Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Medial Thigh Muscles

Anatomy, Bony Pelvis and Lower Limb: Medial Thigh Muscles

Introduction

The thigh has some of the largest muscles in the human body. The medial thigh muscles are essential for normal gait and lower extremity functioning. The medial thigh muscles mainly allow for adduction of the leg. Weak adductor muscles can create knee instability and increase the risk of an adductor strain.[1] The medial thigh muscles also protect important neurovascular structures as they pass from the proximal hip joint to the knee and lower leg.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The femoral triangle is a space located at the proximal thigh. Its borders are:

- Superior: inguinal ligament

- Lateral: sartorius

- Medial: adductor longus

The adductor canal is located deep to the sartorius muscle and spans the middle third of the thigh, spanning the femoral triangle proximally to the adductor hiatus distally. The contents of the adductor canal include:

- Saphenous nerve

- The nerve to vastus medialis

- Superficial femoral artery

- Femoral vein

This adductor canal allows the passage of the major thigh neurovascular bundle, traveling from the proximal thigh to the distal thigh.[2]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The femoral artery provides the main arterial supply to the lower extremity. A continuation of the external iliac artery, the common femoral artery enters the thigh, passing deep to the inguinal ligament. Once in the thigh, the femoral artery gives off several branches.[3] These are:

- Medial femoral circumflex artery

- Lateral femoral circumflex artery

- Femoral profunda (deep artery of the thigh) artery

- Medial and Lateral femoral circumflex branches

- The medial femoral circumflex artery is the predominant blood supply to the head (via the lateral epiphyseal artery)

- First, second, and third perforating branches

- Supply the medial thigh muscles

- Medial and Lateral femoral circumflex branches

- Superficial femoral artery

Nerves

The saphenous nerve enters the adductor canal at the distal apex of the femoral triangle. At this location, it is found adjacent to the femoral artery.[2] Once in the adductor canal, the saphenous nerve courses distally towards the knee joint. Unlike the femoral artery, which then enters the adductor hiatus, the saphenous nerve pierces between the gracilis and sartorius and travels superficially, eventually providing sensory innervation to the medial distal leg.[2]

The femoral nerve mostly innervates the hip flexor and knee extensor muscles. Of the muscles in the medial thigh, the femoral nerve innervates the sartorius and pectineus muscles via its anterior motor branch.

The obturator nerve comes from the lumbar plexus (second, third, and fourth lumbar levels). The anterior branch of the obturator nerve provides motor innervation to the superficial medial thigh muscles as well as sensation to the hip joint and the medial thigh. The posterior branch of the obturator nerve supplies motor innervation to the deep adductor muscles as well as sensation to the posterior knee.[4]

Muscles

The majority of the adductor muscles originate from the pubic bone and insert at various portions of the femur. The most medial muscle of the medial thigh muscles is the gracilis muscle. Although the sartorius muscle does not originate with the adductors proximally, as it travels distally, it crosses medially across the knee extenders and inserts medially on the proximal tibia. The junction where the gracilis, sartorius, and semitendinosus insert on the anteromedial proximal tibia is known as the pes anserinus. The name of this region derives from its resemblance to a goosefoot.[5]

These muscles are arranged from deep to superficial: semitendinosus, sartorius, and gracilis. Interestingly, it has been determined that 40% of the adductor longus muscle originates anteriorly near the pubic tubercle via tendon fibers, and 60% originates from the posterior pubic symphysis via muscular fibers.[6] Specific origins and insertions are described in detail below.

- Sartorius origin: Anterior superior iliac spine

- Sartorius insertion: Medial proximal tibia at the pes anserinus

- Gracilis origin: Anterior body of the pubis and inferior ramus of the pubis

- Gracilis insertion: Medial proximal tibia at the pes anserinus

- Pectineus origin: Pectineal line

- Pectineus insertion: Posterior femur from lesser trochanter to linea aspera

- Adductor brevis origin: Body of the pubic bone and anteroinferior pubic ramus

- Adductor brevis insertion: Upper third of the femur on the linea aspera and posterior proximal femur

- Adductor longus origin: Body of the pubis and anteroinferior pubic ramus

- Adductor longus insertion: Middle third of the shaft of the femur on the linea aspera

- Adductor magnus origin: Inferior pubic ramus, external obturator membrane, and ischial tuberosity.

- Adductor magnus insertion: Posterior proximal femur and linea aspera

Physiologic Variants

Several anatomic variants of the pes anserinus have been discovered. In cadaveric studies, accessory gracilis and semitendinosus were identified to insert together and separately.[5] Another study identified three variations in the arrangement of the pes anserinus tendon. The first variation found that the sartorius tendon did not cover the gracilis tendon. The second variation found that the sartorius tendon covered the gracilis tendon completely but did not completely cover the semimembranosus tendon. The third variation found that the sartorius tendon completely covered the gracilis and the semimembranosus tendons.[7]

A review of 4880 femoral angiograms revealed that 40% of patients had a high bifurcation in either of their femoral arteries. The researchers also discovered that the incidence of a contralateral high bifurcation increases in the case of a unilateral high bifurcation.[8]

Surgical Considerations

Total Knee Arthroplasty (TKA)

A femoral nerve block (FNB) and adductor canal block have been used for pain control during and after total knee arthroplasty (TKA). Both techniques provide similar analgesic benefits while mitigating the risks of general anesthesia. However, FNB has fallen out of favor due to its associated quadriceps weakness in patients postoperatively. Thus, FNB theoretically delays mobilization in this subset of patients.[9] While FNB has been shown to reduce quadriceps strength by 49%, adductor canal blocks result in significantly less (i.e., 8%) quadriceps weakness postoperatively. Adductor canal blocks preserve the ability of patients to ambulate better than a femoral block. Total analgesic consumption was 14.5% less in the adductor canal block, and postoperative pain control was comparable to the femoral canal block.[10]

Surgical Approaches to the Hip

Chiron et al. describe a minimally invasive medial hip approach that allows for visualization and access to the iliopsoas tendon and the intraarticular region without risking injury to the nerve and vascular supply. This medial hip approach is anterior to the adductor longus, adductor brevis, pectinate, and adductor magnus muscles. This surgical approach contrasts with the traditional trans-abductor approach to the hip, which passes anterior to the adductor longus and adductor brevis muscles but is posterior to the pectinate muscle. The trans-abductor approach involves a risk to the obturator nerve, which can be avoided in the medial hip approach. It is proposed that the primary indication for this approach is psoas tendon tenotomy.[11]

Hip Arthroscopy

Despite the hip joint proving to be a challenge to treat arthroscopically, the interest in arthroscopic surgery of the hip joint has increased. Major neurovascular vessels are at risk of injury, and care must be taken to preserve these structures. Specifically, medial hip portals are useful when medial hip lesions are present. The obturator nerve, medial femoral circumflex artery, and other femoral neurovascular structures are at risk of injury when medial hip portals are used.

Injury to the obturator nerve was avoided when the portals were placed in two medial locations. The first point was found by drawing a parallel line to the ilioinguinal ligament that was 3 cm distal to the ligament. This line was then crossed perpendicularly by the anterior border of the adductor longus muscle. The intersection created was the first portal location. The second portal was located 2 cm distal to the first portal along the anterior adductor longus muscle border. Injury to the medial neurovascular bundle can be further minimized by flexing the hip 40 to 50 degrees prior to inserting the medial portal.[12]

Acetabular Fractures

Acetabular fractures commonly require open reduction and internal fixation and are also known to cause impingement of the obturator nerve. The modified Stoppa approach has been popularized, and its use is common in fracture patterns requiring access to the quadrilateral plate. Fracture displacement and medial comminution in this region often occur in both associated column fracture patterns.

Overall the modified Stoppa approach is less invasive than the traditional ilioinguinal approach. Moreover, the modified Stoppa approach provides equivalent access to the quadrilateral plate compared to the traditional ilioinguinal approach. A 2017 study compared the ilioinguinal and Stoppa approaches for ORIF treatment for displaced acetabular fractures. Ultimately, both techniques achieved satisfactory clinical outcomes; the Stoppa approach demonstrated superior total operative time and intraoperative blood loss outcomes.[13]

Clinical Significance

Obturator nerve entrapment syndrome will present with sensation loss to the medial thigh, thigh adduction weakness, or both. Trauma and iatrogenic injury are the most common causes of this condition. Iatrogenic injury likely results from orthopedic, urologic, and spine surgery. Less common causes include gynecologic complications (e.g., ectopic pregnancy), sports hernias, neurofibromas, or lipomas. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be beneficial in identifying adductor brevis or adductor longus muscle atrophy which would indicate possible obturator nerve entrapment. The gold standard for diagnosis of this condition is electromyography. Treatment is typically initially conservative and can be followed by obturator nerve block or surgical intervention if unsuccessful.[4]

The incidence of groin pain is high and can be challenging to elucidate. Athletic pubalgia has been gaining increased recognition as the cause of chronic groin pain in athletes. The classic presentation is gradually increasing pain located unilaterally in the lower abdomen region, deep groin, and proximal origin of the adductors. The differential diagnosis for an injury in this region can be broad.[1] A discussion of the possible diagnosis is beyond the scope of this article, but conditions that apply directly to the medial thigh muscles will follow.

Adductor strains are some of the most common groin injuries in the athletic population. It has been estimated that 10% of all soccer injuries are attributed to this diagnosis. Resisted adduction and palpation to the affected muscle and/or tendon will elicit pain. The diagnosis is almost always made clinically, with imaging reserved mainly for chronic conditions that have been recalcitrant to treatment. Initial treatment of this condition is conservative, including nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories and rest. Depending on the specific location of the injury, either light or aggressive physical therapy can be indicated.[1]

Media

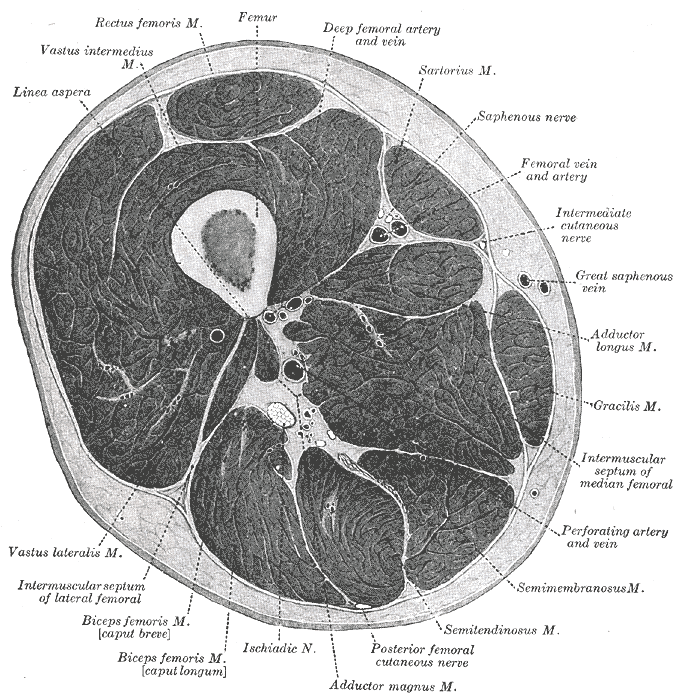

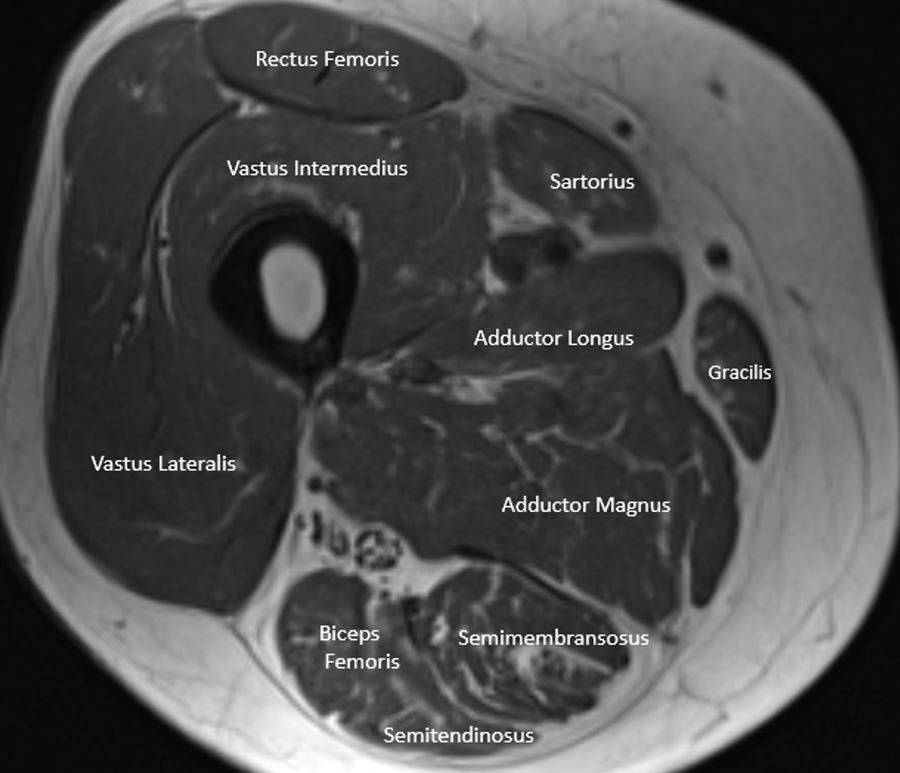

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

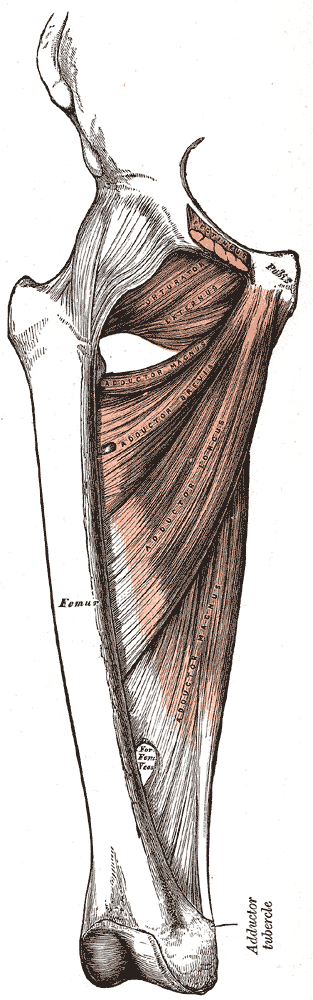

Medial Compartment of the Thigh. Shown in this illustration are the pectineus (cut), obturator externus, adductor magnus, adductor brevis, and adductor longus. Pubic bone origin and femoral insertion are also indicated.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Elattar O, Choi HR, Dills VD, Busconi B. Groin Injuries (Athletic Pubalgia) and Return to Play. Sports health. 2016 Jul:8(4):313-23. doi: 10.1177/1941738116653711. Epub 2016 Jun 14 [PubMed PMID: 27302153]

Burckett-St Laurant D, Peng P, Girón Arango L, Niazi AU, Chan VW, Agur A, Perlas A. The Nerves of the Adductor Canal and the Innervation of the Knee: An Anatomic Study. Regional anesthesia and pain medicine. 2016 May-Jun:41(3):321-7. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000389. Epub [PubMed PMID: 27015545]

Zlotorowicz M, Czubak-Wrzosek M, Wrzosek P, Czubak J. The origin of the medial femoral circumflex artery, lateral femoral circumflex artery and obturator artery. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2018 May:40(5):515-520. doi: 10.1007/s00276-018-2012-6. Epub 2018 Apr 12 [PubMed PMID: 29651567]

Jo SY, Chang JC, Bae HG, Oh JS, Heo J, Hwang JC. A Morphometric Study of the Obturator Nerve around the Obturator Foramen. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2016 May:59(3):282-6. doi: 10.3340/jkns.2016.59.3.282. Epub 2016 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 27226861]

Lee JH, Kim KJ, Jeong YG, Lee NS, Han SY, Lee CG, Kim KY, Han SH. Pes anserinus and anserine bursa: anatomical study. Anatomy & cell biology. 2014 Jun:47(2):127-31. doi: 10.5115/acb.2014.47.2.127. Epub 2014 Jun 20 [PubMed PMID: 24987549]

Pesquer L, Reboul G, Silvestre A, Poussange N, Meyer P, Dallaudière B. Imaging of adductor-related groin pain. Diagnostic and interventional imaging. 2015 Sep:96(9):861-9. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2014.12.008. Epub 2015 Mar 29 [PubMed PMID: 25823982]

Zhong S, Wu B, Wang M, Wang X, Yan Q, Fan X, Hu Y, Han Y, Li Y. The anatomical and imaging study of pes anserinus and its clinical application. Medicine. 2018 Apr:97(15):e0352. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010352. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29642176]

Gupta V, Feng K, Cheruvu P, Boyer N, Yeghiazarians Y, Ports TA, Zimmet J, Shunk K, Boyle AJ. High femoral artery bifurcation predicts contralateral high bifurcation: implications for complex percutaneous cardiovascular procedures requiring large caliber and/or dual access. The Journal of invasive cardiology. 2014 Sep:26(9):409-12 [PubMed PMID: 25198481]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBauer M, Wang L, Onibonoje OK, Parrett C, Sessler DI, Mounir-Soliman L, Zaky S, Krebs V, Buller LT, Donohue MC, Stevens-Lapsley JE, Ilfeld BM. Continuous femoral nerve blocks: decreasing local anesthetic concentration to minimize quadriceps femoris weakness. Anesthesiology. 2012 Mar:116(3):665-72. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182475c35. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22293719]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceSeo SS, Kim OG, Seo JH, Kim DH, Kim YG, Park BY. Comparison of the Effect of Continuous Femoral Nerve Block and Adductor Canal Block after Primary Total Knee Arthroplasty. Clinics in orthopedic surgery. 2017 Sep:9(3):303-309. doi: 10.4055/cios.2017.9.3.303. Epub 2017 Aug 4 [PubMed PMID: 28861197]

Chiron P, Murgier J, Cavaignac E, Pailhé R, Reina N. Minimally invasive medial hip approach. Orthopaedics & traumatology, surgery & research : OTSR. 2014 Oct:100(6):687-9. doi: 10.1016/j.otsr.2014.06.009. Epub 2014 Aug 20 [PubMed PMID: 25164350]

Kang C, Hwang DS, Hwang JM, Park EJ. Usefulness of the Medial Portal during Hip Arthroscopy. Clinics in orthopedic surgery. 2015 Sep:7(3):392-5. doi: 10.4055/cios.2015.7.3.392. Epub 2015 Aug 13 [PubMed PMID: 26330964]

Wang XJ, Lu Li, Zhang ZH, Su YX, Guo XS, Wei XC, Wei L. Ilioinguinal approach versus Stoppa approach for open reduction and internal fixation in the treatment of displaced acetabular fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Chinese journal of traumatology = Zhonghua chuang shang za zhi. 2017 Aug:20(4):229-234. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2017.01.005. Epub 2017 Jun 19 [PubMed PMID: 28709737]

Level 1 (high-level) evidence