Introduction

Inferior vena cava (IVC) thrombosis is a disease associated with high morbidity. Although the condition is considered rare, case reports have shown that IVC thromboses may be underdiagnosed. For example, most commonly, pulmonary emboli are thought to arise from a lower extremity deep venous thrombosis. However, there are cases where an IVC thrombus caused the discovered pulmonary embolism. IVC thrombosis should be part of the differential diagnosis for a patient with a risk for a thromboembolic event. The predisposing prothrombotic condition should be determined once an IVC thrombus is identified, as there are many potential causes.[1][2][3]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Virchow’s triad can explain the pathophysiology leading to IVC thrombosis. This triad has three components: stasis in blood flow, endothelial injury, and hypercoagulability. There are two main subgroups used to describe the causes of IVC thrombosis:

- IVC Thrombosis in Congenitally Normal Inferior Vena Cava

When the IVC is developmentally normal, thrombosis formation most commonly occurs from compression from adjacent structures. Examples of compressive structures can include renal cell tumors, pancreatic carcinoma, large uterine fibroid, Budd-Chiari Syndrome, liver abscess, retroperitoneal masses, abdominal aortic aneurysm, and others. These are all examples in which the IVC has normal function, and external structures are causing compressive forces that result in stasis of blood flow. Additionally, certain populations of patients are predisposed to develop thrombi because of a hypercoagulable state. Examples include thrombophilia or factor V Leiden mutation. Modifiable factors such as oral contraceptives, smoking, obesity, pregnancy, and hormonal replacement therapy also place patients at increased risk for the development of a thrombus. A significant cause of IVC thrombosis is occlusion of an IVC filter which is becoming more prevalent due to the increased placement of these devices. Trauma is also a cause of inferior vena cava thrombosis. The injury can occur during percutaneous cannulation of the femoral vein or during cardiopulmonary bypass. Insertion of dialysis catheters, femoral venous catheters, pacemaker wires, and vena cava filters are all potential causes of inferior vena cava thrombosis.

- IVC Thrombosis in Congenitally Abnormal Inferior Vena Cava

A congenitally abnormal IVC leads to turbulent blood flow, which can ultimately lead to the development of a thrombus. Congenital IVC anomalies occur in approximately 1% of the population, and within that 1%, about 60 to 80% develop IVC thrombosis. The location of the thrombus depends on the congenital abnormality, which can range from infrarenal to suprarenal. Examples include a duplicate inferior vena cava, absence of infrarenal IVC, and even an accessory left renal vein leading to thrombus formation.[4][5]

Epidemiology

The exact incidence of IVC thrombosis is difficult to measure due to the wide-ranging presentations that can occur with IVC thrombosis. For those patients diagnosed with deep venous thrombosis, there is a reported incidence of 4-15% of associated IVC thrombosis. However, the true incidence may be under-represented due to the variability in clinical presentation. Patients diagnosed with pulmonary emboli may ultimately have an inferior vena cava thrombus, but if it is not suspected, there will not be appropriate diagnostic imaging leading to the identification of the thrombus.

History and Physical

Clinical presentation can vary depending on the extent and location of the thrombus within the IVC. Typically, patients complain of leg heaviness, pain, swelling, and cramping. Symptoms can also be nonspecific, such as abdominal, flank, or back pain. Men may present with scrotal swelling. The vague nature of symptoms may delay diagnosis until clot migration to the lungs and renal veins occur, which leads to shortness of breath and oliguria, respectively. The presence of bilateral lower extremity edema and dilated superficial abdominal veins suggests the possibility of an IVC thrombus. Overall, given the ambiguous presentation, there are no pathognomonic history and physical exam findings to diagnose IVC thrombosis consistently across all patients.[6]

Evaluation

There are currently no societal guidelines available to aid in the diagnosis and management of IVC thrombosis. Multiple imaging modalities are potentially useful when IVC thrombosis is suspected. These include ultrasound, CT, MRI, and catheter venography.

IVC duplex ultrasound can be used to visualize a potential thrombus, but there are limitations to this modality. Overlying bowel gas and patient obesity may make visualization very difficult. Ultrasound should still be a consideration as an initial test, given the low-risk profile. Case studies have reported IVC thrombosis identification using ultrasound in the emergency department. Sonographic signs that indicate a potential thrombus include a monophasic waveform by doppler, a choppy sign indicating increased blood velocity, and an inability to compress the vessel.

Computer tomography (CT) can also be used to visualize the location of the thrombus. However, MRI is the most reliable technique for visualizing the presence and extent of the thrombus. Given the poor general availability and the high cost of MRI, it should not be the initial imaging choice. Direct catheter venography is the most common imaging technique to arrive at a definitive diagnosis.

Once the thrombus is diagnosed, there should be a consideration for imaging dedicated to potential complications from the IVC thrombus. Approximately 12% of patients diagnosed with an IVC thrombus will develop pulmonary emboli. Therefore, a dedicated CT angiogram of the thorax may be needed to evaluate for pulmonary emboli. If there is a concern for renal involvement, nuclear renal scanning can be used to assess for renal vascular compromise.

Treatment / Management

Initial management consists of anticoagulation. Heparin can be started in the emergency department with the goal of bridging to warfarin or a newer generation anticoagulant. Additional treatment options depend on the acuity of the thrombus. There may be a benefit to catheter-directed thrombolysis or thrombectomy if the IVC thrombus is acute (<14 days), subacute (15 to 28 days), and for a patient who is not at high risk of bleeding. Percutaneous transluminal angioplasty with stenting is also a consideration. However, chronic (more than 28 days) IVC thrombosis may benefit more from stenting than catheter-directed thrombolysis. Ultimately, when evaluating the patient in the emergency department, starting heparin is crucial. Consulting vascular surgery is necessary for other potential treatment options. If the IVC thrombus is due to an extrinsic cause, such as a tumor, then further diagnostic testing will be needed.[3][7](B2)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnosis possibilities for a patient with suspected IVC thrombosis are broad. The differential diagnosis may include nephrolithiasis, renal cell carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, DVT, liver disease, spinal pathology, pulmonary emboli, bowel obstruction, and urinary retention.

Prognosis

The overall prognosis hinges on the underlying cause of the thrombus. If a patient has a hereditary hypercoagulable disease, they are predisposed to the development of thrombi. However, if they are compliant with their anticoagulation therapy, their prognosis will be favorable. Alternatively, if the patient is diagnosed with progressive cancer, such as pancreatic cancer, that has extended and compressed the IVC, their prognosis is likely poor.

Children who have had catheterization have gone on to develop unilateral leg swelling and chronic pain. Finally, there is the potential of pulmonary embolus if the inferior vena cava has a floating embolus.

Complications

If untreated, patients can suffer from post-thrombotic syndrome, which consists of venous stasis changes leading to ulceration in the lower extremities. Other complications include pulmonary emboli and renal ischemia due to the extension of the thrombus. Thus, if IVC thrombosis is a consideration, imaging should not be delayed.

Deterrence and Patient Education

The most important factor in determining patient education would be targeting patients who have modifiable risk factors. Patients who are at increased risk of thrombus formation are those who are obese, use oral contraceptive pills and have a smoking history. Education and prevention of these modifiable risk factors will make the most significant difference. For those patients who have a hereditary disorder such as Factor V Leiden, the importance of long-term anticoagulation must be discussed to prevent thrombus formation.

Pearls and Other Issues

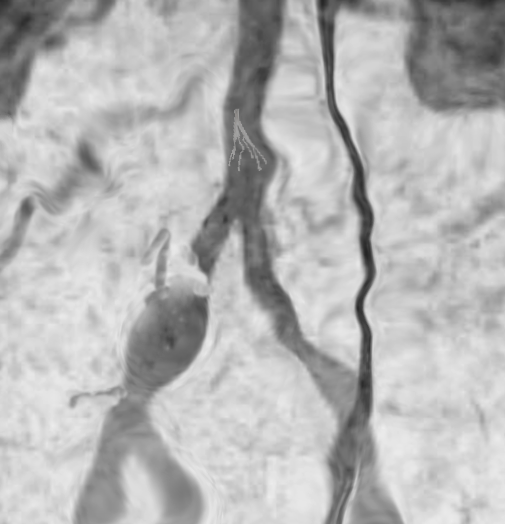

The image shows an IVC filter in a patient with a common iliac vein injury from the use of a trocar during lap cholecystectomy. The right common iliac vein had to be ligated, and an IVC filter was placed via the RIJ. A crossover saphenous vein graft bypass is planned to help decompress the right leg.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

Interprofessional communication is the key to success in patient care. Most medical errors that occur are secondary to a lack of communication. All team members must be at liberty to speak up when they have concerns. For IVC thrombosis, coordination of care by physicians is necessary. An emergency medicine physician may initially evaluate the patient, but they must be able to contact the vascular surgery, nephrologist, etc., for further management. In addition to communication skills is the importance of knowing one's limits. There must be a willingness to ask for help when needed to improve healthcare outcomes. Excellent communication and awareness of personal limitations among all team members are critical.

Media

References

Shi W,Dowell JD, Etiology and treatment of acute inferior vena cava thrombosis. Thrombosis research. 2017 Jan [PubMed PMID: 27865097]

Alkhouli M,Morad M,Narins CR,Raza F,Bashir R, Inferior Vena Cava Thrombosis. JACC. Cardiovascular interventions. 2016 Apr 11 [PubMed PMID: 26952909]

Qureshi I, Inferior vena cava thrombosis. BMJ case reports. 2013 Apr 23 [PubMed PMID: 23616335]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGolowa Y,Warhit M,Matsunaga F,Cynamon J, Catheter directed interventions for inferior vena cava thrombosis. Cardiovascular diagnosis and therapy. 2016 Dec [PubMed PMID: 28123981]

Andreoli JM,Thornburg BG,Hickey RM, Inferior Vena Cava Filter-Related Thrombus/Deep Vein Thrombosis: Data and Management. Seminars in interventional radiology. 2016 Jun [PubMed PMID: 27247478]

Kraft C,Hecking C,Schwonberg J,Schindewolf M,Lindhoff-Last E,Linnemann B, Patients with inferior vena cava thrombosis frequently present with lower back pain and bilateral lower-extremity deep vein thrombosis. VASA. Zeitschrift fur Gefasskrankheiten. 2013 Jul [PubMed PMID: 23823859]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYe K,Qin J,Yin M,Liu X,Lu X, Outcomes of Pharmacomechanical Catheter-directed Thrombolysis for Acute and Subacute Inferior Vena Cava Thrombosis: A Retrospective Evaluation in a Single Institution. European journal of vascular and endovascular surgery : the official journal of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. 2017 Oct [PubMed PMID: 28801136]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidence