Anatomy, Head and Neck, Levator Scapulae Muscles

Anatomy, Head and Neck, Levator Scapulae Muscles

Introduction

The levator scapulae muscles are superficial extrinsic muscles of the back that primarily function to elevate the scapulae. Levator comes from the Latin levare, meaning "to raise." Scapulae refer to the scapulas, or shoulder blades, possibly originating from the Greek "skaptein," meaning "to dig." In conjunction with other posterior axial-appendicular muscles, the levator scapulae can inferiorly rotate the glenoid cavity and extend and laterally flex the neck. The levator scapulae also serve a role in connecting the axial skeleton with the superior appendicular skeleton. The levator scapulae can be involved in numerous pathologies, including snapping scapula syndrome, levator scapulae syndrome, Sprengel deformity, cervical myofascial pain, and fibromyalgia.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The levator scapulae muscle originates from the posterior tubercles of transverse processes of C1 (atlas), C2 (axis), C3, and C4 vertebrae.[1][2] The muscle inserts on the posterior lip of the medial scapular border, typically between the superior angle and root of the scapular spine.[3][4] The sternocleidomastoid and trapezius overlay the superior and inferior aspects of the levator scapulae, respectively, with the levator scapulae comprising part of the floor of the posterior triangle of the neck.[5]

The primary action of the levator scapulae is to elevate the scapula. The levator scapula works in conjunction with the trapezius and rhomboid muscles to accomplish this motion. The levator scapulae, along with the descending fibers of the trapezius, latissimus dorsi, rhomboids, pectoralis major and minor, and gravity, also inferiorly rotates the scapula, depressing the glenoid cavity.[6][7] The levator scapulae muscle also assists in neck extension, ipsilateral rotation, and lateral flexion.[8]

Embryology

Levator scapulae muscles derive from the paraxial mesoderm along with the rhomboid major and minor. Their development is induced by tailbud neuromesodermal progenitors by fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and Wnt signaling. The dorsal scapular nerve derives from the anterior (motor) rami of C5. The anterior root forms from the basal plate region of the spinal cord.[9][10]

Anatomic variation of the subclavian artery can be implicated in failed supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks. Clinicians perform supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks for analgesia and anesthesia of the upper limb. Kohli et al. present a case of a variant branch of the subclavian artery visualized on ultrasound, which is hypothesized to be the dorsal scapular artery, passing through the brachial plexus nerve bundle.[11]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Dorsal Scapular Artery

The dorsal scapular artery is the predominant blood supply of the levator scapulae muscle. The origin is currently in dispute in the literature. The origin most frequently cited is the subclavian artery, with the second most common being a branch of the thyrocervical trunk.[12] The transverse cervical artery, a branch of the thyrocervical trunk, divides into the superior and deep branches at the level of the levator scapulae.[6] The deep branch of the transverse cervical artery is also known as the dorsal scapular artery.[13]

Anatomic Variation

Anatomic variation of the subclavian artery has implications for failed supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks. Supraclavicular brachial plexus blocks are useful for analgesia and anesthesia of the upper limb. Kohli et al. present a case of a variant branch of the subclavian artery visualized on ultrasound. They hypothesized it could be the dorsal scapular artery passing through the brachial plexus nerve bundle.[11]

Lymphatics

Generally, the shoulder blade is associated with the axillary and supraclavicular lymph nodes. The lymph nodes from the right scapula drain into the right lymphatic duct. The left scapula drains directly into the thoracic duct.[7]

Nerves

Dorsal Scapular Nerve

The innervation of the levator scapulae is typically from the dorsal scapular nerve, or DSN, originating from the C4 and C5 nerve roots. This nerve also provides motor innervation to the rhomboids. The DSN arises from the anterior rami of the C5 root, from the upper brachial plexus, and is typically the first nerve branch off the C5 root. Innervation can also be from cervical nerves (C3, C4) via the cervical plexus.[7][14]

Physiologic Variants

There are reports of anatomic variations of the levator scapulae origin and insertion. The clinical implications and significance are not definite.[2][6][15][16][17]

Surgical Considerations

Eden-Lange Procedure

Few surgical procedures primarily involve the levator scapulae. The Eden-Lange procedure, first described in 1924, aims to recreate the functionality lost in trapezius muscle palsy, better known by the eponym "winged scapula." The tendon of the levator scapulae is transferred to the acromion, while the rhomboids are attached to the infraspinatus fossa.[4]

Modified Eden-Lange Procedure

The Modified Eden-Lange procedure is a variant also performed to reproduce native scapular positioning. Instead of transferring the rhomboid to the center of the scapula, the surgeon transfers the rhomboid minor to the supraspinatus fossa, and the rhomboid major is attached to the infraspinatus fossa. The levator scapulae muscle is then attached to the spine of the scapula.[4][18]

Thoracotomy

The levator scapulae have been reportedly implicated in thoracotomy for excision of the lung. A common deep aponeurosis covering the levator scapulae and serratus anterior must be recognized and released to avoid functional consequences of dynamic shoulder instability.[19]

Clinical Significance

Scapulothoracic Articulation

The scapulothoracic articulation is an intricate, sliding junction that composes part of the shoulder in conjunction with the glenohumeral, acromioclavicular and coracoclavicular joints. The scapula has a complex anatomical relationship, comprised of 17 muscular attachments that function to dynamically stabilize the scapula and control the position of the glenoid to permit a wide range of motion for the upper extremity through the glenohumeral joint. The scapula does not have any ligamentous connections to the thorax. Due to the complexity of the scapulothoracic articulation, scapulothoracic disorders can be present and go underdiagnosed or underestimated because of the various and often subtle morphological alterations in normal architecture.[6]

Levator Scapulae Syndrome

The most common clinical manifestation of levator scapulae pathology is levator scapulae syndrome or tenderness over the upper medial angle of the scapula. Though well documented, this condition is often unrecognized. Movements that stretch the muscle tend to exaggerate symptoms. There is a hypothesis that constant trigger points, crepitation, and increased heat emission result from a combination of anatomic variability and the confluence of a bursa between the insertion of the levator scapulae, origin serratus anterior, and the scapula. Effective treatment modalities include physical therapy and/or local corticosteroid injections.[16][20]

Snapping Scapula Syndrome

Significant shoulder dysfunction can present as painful crepitus or scapulothoracic bursitis, termed snapping scapula syndrome or "washboard syndrome." This condition commonly manifests secondary to a chronic injury, overuse, or muscle imbalance that impacts the scapulothoracic articulation. Osseous lesions at the superomedial angle of the scapula secondary to repetitive injury or avulsion of the levator scapulae have also been implicated in the clinical manifestation.[6][21] This condition may be more common in military personnel due to chronic stress and recurrent injury secondary to load-bearing activities of the upper extremity. Treatment is typically conservative, with an 80% success rate.[22] For those that fail conservative treatment, arthroscopic bursectomy with or without partial scapulectomy is the most effective treatment modality.[23][24]

Myofascial Pain

Cervical myofascial pain is a musculoskeletal disorder consisting of pain attributed to muscles and their surrounding fascia. The levator scapulae are one of the most commonly involved muscles in the cervical spine. The etiology of myofascial pain is not completely understood but commonly results from postural mechanics, muscle overuse, trauma, or secondarily to another pathologic condition, such as fibromyalgia or arthropathies of zygapophyseal joints.[25][26] Cervical myofascial pain can be local, regional, or characterized by trigger points. Trigger points are hypersensitive areas in muscle tissue that elicit pain with mechanical stimulation and can refer pain to surrounding tissue. The levator scapulae is a common location for trigger points and frequently has a tender point associated with the diagnosis of fibromyalgia.[27][28][29]

Other Clinical Considerations

There are also documented cases of active trigger points of the levator scapula with a high prevalence, including those secondary to an acute whiplash injury.[30] Pain at the insertion site correlates with upper and median cervical spine dysfunction.[31] Varying degrees of levator scapulae atrophy are observable in patients with Sprengel deformity.[32]

Other Issues

Association with Posterior Triangle of the Neck

The posterior triangle of the neck, located in the lateral cervical region, is an important anatomic location for surgeons and anesthesiologists. The contents of this anatomic region include the entire brachial plexus, cervical sympathetic ganglions, deep cervical lymph nodes, and the major vascular structures of the neck/upper extremity. Other nerves, such as the spinal accessory, phrenic, vagus, and cutaneous cervical nerves, course through the region. The posterior triangle of the neck forms from the sternocleidomastoid anteriorly, trapezius posteriorly, and clavicle as the base. The levator scapulae form part of the floor along with the splenius, scalenus, and anterior scalene muscles.

The location of the levator scapulae in the posterior triangle of the neck is pivotal when performing a cervical paravertebral block of the brachial or cervical plexuses utilizing a posterior approach. In the posterior approach to the brachial or cervical plexuses, a muscle-sparing needle trajectory is optimal to decrease pain and soft tissue injury associated with the procedure. The needle insertion can be between the levator scapula and trapezius muscles.[5][33]

Medial Angle

The angle at the medial border, or spinovertebral angle, represents the insertion site of the levator scapulae. Research has noted that the right spinovertebral angle is greater than the left, and alteration of the angle may result in levator scapulae pathology from a directional change of the insertion site, possibly manifesting as neck stiffness.[3]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

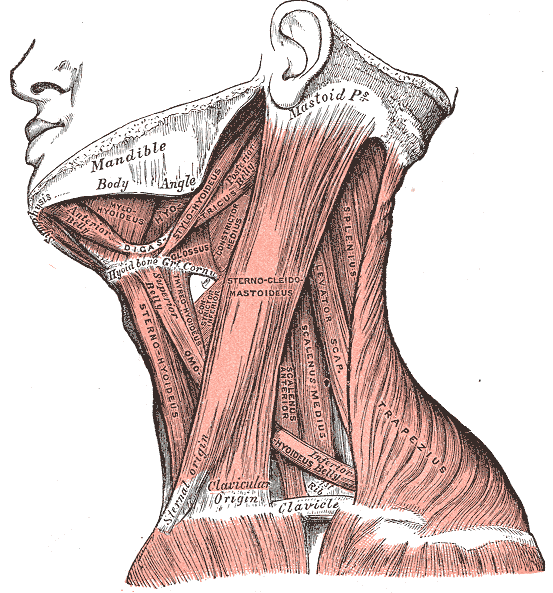

Neck Muscles. This lateral-view illustration shows the trapezius, sternocleidomastoideus, sternohyoideus, omohyoideus belly, scalenus anterior and medius, levator scapulae, splenius, mylohyoideus, thyrohyoideus, digastricus, and stylohyoideus muscles. The mandible, mastoid process, clavicle, and hyoid bone are also shown.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

(Click Image to Enlarge)

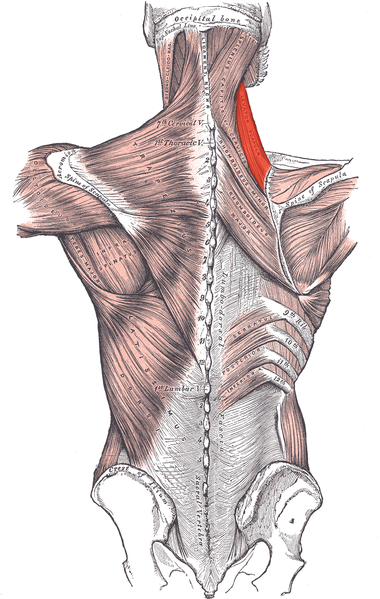

Muscles connecting the upper extremity to the vertebral column, Occipital Bone, Superior Nuchal Line, Sternocleidomastoid, Ligamentum Nuchae, Splenius Capitis of Cervicis, Levator Scapula (highlighted), Rhomboideus Minor and Major, Spine of Scapula, Trapezius, Deltoideus, Teres Major, Infraspinatus, Latissimus Dorsi, Serratus Posterior Inferior, Lumbar Triangle, Cres of Ilium, Sacral Vertebrae.

Henry Vandyke Carter, Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

References

Anderson WS, Lawson HC, Belzberg AJ, Lenz FA. Selective denervation of the levator scapulae muscle: an amendment to the Bertrand procedure for the treatment of spasmodic torticollis. Journal of neurosurgery. 2008 Apr:108(4):757-63. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/4/0757. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18377256]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMitchell B, Imonugo O, Tripp JE. Anatomy, Back, Extrinsic Muscles. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 30725901]

Oladipo GS, Aigbogun EO Jr, Akani GL. Angle at the Medial Border: The Spinovertebra Angle and Its Significance. Anatomy research international. 2015:2015():986029. doi: 10.1155/2015/986029. Epub 2015 Oct 7 [PubMed PMID: 26523233]

Vetter M,Charran O,Yilmaz E,Edwards B,Muhleman MA,Oskouian RJ,Tubbs RS,Loukas M, Winged Scapula: A Comprehensive Review of Surgical Treatment. Cureus. 2017 Dec 7; [PubMed PMID: 29456903]

Ihnatsenka B, Boezaart AP. Applied sonoanatomy of the posterior triangle of the neck. International journal of shoulder surgery. 2010 Jul:4(3):63-74. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.76963. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21472066]

Frank RM, Ramirez J, Chalmers PN, McCormick FM, Romeo AA. Scapulothoracic anatomy and snapping scapula syndrome. Anatomy research international. 2013:2013():635628. doi: 10.1155/2013/635628. Epub 2013 Nov 28 [PubMed PMID: 24369502]

Cowan PT,Varacallo M, Anatomy, Back, Scapula 2019 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 30285370]

Eliot DJ, Electromyography of levator scapulae: new findings allow tests of a head stabilization model. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 1996 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 8903697]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBishop KN, Varacallo M. Anatomy, Shoulder and Upper Limb, Dorsal Scapular Nerve. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29083775]

Goto H,Kimmey SC,Row RH,Matus DQ,Martin BL, FGF and canonical Wnt signaling cooperate to induce paraxial mesoderm from tailbud neuromesodermal progenitors through regulation of a two-step epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Development (Cambridge, England). 2017 Apr 15; [PubMed PMID: 28242612]

Kohli S,Yadav N,Prasad A,Banerjee SS, Anatomic variation of subclavian artery visualized on ultrasound-guided supraclavicular brachial plexus block. Case reports in medicine. 2014; [PubMed PMID: 25143765]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceVerenna AA,Alexandru D,Karimi A,Brown JM,Bove GM,Daly FJ,Pastore AM,Pearson HE,Barbe MF, Dorsal Scapular Artery Variations and Relationship to the Brachial Plexus, and a Related Thoracic Outlet Syndrome Case. Journal of brachial plexus and peripheral nerve injury. 2016; [PubMed PMID: 28077957]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceReiner A,Kasser R, Relative frequency of a subclavian vs. a transverse cervical origin for the dorsal scapular artery in humans. The Anatomical record. 1996 Feb; [PubMed PMID: 8808401]

Muir B. Dorsal scapular nerve neuropathy: a narrative review of the literature. The Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. 2017 Aug:61(2):128-144 [PubMed PMID: 28928496]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceChotai PN,Loukas M,Tubbs RS, Unusual origin of the levator scapulae muscle from mastoid process. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2015 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 26074045]

Menachem A, Kaplan O, Dekel S. Levator scapulae syndrome: an anatomic-clinical study. Bulletin (Hospital for Joint Diseases (New York, N.Y.)). 1993 Spring:53(1):21-4 [PubMed PMID: 8374486]

Loukas M,Louis RG Jr,Merbs W, A case of atypical insertion of the levator scapulae. Folia morphologica. 2006 Aug; [PubMed PMID: 16988922]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGalano GJ,Bigliani LU,Ahmad CS,Levine WN, Surgical treatment of winged scapula. Clinical orthopaedics and related research. 2008 Mar; [PubMed PMID: 18196359]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceNguyen H, Nguyen HV. [The 2 key muscles in thoracotomy for excision of the lung. The latissimus dorsi and the levator scapulae muscles]. Journal de chirurgie. 1986 Nov:123(11):626-34 [PubMed PMID: 3611219]

Estwanik JJ, Levator Scapulae Syndrome. The Physician and sportsmedicine. 1989 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 27448128]

de Carvalho SC,Castro ADAE,Rodrigues JC,Cerqueira WS,Santos DDCB,Rosemberg LA, Snapping scapula syndrome: pictorial essay. Radiologia brasileira. 2019 Jul-Aug; [PubMed PMID: 31435089]

Patzkowski JC, Owens BD, Burns TC. Snapping scapula syndrome in the military. Clinics in sports medicine. 2014 Oct:33(4):757-66. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2014.06.003. Epub 2014 Aug 27 [PubMed PMID: 25280621]

Warth RJ, Spiegl UJ, Millett PJ. Scapulothoracic bursitis and snapping scapula syndrome: a critical review of current evidence. The American journal of sports medicine. 2015 Jan:43(1):236-45. doi: 10.1177/0363546514526373. Epub 2014 Mar 24 [PubMed PMID: 24664139]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMerolla G, Cerciello S, Paladini P, Porcellini G. Snapping scapula syndrome: current concepts review in conservative and surgical treatment. Muscles, ligaments and tendons journal. 2013 Apr:3(2):80-90. doi: 10.11138/mltj/2013.3.2.080. Epub 2013 Jul 9 [PubMed PMID: 23888290]

Duyur Cakit B, Genç H, Altuntaş V, Erdem HR. Disability and related factors in patients with chronic cervical myofascial pain. Clinical rheumatology. 2009 Jun:28(6):647-54. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1116-0. Epub 2009 Feb 18 [PubMed PMID: 19224128]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMoney S, Pathophysiology of Trigger Points in Myofascial Pain Syndrome. Journal of pain [PubMed PMID: 28379050]

Touma J, May T, Isaacson AC. Cervical Myofascial Pain. StatPearls. 2023 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29939602]

Alonso-Blanco C, Fernández-de-las-Peñas C, Morales-Cabezas M, Zarco-Moreno P, Ge HY, Florez-García M. Multiple active myofascial trigger points reproduce the overall spontaneous pain pattern in women with fibromyalgia and are related to widespread mechanical hypersensitivity. The Clinical journal of pain. 2011 Jun:27(5):405-13. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318210110a. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21368661]

Tornero-Caballero MC,Salom-Moreno J,Cigarán-Méndez M,Morales-Cabezas M,Madeleine P,Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Muscle Trigger Points and Pressure Pain Sensitivity Maps of the Feet in Women with Fibromyalgia Syndrome. Pain medicine (Malden, Mass.). 2016 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 27257287]

Fernández-Pérez AM,Villaverde-Gutiérrez C,Mora-Sánchez A,Alonso-Blanco C,Sterling M,Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Muscle trigger points, pressure pain threshold, and cervical range of motion in patients with high level of disability related to acute whiplash injury. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2012 Jul; [PubMed PMID: 22677576]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMaigne JY, Chantelot F, Chatellier G. Interexaminer agreement of clinical examination of the neck in manual medicine. Annals of physical and rehabilitation medicine. 2009 Feb:52(1):41-8. doi: 10.1016/j.rehab.2008.11.001. Epub 2009 Jan 22 [PubMed PMID: 19419657]

Kadavkolan AS,Bhatia DN,Dasgupta B,Bhosale PB, Sprengel's deformity of the shoulder: Current perspectives in management. International journal of shoulder surgery. 2011 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 21660191]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCasale J,Geiger Z, Anatomy, Head and Neck, Posterior Neck Triangle 2019 Jan; [PubMed PMID: 30725974]