Introduction

The laryngopharynx, also referred to as the hypopharynx, is the most caudal portion of the pharynx and is a crucial connection point through which food, water, and air pass. Specifically, it refers to the point at which the pharynx divides anteriorly into the larynx and posteriorly into the esophagus. The act of swallowing, or deglutination, is a complex multistep process performed by several essential structures in the oral cavity, pharynx, and larynx. Swallowing ensures proper transport of food and water posteriorly into the esophagus at the level of the laryngopharynx. Although the laryngopharynx’s primary physiologic function is as a cavity through which air, water, and food pass from the oral cavity to their respective destinations, it also contains structures that play an important role in speech.

The laryngopharynx is a clinically important anatomical location because of the high proportion of pharyngeal cancers that originate there. The pyriform sinus is the most frequent site of laryngopharyngeal cancer, with squamous cell carcinoma accounting for 95% of cases. The laryngopharynx is also clinically relevant due to a disorder related to the retrograde flow of digestive stomach contents to the laryngopharynx, known as laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR).

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

STRUCTURE:

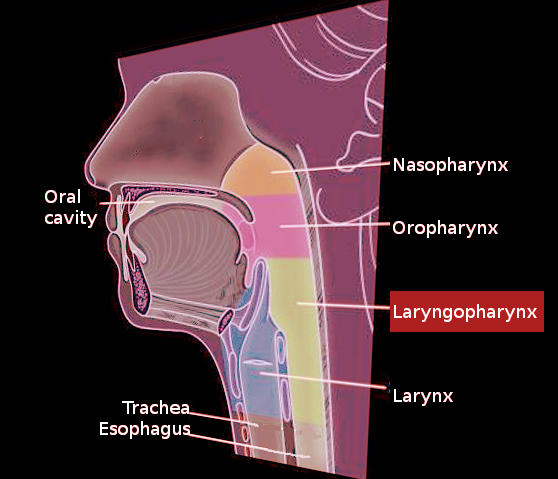

The pharynx is located posteriorly to the nasal and oral cavities and functions as a cavity through which food and air pass to the esophagus and larynx, respectively. The pharynx is made up of three separate regions: the nasopharynx, oropharynx, and laryngopharynx.

Nasopharynx:

The nasopharynx is the most rostral portion of the pharynx and refers to the region between the base of the cranium and the soft palate. It contains the opening of the Eustachian tubes that connect the pharynx to the middle ear. It also includes the adenoids and tubal tonsils, which are lymphoid tissues that play an essential role in the immune system.

Oropharynx:

The oropharynx is posterior to the oral cavity, between the soft palate and the pharyngoepiglottic fold. Important structures within the oropharynx include the soft palate, tonsils, base of the tongue, and pharyngeal bands, which are nodules of lymphoid tissue. The laryngopharynx is the final pharyngeal cavity and is located inferiorly to the oropharynx.[1]

Laryngopharynx (Hypopharynx):

The laryngopharynx;s position is inferior to the epiglottis and is bordered by the pharyngoepiglottic fold superiorly and the upper esophageal sphincter inferiorly. It refers to the portion of the pharynx where the cavity diverges anteriorly into the larynx and posteriorly into the esophagus. It contains three main structures: the posterior pharyngeal wall, pyriform sinuses, and the post-cricoid area. The pyriform sinuses, which play an essential role in speech, are two pear-shaped recesses located on either side of the laryngeal orifice. Medially to the pyriform sinuses lie the aryepiglottic folds. Thyroid cartilage lies lateral to the laryngopharynx.[1]

The pharyngeal cavity is lined by mucosa and is surrounded by skeletal muscle. The pharyngeal wall is made up of three distinct layers of tissue. The inner layer that comes in direct contact with the pharyngeal cavity is composed of stratified squamous epithelium. Next, there is the fascial layer, composed of the pharyngo-basilar fascia. Although the fascial layer is thick superiorly, it gradually decreases in thickness as it travels inferiorly, eventually disappearing by the time it reaches the upper esophageal sphincter. The upper esophageal sphincter also referred to as the inferior pharyngeal sphincter, is made up of muscles that function in preventing the entry of air into the esophagus and reflux of gastric contents into the larynx and pharynx. It is made up mostly of cricopharyngeus muscle, along with thyropharyngeus muscle and cervical esophagus. Superficial to the fascial layer, there is an outer muscular layer, which is composed of constrictors and elevators responsible for propelling food from the oral cavity to the esophagus.[2]

FUNCTION:

Structures located adjacent to the laryngopharynx play an essential role in ensuring proper transit of food and liquids from the oral cavity to the stomach. Normal swallowing physiology is vital in preventing aspiration of food and liquids into the lungs, which could lead to complications such as pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and acute respiratory failure. The act of swallowing involves three stages: oral, pharyngeal, and esophageal. During the pharyngeal stage, the soft palate elevates and comes into contact with the posterior and lateral walls of the pharynx, thereby closing off the nasopharynx and preventing regurgitation of food or liquids into the nasal cavity. The contraction of the pharyngeal constrictors propels the bolus downwards towards the esophagus. Food entering the laryngopharynx is selectively propelled posteriorly towards the esophagus by several different mechanisms that are vital to ensuring adequate airway protection. Contraction of the thyrohyoid and suprahyoid muscles cause the hyoid bone and larynx to elevate and move anteriorly. The epiglottis slopes backward, thereby sealing off the larynx. The vocal folds close to seal-off the glottis. The arytenoids tilt forward. Finally, the upper esophageal sphincter relaxes, allowing entry of food and liquids into the esophagus.[3]

Embryology

The pharynx and oral cavity derive from the branchial apparatus beginning in the fourth and fifth week of development. The embryonic pharynx develops into the branchial apparatus, which is composed of five pairs of pouches, arches, and clefts. These structures eventually develop into almost all of the structures within the head and neck. The pouches are located medially and eventually form into endoderm. The clefts are located laterally and develop into ectoderm. The arches are located in between the pouches and clefts and develop into the mesoderm, which eventually forms the cartilage, muscles, and nerves of the head and neck. The fourth and sixth arches develop into the cartilaginous structures that make up the larynx, which includes the arytenoids, cricoid, cuneiform, and thyroid cartilage. The 4th arch develops into most of the pharyngeal constrictors, the cricothyroid muscle, and the levator veli palatini muscle. The 4th arch also develops into the superior laryngeal branch of the Vagus nerve (CN 10).[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The blood supply to the laryngopharynx is via the ascending pharyngeal artery, inferior thyroid artery, and superior thyroid artery. The ascending pharyngeal artery branches medially off of the external carotid artery (ECA) and courses between the ECA and internal carotid artery as it ascends towards the pharynx. The superior thyroid artery originates from the ECA at the level of the carotid bifurcation. The inferior thyroid artery develops from the thyrocervical trunk and eventually anastomoses with the superior thyroid artery.

The venous drainage of the pharynx is via the venous plexus that drains directly into the internal jugular veins.[5]

Nerves

The Vagus nerve and its branches supply the pharyngeal constrictors. The nucleus of cranial nerve X (CN X) is in the medulla in the brainstem. It exits the skull via the jugular foramen before synapsing at the pharyngeal plexus.[5] The pharyngeal plexus, which lies along with the middle constrictor, is formed mostly from cranial nerves IX and X, with some innervation by the maxillary distribution of the trigeminal nerve (CN V2). The plexus contains both sensory and motor neurons. Sensory innervation of the laryngopharynx begins in pharyngeal branches of the vagus nerve, which ultimately synapse at the pharyngeal plexus.[6] Arnold's nerve, a branch of the vagus nerve, also has sensory branches that supply the external auditory canal. Therefore, patients with laryngeal cancer can have referred otalgia.

Muscles

Pharyngeal constrictors surround the pharynx posteriorly and laterally, meeting midline at the posterior raphe. The pharyngeal constrictors are comprised of three circularly oriented muscles, the superior, medial, and inferior constrictors, that function to propel food and water from the oropharynx through the laryngopharynx, and on to the esophagus. Although oriented circularly around the pharynx, constrictors are arranged longitudinally, which aids in maintaining the airway within the pharynx.

Elevator muscles, which include the palatopharyngeus, stylopharyngeus, and salpingopharyngeus, aid in swallowing by pulling the larynx up behind the base of the tongue, thereby protecting the airway. Elevation of the laryngopharynx also functions in shortening the pharynx during swallowing to improve the passage of food and liquids.[7]

The specific constrictor muscle that is in the vicinity of the laryngopharynx is the inferior constrictor, which is composed of two muscles: the thyropharyngeus and cricopharyngeus. The thyropharyngeus muscle is superior to the cricopharyngeus and lies laterally and posteriorly to the laryngopharynx. Relaxation of the cricopharyngeus and thyropharyngeus allow pharyngeal contents to enter the esophagus.[5]

Surgical Considerations

Laryngopharyngectomy:

Laryngopharyngectomy, complete removal of the larynx and hypopharynx, is generally reserved as salvage therapy following chemoradiation or for patients with advanced cancers of the hypopharynx or larynx. The primary treatment for patients with laryngopharyngeal cancer is radical radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy, as these are organ-preserving treatment modalities.[8][9] If the laryngopharyngectomy is for the treatment of laryngopharyngeal cancer, it is also recommended to dissect the bilateral level II-IV neck lymph nodes. Neck dissection serves two important purposes: (1) Determine the extent of nodal involvement and (2) to access vessels used in free flap reconstruction.[10]

Surgical Fundoplication in Laryngopharyngeal Reflux:

Nissen fundoplication is a surgery classically used in the treatment of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) whereby the upper part of the stomach, known as the fundus, is wrapped around the esophagus to reinforce the lower esophageal sphincter. Some studies have demonstrated success in treating laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) with fundoplication in a subset of select patients.[11] Treatment of LPR involves a combination of dietary and lifestyle changes, as well as proton pump inhibitors (PPI). Although 50-70% of patients improve with PPIs, many patients still suffer from laryngeal irritation despite high dose PPI treatment.[12][13] Researchers hypothesize that patients who fail to improve on PPI therapy may benefit from fundoplication under the premise that reinforcement of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) may prevent low volume reflux of acid or nonacid gastric content.[14] However, a prospective controlled trial demonstrated limited improvement in laryngeal symptoms one year following fundoplication surgery for LPR.[15]

Clinical Significance

Cancer:

Studies have shown that 72% to 87% of pharyngeal cancers arise in the laryngopharynx, often referred to as hypopharyngeal cancer in the literature.[16][17] The pyriform sinus has the highest proportion of these cancers (78.3%), followed by the posterior pharyngeal wall (14%), and then the post-cricoid area (8%).[16] Cancers of the hypopharynx account for 6% of all cancer of the head and neck, more than 95% of which are squamous cell carcinoma.[18] Other hypopharyngeal cancers include spindle cell carcinoma, salivary gland carcinoma, and basaloid squamous carcinoma.[19]

Hypopharyngeal cancers are dangerous because of their late presentation and predilection for metastasizing, with more than 85% of cancers have spread beyond the laryngopharynx at the time of diagnosis. The most common site of metastasis (65%) is to regional lymph nodes. Cancer of the hypopharynx is a devastating diagnosis, with a 5-year survival rate as low as 29%.[19] The main risk factors are alcohol consumption and smoking, although other environmental exposures such as asbestos, indoor air pollution, and coal dust also have links to hypopharyngeal cancer.[20][21][22]

Hypopharyngeal cancer can present with dysphagia, a prominent neck mass, voice impairment, hoarseness, and/or referred otalgia. Treatment is a complicated multidisciplinary decision that involves collaboration among medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and head and neck surgeons. It is a highly controversial topic since there is no uniform consensus for the best approach to treatment.[23] Treatment options include radiation, chemotherapy, surgery, or a combination thereof, with surgery being the preferred therapeutic option.[24] The goal of treatment is to obtain local tumor control while simultaneously preserving the function of the many important structures located adjacent to the laryngopharynx, which is involved in speech, swallowing, and respiration. In cases of advanced disease, laryngectomy or laryngopharyngectomy may necessary.

Laryngopharyngeal reflux:

Laryngopharyngeal reflux (LPR) is a highly controversial topic due to a disagreement among otolaryngologists and gastroenterologists regarding its pathophysiology. Otolaryngologists believe that LPR is due to retrograde flow of digestive stomach contents to the laryngopharynx, leading to mucosal injury and irritation.[25] The pathophysiology of GERD is similar in that it is due to the reflux of gastric contents into the esophagus. Interestingly, LPR rarely presents with heartburn (20%) or regurgitation, even though the acid and other corrosive stomach contents must traverse the esophagus to reach the larynx. Gastroenterologists argue that low comorbidity of GERD among patients with LPR signifies that an alternate etiology must exist.

LPR is one of the most common presentations in otolaryngology clinics, with some studies demonstrating as many as 10% of visits due to symptoms secondary to LPR.[26] LPR presents with symptoms of cough, hoarseness, throat clearing, and globus sensation.[25] It is a difficult diagnosis to make due to nonspecific symptoms that mimic many other conditions that affect the larynx, including allergies, vocal abuse, smoking, infections, and alcohol abuse.[27][28] More than half of patients presenting with hoarseness have some form of the reflux-associated disease.[29][30] Complications of LPR include subglottic stenosis, contact ulcers, granulomas, and lower airway disease, among others.[31] Diagnosis is often made based on a careful history.[25] Since LPR is associated with upper aerodigestive tract cancer, a full laryngopharyngeal examination is necessary if LPR is suspected.[32][33]

Documenting response to treatment can be a challenge since there are few objective physical exam findings to determine the extent of disease. Belafsky et al. developed the Reflux Symptom Index, an LPR grading system designed to help clinicians determine the relative effect of treatment in their LPR patients.[34] Another method for evaluating the severity of symptoms and progression of the disease is through acoustic voice analysis, which measures frequency, intensity, signal-to-noise ratio, and perturbation in patients presenting with hoarseness.[29] Regardless, clinicians must often rely on subjective symptoms obtained in history as well as clinical judgment to assess response to treatment.

The first diagnostic test indicated is laryngoscopy, which typically shows nonspecific signs of laryngeal irritation that leads to redness, thickening, and edema confined to the posterior larynx.[28] Diagnosis can be confirmed using three different approaches: endoscopic observation of damaged laryngopharyngeal tissue, pH monitoring studies, or symptomatic response to empiric medical and behavioral therapy.[25]

Treatment of LPR is a combination of behavior modification and medical treatment. Patients are often initially prescribed acid-suppressing medication, such as PPIs, to aid in both treatment and diagnosis of LPR.[35] Other medical therapies include H2 receptor antagonists, mucosal cytoprotectants, and prokinetic agents. Behavior modification includes the avoidance of alcohol, smoking cessation, and weight loss. Patients should also be instructed to avoid dietary triggers such as chocolate, carbonated beverages, citrus fruits, fats, red wines, caffeine, spicy tomato products, and meals before bedtime.[36] If lifestyle changes and medical therapy fail in managing symptoms, patients with significant reflux due to lower esophageal sphincter incompetence can opt for surgical intervention. Although some otolaryngologists advocate for fundoplication, there is limited evidence demonstrating its efficacy in resolving symptoms of LPR.[15]

Media

References

Emura F, Baron TH, Gralnek IM. The pharynx: examination of an area too often ignored during upper endoscopy. Gastrointestinal endoscopy. 2013 Jul:78(1):143-9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.02.021. Epub 2013 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 23582474]

Mittal RK. Motor Function of the Pharynx, Esophagus, and its Sphincters. 2011:(): [PubMed PMID: 21634068]

Matsuo K, Palmer JB. Anatomy and physiology of feeding and swallowing: normal and abnormal. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America. 2008 Nov:19(4):691-707, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2008.06.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18940636]

Graham A. The development and evolution of the pharyngeal arches. Journal of anatomy. 2001 Jul-Aug:199(Pt 1-2):133-41 [PubMed PMID: 11523815]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDonner MW, Bosma JF, Robertson DL. Anatomy and physiology of the pharynx. Gastrointestinal radiology. 1985:10(3):196-212 [PubMed PMID: 4029536]

Sinclair WJ. Role of the pharyngeal plexus in initiation of swallowing. The American journal of physiology. 1971 Nov:221(5):1260-3 [PubMed PMID: 5124270]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceHeyd C, Yellon R. Anatomy, Head and Neck, Pharynx Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30969574]

Department of Veterans Affairs Laryngeal Cancer Study Group, Wolf GT, Fisher SG, Hong WK, Hillman R, Spaulding M, Laramore GE, Endicott JW, McClatchey K, Henderson WG. Induction chemotherapy plus radiation compared with surgery plus radiation in patients with advanced laryngeal cancer. The New England journal of medicine. 1991 Jun 13:324(24):1685-90 [PubMed PMID: 2034244]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAl-Sarraf M. Treatment of locally advanced head and neck cancer: historical and critical review. Cancer control : journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2002 Sep-Oct:9(5):387-99 [PubMed PMID: 12410178]

Iseli TA, Agar NJ, Dunemann C, Lyons BM. Functional outcomes following total laryngopharyngectomy. ANZ journal of surgery. 2007 Nov:77(11):954-7 [PubMed PMID: 17931256]

Catania RA, Kavic SM, Roth JS, Lee TH, Meyer T, Fantry GT, Castellanos PF, Park A. Laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication effectively relieves symptoms in patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract. 2007 Dec:11(12):1579-87; discussion 1587-8 [PubMed PMID: 17932726]

Vaezi MF, Hicks DM, Abelson TI, Richter JE. Laryngeal signs and symptoms and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a critical assessment of cause and effect association. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2003 Sep:1(5):333-44 [PubMed PMID: 15017651]

DeVault KR. Overview of therapy for the extraesophageal manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. The American journal of gastroenterology. 2000 Aug:95(8 Suppl):S39-44 [PubMed PMID: 10950104]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAmin MR, Postma GN, Johnson P, Digges N, Koufman JA. Proton pump inhibitor resistance in the treatment of laryngopharyngeal reflux. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2001 Oct:125(4):374-8 [PubMed PMID: 11593175]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceSwoger J, Ponsky J, Hicks DM, Richter JE, Abelson TI, Milstein C, Qadeer MA, Vaezi MF. Surgical fundoplication in laryngopharyngeal reflux unresponsive to aggressive acid suppression: a controlled study. Clinical gastroenterology and hepatology : the official clinical practice journal of the American Gastroenterological Association. 2006 Apr:4(4):433-41 [PubMed PMID: 16616347]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceUgumori T, Muto M, Hayashi R, Hayashi T, Kishimoto S. Prospective study of early detection of pharyngeal superficial carcinoma with the narrowband imaging laryngoscope. Head & neck. 2009 Feb:31(2):189-94. doi: 10.1002/hed.20943. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18853451]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFujii S, Yamazaki M, Muto M, Ochiai A. Microvascular irregularities are associated with composition of squamous epithelial lesions and correlate with subepithelial invasion of superficial-type pharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Histopathology. 2010 Mar:56(4):510-22. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03512.x. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20459558]

Koufman J, Sataloff RT, Toohill R. Laryngopharyngeal reflux: consensus conference report. Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 1996 Sep:10(3):215-6 [PubMed PMID: 8865091]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCarvalho AL, Nishimoto IN, Califano JA, Kowalski LP. Trends in incidence and prognosis for head and neck cancer in the United States: a site-specific analysis of the SEER database. International journal of cancer. 2005 May 1:114(5):806-16 [PubMed PMID: 15609302]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceHall SF, Groome PA, Irish J, O'Sullivan B. The natural history of patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx. The Laryngoscope. 2008 Aug:118(8):1362-71. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318173dc4a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18496152]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceShangina O,Brennan P,Szeszenia-Dabrowska N,Mates D,Fabiánová E,Fletcher T,t'Mannetje A,Boffetta P,Zaridze D, Occupational exposure and laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer risk in central and eastern Europe. American journal of epidemiology. 2006 Aug 15; [PubMed PMID: 16801374]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMarchand JL,Luce D,Leclerc A,Goldberg P,Orlowski E,Bugel I,Brugère J, Laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancer and occupational exposure to asbestos and man-made vitreous fibers: results of a case-control study. American journal of industrial medicine. 2000 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 10797501]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRoboson A. Evidence-based management of hypopharyngeal cancer. Clinical otolaryngology and allied sciences. 2002 Oct:27(5):413-20 [PubMed PMID: 12383309]

Chan JY, Wei WI. Current management strategy of hypopharyngeal carcinoma. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2013 Feb:40(1):2-6. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2011.11.009. Epub 2012 Jun 17 [PubMed PMID: 22709574]

Ford CN. Evaluation and management of laryngopharyngeal reflux. JAMA. 2005 Sep 28:294(12):1534-40 [PubMed PMID: 16189367]

Koufman JA. The otolaryngologic manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD): a clinical investigation of 225 patients using ambulatory 24-hour pH monitoring and an experimental investigation of the role of acid and pepsin in the development of laryngeal injury. The Laryngoscope. 1991 Apr:101(4 Pt 2 Suppl 53):1-78 [PubMed PMID: 1895864]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceTauber S, Gross M, Issing WJ. Association of laryngopharyngeal symptoms with gastroesophageal reflux disease. The Laryngoscope. 2002 May:112(5):879-86 [PubMed PMID: 12150622]

Ylitalo R, Lindestad PA, Ramel S. Symptoms, laryngeal findings, and 24-hour pH monitoring in patients with suspected gastroesophago-pharyngeal reflux. The Laryngoscope. 2001 Oct:111(10):1735-41 [PubMed PMID: 11801936]

Hopkins C, Yousaf U, Pedersen M. Acid reflux treatment for hoarseness. The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 2006 Jan 25:(1):CD005054 [PubMed PMID: 16437513]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceFord CN. Advances and refinements in phonosurgery. The Laryngoscope. 1999 Dec:109(12):1891-900 [PubMed PMID: 10591344]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMaronian NC, Azadeh H, Waugh P, Hillel A. Association of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease and subglottic stenosis. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2001 Jul:110(7 Pt 1):606-12 [PubMed PMID: 11465817]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceReavis KM, Morris CD, Gopal DV, Hunter JG, Jobe BA. Laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms better predict the presence of esophageal adenocarcinoma than typical gastroesophageal reflux symptoms. Annals of surgery. 2004 Jun:239(6):849-56; discussion 856-8 [PubMed PMID: 15166964]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMorrison MD. Is chronic gastroesophageal reflux a causative factor in glottic carcinoma? Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1988 Oct:99(4):370-3 [PubMed PMID: 3148885]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceBelafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Validity and reliability of the reflux symptom index (RSI). Journal of voice : official journal of the Voice Foundation. 2002 Jun:16(2):274-7 [PubMed PMID: 12150380]

Frye JW, Vaezi MF. Extraesophageal GERD. Gastroenterology clinics of North America. 2008 Dec:37(4):845-58, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2008.09.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19028321]

Steward DL, Wilson KM, Kelly DH, Patil MS, Schwartzbauer HR, Long JD, Welge JA. Proton pump inhibitor therapy for chronic laryngo-pharyngitis: a randomized placebo-control trial. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2004 Oct:131(4):342-50 [PubMed PMID: 15467597]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence