Introduction

In 2010, over 16 million people in the US required treatment for dysphagia, either in the community or an inpatient setting. It is estimated that nearly 50% of hospitalized patients have a swallowing disorder, exposing them to the risk of aspiration pneumonia (with concomitant increased length of hospital stay), increased re-hospitalization, and increased mortality. By identifying at-risk patients early on, appropriate management can commence, helping reduce the risk of aspiration.[1]

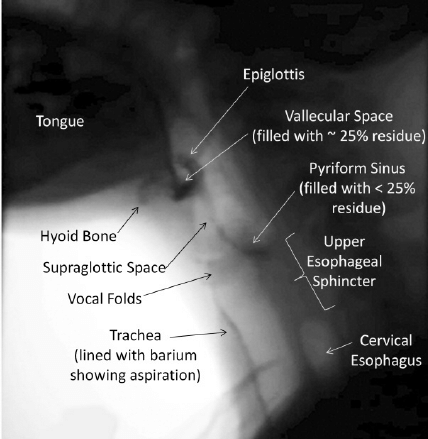

A holistic approach to nutritional needs can improve the patient’s overall quality of life and psychological health. In elderly patients, difficulties with swallowing can cause anxiety around a meal, and panic associated with this activity of daily living can result in the individual socially isolating themselves. These can all contribute to chronic malnutrition and inanition. A videofluoroscopic swallow study is considered the gold standard diagnostic tool for evaluating dysphagia (see Image. Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Study). It can assess dysphagia that may not be picked up by clinical examination or patient reporting. It can be combined with Functional Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing (FEES) to evaluate the swallowing mechanisms and mechanics comprehensively.[2][3][4]

Procedures

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Procedures

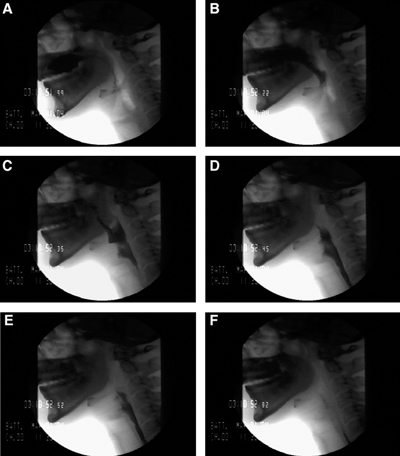

The patient is usually seated in the upright position on a chair or wheelchair for the duration of the examination to emulate the optimal physiological position for swallowing, with study views made in both the anterior-posterior and lateral views (see Image. Lateral Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Study). The field of study is from the oral cavity to the upper esophagus. Fluoroscopic images are recorded on the patient’s oral intake screen, allowing the healthcare professional to review the study retrospectively.

The clinician provides food and drinks of different consistencies to chew and swallow under fluoroscopy. The selection of test food is based on the swallowing difficulty being investigated. The speech and language therapist carefully selects the varying viscosities used to account for the potential severity of dysphagia posed by the subject, as well as any known anatomic or functional abnormalities. These test foods/liquids are pre-mixed with barium as the contrasting agent, though water-soluble contrast agents such as gastrograffin can also be utilized. With the radio-opaque bolus, images are obtained at different stages of the swallowing process to highlight and analyze the cause of dysphagia (see Image. Stages of the Swallowing Process).[5]

Indications

A videofluoroscopic swallow study is most often used to evaluate:

- Potential aspiration

- Oropharyngeal dysphagia

- Odynophagia or globus sensation

Evaluations for dysphagia or aspiration are often performed:

- Post cerebral infarct

- Patient with a history of neuromuscular disease

- Following head and neck surgery

- After radiation to the head or neck

There are few absolute contraindications. Suppose the patient is grossly aspirating on an exam. In that case, the exam can be performed quickly and carefully to gather limited information on why the aspiration is occurring and which structures are involved. However, this must always be balanced against the risk of large-volume aspiration of barium contrast medium, which can markedly impair respiratory function.

The patient must usually be able to sit or stand, and the exam is rarely performed in a supine position. The patient must be coherent and able to follow instructions to participate in the examination.[6]

Potential Diagnosis

For infants, potential causes of dysphagia include premature birth, congenital hiatal hernia, bronchopulmonary dysplasia, oesophageal atresia, trachea-oesophageal fistulas, congenital heart disease, gastro-oesophageal reflux, and neurological disorders[7].

Oropharyngeal cancers (more common in the 5th and 6th decades of life) can cause dysphagia via obstruction by the primary tumor or by the reduced movement of the mandible or tongue. Management options for oropharyngeal cancer are also known to cause dysphagia- surgical resection and subsequent reconstruction (for example, the base of tongue resection) removes the normal anatomy involved in moving food boluses and reconstructs it with immobile or hypo-mobile tissue. Radiotherapy of the head and neck region causes physiological changes (eg, mucositis, hyposalivation, and tissue fibrosis) that impair normal bolus formation and propulsion mechanisms.[8]

Neurological causes of dysphagia can occur acutely, for example, in stroke or traumatic brain injury. Conversely, they can progress more slowly over time as part of neurodegenerative conditions such as Parkinson disease.

Approximately 780,000 individuals in the US have a stroke in any given year, with aspiration pneumonia affecting one-third of stroke sufferers.[9] This is most often a result of abnormal/absent swallow reflex, inefficient lip closure, and limited tongue movement due to stroke-related cranial neuropathies. Therefore, providing nutrition via a tube for the first few weeks of a recent stroke is imperative if the patient cannot maintain adequate oral intake.[10]

With traumatic brain injuries, a common cause for dysphagia is the motor pattern reorganization following injury. This may be further prolonged by vocal cord paralysis following a long period of endotracheal tube intubation while in intensive care.

An estimated 80% of patients diagnosed with Parkinson disease have some degree of dysphagia (caused by both dopaminergic and non-dopaminergic disease pathways).[11] Aspiration pneumonia is a leading cause of death in Parkinson disease. Often, patients may not clinically demonstrate signs of dysphagia, but it is picked up on the videofluoroscopic swallow study.

Iatrogenic causes include endotracheal intubation (which can cause damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve supplying the vocal cord) and surgeries involving the head and neck or cardiothoracic surgery.

With aging, abnormalities in the cough reflex may develop due to reduced sensitivity in both the pharynx and larynx. Coupled with a delay in the initiation of the swallowing reflex and the slowing of food boluses passing along the oral and pharyngeal stages of swallowing, illness can cause the elderly to be more prone to dysphagia and aspiration pneumonia. An estimated 13% of nursing home residents are deemed to have some degree of dysphagia. Carer providers need to liaise with speech and language therapists to identify individuals who are considered vulnerable.

Other causes of dysphagia include:

38% of patients with multiple sclerosis, ALS (80% of patients are affected by the advanced stages of this disease. One in 3 patients demonstrates dysphagia from bulbar palsy.[12][13] Cranial nerves IX, X, and XII are affected), muscular dystrophy, myasthenia gravis, dementia, and spinal cord injuries.[14][15][16]

Normal and Critical Findings

To be able to interpret videofluoroscopic swallow studies, it is important to appreciate the stages of a normal swallow. These can be divided into oral preparatory, oral, pharyngeal, and oesophageal stages as follows:

For liquids, the bolus is placed on the anterior mouth floor or against the hard palate. The soft palate and posterior tongue form a seal to prevent liquid from entering the oropharynx. The tongue tip is then raised to the hard palate, propelling the liquid bolus into the pharynx, with the posterior tongue lowering to open access into the oropharynx. Food boluses are manipulated by the tongue backward along the palate while the jaw opens to allow the bolus to enter the pharynx. It arrives at the valleculae for the pharyngeal stage.

With the pharyngeal stage of swallowing, the nasopharynx becomes separated through soft palate elevation- this prevents food regurgitation into the nasopharynx. At the same time, the base of the tongue retracts to manipulate the bolus against the pharyngeal wall. The pharyngeal constrictors contract from superior to inferior, propelling the food bolus downwards towards the esophagus. The pharyngeal stage has adaptations to help protect the airway from aspiration- the epiglottis moves to seal close the laryngeal vestibule, while the vocal folds close together to seal the glottis. At this point, the upper oesophageal sphincter opens by suprahyoid and thyrohyoid muscle contraction to allow entry into the esophagus.

At the oesophageal stage of swallowing, the bolus is propelled through the entire length of the esophagus by peristalsis. There is an initial relaxation of the muscle around the bolus, followed by muscle contraction that tracks the food bolus down past the lower oesophageal sphincter and into the stomach. Note the lower two-thirds of the esophagus is smooth muscle, with the autonomic nervous system controlling peristalsis, which is involuntary.[17]

The swallow is initially assessed in the lateral plane. This is to view the passage of the bolus in its entirety into the esophagus. Nasopharyngeal regurgitation, the elevation of the hyoid bone, tilting and sealing by the epiglottis, residual food in either the pyriform sinuses or valleculae and abnormal upper oesophageal sphincter opening are all standard endpoints for assessment. An additional benefit of the lateral plane is the ability to assess for the entry/penetration of test boluses into the airway passages (larynx) and to determine at what stage this may occur. The anterior-posterior plane is then examined, which provides the added benefit of determining asymmetry if pathology is present. Videofluoroscopy allows the calculation of the Oral Transit Time and Pharyngeal Transit Time to calculate the Oropharyngeal Swallowing Efficiency. The severity of aspiration (penetration) using the 8-point Penetration-Aspiration Scale (PAS), with 1 meaning the absence of penetration of contrast below the vocal cords.[18]

Poor oral control can be demonstrated in videofluoroscopy by material falling through the lips (eg, neuropathies), the inability of the subject to form a bolus using their tongue and to subsequently correctly position it in the oral cavity (eg, stroke), or by a lack of seal formation (posterior tongue not adequately contacting the soft palate) leading to leakage of material and possible laryngeal penetration and aspiration. Poor tongue coordination or hesitant initiation of swallowing can show stasis of material within the oral cavity. Failure of soft palate elevation during swallowing subsequently leads to an insufficient palatopharyngeal seal, resulting in nasopharyngeal regurgitation.

Critical findings demonstrated during laryngeal elevation include decreased hyoid bone elevation (it normally elevates to appose the angle of the mandible) and reduced epiglottis movement. The latter suggests impaired glottic protection with a significant risk of material entering the supraglottic region and leading to aspiration. Note that if contrast material enters the laryngeal vestibule, this is termed laryngeal penetration, while contrast entering below the vocal cords is termed aspiration. Material may be seen to remain in the valleculae or piriform sinuses after swallowing (pooling) - this is observed in cerebrovascular accidents and sometimes after radiation therapy.[19]

Cricopharyngeal prominence is observed with advanced age, oesophageal motility disorders, Zenker diverticulum, and cricopharyngeal achalasia.[20] It leads to the narrowing of the oesophageal lumen, therefore causing dysphagia. A Zenker diverticulum (posterior pharyngeal pouch) presents itself at Killian's dehiscence- a point of anatomical weakness between the cricopharyngeus and thyropharyngeus. Contrast material is regurgitated from the diverticulum post-swallow and can lead to overflow aspiration. The diverticular pouch is often typically visible on an anteroposterior view as well.[21]

Complications

Videofluoroscopic swallow study uses x-rays for image study. Due to the use of ionizing radiation, there is a recognized risk of cellular damage and potential cancer induction. The risk becomes higher with greater radiation doses used.

Some individuals may have allergies to the contrast material, and obtaining consent from the patient is important. Alternate materials, such as gastrograffin, may be used in such situations. As with other radiological investigations, pregnancy status needs to be determined before commencing the study.

As the patient is being assessed for dysphagia, the radio-opaque test boluses may enter the airway passages- ie, aspiration. This risk is reduced when the speech and language pathologist/therapist commences the study using a material with the easiest consistency for the patient to swallow before escalating to more difficult consistencies.

Clinical Significance

Overall, dysphagia increases the morbidity and mortality of patients. Therefore, dysphagia must be diagnosed and managed early to maintain the best possible quality of life for the individuals concerned. By promptly diagnosing and identifying the cause, healthcare professionals can personalize the patient's management.

Speech and language therapists determine a swallow's abnormal stage(s) and can suggest suggestions to the clinical team/carers/patient. Management plans can include advising that the patient becomes ‘Nil by Mouth’ and fed via a tube, eg, nasogastric tubes or percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy, requesting the patient avoid food of certain consistencies, eg, ‘soft diet only’ or using maneuvers when eating.

Interprofessional healthcare team members must keep updated with the latest guidelines and skillsets required to manage patients presenting with swallowing disorders. The American Board of Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders provides specialty certification. Speech and language pathologists/therapists have expertise in assessing, diagnosing, and managing individuals with dysphagia and work inter-professionally with dieticians, radiologists, nurses, doctors, and carers to improve the quality of life and minimize risk.[4]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Videofluoroscopic Swallowing Study. A still x-ray image taken from a videofluoroscopic swallowing study shows the oropharyngeal anatomy and includes evidence of mild residue (up to 25% of the available space) in the valleculae and pyriform sinuses. Additionally, a thin line of barium running down the front wall of the trachea indicates prior aspiration.

Contributed by A Aggarwal, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

Stages of the Swallowing Process. A: Bolus hold position, glossopalatal seal maintained. B: Tongue tip elevation, soft palate elevates to closure, and bolus passes mandible ramus. C: Bolus moves posteriorly as tongue moves backward, hyoid and larynx begin to ascend, and epiglottis tilting. D: Larynx closed, epiglottis inverted, UES begins to open. E: Pharynx constricts, tongue base against pharynx, maximum hyoid elevation, UES open. F: Bolus tail through UES, structures returning to rest.

Contributed by A Aggarwal, MD

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Holdiman A, Rogus-Pulia N, Pulia MS, Stalter L, Thibeault SL. Risk Factors for Dysphagia in Patients Hospitalized with COVID-19. Dysphagia. 2023 Jun:38(3):933-942. doi: 10.1007/s00455-022-10518-1. Epub 2022 Sep 15 [PubMed PMID: 36109398]

Li Y, Rao S, Chen W, Azghadi SF, Nguyen KNB, Moran A, Usera BM, Dyer BA, Shang L, Chen Q, Rong Y. Evaluating Automatic Segmentation for Swallowing-Related Organs for Head and Neck Cancer. Technology in cancer research & treatment. 2022 Jan-Dec:21():15330338221105724. doi: 10.1177/15330338221105724. Epub [PubMed PMID: 35790457]

Westmark S, Melgaard D, Rethmeier LO, Ehlers LH. The cost of dysphagia in geriatric patients. ClinicoEconomics and outcomes research : CEOR. 2018:10():321-326. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S165713. Epub 2018 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 29922079]

Rugiu MG. Role of videofluoroscopy in evaluation of neurologic dysphagia. Acta otorhinolaryngologica Italica : organo ufficiale della Societa italiana di otorinolaringologia e chirurgia cervico-facciale. 2007 Dec:27(6):306-16 [PubMed PMID: 18320837]

Lee JW, Randall DR, Evangelista LM, Kuhn MA, Belafsky PC. Subjective Assessment of Videofluoroscopic Swallow Studies. Otolaryngology--head and neck surgery : official journal of American Academy of Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2017 May:156(5):901-905. doi: 10.1177/0194599817691276. Epub 2017 Feb 14 [PubMed PMID: 28195753]

Batchelor G, McNaughten B, Bourke T, Dick J, Leonard C, Thompson A. How to use the videofluoroscopy swallow study in paediatric practice. Archives of disease in childhood. Education and practice edition. 2019 Dec:104(6):313-320. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2017-313787. Epub 2018 Oct 15 [PubMed PMID: 30322859]

Slaughter JL. Neonatal Aerodigestive Disorders: Epidemiology and Economic Burden. Clinics in perinatology. 2020 Jun:47(2):211-222. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2020.02.003. Epub 2020 Feb 19 [PubMed PMID: 32439108]

Massonet H, Goeleven A, Van den Steen L, Vergauwen A, Baudelet M, Van Haesendonck G, Vanderveken O, Bollen H, van der Molen L, Duprez F, Tomassen P, Nuyts S, Van Nuffelen G. Home-based intensive treatment of chronic radiation-associated dysphagia in head and neck cancer survivors (HIT-CRAD trial). Trials. 2022 Oct 22:23(1):893. doi: 10.1186/s13063-022-06832-6. Epub 2022 Oct 22 [PubMed PMID: 36273210]

Liu ZY, Wei L, Ye RC, Chen J, Nie D, Zhang G, Zhang XP. Reducing the incidence of stroke-associated pneumonia: an evidence-based practice. BMC neurology. 2022 Aug 11:22(1):297. doi: 10.1186/s12883-022-02826-8. Epub 2022 Aug 11 [PubMed PMID: 35953801]

Armstrong JR, Mosher BD. Aspiration pneumonia after stroke: intervention and prevention. The Neurohospitalist. 2011 Apr:1(2):85-93. doi: 10.1177/1941875210395775. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23983842]

Gong S, Gao Y, Liu J, Li J, Tang X, Ran Q, Tang R, Liao C. The prevalence and associated factors of dysphagia in Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in neurology. 2022:13():1000527. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2022.1000527. Epub 2022 Oct 6 [PubMed PMID: 36277913]

Level 1 (high-level) evidencePayne M, Morley JE. Editorial: Dysphagia, Dementia and Frailty. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2018:22(5):562-565. doi: 10.1007/s12603-018-1033-5. Epub [PubMed PMID: 29717753]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUhm KE, Yi SH, Chang HJ, Cheon HJ, Kwon JY. Videofluoroscopic swallowing study findings in full-term and preterm infants with Dysphagia. Annals of rehabilitation medicine. 2013 Apr:37(2):175-82. doi: 10.5535/arm.2013.37.2.175. Epub 2013 Apr 30 [PubMed PMID: 23705111]

Barker J, Martino R, Reichardt B, Hickey EJ, Ralph-Edwards A. Incidence and impact of dysphagia in patients receiving prolonged endotracheal intubation after cardiac surgery. Canadian journal of surgery. Journal canadien de chirurgie. 2009 Apr:52(2):119-24 [PubMed PMID: 19399206]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBhattacharyya N, Kotz T, Shapiro J. Dysphagia and aspiration with unilateral vocal cord immobility: incidence, characterization, and response to surgical treatment. The Annals of otology, rhinology, and laryngology. 2002 Aug:111(8):672-9 [PubMed PMID: 12184586]

Terré-Boliart R, Orient-López F, Guevara-Espinosa D, Ramón-Rona S, Bernabeu-Guitart M, Clavé-Civit P. [Oropharyngeal dysphagia in patients with multiple sclerosis]. Revista de neurologia. 2004 Oct 16-31:39(8):707-10 [PubMed PMID: 15514895]

Kou W, Carlson DA, Kahrilas PJ, Patankar NA, Pandolfino JE. Normative values of intra-bolus pressure and esophageal compliance based on 4D high-resolution impedance manometry. Neurogastroenterology and motility. 2022 Oct:34(10):e14423. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14423. Epub 2022 Jun 5 [PubMed PMID: 35661346]

Matsuo K, Palmer JB. Anatomy and physiology of feeding and swallowing: normal and abnormal. Physical medicine and rehabilitation clinics of North America. 2008 Nov:19(4):691-707, vii. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2008.06.001. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18940636]

Sugaya N, Goto F, Okami K, Nishiyama K. Association between swallowing function and muscle strength in elderly individuals with dysphagia. Auris, nasus, larynx. 2021 Apr:48(2):261-264. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2020.09.007. Epub 2020 Sep 23 [PubMed PMID: 32978005]

Zhu L, Chen J, Shao X, Pu X, Zheng J, Zhang J, Wu X, Wu D. Botulinum toxin A injection using ultrasound combined with balloon guidance for the treatment of cricopharyngeal dysphagia: analysis of 21 cases. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology. 2022 Jul:57(7):884-890. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2022.2041716. Epub 2022 Feb 25 [PubMed PMID: 35213271]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRandall DR, Chan R, Gomes D, Walker K. Natural History of Cricopharyngeus Muscle Dysfunction Symptomatology. Dysphagia. 2022 Aug:37(4):937-945. doi: 10.1007/s00455-021-10355-8. Epub 2021 Sep 8 [PubMed PMID: 34495387]