Introduction

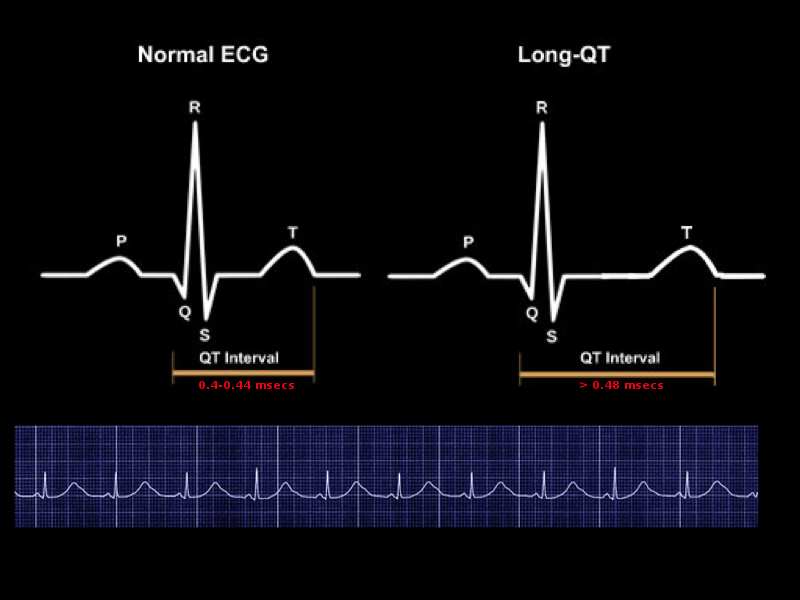

Jervell and Lange Nielsen syndrome (JLNS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by bilateral sensorineural hearing loss and a prolonged QTc interval (usually more than 500 msec), which can lead to Torsades de pointes and sudden cardiac death. It is a form of an inherited long QT syndrome (LQTS). The disease was first described in 1957 by Anton Jervell and Fred Lange-Nielsen in a study of 4 children born with congenital deafness that all suffered from syncope. There was a marked prolongation of the QT interval on electrocardiographic studies with no other identifiable cause for the patient’s fainting spells.[1]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

JLNS is a congenital disorder that is inherited in an autosomal recessive manner. Most cases are due to deletion mutations in the KCNQ1 (90%) and KCNE1 genes, which encode proteins essential in the potassium channels' functions in the heart and cochlea.[2]

Epidemiology

The prevalence of the disorder highly depends on the population studied but overall, it affects from 1 to 6 people per 1,000,000. Due to established genetic traits, Norway and Sweden have an unusually high prevalence at 1 in 200,000.[2] There have also been reports of an increased incidence in Turkey.[3]

Pathophysiology

The cardiac action potential comprises a depolarization, a plateau/refractory, and rapid repolarization phases. The repolarization phase is seen on the ECG as the QTc interval. It is associated with an increase in potassium permeability, which moves potassium out of the cardiac cell. This repolarizing potassium current, the delayed outward rectifier current, has a rapidly activating component and a slowly activating component.[4] Mutations in the KCNQ1 and KCNE1 genes encode the alpha and beta subunits of the slowly activating components resulting in a slower movement of potassium outside the cell, which prolongs the QTc interval.[2]

History and Physical

Classically, JLNS is suspected in a deaf child who experiences syncopal episodes that are often precipitated by emotion or exercise. Fifty percent of patients have a cardiac event by age three. Other pertinent clues are a history of iron deficiency anemia and elevated gastrin levels.[2] A physical exam is mostly unremarkable other than deafness.

Evaluation

Once JLNS is suspected in a child with congenital deafness and syncopal episodes, the next step is to evaluate the QTc interval to check if it is longer than 500 msec. Identifying the pathogenic variants in either the KCNQ1 or KCNE1 confirms the diagnosis. Testing for the genes can either be done as a single-gene test, a multigene panel, or comprehensive genomic testing.[2]

Once the diagnosis is established, the extent of the disease should be assessed. Evaluation should include a formal audiology evaluation, geneticist consultation, complete blood count to look for anemia, thorough family history.[2]

Treatment / Management

The first-line therapy in preventing syncope, cardiac arrest, and sudden death is a beta-blockade. Propranolol and nadolol have been shown to be superior to metoprolol in preventing cardiac events. The current consensus is that nadolol as the most preferred.[5] In patients with a history of cardiac arrest, an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) should be placed. Other indications for ICD placement is in patients who are deemed high risk. These include a QTc interval greater than 550 msec, syncope before age 5, and a male older than 20 years with the KCNQ1 pathogenic variant.[6](B2)

Despite beta-blocker therapy in symptomatic pediatric patients, Fruh et al. from Norway endorse the combined modality of atrial pacemaker and beta-blocker.[7]

Hearing loss is usually treated successfully with cochlear implantation.[8](B3)

Anesthesia for any surgical procedure has implications in a patient with JLNS. Any trigger to arrhythmia, including sympathetic overdrive, hypo- or hyperthermia, hypovolemia, and hypercarbia, should be carefully avoided. High airway pressure should be avoided. Beta-blockers should be readily available along with equipment for immediate transcutaneous or transvenous pacing and defibrillation.

Differential Diagnosis

The other most common etiologies of long QT syndromes, which must be considered in the differential diagnosis, include the following:

- Romano-Ward syndrome (RWS) is an autosomal dominant syndrome characterized by a prolonged QTc interval in the absence of congenital deafness. The mechanism of action is similar to JLNS in that it also affects the sodium and potassium channels. The diagnosis of RWS is made based on a prolonged QT interval on ECG, clinical presentation, and family history. The most common genes associated with the syndrome are KCNQ1, KCNH2, and SCN5A. Only the KCNQ1 and KCNE1 genes have been linked to both JLNS and RWS.[9]

- Timothy syndrome is a rare autosomal disease characterized by:

- Cardiac abnormal rhythm including QTc prolongation, functional 2:1 AV block with bradycardia, tachyarrhythmias,

- Congenital heart defects (patent ductus arteriosus, patent foramen ovale, ventricular septal defect, tetralogy of Fallot, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy)

- Syndactyly,

- Developmental delays, autism spectrum disorders.

The diagnosis is made by clinical features and a defective CACNA1C gene, which encodes a calcium channel. The prognosis is dismal, with an average age of death in patients with this disease is 2.5 years.[10]

- Andersen Tawil syndrome is also a rare autosomal dominant disorder characterized by a triad of :

- Episodic flaccid paralysis,

- Prolonged QT interval/ventricular arrhythmias

- Physical abnormalities including low-set ears, hypertelorism (widely spaced eyes), small jaw, fifth-digit clinodactyly, syndactyly, short stature, and scoliosis.

The diagnosis is made by clinical characteristics and a pathogenic variant in the KCNJ2 gene.[11]

- Acquired causes of QTc interval prolongation are most often caused by specific drugs (antiarrhythmics, pro-motility, antimicrobial, and antipsychotics), hypokalemia, hypocalcemia and hypomagnesemia.

- Myocardial problems such as myopathies and ischemia and central nervous system injuries.[12]

Prognosis

More than half of untreated children with JLNS die before age 15.[2] Prognosis is highly dependent on which gene is mutated, gender, and baseline QTc. Mutations in the KCNE1 genes are associated with a more benign course. Lower risk individuals include females with a QTc less than 550 msec. Goldenberg et al., in their review of high-risk Long QT syndrome patients, showed that Implanted cardioverter-defibrillator protects against JNLS related mortality.[13] Starting beta-blocker therapy early in the disease state is associated with fewer cardiac events and improved mortality.[6]

Complications

Complications of untreated disease can lead to syncope, cardiac arrest, and sudden death.[2]

Deterrence and Patient Education

Jervell and Lange Nielsen Syndrome (JLNS) is a rare inherited disorder affecting the heart's electrical system and ears. Symptoms are often seen at an early age and include episodes of fainting spells associated with intense emotion and exercise and also hearing loss. The treatment of JLNS is aimed at fixing the hearing loss and preventing further attacks of unconsciousness called syncope or possibly cardiac arrest. The hearing loss is corrected by a medical device called a cochlear implant, which stimulates the brain's nerve that recognizes sounds. A medication class called beta-blockers treat the cardiac abnormalities. These medications decrease the electrical stimulation to the heart and help prevent further abnormal rhythms that can lead to unconsciousness. If the medications fail or if an individual falls into a high-risk category, a device called an implantable automatic cardioverter-defibrillator is usually placed. This device detects an abnormal rhythm and sends an electrical shock to the heart, preventing syncope. Regular follow-up with the patient's pediatrician/primary care doctor and cardiologist is essential in preventing complications. Genetic evaluation of the patient and the family members is recommended.

Pearls and Other Issues

Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome (JLNS) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder that classically presents in a deaf child with recurrent syncopal episodes. It is a form of a prolonged QT syndrome that is characterized by a QTc greater than 500 msec and bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. Cardiovascular complications are managed with beta-blockade (preferably with nadolol) and ICD evaluation. Hearing loss is treated with cochlear implantation. Differential diagnoses of JLNS include Romano-Ward syndrome, Timothy syndrome, Andersen Tawil syndrome, and acquired causes such as electrolyte abnormalities and drugs.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

JLNS is a disorder that is usually caught early in life and requires an interprofessional approach in treating the patient. (Level V) This is generally started with the pediatrician who initially diagnoses the disease and coordinates the care between the interprofessional team, including:

- Electrophysiology in determining appropriate medical therapy, ICD appropriateness, and activity restrictions

- Audiology to assess the extent of hearing loss

- Ear, nose, and throat (ENT) physician for cochlear implantation

- Geneticist to determine appropriate molecular genetic testing and evaluating family at risk

As morbidity and mortality are high in patients with this disease, regular assessment of patient's cardiovascular needs will be necessary. This comprises beta-blocker dose adjustments and ICD placement evaluation. Once an ICD is placed, periodic evaluation of inappropriate shocks and lead complications is indicated.[2]

Media

References

JERVELL A, LANGE-NIELSEN F. Congenital deaf-mutism, functional heart disease with prolongation of the Q-T interval and sudden death. American heart journal. 1957 Jul:54(1):59-68 [PubMed PMID: 13435203]

Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Tranebjærg L, Samson RA, Green GE. Jervell and Lange-Nielsen Syndrome. GeneReviews(®). 1993:(): [PubMed PMID: 20301579]

Uysal F, Turkgenc B, Toksoy G, Bostan OM, Evke E, Uyguner O, Yakicier C, Kayserili H, Cil E, Temel SG. "Homozygous, and compound heterozygous mutation in 3 Turkish family with Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome: case reports". BMC medical genetics. 2017 Oct 16:18(1):114. doi: 10.1186/s12881-017-0474-8. Epub 2017 Oct 16 [PubMed PMID: 29037160]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShih HT. Anatomy of the action potential in the heart. Texas Heart Institute journal. 1994:21(1):30-41 [PubMed PMID: 7514060]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAckerman MJ, Priori SG, Dubin AM, Kowey P, Linker NJ, Slotwiner D, Triedman J, Van Hare GF, Gold MR. Beta-blocker therapy for long QT syndrome and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia: Are all beta-blockers equivalent? Heart rhythm. 2017 Jan:14(1):e41-e44. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.09.012. Epub 2016 Sep 19 [PubMed PMID: 27659101]

Schwartz PJ, Spazzolini C, Crotti L, Bathen J, Amlie JP, Timothy K, Shkolnikova M, Berul CI, Bitner-Glindzicz M, Toivonen L, Horie M, Schulze-Bahr E, Denjoy I. The Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome: natural history, molecular basis, and clinical outcome. Circulation. 2006 Feb 14:113(6):783-90 [PubMed PMID: 16461811]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceFrüh A, Siem G, Holmström H, Døhlen G, Haugaa KH. The Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome; atrial pacing combined with ß-blocker therapy, a favorable approach in young high-risk patients with long QT syndrome? Heart rhythm. 2016 Nov:13(11):2186-2192. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2016.07.020. Epub 2016 Jul 20 [PubMed PMID: 27451284]

Green JD, Schuh MJ, Maddern BR, Haymond J, Helffrich RA. Cochlear implantation in Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. The Annals of otology, rhinology & laryngology. Supplement. 2000 Dec:185():27-8 [PubMed PMID: 11140992]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAdam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Groffen AJ, Bikker H, Christiaans I. Long QT Syndrome Overview. GeneReviews(®). 1993:(): [PubMed PMID: 20301308]

Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Bean LJH, Gripp KW, Amemiya A, Napolitano C, Timothy KW, Bloise R, Priori SG. CACNA1C-Related Disorders. GeneReviews(®). 1993:(): [PubMed PMID: 20301577]

Nguyen HL, Pieper GH, Wilders R. Andersen-Tawil syndrome: clinical and molecular aspects. International journal of cardiology. 2013 Dec 5:170(1):1-16 [PubMed PMID: 24383070]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKallergis EM, Goudis CA, Simantirakis EN, Kochiadakis GE, Vardas PE. Mechanisms, risk factors, and management of acquired long QT syndrome: a comprehensive review. TheScientificWorldJournal. 2012:2012():212178. doi: 10.1100/2012/212178. Epub 2012 Apr 19 [PubMed PMID: 22593664]

Goldenberg I, Moss AJ, Zareba W, McNitt S, Robinson JL, Qi M, Towbin JA, Ackerman MJ, Murphy L. Clinical course and risk stratification of patients affected with the Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome. Journal of cardiovascular electrophysiology. 2006 Nov:17(11):1161-8 [PubMed PMID: 16911578]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence