Introduction

Vaginal delivery is safest for the fetus and the mother when the newborn is full-term at the gestational age of 37 to 42 weeks. Vaginal delivery is preferred considering the morbidity and the mortality associated with operative cesarean births has increased over time.[1] Approximately 80% of all singleton vaginal deliveries are at full-term via spontaneous labor, whereas 11% are preterm, and 10% are post-term.[2] Of note, with the advent of operative delivery modalities and surgical delivery modalities, the number of patients who reach spontaneous labor has decreased over time, and the induction of labor has increased.[3]

The labor leading to the delivery is divided into 3 stages, and each stage requires specific management. Complications arise during each of the three stages, which can lead to the conversion of the anticipated vaginal delivery to operative cesarean delivery. According to the latest published data, in the USA, in 2017, there were 3,855,500 births, and 68% (2,621,010) of those were vaginal deliveries. The preterm birth rate was 9.9%, and the population’s birth rate was 11.8 per 1000.[4]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

The labor leading to delivery of a full-term pregnancy is divided into three stages. The management of each stage varies, and exam findings during each of the stages can help identify short-term and long-term complications for the anticipated vaginal delivery such as fetal distress and hypoxemia, cord prolapse, placental abruption, uterine rupture, permanent disability, and maternal and/or fetal death.[5]

The first stage of labor is the longest stage of labor; it is the result of progressive and rhythmic uterine contraction which causes the cervix to dilate. The first stage of labor is divided into two sub-stages. The first sub-stage is known as the latent phase, which can last for several hours and starts from the cervical size of 0 cm to dilation of the cervix to 6 cm. The second sub-stage is known as the active phase, which includes the time from the end of the latent phase to the complete dilation of the cervix. This phase is rapid; in nulliparous women, the cervix dilates at an approximate rate of 1.00 cm/hour. It dilates slightly faster at a rate of 1.2 cm/hour in multiparous women.[6]

The second stage of labor includes the time from complete cervical dilation, which is the end of the first stage to delivery of the fetus. Duration of this phase is variable and can last from minutes to hours; however, the maximum amount of time that a woman can be in this phase of labor depends on the parity of the patient and whether the patient has an epidural catheter placed for anesthesia.[7]

During this stage, three clinical parameters are important to be aware of, which include fetal presentation, fetal station, and fetal position. The fetal presentation is dictated by which fetal body part first passes through the birth canal; most commonly, this is the occiput or the vertex of the head. The fetal station is determined by the relationship between the fetal head and maternal ischial spines; the station is defined from a range of -5 to +5, and 0 indicates that the fetal head is level with the maternal ischial spines. The fetal position is defined as the position of the top of the fetus’ head in comparison to the plane of the maternal ischial spines when it is born. The vertex, which is the top of the fetus’ head, normal rotates in either direction during the internal rotation portion of the cardinal movements during childbirth.[3]

There are six cardinal movements of childbirth, all of which occur during the second stage of labor. The first of these movements is engagement, which occurs when the head of the fetus enters the lower pelvis. Then, there is flexion of the head, which enables the occiput of the head of the fetus to be in a presentation position. This flexion is then followed by descent when the fetus descends through the birth canal through the pelvis. Once the descent is complete, there is internal rotation, which enables the vertex of the fetal head to rotate away from the ischial spines located laterally. Then, there is an extension of the head, which allows the fetal head to pass the maternal pubic symphysis, and finally, there is external rotation of the head, which allows the anterior shoulder to be delivered. The second stage of labor ends once the fetus is delivered.[3]

The final stage of labor includes the time after the child is born to the delivery of the placenta. The duration of this phase is approximately 30 minutes;[8] during this time, as the uterus contracts, the placenta separates from the endometrium. This process begins at the lower pole of the placenta, and progress is along with the adjacent sites of placental attachment. The continual uterine contraction causes a wave-like separation in the upward direction, which causes the most superior portion of the placenta to detach last. Signs of placental detachment include a sudden gush of blood, lengthening of the umbilical cord, and cephalad movement of the uterine fundus, which becomes firm and globular once the placenta detaches. The third stage of labor concludes once the placenta completely separates and is delivered.[9]

Indications

For full-term pregnancies, vaginal delivery is indicated when spontaneous labor occurs or if amniotic and chorionic membranes rupture. In addition, for complicated gestations or for post-term pregnancies, induction of labor is indicated, which is also an indication for vaginal delivery.

For women in spontaneous labor, the consensus in the review of the literature reveals that if the woman has regular contractions that require her focus and attention combined with either sufficient effacement (greater than or equal to 80%) and/or 4-5 cm of cervical dilation, the woman is in spontaneous labor and should be admitted to the hospital for a normal spontaneous vaginal delivery. It is important to note that woman near labor can feel regular contractions, but can present without cervical effacement or dilation and can be discharged with a follow up after routine monitoring of the fetus’ heart rate and monitoring contractions with a tocodynamometer. Subsequently, some women with cervical dilation or effacement without sufficient spontaneous contractions can be admitted for augmentation and induction of labor using oxytocin.[1]

The rupture of membranes is another indication of vaginal delivery. This may be indicated by a sudden gush of watery-fluid reported by the mother, which may be associated with a uterine contraction. Not all vaginal fluid is amniotic fluid, and this can be confirmed by multiple modalities, such as the pH of the fluid, microscopic visualization for the amniotic fluid for ferning, fetal fibronectin assays, and amniotic fluid nitrazine tests. Rupture of membranes at term gestation is an indication for vaginal delivery.[10] Management of a patient's preterm premature rupture of membranes is dependent on the gestation of pregnancy, among other maternofetal characteristics.

Certain conditions necessitate the induction of labor as timely delivery of pregnancy is important to peripartum outcomes of both the mother and fetus. Conditions such as post-term pregnancy (defined as gestation that is greater than 42 weeks and 0 days),[11] pre-labor rupture of membranes, gestational hypertensive disorders (preeclampsia, eclampsia), HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count) syndrome, fetal demise, fetal growth restriction, chorioamnionitis, oligohydramnios, placental abruption, intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, among other conditions are all indications for labor and vaginal delivery.[3]

Contraindications

Vaginal delivery is the preferred method for childbirth; however, there are certain conditions when vaginal delivery is contraindicated. Certain conditions require immediate conversion of vaginal delivery to an emergent cesarean section for childbirth, while some conditions can spontaneously resolve, and trial of vaginal delivery can be attempted.

Conditions that require prompt cesarean section and are contraindications to vaginal delivery can be categorized by the system; certain presentations such as footling breech, frank breech, complete breech, and cord prolapse are indications for emergent conversion to cesarean section.[12] Pathologies associated with malposition of the fetus, such as face presentation with mentum (chin in the direction of the maternal sacrum) posterior, transverse lie or shoulder presentation, and occiput posterior, should be converted to an abdominal delivery.[13] Twin gestations when presenting twin is in a breech position, conjoined twins and mono-amniotic twins are contraindications for vaginal delivery.[14] Abnormal placenta positions such as placenta previa, known placenta accreta, or history of uterine rupture are conditions that are contraindications for vaginal delivery.[15] Infection such as active genital herpes outbreak is also an absolute contraindication for vaginal delivery.[16] In the USA, higher-order births are also contraindications for vaginal delivery.

Relative contraindications also exist for vaginal delivery. There are certain conditions where vaginal delivery can be tried. During labor, if the fetus presents in a brow situation, this may spontaneously convert to face or vertex presentations, which can then progress to vaginal delivery. Nonreassuring fetal heart rate patterns, such as Category II and Category III fetal heart rate tracings that can signal fetal hypoxia or acidosis, may represent cord compression and entrapment can indicate avoidance of vaginal delivery.[17] Trial of Labor after Caesarean section (TOLAC) can also be attempted but is contraindicated when there is a history of multiple cesarean sections, history of placenta previa, and evidence of cephalopelvic disproportion as indicated by macrosomia.[18] Fetal weight greater than 5000 grams in a mother with diabetes or fetal weight greater than 4500 grams in a mother without diabetes are relative contraindications for vaginal delivery.[19]

Equipment

Ensuring proper equipment is essential to a successful vaginal delivery and to minimize fetal and maternal morbidity and mortality. Appropriate equipment is necessary to anticipate and appropriately manage improbable but realistic complications of low-risk vaginal deliveries, as 20% to 25% of all perinatal morbidity and mortality occurs in pregnancies devoid of risk factors for adverse outcomes.[20]

Appropriate preparation includes a warm and clean room with adequate lighting and supplemental light source, a delivery bed with clean linen whose height can be adjusted, a plastic sheet to place under the mother, chlorhexidine, and wipes. There should be equipment for barrier protection such as gloves and masks. Sterile equipment includes appropriate sterile gloves, sterile instruments such as scissors, needle holders, artery forceps for cord clamping, dissecting forceps, sponge forceps, sterile blade, and cord ties.[21]

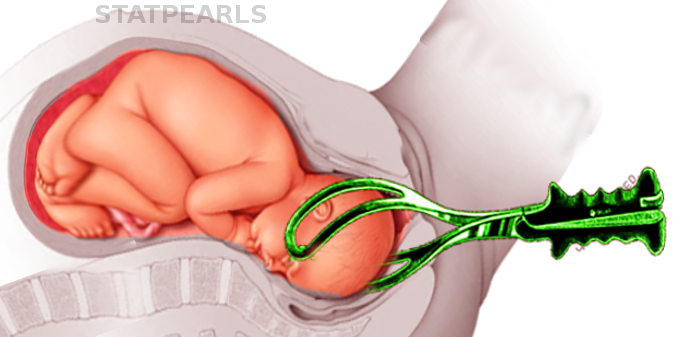

The list of equipment needed also includes a tocodynamometer to monitor uterine contractions using an external monitor or an intrauterine pressure catheter and fetal heart rate monitor with either external heart rate monitor or an internal fetal heart rate monitor (scalp electrode). If the delivery needs assistance, either forceps or vacuum can be kept bedside to assist in vaginal delivery.[22]

Analgesia can be kept bedside, but is not absolutely needed, as the use of oral or epidural analgesia is based on maternal preference.

Personnel

For a normally anticipated vaginal delivery, a physician or a midwife with the aide of a nurse can appropriately and safely perform the procedure. Additional personnel are optional, however additional support and coaching from a formally trained doula, family member, and/or partner can enhance the experience for the mother and results in a decreased need for analgesia.[23] In addition, a pediatrician and an anesthesiologist should be available and on-call for any complications related to vaginal delivery.

Preparation

As with any procedure, appropriate preparation and positioning of the patient are key to maximizing the success of the procedure while simultaneously minimizing morbidity and mortality. There are many factors to consider in preparing a patient for a vaginal delivery and the position of the patient changes based on the progression of labor through its various stages.

Patients should be adequately hydrated, as hypovolemia during labor can cause fetal heart tracing abnormalities.[24] Routine administration of antacids, routine enemas, and perineal shaving is not indicated.[25][26][27][26][25] Systemic antibiotics are indicated for a known positive Group B streptococcus (GBS) culture or unknown maternal GBS status.[28] There is no evidence in the literature supporting intrapartum chlorhexidine to prevent maternal or neonatal infections during vaginal delivery; conversely, this can lead to vaginal irritation and discomfort.[29] However, some institutions and providers routinely use povidone-iodine solutions, especially if there is intrapartum defecation during labor and delivery.

Once the patient is prepared for the delivery, it is important to ensure proper positioning for the vaginal delivery. For the first stage of labor, the patient should be connected to monitors to assess fetal and maternal vital signs, as well as maternal uterine contractions. Progression of labor can be assessed by regular pelvic exams to assess for cervical effacement and dilation; this examination can be done every three or four hours, or as needed. A Foley urinary catheter can be placed; however, it is not necessary. Current literature suggests that bladder distension does not affect labor progress.[30] During the first stage of labor, mothers are encouraged to ambulate and move around on the bed until a comfortable position is reached. Walking during the first stage of labor has no effect on the progress of and does not cause inhibition of normal labor.[31]

For the second stage of labor, it is important to chart fetal station and cervical dilation at each examination. Pushing with contractions should begin and be encouraged once the cervix has completely dilated. At the time, the birthing bed should be detached with the physician by the patient’s vagina. The patient is encouraged to be in a position that is most comfortable for her while pushing, but it is generally a lying position where the patient is supine lithotomy position.

Once the fetus is delivered, during the third stage of labor, optimally, the fetus is placed on the mother’s chest with the umbilical cord initially clamped then cut, while the mother continues to maintain the same position until the placenta is delivered. After the placenta is delivered and all equipment is cleared, the mother can lay supine and recumbent in a position she finds most comfortable.

Technique or Treatment

Once maximal cervical dilation is reached and the patient experiences regular contractions every two to three minutes, she should be encouraged to push. The best way to push is bearing down, and the patient can be coached by asking the patient to push for at least ten seconds and for at least two or three times per contraction.[32] The patient should be encouraged to push towards the baby’s head, and can also be encouraged by asking the patient to minimize yelling while maximizing pushing.

While the patient continues to push, warm compresses can be applied, and the perineum can be massaged digitally with lubricant to soften and stretch the perineum. In women without a history of vaginal birth, perineal massage reduced the incidence of perineal trauma and the need for episiotomies but did not reduce the incidence of perineal trauma of any degree.[33] The second stage of labor can continue as long as needed as long as fetal heart rate tracing is normal, and progress is achieved, which can be quantified by progression in the fetal station. Once the fetus reaches +5 fetal station, which is crowning, the delivery of the fetus is imminent. At this time, the head of the fetus exerts dilatory pressure on the perineum, which leads to a tremendous urge for mothers to push, but appropriate steps of delivery should be followed in order to minimize perineal trauma.

Once the head crowns, a sterile towel or lap pad can be used to hold the fetal head; one hand should support the fetal head and maintain it in the flexion position while the other hand should be used to support the lower edge of the perineum by pinching it to avoid tearing or trauma.[34] During this time, the mother should be encouraged to stop pushing, and then use small contractions to enable the physician to control the pace of the fetal head delivery; precipitous delivery of the head can cause perineal trauma. Once the head is delivered, the mother should once again be asked to stop pushing, and the neck should be manually examined for the umbilical cord. If a nuchal cord is detected, it should be reduced[35], and then the delivery of the rest of the fetus should continue.

Routine oropharyngeal care through suctioning is no longer supported by evidence as gently wiping mucus from the child’s face and nose is found to be equivalent.[36] Once the head is delivered, the next step is for delivery of the shoulders. With the next contraction, and using gentle downward traction towards the mother’s sacrum, the anterior shoulder is delivered as each side of the head is held. This maneuver allows the anterior shoulder to pass under the maternal pubic symphysis. While continuing to hold each side of the head, the posterior shoulder is delivered by applying gentle upward traction. It is important to apply the least amount of traction during the delivery of fetal shoulders to minimize the risk of traction-induced perineal injury and fetal brachial plexus injuries.[37] After the shoulders are delivered, care must be maintained as the rest of the delivery is spontaneous and requires minimal maternal effort, but it is important to guide the newborn child’s body as it passes the birth canal. Once the child is delivered, the umbilical cord should be clamped after a delay. In full-term vaginal deliveries, evidence supports that delayed cord clamping, which is defined as clamping of the cord after 30 seconds, prevents anemia in infants. The umbilical cord should be clamped using two clamps that are approximately three to four centimeters apart. The partner of the mother or the accompanying family member should be afforded the opportunity to cut the umbilical cord between the two clamps. Once the cord is cut, the newborn should be cleaned, and one-minute and five-minute APGAR scores should be evaluated. If the APGAR scores are within normal limits, the infant should immediately be transferred to the mother and placed on her bare chest. Early Skin-to-skin contact between the newborn infant and mother serves a multitude of functions. It has been shown to increase mother-infant bond and attachment, improve breastfeeding outcomes, and minimize infant head loss.[38][39]

The third stage of labor is defined as the time from the delivery of the fetus until the delivery of the placenta. Active management at this time of delivery can reduce the risk of severe postpartum hemorrhage and the need for blood transfusion. The active management of the third stage begins before the delivery of the placenta and includes uterotonic agent administration, application of gentle traction to umbilical cord after clamping it, and uterine massage.[40] The preferred uterotonic agent is oxytocin, which is administered immediately after the delivery of the fetus. Signs of placental separation from the uterus, such as a gush of blood, should be observed as the uterus contracts. Cord traction facilitates the separation of the placenta and enables its delivery. One method of cord traction application is known as the Brandt-Andrews maneuver, in which one hand secures the uterine fundus on the abdomen to prevent uterine inversion while the other hand exerts sustained downward gentle traction of the clamp on the umbilical cord. This maneuver leads to a reduction in the need for manual placental removal; in addition, there is a statistically significant reduction in the duration of the third stage of labor, blood loss, and incidence of postpartum hemorrhage. Once the placenta is delivered, it should be thoroughly inspected on the outside and by inverting it to check for missing pieces, because retained products of conception are a known risk factor for postpartum hemorrhage.

After the placenta is delivered, the vaginal canal should be inspected for any lacerations, and if lacerations are detected, they should be repaired.

Complications

There are numerous complications associated with vaginal delivery; these complications vary by stages of labor and are dependent on numerous factors. In general, complications can be generalized into the following categories: failure to progress, abnormal fetal heart rate tracing, intrapartum hemorrhage, and post-partum hemorrhage.

Failure to progress can happen in either the first stage or the second stage. Failure to progress in the first stage of labor can be either protraction of active phase of labor, which is defined as cervical dilation rate less than one to two centimeters per hour in women who’s cervix is at least six centimeters dilated.[41] The arrest of the first stage of labor is defined as no change in cervical dilation for more than four hours in a woman with adequate uterine contraction strength (defined as 200 Montevideo units or greater) or no change in cervical dilation in a woman for more than six hours with inadequate contraction strength. Protracted labor can be managed by augmenting labor with oxytocin, which is a uterotonic agent.[42] Women with arrested labor are managed by conversion of vaginal delivery to a cesarean section mode of delivery.[43]

Failure to progress during the second stage of labor is diagnosed when there is minimal descent of the fetus in nulliparous women who have pushed for a minimum of three hours and multiparous women who have pushed for a minimum of two hours; women with epidural anesthesia are allowed slightly longer durations for pushing.[44] Failure to progress during the second stage of labor due to inadequate contractions or minimal descent of the fetus can be managed by the administration of oxytocin to augment labor after 60-90 minutes of pushing. If this does not help, an operative vaginal delivery using a vacuum or forceps or a cesarean section should be considered.

Failure to progress can also be due to abnormal passage of descent for the fetus, which is directly related to cephalopelvic disproportion (CPD). CPD can be related to fetal malposition or macrosomia and is a subjective diagnosis which requires conversion of the delivery to a cesarean section. CPD is most commonly observed during the second stage of labor.[45]

During a vaginal delivery, the fetal heart rate must be monitored, and decelerations during labor, whether early decelerations or late decelerations, can indicate head compression of the fetus, cord compression of the fetus, hypoxemia, and even anemia of the fetus. If an abnormal fetal heart rate persists, resolution can be attempted by removing labor augmenting agents such as oxytocin or repositioning the mother on the left lateral side.[46] If these maneuvers do not lead to the resolution of the abnormal fetal heart rate, an emergent cesarean section is indicated.

Vaginal delivery can be complicated by intrapartum hemorrhage. During a normal vaginal delivery, some blood from the effacement of the cervix or minor trauma of the vaginal canal can mix with amniotic fluid and can present as a serosanguineous appearance. However, the presence of frank blood is abnormal and can either be due to placental abruption, uterine rupture, placenta accrete, undiagnosed placenta previa, or vasa previa. These conditions are true obstetric emergencies and require an emergent cesarean section.[47]

Finally, vaginal deliveries can be complicated by postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). PPH can be due to atony of the uterus, trauma to the birth canal, retained products of conception or due to a coagulopathy; uterine atony is the most common cause of PPH.[7]

Clinical Significance

Proper preparation, monitoring, and technique during vaginal delivery are important to minimize morbidity and mortality to both the mother and the fetus. According to the latest data on births in the United States,[4] The incidence of cesarean delivery increased from 2016 to 2017, which is the first increase since 2017. While cesarean section deliveries are absolutely necessary for certain peripartum conditions, cesarean section deliveries have been shown to increase the long-term risk of small bowel obstruction in women.[48]

Additionally, cesarean sections correlate with an increased risk of uterine rupture, abnormal placentation for future pregnancies, ectopic pregnancies, preterm births, and stillbirth. Evidence suggests cesarean section deliveries lead to differing and altered physiology in neonates due to exposure to differing hormonal, physical, microbiological, and medical exposures, which can affect short-term and long-term development. Short-term risks to babies include alteration in the immune system, increased likelihood in developments of allergies, asthma, and reduced intestinal microbiome, while long-term risks include the development of obesity and risks associated with obesity.

Conversely, advantages of a successful vaginal delivery are numerous to both the baby and the mother. With a vaginal delivery, there is a higher chance of being able to breastfeed successfully shortly after delivery, decreased hospital stay after childbirth, rapid recovery physically and psychologically, and increased mother-child bond and attachment. For the baby, the benefits of vaginal delivery include improved hormonal and endocrinological functions such as blood sugar regulation, respiratory function, temperature regulation, and an increase in exploratory behaviors. Other benefits include better long-term growth, immunity, and development compared to children born as a result of a cesarean section.[49]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Vaginal delivery is a major and ubiquitous procedure that can be associated with serious morbidities and potential mortality to the mother and the neonate due to a number of intrapartum and postpartum complications related to the procedure. Maternal complications include, but are not limited to, placental abruption, uterine rupture, postpartum hemorrhage, endometritis, amniotic fluid embolism, and neonatal complications include sepsis, meningitis, shoulder dystocia, and brachial plexus injuries. Responsibilities of the healthcare team include minimizing these complications via proactive management of the patient during vaginal delivery.

While some women opt for home births, pregnant women are unable to confirm the rupture of membranes, check for cervical dilation or effacement, and the healthcare team's goal is to ensure safe progression through labor and to lead to the successful delivery of the baby. Nurses and midwives are needed to help the patient get ready and motivate her through labor, and even facilitate the delivery of the baby, physicians are responsible for monitoring the fetal and maternal well-being while being cognizant of possible complications and treating those.

A collaborative effort between the patient, her support system, the nurses, technicians, and physicians is required for successful vaginal delivery to minimize morbidity and mortality.

Media

References

Lagrew DC, Low LK, Brennan R, Corry MP, Edmonds JK, Gilpin BG, Frost J, Pinger W, Reisner DP, Jaffer S. National Partnership for Maternal Safety: Consensus Bundle on Safe Reduction of Primary Cesarean Births-Supporting Intended Vaginal Births. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Mar:131(3):503-513. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002471. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29470326]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceIams JD. Prediction and early detection of preterm labor. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2003 Feb:101(2):402-12 [PubMed PMID: 12576267]

. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 107: Induction of labor. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2009 Aug:114(2 Pt 1):386-397. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b48ef5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19623003]

Martin JA, Hamilton BE, Osterman MJK, Driscoll AK, Drake P. Births: Final Data for 2017. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2018 Nov:67(8):1-50 [PubMed PMID: 30707672]

Gregory KD, Jackson S, Korst L, Fridman M. Cesarean versus vaginal delivery: whose risks? Whose benefits? American journal of perinatology. 2012 Jan:29(1):7-18. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1285829. Epub 2011 Aug 10 [PubMed PMID: 21833896]

Zhang J, Troendle J, Mikolajczyk R, Sundaram R, Beaver J, Fraser W. The natural history of the normal first stage of labor. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2010 Apr:115(4):705-710. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181d55925. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20308828]

Le Ray C, Fraser W, Rozenberg P, Langer B, Subtil D, Goffinet F, PREMODA Study Group. Duration of passive and active phases of the second stage of labour and risk of severe postpartum haemorrhage in low-risk nulliparous women. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2011 Oct:158(2):167-72. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2011.04.035. Epub 2011 Jun 2 [PubMed PMID: 21640464]

Dombrowski MP, Bottoms SF, Saleh AA, Hurd WW, Romero R. Third stage of labor: analysis of duration and clinical practice. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1995 Apr:172(4 Pt 1):1279-84 [PubMed PMID: 7726270]

Herman A, Weinraub Z, Bukovsky I, Arieli S, Zabow P, Caspi E, Ron-El R. Dynamic ultrasonographic imaging of the third stage of labor: new perspectives into third-stage mechanisms. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 1993 May:168(5):1496-9 [PubMed PMID: 8498434]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmerican College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. Practice Bulletin No. 172: Premature Rupture of Membranes. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Oct:128(4):e165-77. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001712. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27661655]

. ACOG Committee Opinion No 579: Definition of term pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Nov:122(5):1139-1140. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437385.88715.4a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24150030]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHannah ME, Hannah WJ, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Saigal S, Willan AR. Planned caesarean section versus planned vaginal birth for breech presentation at term: a randomised multicentre trial. Term Breech Trial Collaborative Group. Lancet (London, England). 2000 Oct 21:356(9239):1375-83 [PubMed PMID: 11052579]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSharshiner R, Silver RM. Management of fetal malpresentation. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Jun:58(2):246-55. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000103. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25811125]

Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine. Practice Bulletin No. 169: Multifetal Gestations: Twin, Triplet, and Higher-Order Multifetal Pregnancies. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2016 Oct:128(4):e131-46. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001709. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27661652]

Chibber R, El-Saleh E, Al Fadhli R, Al Jassar W, Al Harmi J. Uterine rupture and subsequent pregnancy outcome--how safe is it? A 25-year study. The journal of maternal-fetal & neonatal medicine : the official journal of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, the Federation of Asia and Oceania Perinatal Societies, the International Society of Perinatal Obstetricians. 2010 May:23(5):421-4. doi: 10.3109/14767050903440489. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20230321]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceACOG Committee on Practice Bulletins. ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. No. 82 June 2007. Management of herpes in pregnancy. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2007 Jun:109(6):1489-98 [PubMed PMID: 17569194]

Liston R, Sawchuck D, Young D, Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecologists of Canada, British Columbia Perinatal Health Program. Fetal health surveillance: antepartum and intrapartum consensus guideline. Journal of obstetrics and gynaecology Canada : JOGC = Journal d'obstetrique et gynecologie du Canada : JOGC. 2007 Sep:29(9 Suppl 4):S3-56 [PubMed PMID: 17845745]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence. ACOG Practice bulletin no. 115: Vaginal birth after previous cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2010 Aug:116(2 Pt 1):450-463. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181eeb251. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20664418]

Baxley EG, Gobbo RW. Shoulder dystocia. American family physician. 2004 Apr 1:69(7):1707-14 [PubMed PMID: 15086043]

Zapata-Vázquez RE, Rodríguez-Carvajal LA, Sierra-Basto G, Alonzo-Vázquez FM, Echeverría-Eguíluz M. Discriminant function of perinatal risk that predicts early neonatal morbidity: its validity and reliability. Archives of medical research. 2003 May-Jun:34(3):214-21 [PubMed PMID: 14567402]

. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Postpartum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice. 2015:(): [PubMed PMID: 26561684]

Danilack VA, Nunes AP, Phipps MG. Unexpected complications of low-risk pregnancies in the United States. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Jun:212(6):809.e1-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.03.038. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26042957]

Sosa R, Kennell J, Klaus M, Robertson S, Urrutia J. The effect of a supportive companion on perinatal problems, length of labor, and mother-infant interaction. The New England journal of medicine. 1980 Sep 11:303(11):597-600 [PubMed PMID: 7402234]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence. Practice Guidelines for Obstetric Anesthesia: An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Obstetric Anesthesia and the Society for Obstetric Anesthesia and Perinatology. Anesthesiology. 2016 Feb:124(2):270-300. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000935. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26580836]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGyte GM, Richens Y. Routine prophylactic drugs in normal labour for reducing gastric aspiration and its effects. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006 Jul 19:2006(3):CD005298 [PubMed PMID: 16856089]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceReveiz L, Gaitán HG, Cuervo LG. Enemas during labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Jul 22:2013(7):CD000330. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000330.pub4. Epub 2013 Jul 22 [PubMed PMID: 23881649]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBasevi V, Lavender T. Routine perineal shaving on admission in labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Nov 14:2014(11):CD001236. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001236.pub2. Epub 2014 Nov 14 [PubMed PMID: 25398160]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBonet M, Ota E, Chibueze CE, Oladapo OT. Routine antibiotic prophylaxis after normal vaginal birth for reducing maternal infectious morbidity. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Nov 13:11(11):CD012137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012137.pub2. Epub 2017 Nov 13 [PubMed PMID: 29190037]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLumbiganon P, Thinkhamrop J, Thinkhamrop B, Tolosa JE. Vaginal chlorhexidine during labour for preventing maternal and neonatal infections (excluding Group B Streptococcal and HIV). The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2014 Sep 14:2014(9):CD004070. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004070.pub3. Epub 2014 Sep 14 [PubMed PMID: 25218725]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceKerr-Wilson RH, Parham GP, Orr JW Jr. The effect of a full bladder on labor. Obstetrics and gynecology. 1983 Sep:62(3):319-23 [PubMed PMID: 6877688]

Bloom SL, McIntire DD, Kelly MA, Beimer HL, Burpo RH, Garcia MA, Leveno KJ. Lack of effect of walking on labor and delivery. The New England journal of medicine. 1998 Jul 9:339(2):76-9 [PubMed PMID: 9654537]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceLemos A, Amorim MM, Dornelas de Andrade A, de Souza AI, Cabral Filho JE, Correia JB. Pushing/bearing down methods for the second stage of labour. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2017 Mar 26:3(3):CD009124. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009124.pub3. Epub 2017 Mar 26 [PubMed PMID: 28349526]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBeckmann MM, Stock OM. Antenatal perineal massage for reducing perineal trauma. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2013 Apr 30:2013(4):CD005123. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005123.pub3. Epub 2013 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 23633325]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFretheim A, Odgaard-Jensen J, Røttingen JA, Reinar LM, Vangen S, Tanbo T. The impact of an intervention programme employing a hands-on technique to reduce the incidence of anal sphincter tears: interrupted time-series reanalysis. BMJ open. 2013 Oct 22:3(10):e003355. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003355. Epub 2013 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 24154515]

Mercer JS, Skovgaard RL, Peareara-Eaves J, Bowman TA. Nuchal cord management and nurse-midwifery practice. Journal of midwifery & women's health. 2005 Sep-Oct:50(5):373-9 [PubMed PMID: 16154063]

Kelleher J, Bhat R, Salas AA, Addis D, Mills EC, Mallick H, Tripathi A, Pruitt EP, Roane C, McNair T, Owen J, Ambalavanan N, Carlo WA. Oronasopharyngeal suction versus wiping of the mouth and nose at birth: a randomised equivalency trial. Lancet (London, England). 2013 Jul 27:382(9889):326-30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60775-8. Epub 2013 Jun 3 [PubMed PMID: 23739521]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceDresang LT, Yonke N. Management of Spontaneous Vaginal Delivery. American family physician. 2015 Aug 1:92(3):202-8 [PubMed PMID: 26280140]

Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N, Dowswell T. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2012 May 16:5(5):CD003519. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub3. Epub 2012 May 16 [PubMed PMID: 22592691]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMoore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N. Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2007 Jul 18:(3):CD003519 [PubMed PMID: 17636727]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceGülmezoglu AM, Lumbiganon P, Landoulsi S, Widmer M, Abdel-Aleem H, Festin M, Carroli G, Qureshi Z, Souza JP, Bergel E, Piaggio G, Goudar SS, Yeh J, Armbruster D, Singata M, Pelaez-Crisologo C, Althabe F, Sekweyama P, Hofmeyr J, Stanton ME, Derman R, Elbourne D. Active management of the third stage of labour with and without controlled cord traction: a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet (London, England). 2012 May 5:379(9827):1721-7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60206-2. Epub 2012 Mar 6 [PubMed PMID: 22398174]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZhang J, Landy HJ, Ware Branch D, Burkman R, Haberman S, Gregory KD, Hatjis CG, Ramirez MM, Bailit JL, Gonzalez-Quintero VH, Hibbard JU, Hoffman MK, Kominiarek M, Learman LA, Van Veldhuisen P, Troendle J, Reddy UM, Consortium on Safe Labor. Contemporary patterns of spontaneous labor with normal neonatal outcomes. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2010 Dec:116(6):1281-1287. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fdef6e. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21099592]

Wei SQ, Luo ZC, Xu H, Fraser WD. The effect of early oxytocin augmentation in labor: a meta-analysis. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2009 Sep:114(3):641-649. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b11cb8. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19701046]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSpong CY, Berghella V, Wenstrom KD, Mercer BM, Saade GR. Preventing the first cesarean delivery: summary of a joint Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Workshop. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2012 Nov:120(5):1181-93 [PubMed PMID: 23090537]

. Obstetric care consensus no. 1: safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014 Mar:123(3):693-711. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000444441.04111.1d. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24553167]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSenécal J, Xiong X, Fraser WD, Pushing Early Or Pushing Late with Epidural study group. Effect of fetal position on second-stage duration and labor outcome. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2005 Apr:105(4):763-72 [PubMed PMID: 15802403]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 106: Intrapartum fetal heart rate monitoring: nomenclature, interpretation, and general management principles. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2009 Jul:114(1):192-202. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181aef106. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19546798]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceStranges E, Wier LM, Elixhauser A. Complicating Conditions of Vaginal Deliveries and Cesarean Sections, 2009. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs. 2006 Feb:(): [PubMed PMID: 22787679]

Abenhaim HA, Tulandi T, Wilchesky M, Platt R, Spence AR, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Suissa S. Effect of Cesarean Delivery on Long-term Risk of Small Bowel Obstruction. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2018 Feb:131(2):354-359. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002440. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29324607]

Buhimschi CS, Buhimschi IA. Advantages of vaginal delivery. Clinical obstetrics and gynecology. 2006 Mar:49(1):167-83 [PubMed PMID: 16456354]