K,Hirose T,Adachi M, [Three cases of Mycobacterium kansasii pulmonary diseases in previously healthy young women]. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai zasshi = the journal of the Japanese Respiratory Society. 2011 Jun [PubMed PMID: 21735743]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLillo M, Orengo S, Cernoch P, Harris RL. Pulmonary and disseminated infection due to Mycobacterium kansasii: a decade of experience. Reviews of infectious diseases. 1990 Sep-Oct:12(5):760-7 [PubMed PMID: 2237115]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBloch KC, Zwerling L, Pletcher MJ, Hahn JA, Gerberding JL, Ostroff SM, Vugia DJ, Reingold AL. Incidence and clinical implications of isolation of Mycobacterium kansasii: results of a 5-year, population-based study. Annals of internal medicine. 1998 Nov 1:129(9):698-704 [PubMed PMID: 9841601]

Sheu LC, Tran TM, Jarlsberg LG, Marras TK, Daley CL, Nahid P. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections at San Francisco General Hospital. The clinical respiratory journal. 2015 Oct:9(4):436-42. doi: 10.1111/crj.12159. Epub 2014 Jun 10 [PubMed PMID: 24799125]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBernard L,Vincent V,Lortholary O,Raskine L,Vettier C,Colaitis D,Mechali D,Bricaire F,Bouvet E,Sadr FB,Lalande V,Perronne C, Mycobacterium kansasii septic arthritis: French retrospective study of 5 years and review. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 1999 Dec [PubMed PMID: 10585795]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMatveychuk A, Fuks L, Priess R, Hahim I, Shitrit D. Clinical and radiological features of Mycobacterium kansasii and other NTM infections. Respiratory medicine. 2012 Oct:106(10):1472-7. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2012.06.023. Epub 2012 Jul 31 [PubMed PMID: 22850110]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRazavi B, Cleveland MG. Cutaneous infection due to Mycobacterium kansasii. Diagnostic microbiology and infectious disease. 2000 Nov:38(3):173-5 [PubMed PMID: 11109017]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCho JH, Yu CH, Jin MK, Kwon O, Hong KD, Choi JY, Yoon SH, Park SH, Kim CD, Kim YL. Mycobacterium kansasii pericarditis in a kidney transplant recipient: a case report and comprehensive review of the literature. Transplant infectious disease : an official journal of the Transplantation Society. 2012 Oct:14(5):E50-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2012.00767.x. Epub 2012 Jul 23 [PubMed PMID: 22823928]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMarras TK,Morris A,Gonzalez LC,Daley CL, Mortality prediction in pulmonary Mycobacterium kansasii infection and human immunodeficiency virus. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2004 Oct 1 [PubMed PMID: 15215152]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceGriffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, Holland SM, Horsburgh R, Huitt G, Iademarco MF, Iseman M, Olivier K, Ruoss S, von Reyn CF, Wallace RJ Jr, Winthrop K, ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee, American Thoracic Society, Infectious Disease Society of America. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2007 Feb 15:175(4):367-416 [PubMed PMID: 17277290]

Deggim-Messmer V, Bloemberg GV, Ritter C, Voit A, Hömke R, Keller PM, Böttger EC. Diagnostic Molecular Mycobacteriology in Regions With Low Tuberculosis Endemicity: Combining Real-time PCR Assays for Detection of Multiple Mycobacterial Pathogens With Line Probe Assays for Identification of Resistance Mutations. EBioMedicine. 2016 Jul:9():228-237. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.06.016. Epub 2016 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 27333026]

Griffith DE. Management of disease due to Mycobacterium kansasii. Clinics in chest medicine. 2002 Sep:23(3):613-21, vi [PubMed PMID: 12370997]

Griffith DE,Aksamit TR, Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease Therapy: Take It to the Limit One More Time. Chest. 2016 Dec [PubMed PMID: 27938739]

DeStefano MS, Shoen CM, Cynamon MH. Therapy for Mycobacterium kansasii Infection: Beyond 2018. Frontiers in microbiology. 2018:9():2271. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02271. Epub 2018 Sep 24 [PubMed PMID: 30319580]

Griffith DE, Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ Jr. Thrice-weekly clarithromycin-containing regimen for treatment of Mycobacterium kansasii lung disease: results of a preliminary study. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2003 Nov 1:37(9):1178-82 [PubMed PMID: 14557961]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencevan Herwaarden N, Bavelaar H, Janssen R, Werre A, Dofferhoff A. Osteomyelitis due to Mycobacterium kansasii in a patient with sarcoidosis. IDCases. 2017:9():1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.idcr.2017.04.001. Epub 2017 Apr 14 [PubMed PMID: 28529884]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBoo KY,Lee JH, A Case of Pulmonary Mycobacterium kansasii Disease Complicated with Tension Pneumothorax. Tuberculosis and respiratory diseases. 2015 Oct [PubMed PMID: 26508923]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence