Anatomy, Head and Neck, Ear Internal Auditory Canal (Internal Auditory Meatus, Internal Acoustic Canal)

Anatomy, Head and Neck, Ear Internal Auditory Canal (Internal Auditory Meatus, Internal Acoustic Canal)

Introduction

The internal auditory canal (IAC), also referred to as the internal acoustic meatus lies in the temporal bone and exists between the inner ear and posterior cranial fossa. It includes the vestibulocochlear nerve (CN VIII), facial nerve (CN VII), the labyrinthine artery, and the vestibular ganglion. Knowledge of the anatomy and relationship of these structures plays a vital role during the evaluation and management of diseases involving the internal auditory canal.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The internal auditory canal begins in the temporal bone within the cranial cavity at an oval-shaped opening called the porus acusticus internus. The canal runs through the petrous segment of the temporal bone, which is located between the inner ear and posterior cranial fossa. It is lined by dura and filled with spinal fluid. The rounded and smooth canal is on average 8.5mm (5.5 to 10.mm) in length and about 4mm in diameter.[1]

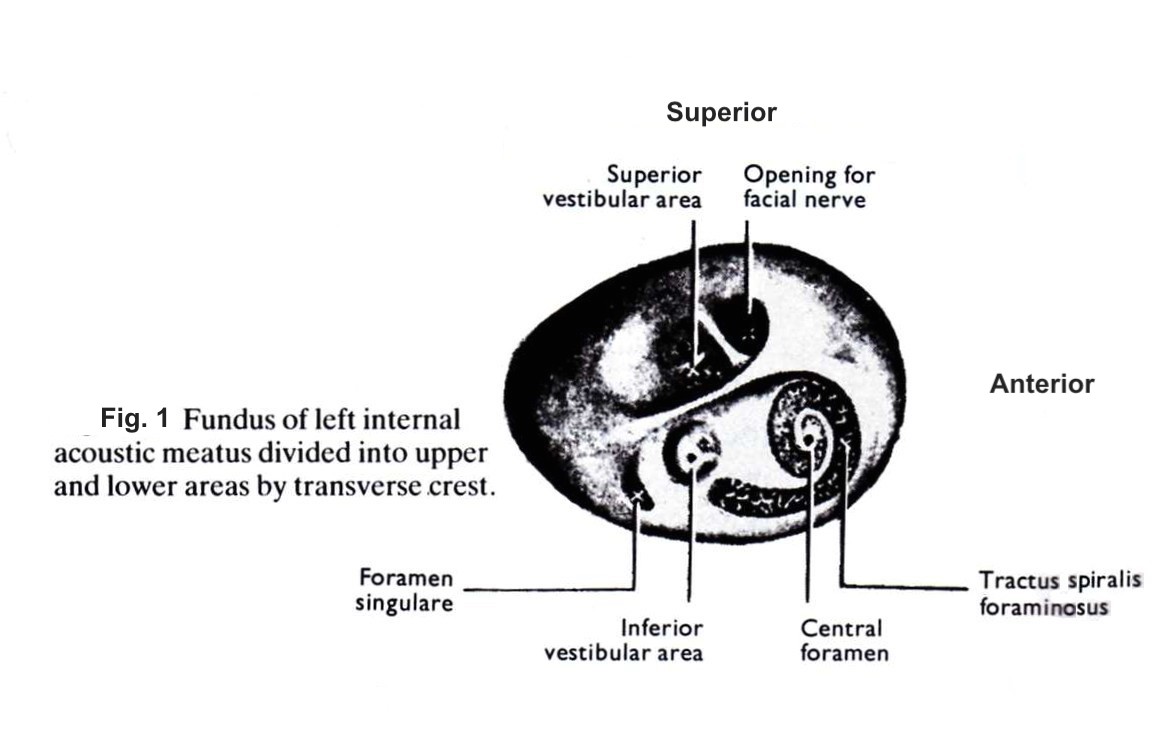

The canal narrows as it moves towards the fundus, a thin cribriform plate of bone that marks the lateral boundary of the canal. The fundus separates the internal auditory canal from the cochlea and vestibule which are located in close proximity.[2] It is divided into superior and inferior segments by the transverse crest (also called the falciform crest). The superior half is further divided into anterior and inferior segments by Bill’s bar, a vertical crest of bone named after otologist Dr. William House. These two spines form three distinct osseous structures through which the facial and vestibulocochlear nerve branches can be found in a consistent pattern, represented by figure 1. The posterior portion of the fundus is filled with a macula crista, which is a series of very small openings that the vestibular nerves pass to reach the superior and inferior semicircular canals.

The vestibulocochlear nerve runs most often posteriorly to the facial nerve in the internal auditory canal. In the lateral segment of the internal auditory canal, about 3 to -4mm from the fundus, the cochlear and vestibular nerves join to form one common nerve. The vestibular portion is further segmented into the superior and inferior portions at the fundus.[3] The superior portion of the vestibular nerve innervates three structures- the superior and lateral semicircular canals, and the utricle. The inferior portion innervates the remaining vestibular structures- the posterior semicircular canal and the saccule. The afferent projections from both the superior and inferior vestibular nerves join in the IAC at the vestibular ganglion, often called the Scarpa ganglion. Interestingly, the vestibular ganglion is one of the first ganglions to reach full mature size, as early as the first week of postnatal life.[4]

The singular canal is a significant landmark during surgery of the internal auditory canal and labyrinth. It carries the posterior ampullary nerves (PAN) and enters the internal auditory canal in the posteroinferior aspect near the fundus.[5] The PAN innervates the ampulla of the posterior semicircular canal and joins the saccular nerve within the internal auditory canal to form the inferior vestibular nerve.

The facial nerve is found most often in the anterosuperior quadrant of the internal auditory canal. The facial nerve exits the internal auditory canal at the meatal foramen and continues towards the geniculate ganglion as the labyrinthine segment. The nervus intermedius is a branch of the facial nerve located posteriorly to the facial nerve and anterior to the superior vestibular nerve in the internal auditory canal.[6] It carries the sensory and parasympathetic fibers of the facial nerve and joins the main motor root of the facial nerve at the geniculate ganglion.

Embryology

Much of the structures in the ear develop very early in gestation. The internal auditory canal develops in the petrous portion of the temporal bone in the posterior fossa. The internal auditory canal continues to lengthen as the cranium increases up until about age ten, whereas the diameter of the medial opening to the canal increases only slightly in the first year of life.[7]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The entire inner ear receives vascular supply from the labyrinthine artery (LA), also called the internal auditory artery, which is most often a branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) but can also branch from the basilar artery in a minority of cases.[8] The LA enters the IAC medially in the anteroinferior portion of the porus acusticus internus and courses between the cochlear and facial nerve. It divides into its two terminal main branches at the fundus, the anterior vestibular artery, and the common cochlear artery.

Clinical Significance

Appreciating the complexity and important anatomical relationships of the structures in the internal auditory canal is vital for both surgeons and clinicians when evaluating pathologies of the inner ear. Knowledge of anatomy helps physicians identify involved structures on imaging and aids in identifying landmarks to prevent iatrogenic injury during operations. The structures within the internal auditory canal have been implicated in pathology arising from tumors, vascular events, vestibular, and auditory structures.

Vestibular schwannomas, or acoustic neuromas, are the most common tumor affecting the internal auditory canal. Over 90% of schwannomas arise from the vestibular nerves within the internal auditory canal, with the majority involving the inferior vestibular nerve.[9] While not malignant, schwannomas can cause serious morbidity due to the close association with various nerves in the internal auditory canal and potential expansion into the cerebellopontine angle. Identifying which structures in and around the internal auditory canal are involved is vital in determining the approach and minimizing complications during surgery.[10]

The knowledge of vascular anatomy plays an important role in the diagnosis and management of certain inner ear conditions. Since the labyrinth has no collateral blood flow, it is especially vulnerable to ischemic events, with even a 15-second cessation of blood flow having been shown to cause decreased auditory nerve excitability.[11][12] Clinically, this will present with acute onset of vestibular symptoms such as vertigo, imbalance, and nausea, as well as tinnitus or hearing loss.

Microvascular compression of the nerves in the internal auditory canal can cause severe tinnitus, vertigo, and hemifacial spasm from the involvement of the facial nerve. Vascular loop syndrome results from a prominent loop of the AICA that enters the internal auditory canal and causes compression of the nerves within. While the exact pathology of compression by vascular loops is a topic of debate, some groups believe that pulsatile tinnitus has correlations with vascular loops in the internal auditory canal.[13][14] Often, these patients present with compressive symptoms very similar to the presentation with a neoplasm, such as acoustic neuromas. Microvascular decompression is a surgical procedure that physically separates the vessel from the nerves, and a variety of reports have demonstrated significant symptomatic improvement after the procedure when the compression is truly significant.[15][16][17]

Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is first treated conservatively with positional maneuvers with resolution seen in the vast majority of patients. However, a minority can develop disabling chronic BPPV. Since the BPPV is most commonly caused by pathology in the posterior semicircular canal, selective singular neurectomy has been shown to relieve positional vertigo in 95% of patients with BPPV refractory to more conservative measures.[18][19] Knowledge of the anatomy of the singular nerve and its relationship with the structures within the internal auditory canal is vital to successful procedures as well as minimizing complications. It merits noting that while this procedure remains effective, it has been largely replaced by posterior semicircular canal plugging in patients who fail to respond to conservative measures.

A vestibular nerve section is a surgical option for patients who have vertigo refractory to medical treatment for diseases such as Meniere disease and vestibular neuritis. Episodic vestibular symptoms characterize Meniere disease. Vestibular neuritis is one of the most common causes of acute spontaneous vertigo and tends to occur from herpes simplex virus reactivation in the vestibular ganglion.[20] A vestibular nerve section has the advantage of addressing vertigo in these diseases while preserving hearing. A plane between the vestibular and cochlear nerves is identified within the internal auditory canal to sever the vestibular nerve safely. If no plane can be found, the surgeon can cut the superior section of the vestibulocochlear nerve with substantially equal outcomes.[21] However, much like the singular neurectomy, this procedure has become far less common in the last decade as it has been replaced in large part by less invasive transtympanic procedures.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Fatterpekar GM, Mukherji SK, Lin Y, Alley JG, Stone JA, Castillo M. Normal canals at the fundus of the internal auditory canal: CT evaluation. Journal of computer assisted tomography. 1999 Sep-Oct:23(5):776-80 [PubMed PMID: 10524866]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceKozerska M,Skrzat J, Anatomy of the fundus of the internal acoustic meatus - micro-computed tomography study. Folia morphologica. 2015; [PubMed PMID: 26339817]

Rubinstein D,Sandberg EJ,Cajade-Law AG, Anatomy of the facial and vestibulocochlear nerves in the internal auditory canal. AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 1996 Jun-Jul; [PubMed PMID: 8791922]

Anniko M. Formation and maturation of the vestibular ganglion. ORL; journal for oto-rhino-laryngology and its related specialties. 1985:47(2):57-65 [PubMed PMID: 3982811]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSilverstein H, Norrell H, Smouha E, Haberkamp T. The singular canal: a valuable landmark in surgery of the internal auditory canal. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 1988 Feb:98(2):138-43 [PubMed PMID: 3128756]

Rhoton AL Jr, Kobayashi S, Hollinshead WH. Nervus intermedius. Journal of neurosurgery. 1968 Dec:29(6):609-18 [PubMed PMID: 5708034]

Sakashita T,Sando I, Postnatal development of the internal auditory canal studied by computer-aided three-dimensional reconstruction and measurement. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1995 Jun; [PubMed PMID: 7771721]

Haidara A, Peltier J, Zunon-Kipre Y, N'da HA, Drogba L, Gars DL. Microsurgical Anatomy of the Labyrinthine Artery and Clinical Relevance. Turkish neurosurgery. 2015:25(4):539-43. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.9136-13.0. Epub [PubMed PMID: 26242329]

Khrais T, Romano G, Sanna M. Nerve origin of vestibular schwannoma: a prospective study. The Journal of laryngology and otology. 2008 Feb:122(2):128-31 [PubMed PMID: 18039415]

Brackmann DE. Acoustic neuroma: surgical approaches and complications. Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 1991 Sep:20(5):674-9 [PubMed PMID: 1781654]

PERLMAN HB, KIMURA R, FERNANDEZ C. Experiments on temporary obstruction of the internal auditory artery. The Laryngoscope. 1959 Jun:69(6):591-613 [PubMed PMID: 13673604]

FERNANDEZ C. The effect of oxygen lack on cochlear potentials. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1955 Dec:64(4):1193-203 [PubMed PMID: 13283493]

Ramly NA, Roslenda AR, Suraya A, Asma A. Vascular loop in the cerebellopontine angle causing pulsatile tinnitus and headache: a case report. EXCLI journal. 2014:13():192-6 [PubMed PMID: 26417253]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGultekin S,Celik H,Akpek S,Oner Y,Gumus T,Tokgoz N, Vascular loops at the cerebellopontine angle: is there a correlation with tinnitus? AJNR. American journal of neuroradiology. 2008 Oct; [PubMed PMID: 18653684]

Okamura T, Kurokawa Y, Ikeda N, Abiko S, Ideguchi M, Watanabe K, Kido T. Microvascular decompression for cochlear symptoms. Journal of neurosurgery. 2000 Sep:93(3):421-6 [PubMed PMID: 10969939]

Brackmann DE, Kesser BW, Day JD. Microvascular decompression of the vestibulocochlear nerve for disabling positional vertigo: the House Ear Clinic experience. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2001 Nov:22(6):882-7 [PubMed PMID: 11698813]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRyu H,Uemura K,Yokoyama T,Nozue M, Indications and results of neurovascular decompression of the eighth cranial nerve for vertigo, tinnitus and hearing disturbances. Advances in oto-rhino-laryngology. 1988; [PubMed PMID: 3213742]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceGacek RR. Singular neurectomy update. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 1982 Sep-Oct:91(5 Pt 1):469-73 [PubMed PMID: 7137783]

Gacek RR, Gacek MR. Singular neurectomy in the management of paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 1994 Apr:27(2):363-79 [PubMed PMID: 8022615]

Jeong SH,Kim HJ,Kim JS, Vestibular neuritis. Seminars in neurology. 2013 Jul [PubMed PMID: 24057821]

Silverstein H, Jackson LE. Vestibular nerve section. Otolaryngologic clinics of North America. 2002 Jun:35(3):655-73 [PubMed PMID: 12486846]