Introduction

Ocular injury is common, with an estimated 24 million people in the United States suffering an eye injury.[1] Injuries to the eye vary in severity, from a small scratch to the cornea (corneal abrasion) to a split in the external structure (globe rupture). Globe rupture can occur in various parts of the eye; one example is a corneal laceration. In a review of 890 eye injuries in Iraq and Afghanistan from 2001 to 2011, 20.7% involved a corneal laceration.[2]

Corneal lacerations vary in size and shape, can be partial or full-thickness, and range from a simple linear pattern to a complex stellate formation. All lacerations require urgent repair to reduce the risk of infection, decrease tissue necrosis, and alleviate patient discomfort. The typical recommendation for a repair is within 24 hours.[3]

The repair of a corneal laceration often requires suturing; however, tissue adhesives or contact lenses can close lacerations less than 2 mm.[4]

The goal of any repair is a watertight closure, restoration of normal anatomy, and limiting the amount of post-operative corneal scarring and astigmatism.[5][6]

Anatomy and Physiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Anatomy and Physiology

A normal human cornea is transparent and avascular. It provides structural support to the eye and acts as a barrier to infections. The average adult cornea is 12 mm horizontally by 11 mm vertically and 0.5 mm in thickness.

There are five distinct layers of the cornea starting from the outer surface: epithelium, Bowman membrane, stroma, Descemet membrane, and endothelium. In 2013, a 6th layer was reported, called Dua’s layer, situated between the stroma and Descemet membrane. About 80 to 85% of the cornea is the stroma which consists of Type I and V collagen fibers arranged in specific parallel patterns to maintain transparency. The endothelial layer is monocellular and responsible for the optical clarity of the cornea by keeping it dehydrated through a sodium-potassium pump.[7]

The corneal layers have different responses when injured. Injury to the epithelial layer leads to the destruction of the cells and a subsequent defect in the layer. This defect will heal by migrating epithelial cells created at the limbus. About an hour after the injury, the epithelial wound healing starts.[8] Until the defect has healed, the cornea is at significant risk of infection. If the depth of the injury did not violate the Bowman membrane, the cornea heals without scarring.

An injury to the stroma heals with fibrotic deposition, which seals a wound but interferes with normal function. Excess fibrotic tissue repair causes increased scarring and contracture, limiting the optical clarity.

Endothelial cells do not regenerate, and therefore when injured, the cornea may become edematous and cloudy due to the loss of the sodium-potassium pump function of the cells.

The cornea is a highly innervated and sensitive tissue, which receives sensation from the nasociliary branch of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve.[9] Due to the dense innervation, a patient can feel extreme pain from a corneal injury.

Indications

A diagnosis of corneal laceration by slit-lamp examination is an indication for repair. Signs and symptoms of a corneal laceration after trauma are decreased vision, ocular pain, a positive Seidel test, irregular pupil such as a peaked or teardrop pupil, intraocular foreign body, and prolapse of intraocular contents. If a corneal laceration is suspected, but the view on examination is limited due to an uncooperative patient or eyelid edema, the patient should go to the operating for an exam under anesthesia and globe exploration. A corneal laceration repair should occur urgently to reduce the risks of infection, tissue necrosis, peripheral anterior synechiae formation and alleviate patient discomfort. No specific time for repair is published in the literature, but the standard preferred practice is within 24 hours.

Contraindications

The patient must be hemodynamically stable before the repair. In the setting of polytrauma, the risk of general anesthesia may make a corneal laceration repair unsafe.[10]

Equipment

- Microscope or surgical loupes

- Surgical preparation kit (sponges, 5% povidone-iodine)

- Surgical eye drapes

- Suture: 10-0 nylon (if limbus or scleral involved: 9-0 and 8-0) ** Prime reverse cutting or spatulated needle **

- Eyelid speculum (Jaffe or Schott prevent pressure on the globe) **Eyelid sutures can be an alternative to the speculum **

- Needle holders

- 0.12 forceps (+/- Colibri Forceps)

- Surgical tying forceps

- Tenotomy and fine scissors

- Surgical blade (1.0 to 1.2 mm)

- Ophthalmic viscoelastic

- Balanced salt solution

- 3 mL syringe

- 27 or 30 gauge cannula

- Eye spears

- Cyclodialysis spatula (Used to displace iris from the corneal wound)

- Fluorescein strip

- Cyanoacrylate glue

- Bandage contact lens

- Irradiated corneal tissue or pericardium allograft (Needed if tissue is missing from trauma)

- Rigid eye shield

- Eye pads

- Post-operative antibiotics (intracameral, subconjunctival, or topical)

| Suture Size | Part of the Eye |

| 10-0 | Cornea |

| 9-0 | Limbus |

| 8-0 | Sclera |

The standard suture for a corneal laceration repair is 10-0 nylon with a fine spatulated needle. If a surgical needle has a high radius of curvature, it will lead to long passes, versus a smaller radius of curvature will lead to shorter passes.[3]

Personnel

- Ophthalmologist (surgeon)

- Surgical technician

- Operating room nurse

- Anesthesiologist/certified registered nurse anesthetist

Preparation

While the patient waits for a repair, cover the injured eye with a rigid eye shield.[11] Control pain and nausea with analgesics and antiemetics. Tell the patient to refrain from eating or drinking to be ready for surgery. Acquiring computed tomography(CT) of the face before the repair can identify foreign bodies, and is often the standard of care for ocular trauma at several institutions. Administer tetanus prophylaxis to the patient and start antibiotics early to prevent infection.[12][13]

Perform a basic eye exam cautiously to avoid worsening the injury or causing distress to the patient.[14] The exam can be challenging, but at minimum, perform a vision test with a Snellen chart or near vision card, pupil check, and a penlight or slit-lamp evaluation. Do not perform intraocular pressure if a full-thickness laceration is present or suspected. If unsure if the laceration is full-thickness, perform a Seidel test to confirm it.[15]

Before a corneal laceration repair, place a drop 5% povidone-iodine ophthalmic solution on the ocular surface as this is the most effective solution to reduce bacteria.[16] When performing the surgical preparation, ensure no pressure is applied to the eye to avoid protrusion of intraocular contents.

Technique or Treatment

The uniqueness of corneal lacerations for each patient leads to many ways to repair them. Each case is a puzzle, which the surgeon must complete. Some surgeons find joy in this, while others find it distressful. Despite your perspective and approach, the goal is to create a watertight closure by sealing the cornea without incorporating the intraocular contents, restoring the integrity of the globe, and preventing further damage to the cornea or other parts of the eye.[5] Following basic corneal suturing technique helps avoid excess postoperative corneal scarring and high residual astigmatism.

Anesthesia: Anesthesia management for corneal laceration repair varies from topical to general.[17] For a small laceration in the clinic, topical anesthesia or a peribulbar block may suffice. General anesthesia is ideal if the laceration is complex or tissue is protruding. General anesthesia is the preferred practice as it allows for a controlled repair and alleviates any patient anxiety or pain. A smooth induction is necessary for a full-thickness corneal laceration to prevent coughing, straining, or movement, which could cause prolapse of intraocular contents.[18]

Suspected corneal laceration: If unable to confirm a corneal laceration in the emergency room or clinic, transport the patient to the operating room for an exam under anesthesia and possible surgical repair.

Partial-thickness corneal laceration: Carefully debride partial-thickness lacerations. After debridement, perform a Seidel test to ensure that the laceration is still partial thickness. If the Seidel test is positive, it is a full-thickness laceration and follows the procedures below. If negative, use a contact lens or fibrin glue to help it heal and treat similar to a corneal abrasion.

Culture/Debride Laceration: Culture the wound carefully to avoid prolapsing intraocular tissue or pressure on the globe. The culture results can be beneficial if a patient develops an infection. Only the surgeon performing the repair should debride the tissue because improper debridement can further damage the eye. Excise necrotic tissue and reposit the remaining tissue into the eye. Remove any visible foreign bodies or debris.

Full-thickness corneal laceration less than 2 mm: Use cyanoacrylate or fibrin glue, amniotic membrane, or bandage contact lenses. However, if a watertight closure cannot be completed, suturing is required.[19][20][21] These techniques can often be completed in the clinic if the patient is cooperative. Many surgeons start with sutures for closure despite the size of the laceration. Sometimes it can be challenging to determine the size of the laceration on the bedside exam and is easier to evaluate in the operating room.

Full-thickness corneal laceration greater than 2 mm: This size of laceration usually requires sutures and should be repaired in the operating room.

Evaluate the laceration and plan before passing a suture. Drawing out the repair organizes the surgical approach. Once a plan is in place, start suturing. The needle should enter the cornea perpendicular to the tissue when passing a suture. One method is to hold one side of the corneal wound at a 45-degree angle and enter the tissue at 45 degrees. Rotate the wrist following the needle curvature and come out the other side of the wound perpendicular to the tissue. Tie the suture with a slip knot, 2-1-1, or 3-1-1, and then cut the loose ends. The smaller the knot, the easier it is to bury.

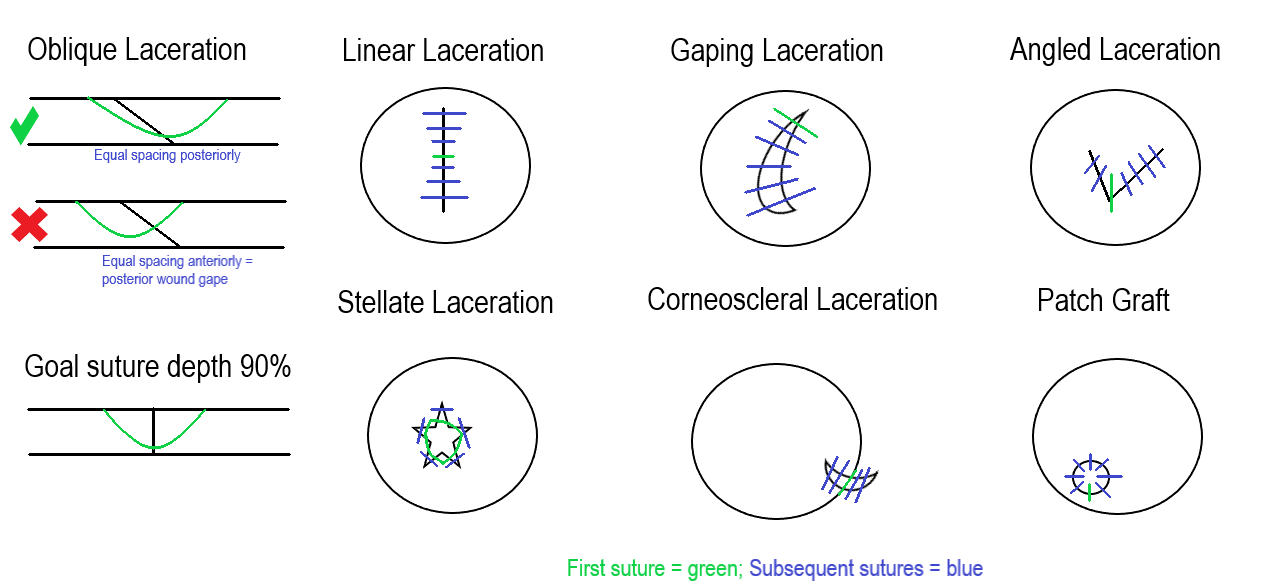

Sutures should be passed at 90% depth in the stroma because too shallow can lead to posterior wound gape. Full-thickness passes can become a track for microorganisms to enter the eye.

When determining the placement of a second suture, remember the compression zones, which are triangular extensions from the suture, to ensure there are no gaps.[22]

Long sutures will have a large zone of compression compared to shorter sutures. Long sutures should be passed in the periphery to steepen the cornea centrally and seal the wound. Centrally the sutures are in the visual axis. Placing short sutures centrally with minimal suture tension will reduce astigmatism and prevent excess scarring.

Managing Tissue Prolapse

Following the pressure gradient, the iris and vitreous will prolapse through a corneal laceration until closure. It is important to avoid incorporating the tissue into the closure. There are several methods for managing prolapsed tissue. One strategy is to create a paracentesis away from the wound with a surgical blade and inject a viscoelastic. Use a cyclodialysis spatula to pull the iris back into the eye through a sweeping motion. Repositioning the intraocular tissue may be necessary throughout the suturing process. Accidental pressure on the globe when passing a suture or gaping the wound with instruments tends to protrude more tissue. If the patient is phakic, it is paramount to protect the lens and avoid violating the capsule.

The following are general guidelines for various scenarios—drawings depicted in the attached figure highlight each situation.

Oblique laceration: The suture will be an equal distance at the posterior part of the wound, but anteriorly will look displaced to one side. Avoid tension over the shallow side of the wound when tying the suture.

Linear laceration: Start suture placement in the center of the laceration and then bisect the halves until sealed.

Gaping laceration: Place the initial suture at the ends of the wound and then zip it up, keeping tissue out of the closure.

Angled laceration: The initial suture can be placed at the apex, then suture the sides as separate linear lacerations.

Stellate laceration: These closures can be challenging. A purse-string suture is placed centrally, either at the beginning or end of the closure, to help seal it. Interrupted sutures close the remaining aspects of the laceration.

Corneoscleral laceration: Place the initial suture at the limbus. This alignment is critical to repairing the cornea and scleral aspects. The limbus is usually the most identifiable tissue during the repair because of the contrast between the cornea and sclera. After closing the limbus, focus on the corneal aspect first and then the sclera to avoid tissue prolapse.

Tissue loss: When tissue is absent, a patch graft can create a watertight closure. There are various techniques for a patch graft that incorporate amniotic membrane, allograft tissue, or gamma-irradiated cornea.[23][24][25]

Finishing up

Once the corneal laceration repair is complete, test it for a leak with surgical spears or a fluorescein strip. If a leak is present, continue to suture or add adjuncts such as cyanoacrylate or fibrin glue, amniotic membrane, or contact lens. Ensure all knots are buried, ideally away from the visual axis.

A combination of intracameral, subconjunctival, topical, intravenous, and oral antibiotics decreases the risk of infections after the repair.

Patch the eye with surgical eye pads and cover it with a rigid eye shield.

Complications

Complications are avoidable with preoperative and postoperative antibiotics and proper intraoperative surgical technique.

Posttraumatic Endophthalmitis

Posttraumatic endophthalmitis is a devastating condition that occurs from 3.3% to 17% in penetrating trauma. The primary risk factors are a delay of primary surgical repair and violation of the lens capsule. The diagnosis can be difficult because the eye is already inflamed from the trauma and surgery.[26] Symptoms can be non-specific, including ocular pain, redness, eyelid swelling, discharge, decreased vision, and floaters. Treatment recommendations vary from a vitreous tap and injection with broad-spectrum antibiotics to a vitrectomy if vision is light perception or worse.[27]

Retained Intraocular Foreign Body

Intraocular foreign bodies in ocular trauma occur from 18 to 41%.[28] Ocular imaging prior to the surgical repair can identify foreign bodies. Sometimes foreign bodies can not be removed during a surgical repair, especially if located in the vitreous, so that further surgery may be necessary. Most foreign bodies are metallic and toxic to the eye; therefore, removal is recommended.[28]

Wound Leak

Evaluate the patient the day after the primary surgical repair with fluorescein to check for a wound leak. If a wound leak is present, a bandage contact lens or cyanoacrylate glue may seal it. If the leak is too brisk or large, more suturing is required to create a watertight closure. Wound leaks significantly increase the risk of infection.[29]

Suture Issues

Unburied knots and broken or loose sutures can cause the patient discomfort and serve as a track for microorganisms. All suture knots should be buried at the time of surgery; however, if recognized during the postoperative period, a knot can be rotated at the slit lamp. The timing of suture removal is variable depending on the patient's age, size of the laceration, and refractive anomaly induced by the suture.[30] However, remove broken or loose sutures immediately.

Iris Damage

The iris can tear or dislodge from its root through the initial trauma or during surgical repair. An abnormal iris can cause photophobia, visual disturbances, and an unpleasant aesthetic appearance.[31][32] Surgical techniques, corneal tattooing, contact lens, and artificial iris implants are available if the patient is symptomatic.[33][34]

Cataract

Cataracts can form from the initial trauma or during the operative repair if the lens capsule is violated. The majority of traumatic cataracts can safely be removed and replaced with a posterior or scleral-fixated lens to improve vision.[35]

Infectious Keratitis

Infectious keratitis can occur following trauma by various organisms.[36] Bacteria can build up on the sutures or form abscesses.[37] Treatment typically starts with fluoroquinolones, although fortified broad-spectrum antibiotics may be necessary for severe infections or resistant bacteria.

Retinal Detachment

Retinal detachments can occur during the trauma or subsequently in the postoperative period. Early intervention is key to preventing vision loss.

Posttraumatic Glaucoma

It is not uncommon for secondary glaucoma to occur from penetrating trauma due to various mechanisms.[38] Monitor the intraocular pressure during the postoperative period and counsel the patient about the long-term risk.

Sympathetic Ophthalmia

Sympathetic ophthalmia is an uncommon immune reaction that occurs in the non-traumatic eye after injuries or surgeries involving the uveal tissue.[39] Suspect this condition if inflammation occurs in the non-traumatic eye. The classic doctrine taught was to enucleate the traumatic eye within two weeks to prevent this condition; however, the current doctrine encourages leaving the traumatic eye in place if there is any vision still present.[40]

Vision Loss

Vision loss can occur from all of the complications discussed in this section. Traumatic damage to the optic nerve or other parts of the eye can also lead to vision loss. Corneal scarring, neovascularization, and irregular astigmatism are common reasons for decreased vision after a corneal laceration. Hard contact lenses can be helpful to determine if the visual complaint is related to the cornea versus other parts of the eye. A special fit contact lens can often improve vision significantly.[41] If the vision loss is related to corneal pathology and not improved with a contact lens, a corneal transplant may be beneficial once the eye has completely healed from the trauma.[42]

Clinical Significance

Visual acuity loss is detrimental to the quality of life.[43] The United States Eye Registry highlights at least a quarter of the patients with ocular trauma will have permanent vision loss.[44] Despite a perfect corneal laceration repair, vision loss may be present from corneal scarring, astigmatism, or damage to other parts of the eye.

Prevention with eye protection leads to the best vision outcomes and fewer injuries.[45][46][47] The mandate for eye protection in the U.S. military led to fewer and less severe ocular injuries.[48] In a patient with vision loss, eye protection is strongly recommended to protect the better-seeing eye. After ocular trauma, educating patients on protective eyewear should be incorporated into practice patterns.[49]

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Improving outcomes for ocular trauma, including corneal lacerations, requires a team approach. Although the ophthalmologist performs the repair, many others help throughout the process. The initial step in the process is identifying a corneal laceration. Prompt recognition of an ocular injury by a bystander at the scene of the injury, paramedic, emergency room nurse, physician, or optometrist expedites the repair. After identifying the corneal laceration, cover the eye with a rigid eye shield to prevent further damage, and transfer the patient to an ophthalmologist. Occasionally, a patient is incorrectly diagnosed with a corneal abrasion which can delay the repair. In the ocular blast injuries from the Boston Marathon bombing and the West Texas fertilizer explosion, only 28% of the patients had ophthalmology consulted from the emergency room.[50]

The patient and family members almost always want to know if the patient’s vision will return to normal. Based on the United States Eye Registry, over 27% of the injuries involved permanent vision impairment. The Ocular Trauma Score is a tool for predicting the final vision of the injured eye and can be used by the team to educate the patient or their family.[51]

Nurses are vital members of the interprofessional group as they will monitor the patient’s vital signs, especially the pain level, pre-operatively and post-operatively. The radiologist has a role in identifying foreign bodies on facial computed tomography and can often confirm an open globe injury.[52] The pharmacist ensures the patient is on the correct analgesics, antiemetics, and antibiotics. If an infection is present or develops in the postoperative course, specialized fortified antibiotics may need to be compounded by the pharmacist.

The surgeon, surgical technician, operating nurse, and anesthesia provider all have roles in the outcome of the surgery. A well-organized surgical timeout that all members participate in improves patient safety. In the surgical repair, the surgical technician passes instruments to the surgeon, prevents needle stick injuries, and ensures correct needle counts. The anesthesia provider is vital to prevent the patient from moving during the surgical repair. Abrupt movements from the patient can lead to tissue protrusion and worsen the injury.

All team members educate the patient and family about postoperative care to include compliance with medications, signs of complications, activity limitations, and expected symptoms throughout the recovery process. Setting realistic expectations is important because many cases result in poor outcomes.[53]

A corneal laceration will change the refractive error of the patient. The patient may need a special contact lens fitting by an optometrist or an update in their prescription glasses to improve the visual outcome. The technological advances in contact lenses have improved patient visual outcomes after ocular trauma. A study of 214 patients with an open globe injury demonstrated a visual acuity improvement in 97% of the patients with a contact lens.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Interventions

The first person to recognize an eye injury should intervene and place a rigid eye shield over the eye. Nurses are vital in keeping the patient calm before the repair. Control of pain and nausea before and after the repair is necessary. Antibiotics should be administered at the onset of the injury and continued throughout the recovery period.

Any member of the care team should speak up if they notice anything unsafe or have any concerns.

Nursing, Allied Health, and Interprofessional Team Monitoring

Monitoring a patient's pain, nausea, and other vitals should occur before and after the repair. After the repair, the patient is either discharged home with a follow-up visit the next day in the clinic or kept overnight in the hospital for observation. During the postoperative period, especially the first week, all team members should monitor for signs of infection such as increased pain or decreased vision.

On the day of discharge, clear instructions from every team member to educate the patient about follow-up are paramount because many ocular trauma patients will not return.[54]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Swain T, McGwin G Jr. The Prevalence of Eye Injury in the United States, Estimates from a Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmic epidemiology. 2020 Jun:27(3):186-193. doi: 10.1080/09286586.2019.1704794. Epub 2019 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 31847651]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceVlasov A, Ryan DS, Ludlow S, Coggin A, Weichel ED, Stutzman RD, Bower KS, Colyer MH. Corneal and Corneoscleral Injury in Combat Ocular Trauma from Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. Military medicine. 2017 Mar:182(S1):114-119. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-16-00041. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28291461]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMacsai MS. The management of corneal trauma: advances in the past twenty-five years. Cornea. 2000 Sep:19(5):617-24 [PubMed PMID: 11009314]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVote BJ,Elder MJ, Cyanoacrylate glue for corneal perforations: a description of a surgical technique and a review of the literature. Clinical [PubMed PMID: 11202468]

Beatty RF, Beatty RL. The repair of corneal and scleral lacerations. Seminars in ophthalmology. 1994 Sep:9(3):165-76 [PubMed PMID: 10155636]

Koster HR, Kenyon KR. Complications of surgery associated with ocular trauma. International ophthalmology clinics. 1992 Fall:32(4):157-78 [PubMed PMID: 1399345]

DelMonte DW, Kim T. Anatomy and physiology of the cornea. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 2011 Mar:37(3):588-98. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.12.037. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21333881]

Ahmadi AJ,Jakobiec FA, Corneal wound healing: cytokines and extracellular matrix proteins. International ophthalmology clinics. 2002 Summer; [PubMed PMID: 12131579]

Yang AY, Chow J, Liu J. Corneal Innervation and Sensation: The Eye and Beyond. The Yale journal of biology and medicine. 2018 Mar:91(1):13-21 [PubMed PMID: 29599653]

Weider L, Hughes K, Ciarochi J, Dunn E. Early versus delayed repair of facial fractures in the multiply injured patient. The American surgeon. 1999 Aug:65(8):790-3 [PubMed PMID: 10432093]

Mazzoli RA, Gross KR, Butler FK. The use of rigid eye shields (Fox shields) at the point of injury for ocular trauma in Afghanistan. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2014 Sep:77(3 Suppl 2):S156-62. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000391. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25159350]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBenson WH,Snyder IS,Granus V,Odom JV,Macsai MS, Tetanus prophylaxis following ocular injuries. The Journal of emergency medicine. 1993 Nov-Dec; [PubMed PMID: 8157904]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceParunović AB, Popović BA. Antibiotic prophylaxis in penetrating injuries of the eye. Albrecht von Graefes Archiv fur klinische und experimentelle Ophthalmologie. Albrecht von Graefe's archive for clinical and experimental ophthalmology. 1976 May 26:199(3):277-9 [PubMed PMID: 1084710]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceScott R. The injured eye. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2011 Jan 27:366(1562):251-60. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0234. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21149360]

Campbell TD, Gnugnoli DM. Seidel Test. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 31082063]

Isenberg SJ, The ocular application of povidone-iodine. Community eye health. 2003; [PubMed PMID: 17491857]

Lodhi O, Tripathy K. Anesthesia for Eye Surgery. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 34283497]

Kohli R, Ramsingh H, Makkad B. The anesthetic management of ocular trauma. International anesthesiology clinics. 2007 Summer:45(3):83-98 [PubMed PMID: 17622831]

Tan J, Foster LJR, Watson SL. Corneal Sealants in Clinical Use: A Systematic Review. Current eye research. 2020 Sep:45(9):1025-1030. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2020.1764052. Epub 2020 May 27 [PubMed PMID: 32460646]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceZhang T,Jia Y,Li S,Shi W, Individualized Corneal Patching for Treatment of Corneal Trauma Combined with Tissue Defects. Journal of ophthalmology. 2020; [PubMed PMID: 33299602]

Sharma A, Kaur R, Kumar S, Gupta P, Pandav S, Patnaik B, Gupta A. Fibrin glue versus N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate in corneal perforations. Ophthalmology. 2003 Feb:110(2):291-8 [PubMed PMID: 12578769]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMatalia HP, Nandini C, Matalia J. Surgical technique for the management of corneal perforation in brittle cornea. Indian journal of ophthalmology. 2021 Sep:69(9):2521-2523. doi: 10.4103/ijo.IJO_2542_20. Epub [PubMed PMID: 34427257]

Krysik K, Dobrowolski D, Wylegala E, Lyssek-Boron A. Amniotic Membrane as a Main Component in Treatments Supporting Healing and Patch Grafts in Corneal Melting and Perforations. Journal of ophthalmology. 2020:2020():4238919. doi: 10.1155/2020/4238919. Epub 2020 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 32148944]

Ashena Z,Holmes C,Nanavaty MA, Pericardium Patch Graft for Severe Corneal Wound Burn. Journal of current ophthalmology. 2021 Jul-Sep; [PubMed PMID: 34765825]

Daoud YJ, Smith R, Smith T, Akpek EK, Ward DE, Stark WJ. The intraoperative impression and postoperative outcomes of gamma-irradiated corneas in corneal and glaucoma patch surgery. Cornea. 2011 Dec:30(12):1387-91. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31821c9c09. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21993467]

El Chehab H, Renard JP, Dot C. [Post-traumatic endophthalmitis]. Journal francais d'ophtalmologie. 2016 Jan:39(1):98-106. doi: 10.1016/j.jfo.2015.08.005. Epub 2015 Nov 10 [PubMed PMID: 26563842]

Sheu SJ. Endophthalmitis. Korean journal of ophthalmology : KJO. 2017 Aug:31(4):283-289. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2017.0036. Epub 2017 Jun 28 [PubMed PMID: 28752698]

Loporchio D,Mukkamala L,Gorukanti K,Zarbin M,Langer P,Bhagat N, Intraocular foreign bodies: A review. Survey of ophthalmology. 2016 Sep-Oct; [PubMed PMID: 26994871]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTong AY, Gupta PK, Kim T. Wound closure and tissue adhesives in clear corneal incision cataract surgery. Current opinion in ophthalmology. 2018 Jan:29(1):14-18. doi: 10.1097/ICU.0000000000000431. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28902719]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHamill MB. Corneal and scleral trauma. Ophthalmology clinics of North America. 2002 Jun:15(2):185-94 [PubMed PMID: 12229235]

Kaufman SC, Insler MS. Surgical repair of a traumatic iridodialysis. Ophthalmic surgery and lasers. 1996 Nov:27(11):963-6 [PubMed PMID: 8938808]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMikhail M,Koushan K,Sharda RK,Isaza G,Mann KD, Traumatic aniridia in a pseudophakic patient 6 years following surgery. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2012; [PubMed PMID: 22347795]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReed JW. Corneal tattooing to reduce glare in cases of traumatic iris loss. Cornea. 1994 Sep:13(5):401-5 [PubMed PMID: 7995061]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMayer CS, Reznicek L, Hoffmann AE. Pupillary Reconstruction and Outcome after Artificial Iris Implantation. Ophthalmology. 2016 May:123(5):1011-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2016.01.026. Epub 2016 Feb 28 [PubMed PMID: 26935356]

Blum M, Tetz MR, Greiner C, Voelcker HE. Treatment of traumatic cataracts. Journal of cataract and refractive surgery. 1996 Apr:22(3):342-6 [PubMed PMID: 8778368]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceStefan C, Nenciu A. Post-traumatic bacterial keratitis--a microbiological prospective clinical study. Oftalmologia (Bucharest, Romania : 1990). 2006:50(3):118-22 [PubMed PMID: 17144518]

Adler E, Miller D, Rock O, Spierer O, Forster R. Microbiology and biofilm of corneal sutures. The British journal of ophthalmology. 2018 Nov:102(11):1602-1606. doi: 10.1136/bjophthalmol-2018-312133. Epub 2018 Aug 12 [PubMed PMID: 30100555]

Jones WL. Posttraumatic glaucoma. Journal of the American Optometric Association. 1987 Sep:58(9):708-15 [PubMed PMID: 3502262]

Subudhi P, Kanungo S, Subudhi BN. AN ATYPICAL CASE OF SYMPATHETIC OPHTHALMIA AFTER LIMBAL CORNEAL LACERATION. Retinal cases & brief reports. 2017 Spring:11(2):141-144. doi: 10.1097/ICB.0000000000000313. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27124790]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePaulbuddhe V, Addya S, Gurnani B, Singh D, Tripathy K, Chawla R. Sympathetic Ophthalmia: Where Do We Currently Stand on Treatment Strategies? Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2021:15():4201-4218. doi: 10.2147/OPTH.S289688. Epub 2021 Oct 20 [PubMed PMID: 34707340]

Scanzera AC, Dunbar G, Shah V, Cortina MS, Leiderman YI, Shorter E. Visual Rehabilitation With Contact Lenses Following Open Globe Trauma. Eye & contact lens. 2021 May 1:47(5):288-291. doi: 10.1097/ICL.0000000000000756. Epub [PubMed PMID: 33181528]

Nobe JR, Moura BT, Robin JB, Smith RE. Results of penetrating keratoplasty for the treatment of corneal perforations. Archives of ophthalmology (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1990 Jul:108(7):939-41 [PubMed PMID: 2369351]

Brown GC. Vision and quality-of-life. Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society. 1999:97():473-511 [PubMed PMID: 10703139]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKuhn F, Morris R, Witherspoon CD, Mann L. Epidemiology of blinding trauma in the United States Eye Injury Registry. Ophthalmic epidemiology. 2006 Jun:13(3):209-16 [PubMed PMID: 16854775]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHenderson D. Ocular trauma: one in the eye for safety glasses. Archives of emergency medicine. 1991 Sep:8(3):201-4 [PubMed PMID: 1930506]

Ong HS, Barsam A, Morris OC, Siriwardena D, Verma S. A survey of ocular sports trauma and the role of eye protection. Contact lens & anterior eye : the journal of the British Contact Lens Association. 2012 Dec:35(6):285-7. doi: 10.1016/j.clae.2012.07.007. Epub 2012 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 22898257]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHoskin AK, Mackey DA, Keay L, Agrawal R, Watson S. Eye Injuries across history and the evolution of eye protection. Acta ophthalmologica. 2019 Sep:97(6):637-643. doi: 10.1111/aos.14086. Epub 2019 Mar 25 [PubMed PMID: 30907494]

Thomas R, McManus JG, Johnson A, Mayer P, Wade C, Holcomb JB. Ocular injury reduction from ocular protection use in current combat operations. The Journal of trauma. 2009 Apr:66(4 Suppl):S99-103. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31819d8695. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19359977]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBoss JD,Shah CT,Elner VM,Hassan AS, Assessment of Office-Based Practice Patterns on Protective Eyewear Counseling for Patients With Monocular Vision. Ophthalmic plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2015 Sep-Oct; [PubMed PMID: 25393903]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYonekawa Y, Hacker HD, Lehman RE, Beal CJ, Veldman PB, Vyas NM, Shah AS, Wu D, Eliott D, Gardiner MF, Kuperwaser MC, Rosa RH Jr, Ramsey JE, Miller JW, Mazzoli RA, Lawrence MG, Arroyo JG. Ocular blast injuries in mass-casualty incidents: the marathon bombing in Boston, Massachusetts, and the fertilizer plant explosion in West, Texas. Ophthalmology. 2014 Sep:121(9):1670-6.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2014.04.004. Epub 2014 May 17 [PubMed PMID: 24841363]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKuhn F, Maisiak R, Mann L, Mester V, Morris R, Witherspoon CD. The Ocular Trauma Score (OTS). Ophthalmology clinics of North America. 2002 Jun:15(2):163-5, vi [PubMed PMID: 12229231]

Sung EK, Nadgir RN, Fujita A, Siegel C, Ghafouri RH, Traband A, Sakai O. Injuries of the globe: what can the radiologist offer? Radiographics : a review publication of the Radiological Society of North America, Inc. 2014 May-Jun:34(3):764-76. doi: 10.1148/rg.343135120. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24819794]

Engelhard SB,Salek SS,Justin GA,Sim AJ,Woreta FA,Reddy AK, Malpractice Litigation in Ophthalmic Trauma. Clinical ophthalmology (Auckland, N.Z.). 2020; [PubMed PMID: 32764863]

Aaland MO, Marose K, Zhu TH. The lost to trauma patient follow-up: a system or patient problem. The journal of trauma and acute care surgery. 2012 Dec:73(6):1507-11. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31826fc928. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23147179]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence