Anatomy, Head and Neck, Posterior Neck Triangle

Anatomy, Head and Neck, Posterior Neck Triangle

Introduction

The posterior neck triangle is a clinically relevant anatomic region that contains many important vascular and neural structures. The clinical aspect of the anatomy contained in the posterior neck triangle is useful for a wide variety of medical specialties, including anesthesiology, otolaryngology, physical medicine and rehabilitation, and others. Anatomic variations, as well as variations in nomenclature, exist among arteries and nerves in this region. This article will serve to mitigate ambiguity by providing alternative nomenclature when applicable.[1][2]

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

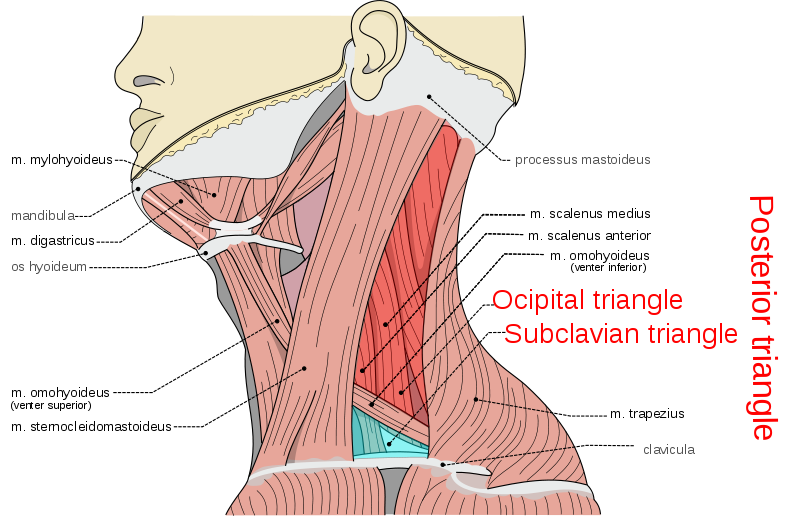

Identification of the anatomic structures that provide boundaries for the posterior neck triangle is clinically important when performing surgical intervention in this region. These borders include the trapezius muscle posteriorly, the sternocleidomastoid muscle anteriorly, and the middle one-third of the clavicle inferiorly. The union of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles at their insertion on the superior nuchal line of the occipital bone form the apex of the triangle. The posterior neck triangle is covered superficially to deep by the skin, superficial and deep cervical fascia, and the platysma muscle.

Bounding a large anatomic region, the posterior neck triangle further divides into two smaller triangles by the inferior omohyoid muscle. These subdivisions include the occipital and subclavian triangles. The occipital triangle is bounded by the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle, the trapezius muscle, and the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The subclavian triangle, sometimes referred to as the supraclavicular triangle, is bounded by the inferior belly of the omohyoid muscle, the clavicle, and the sternocleidomastoid muscle.[2][3]

Embryology

The embryologic derivation of the muscular boundaries of the posterior neck triangle includes the sixth branchial arch mesoderm. The sixth branchial arch mesoderm eventually separates into two independent masses that become the trapezius muscle and sternocleidomastoid muscle. Both the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles are formed partially from neural crest derivatives and partly from somites.[4]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Arterial supply within the posterior neck triangle can be challenging to describe based on anatomic variations that exist from the origin of various arteries in this region. The textbook definitions of anatomic vasculature are provided below. Further descriptions of common variants of the vasculature appear in the Physiologic Variants section.

The subclavian arteries are located at the inferior border of the triangle posterior to the clavicle. The common carotid arteries are branches of the early portion of the subclavian arteries and course just outside of the triangle but may encroach into its anatomic space as they travel superiorly. Following the bifurcation of the common carotid artery into the external and internal carotid arteries at the level of the fourth cervical vertebra, the external carotid is visible in the posterior neck triangle. The thyrocervical trunk can be found coursing from the subclavian artery and readily gives off the transverse cervical artery and suprascapular artery, which both course laterally across the posterior neck triangle.

Prominent veins coursing through the posterior neck triangle include the terminal portion of the external jugular vein located on the inferior portion, as well as the subclavian vein. The suprascapular vein and transverse cervical vein join the external carotid vein in the inferior portion of the triangle. The internal jugular vein courses deep to the sternocleidomastoid muscle and is susceptible to injury during dissection of the posterior neck triangle.

Lymphatic supply within the posterior neck triangle includes the occipital, transverse cervical, and supraclavicular chains of lymph nodes. The clinical relevance of the supraclavicular lymph node, also known as Virchow’s node, will be elaborated upon in the Clinical Significance section.[5][1]

Nerves

Consistent with the variation seen in the arterial supply of the posterior neck triangle, the spinal accessory nerve (cranial nerve XI), also expresses variation that will receive further elaboration in the Physiological Variants section.

The most clinically relevant nerve coursing through the posterior neck triangle is the spinal accessory nerve. This is due to its susceptibility to injury from surgical intervention in this area. Other nerves present in the triangle include trunks and branches of the brachial plexus, as well as the phrenic nerve supplied by the third, fourth, and fifth cervical spinal nerves.[6]

Muscles

The muscles that comprise the boundary of the posterior neck triangle in the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. The platysma muscle is found overlying the triangle superficially. Muscles coursing within the boundaries of the posterior neck triangle include the anterior, middle, and posterior scalene muscles as well as the omohyoid muscle. Superiorly, the semispinalis capitis and splenius capitis muscles insert near the apex of the junction of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles at the superior nuchal line of the occiput.[2]

Physiologic Variants

Arteries:

Conventional textbook nomenclature describes a prominent artery in the posterior neck triangle as the transverse cervical artery, a branch of the thyrocervical trunk branching from the subclavian artery. Multiple cadaveric dissection studies have sought to eliminate the use of this term in favor of more specific language to describe more correctly the arteries present in the posterior neck triangle. The following variants are common in frequency and arise from either the subclavian artery of the thyrocervical trunk:

- Cervico-scapular trunk: Gives rise to the superficial scapular and dorsal scapular arteries.

- Cervico-dorsal trunk: Gives rise to the cervical and dorsal scapular arteries

- Cervico-dorso-scapular trunk: Gives rise to the superficial cervical, dorsal scapular, and suprascapular arteries.

- Dorso-scapular trunk: Gives rise to the suprascapular and dorsal scapular arteries.

In addition to the above-listed trunks, many anatomic variants of arteries that arise directly from either the subclavian artery or thyrocervical trunk exist in varying frequency.

Nerves:

Physiologic variants of the spinal accessory nerve also exist within the posterior neck triangle. These include variants of the nerve that communicate with the cervical plexus, although effects on the motor function of innervated muscles are largely unknown. Another variant of the spinal accessory nerve passes under the anterior border of the trapezius muscle as opposed to the posterior border.[1][6]

Surgical Considerations

One of the most frequent surgical interventions performed in the posterior neck triangle includes radical neck dissection of lymph nodes along the sternocleidomastoid muscle after removal of head or neck squamous cell carcinoma. Performance of this surgery is routinely due to the prominence of metastasis from head and neck carcinomas through the lymph nodes found in the posterior neck triangle.

The most commonly reported complication from this surgery involves cervical stiffness and appearance-related issues resulting from fibrosis of tissue. Another more severe complication of surgery in this area is known as “shoulder syndrome” and results from damage to the spinal accessory nerve. This complication results in paralysis of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles and causes shoulder droop and pain in the neck and shoulders. Further complications include accidental transection of the transverse cervical and great auricular nerves resulting in numbness over the angle of the jaw and ear. One of the most serious complications from surgical intervention in the posterior neck triangle includes damage to the internal jugular vein.

Aside from complications due to radical neck dissection in the posterior neck triangle, arteries in this area are frequently used for flap design in plastic and reconstructive surgery.[1][7][5][8][9]

Clinical Significance

The clinical significance of anatomy contained in the posterior neck triangle is vast. Vessels found in the posterior neck triangle are harvested for use in plastic and reconstructive flap cases throughout the body. As previously mentioned, lymph nodes present in the posterior neck triangle are the most common areas of metastasis from head and neck cancers and are routinely dissected in surgical cases.

The left-sided supraclavicular lymph node, also known as Virchow’s node, is supplied by lymph vessels originating from the abdominal cavity that pass through the thoracic duct to enter the venous circulation in the left subclavian vein. This lymph node is clinically important as it can be used to aid in the discovery and diagnosis of carcinomas originating from the abdomen. An enlarged, firm, non-tender Virchow’s node is known as Troisier’s sign and can be indicative of cancer originating commonly from the stomach, ovaries, testicles, and kidneys.

The right-sided supraclavicular lymph node is also clinically relevant as it drains lymphatic fluid from the thorax. A firm, enlarged, non-tender right-sided supraclavicular lymph node can represent metastasis from lung or esophageal cancer, as well as Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Less common lymph node pathology found in the posterior neck triangle includes Castleman disease. Castleman disease results from angiofollicular lymph node hyperplasia or giant lymph node hyperplasia. The cause of Castleman disease is largely unknown but thought to be caused by either a chronic inflammatory reaction or viral etiology. Diagnosis of Castleman disease involves biopsy of the suspected lymph node followed by histopathologic evaluation. Some studies suggest that the lymph tissue hyperplasia seen in Castleman disease serves as a predisposing factor for progression to lymphoma or Kaposi’s sarcoma.[1][8][10][11]

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Weiglein AH, Moriggl B, Schalk C, Künzel KH, Müller U. Arteries in the posterior cervical triangle in man. Clinical anatomy (New York, N.Y.). 2005 Nov:18(8):553-7 [PubMed PMID: 16187318]

Ihnatsenka B, Boezaart AP. Applied sonoanatomy of the posterior triangle of the neck. International journal of shoulder surgery. 2010 Jul:4(3):63-74. doi: 10.4103/0973-6042.76963. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21472066]

Ryan LE, Nickel CJ, Padhya T. A Posterior Triangle Neck Mass in a Pediatric Patient. JAMA otolaryngology-- head & neck surgery. 2019 Jan 1:145(1):87-88. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2018.2931. Epub [PubMed PMID: 30452516]

Singh S, Chauhan P, Loh HK, Mehta V, Suri RK. Absence of Posterior Triangle: Clinical and Embryological Perspective. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research : JCDR. 2017 Feb:11(2):AD01-AD02. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/23896.9176. Epub 2017 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 28384846]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMeybodi AT, Lawton MT, Mokhtari P, Kola O, El-Sayed IH, Benet A. Exposure of the External Carotid Artery Through the Posterior Triangle of the Neck: A Novel Approach to Facilitate Bypass Procedures to the Posterior Cerebral Circulation. Operative neurosurgery (Hagerstown, Md.). 2017 Jun 1:13(3):374-381. doi: 10.1093/ons/opw024. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28521360]

Symes A, Ellis H. Variations in the surface anatomy of the spinal accessory nerve in the posterior triangle. Surgical and radiologic anatomy : SRA. 2005 Dec:27(5):404-8 [PubMed PMID: 16132192]

Gordon SL, Graham WP 3rd, Black JT, Miller SH. Acessory nerve function after surgical procedures in the posterior triangle. Archives of surgery (Chicago, Ill. : 1960). 1977 Mar:112(3):264-8 [PubMed PMID: 843216]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencede Langen ZJ, Vermey A. Posterolateral neck dissection. Head & neck surgery. 1988 Mar-Apr:10(4):252-6 [PubMed PMID: 3235357]

Aramrattana A, Sittitrai P, Harnsiriwattanagit K. Surgical anatomy of the spinal accessory nerve in the posterior triangle of the neck. Asian journal of surgery. 2005 Jul:28(3):171-3 [PubMed PMID: 16024309]

Lin CY, Huang TC. Cervical posterior triangle castleman's disease in a child - case report & literature review. Chang Gung medical journal. 2011 Jul-Aug:34(4):435-9 [PubMed PMID: 21880199]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFernández Aceñero MJ, Caso Viesca A, Díaz Del Arco C. Role of fine needle aspiration cytology in the management of supraclavicular lymph node metastasis: Review of our experience. Diagnostic cytopathology. 2019 Mar:47(3):181-186. doi: 10.1002/dc.24064. Epub 2018 Nov 23 [PubMed PMID: 30468321]