Introduction

Brain metastases are a common complication of cancer and the most common type of brain tumor. Anywhere from 10% to 26% of patients who die from their cancer will develop brain metastases.[1] While few cancers that metastasize to the brain can be cured using conventional therapies, long-term survival and palliation are possible with minimal adverse effects to patients. Increasingly, neuro-cognition and quality of life are being recognized as important endpoints for patients as survival continues to increase.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

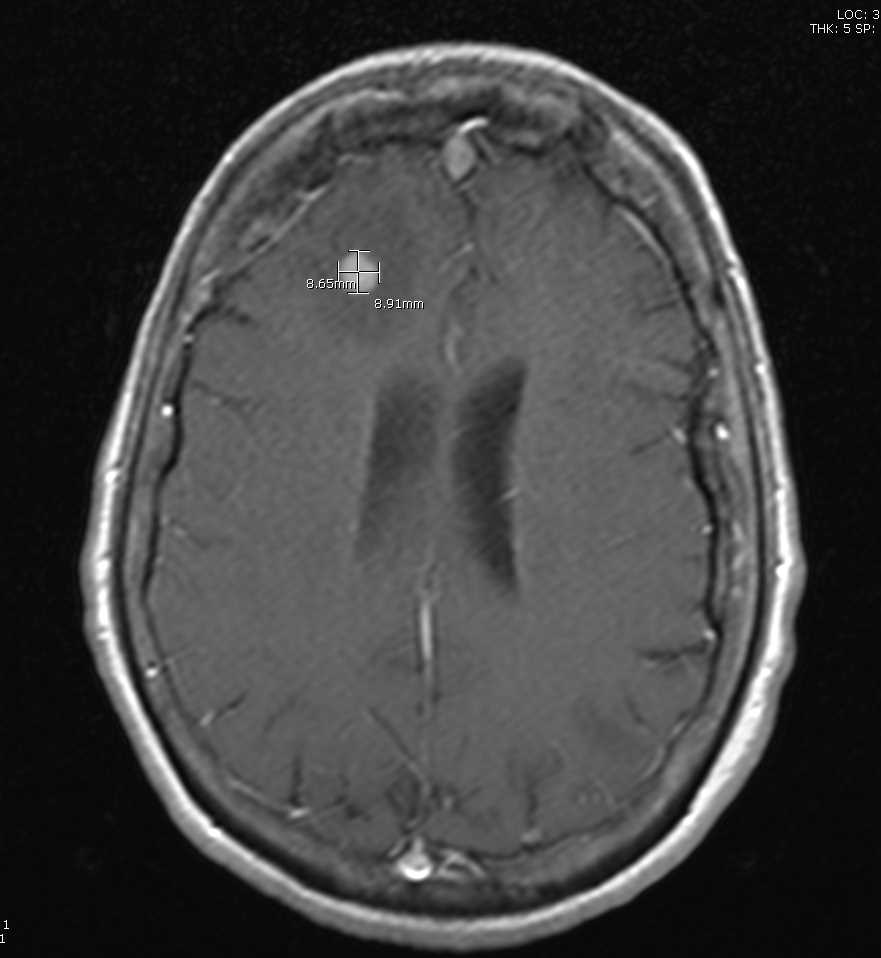

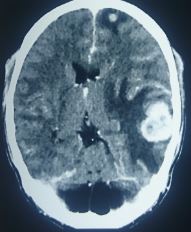

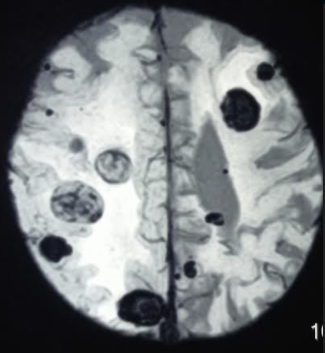

Primary cancers such as lung, breast, and melanoma are most likely to metastasize to the brain (see Images. T1-Weighted Postcontrast MRI Image Showing Lung Cancer, Metastasis From Melanoma). Small-cell lung cancer has a high propensity to spread to the brain such that prophylactic treatment (cranial irradiation) is considered the standard of care. Other malignancies such as prostate and head and neck cancers rarely result in brain metastases. It can be difficult to predict which patients will develop brain metastases other than by using tumor type and subtype.

Epidemiology

Brain metastases are the most common type of intracranial tumor. In the United States, an estimated 98,000 to 170,000 cases occur each year. The incidence of brain metastases is increasingly likely as a result of several factors.[2] Patients with a systemic metastatic disease have a longer survival with new systemic therapies (including immunotherapy) that have recently seen more widespread use. Furthermore, the growing use of sensitive magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques has contributed to the better detection of small asymptomatic brain metastases.

Pathophysiology

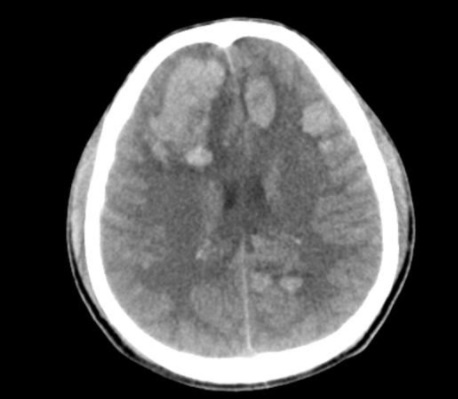

Metastatic cancer passes through the bloodstream and enters the central nervous system through a breakdown of the blood-brain barrier. Clonal cells then proliferate, causing local invasion, displacement, inflammation, and edema. Distribution throughout the central nervous system is more common in areas of high blood flow; however, different histological subtypes tend to have different distributions of location within the brain.[3] See Image. Metastasis From Leukemia.

History and Physical

A detailed history and physical should be performed, focusing on symptoms, duration, and intensity. Focused questions about headaches, blurry vision, and nausea should be asked. A complete neurologic examination should be performed. This examination should include an assessment of strength, sensation, coordination, reflexes, cerebellar function, proprioception, cranial nerve function, speech, thought, vision, and memory. An ophthalmic examination should be performed to evaluate for papilledema. Additional information including age, performance status, and status of systemic cancer burden should be gathered to understand the disease course and guide future therapeutic intervention.

Evaluation

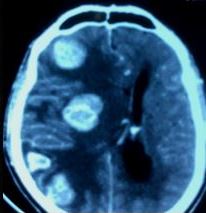

A head computed tomography (CT) allows for a quick examination. However, fine-slice MR of the brain with contrast is the gold standard for neuroimaging in cases of suspected brain metastases (see Image. Metastasis From Thyroid Cancer). MR allows for determining the number and anatomical location of tumors and the degree of associated edema (see Image. Multiple Hemorrhagic Metastases to the Brain). Basic laboratory assessment should be performed, including a complete blood count, metabolic panel, and liver function test.

Treatment / Management

The first step in the management of newly diagnosed brain metastases is the treatment of intracranial edema. Oral or intravenous steroids (such as dexamethasone) are commonly used. A loading dose of 10 mg intravenous (IV) dexamethasone followed by 4 mg IV every six hours is one dosing regimen. After the initial clinical response, which can occur rapidly, the dose may be tapered to avoid many of the adverse effects of long-term high dose steroid administration.

Following the initiation of steroids, definitive management may be initiated. Treatment options include surgical resection (for limited brain metastases in patients with good performance status and surgically accessible lesions), whole-brain radiotherapy, and stereotactic radiosurgery. Whole-brain radiotherapy is given by daily radiotherapy treatments (usual 10 to 15) targeting the whole brain. Radiosurgery is a more precise form of radiotherapy which delivers a large dose only to the area of the brain metastasis, usually in a single fraction. Each of these treatments has distinct advantages as well as a unique side effect profile. A multidisciplinary treatment team of a neurosurgeon, radiation oncologist, and neuro-oncologist should participate in the formulation of the treatment plan together with the patient.

The historical standard in patients with good performance status has been surgical resection. Local recurrence following surgical resection remains high, with one trial recently reporting 12-month freedom from local recurrence of 43% following surgical resection and observation.[4] Local control can be improved with post-operative radiosurgery or whole-brain radiotherapy.[4][5] Postoperative therapy should remain an individualized treatment recommendation, taking into account the number of non-resected metastases, tumor histology, follow-up, and patient preference. Whole-brain radiotherapy following surgical resection of brain metastases can increase intracranial control compared to postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery but results in poorer neuro-cognitive outcomes.[5](A1)

For patients either not eligible for surgical resection of brain metastases or who elect for non-surgical therapy, stereotactic radiosurgery offers an excellent option for controlling a limited number of intracranial metastases. Although first used in combination with whole-brain radiotherapy as a way to intensify local treatment, stereotactic radiosurgery is now commonly used as a stand-alone therapy. While ultimate control of brain metastases varies with dose and lesion size[6], lesions less than one centimeter have high local control with single-fraction radiosurgery.[7] For larger lesions, multi-fraction treatments are sometimes employed.[8] Stereotactic radiosurgery is considered standard for patients with one to four brain metastases, but emerging data indicate it may be an acceptable treatment for patients with up to ten brain metastases.[9](B2)

For patients with poor performance status or many brain metastases, the standard of care is whole-brain radiotherapy. Whole-brain radiotherapy provides control of individual brain metastases as well as reduces the risk of failure in the brain at a new site. These benefits must be weighed against its potential neurocognitive side effects which occur for many patients to a varying degree. Emerging data suggest that for patients with extremely poor performance status, whole-brain radiotherapy may have a minimal benefit over steroids alone.[10] Therefore, in the management of brain metastases, treatment decisions will need to be made on an individual patient level, taking into account the goals of treatment in a particular situation as well as the acceptable side effect profile.(A1)

Differential Diagnosis

The differential diagnoses of cerebral metastases include:

- Abscess

- Demyelination

- Parasitic infestation

- Primary tumor - glioma/ependymoma

Prognosis

The prognosis of cerebral metastasis depends on several factors including:

- Age of the patient

- Number and size of metastases

- Site of the primary tumor

- The other sites of metastases

- Presence of mass effect

- Radiosensitivity/chemosensitivity of the tumor

Complications

- Mass effect

- Brain herniation

- Seizures

- Hydrocephalus

- Spread to surrounding tissue

- Neurological deficit

- Death

Deterrence and Patient Education

The patient should be counseled regarding the diagnosis and prognosis. They should be instructed to adhere to the treatment plan and medications.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

The management of patients with brain metastases is best done with an interprofessional team that includes a neurosurgeon, an oncologist, neurologist, radiation therapist, palliative care specialist, pain consultant, anesthetist. Most of these patients are frail and have a reduced life expectancy; hence the need for aggressive measures is not warranted. A team approach should discuss the best approach taking into account patient status, comorbidity, and life span. Many of these patients simply benefit from palliation and pain control.[11][12]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Nayak L, Lee EQ, Wen PY. Epidemiology of brain metastases. Current oncology reports. 2012 Feb:14(1):48-54. doi: 10.1007/s11912-011-0203-y. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22012633]

Smedby KE, Brandt L, Bäcklund ML, Blomqvist P. Brain metastases admissions in Sweden between 1987 and 2006. British journal of cancer. 2009 Dec 1:101(11):1919-24. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605373. Epub 2009 Oct 13 [PubMed PMID: 19826419]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceQuattrocchi CC, Errante Y, Gaudino C, Mallio CA, Giona A, Santini D, Tonini G, Zobel BB. Spatial brain distribution of intra-axial metastatic lesions in breast and lung cancer patients. Journal of neuro-oncology. 2012 Oct:110(1):79-87. doi: 10.1007/s11060-012-0937-x. Epub 2012 Jul 18 [PubMed PMID: 22802020]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMahajan A, Ahmed S, McAleer MF, Weinberg JS, Li J, Brown P, Settle S, Prabhu SS, Lang FF, Levine N, McGovern S, Sulman E, McCutcheon IE, Azeem S, Cahill D, Tatsui C, Heimberger AB, Ferguson S, Ghia A, Demonte F, Raza S, Guha-Thakurta N, Yang J, Sawaya R, Hess KR, Rao G. Post-operative stereotactic radiosurgery versus observation for completely resected brain metastases: a single-centre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2017 Aug:18(8):1040-1048. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30414-X. Epub 2017 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 28687375]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceBrown PD, Ballman KV, Cerhan JH, Anderson SK, Carrero XW, Whitton AC, Greenspoon J, Parney IF, Laack NNI, Ashman JB, Bahary JP, Hadjipanayis CG, Urbanic JJ, Barker FG 2nd, Farace E, Khuntia D, Giannini C, Buckner JC, Galanis E, Roberge D. Postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery compared with whole brain radiotherapy for resected metastatic brain disease (NCCTG N107C/CEC·3): a multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. The Lancet. Oncology. 2017 Aug:18(8):1049-1060. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30441-2. Epub 2017 Jul 4 [PubMed PMID: 28687377]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceAmsbaugh MJ, Yusuf MB, Gaskins J, Dragun AE, Dunlap N, Guan T, Woo S. A Dose-Volume Response Model for Brain Metastases Treated With Frameless Single-Fraction Robotic Radiosurgery: Seeking to Better Predict Response to Treatment. Technology in cancer research & treatment. 2017 Jun:16(3):344-351. doi: 10.1177/1533034616685025. Epub 2016 Dec 27 [PubMed PMID: 28027696]

Chang EL, Hassenbusch SJ 3rd, Shiu AS, Lang FF, Allen PK, Sawaya R, Maor MH. The role of tumor size in the radiosurgical management of patients with ambiguous brain metastases. Neurosurgery. 2003 Aug:53(2):272-80; discussion 280-1 [PubMed PMID: 12925241]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMinniti G, Scaringi C, Paolini S, Lanzetta G, Romano A, Cicone F, Osti M, Enrici RM, Esposito V. Single-Fraction Versus Multifraction (3 × 9 Gy) Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Large (}2 cm) Brain Metastases: A Comparative Analysis of Local Control and Risk of Radiation-Induced Brain Necrosis. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2016 Jul 15:95(4):1142-8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2016.03.013. Epub 2016 Mar 19 [PubMed PMID: 27209508]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceYamamoto M, Serizawa T, Higuchi Y, Sato Y, Kawagishi J, Yamanaka K, Shuto T, Akabane A, Jokura H, Yomo S, Nagano O, Aoyama H. A Multi-institutional Prospective Observational Study of Stereotactic Radiosurgery for Patients With Multiple Brain Metastases (JLGK0901 Study Update): Irradiation-related Complications and Long-term Maintenance of Mini-Mental State Examination Scores. International journal of radiation oncology, biology, physics. 2017 Sep 1:99(1):31-40. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.04.037. Epub 2017 Aug 7 [PubMed PMID: 28816158]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMulvenna P, Nankivell M, Barton R, Faivre-Finn C, Wilson P, McColl E, Moore B, Brisbane I, Ardron D, Holt T, Morgan S, Lee C, Waite K, Bayman N, Pugh C, Sydes B, Stephens R, Parmar MK, Langley RE. Dexamethasone and supportive care with or without whole brain radiotherapy in treating patients with non-small cell lung cancer with brain metastases unsuitable for resection or stereotactic radiotherapy (QUARTZ): results from a phase 3, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet (London, England). 2016 Oct 22:388(10055):2004-2014. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30825-X. Epub 2016 Sep 4 [PubMed PMID: 27604504]

Level 1 (high-level) evidenceMatsuo S, Amano T, Kawauchi S, Nakamizo A. Multiple Brain Metastases from Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma Manifesting with Simultaneous Intratumoral Hemorrhages. World neurosurgery. 2019 Mar:123():221-225. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2018.12.036. Epub 2018 Dec 20 [PubMed PMID: 30579022]

Rastogi K, Bhaskar S, Gupta S, Jain S, Singh D, Kumar P. Palliation of Brain Metastases: Analysis of Prognostic Factors Affecting Overall Survival. Indian journal of palliative care. 2018 Jul-Sep:24(3):308-312. doi: 10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_1_18. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30111944]