Introduction

The cerebral venous system divides into a superficial and deep component. The superior sagittal sinus is the major component of the superficial cerebral venous system, and knowledge of this structure and its variations are of practical clinical importance to neurosurgeons, neurologists, and radiologists in treating several conditions. A strong anatomical understanding of the superior sagittal sinus is crucial for the clinician, as this dictates the treatment approach for the patient. The superior sagittal sinus is a midline vein without valves or tunica muscularis that courses along the falx cerebri, draining many cerebral structures surrounding it.[1] First described in 1888 by Gowers, the dural venous sinuses are structures that were first mapped out and provided a basis for understanding various pathologies. Many surgeons and clinicians, including Cushing and Eisenhardt, eventually described the superior sagittal sinus in more detail, as well as dissection methods and anatomical variants.[2] This topic describes the basic anatomy and function of the superior sagittal sinus and various conditions associated with the superior sagittal sinus.

Structure and Function

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Structure and Function

The superior sagittal sinus is an unpaired venous structure that originates at the junction of the frontal and ethmoid bone, directly posterior to the foramen cecum close to the crista galli. The extensive length of the superior sagittal sinus makes it the largest dural venous sinus, rendering it most susceptible to injury.[1] The distance from the foramen cecum varies in each individual but tends to remain within 1 to 12 millimeters.[2] After its origin, the superior sagittal sinus follows the superior cranial vault. It travels inferior to the sagittal suture of the cranium and superior to the falx cerebri within 2 dural leaves. It is important to note that the superior sagittal sinus can lie within 1 centimeter lateral to the sagittal suture, with a tendency for most to lie to the right of the suture. Definitive localization of the superior sagittal sinus with brain CT (computed tomography) or MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) is a recommendation before making burr holes close to the sagittal suture.[3][4]

As the superior sagittal sinus continues, it courses towards the confluence of sinuses at the posterior cranium. The superior sagittal sinus drains the lateral aspects of the anterior cerebral hemispheres.[4] The superior sagittal sinus eventually progresses posteriorly to the confluence of sinuses, where it terminates. Anatomic variations of the intracranial dural venous sinuses are frequent but most commonly involve the transverse sinus in the deep system. However, the rostral part of the superior sagittal sinus may be narrow or sometimes even absent and replaced by 2 superior cerebral veins joined behind the coronal suture. The examiner should recall this fact when evaluating cerebral venous thrombosis (CVT), which 1 can more reliably identify in the posterior aspect of the superior sagittal sinus.

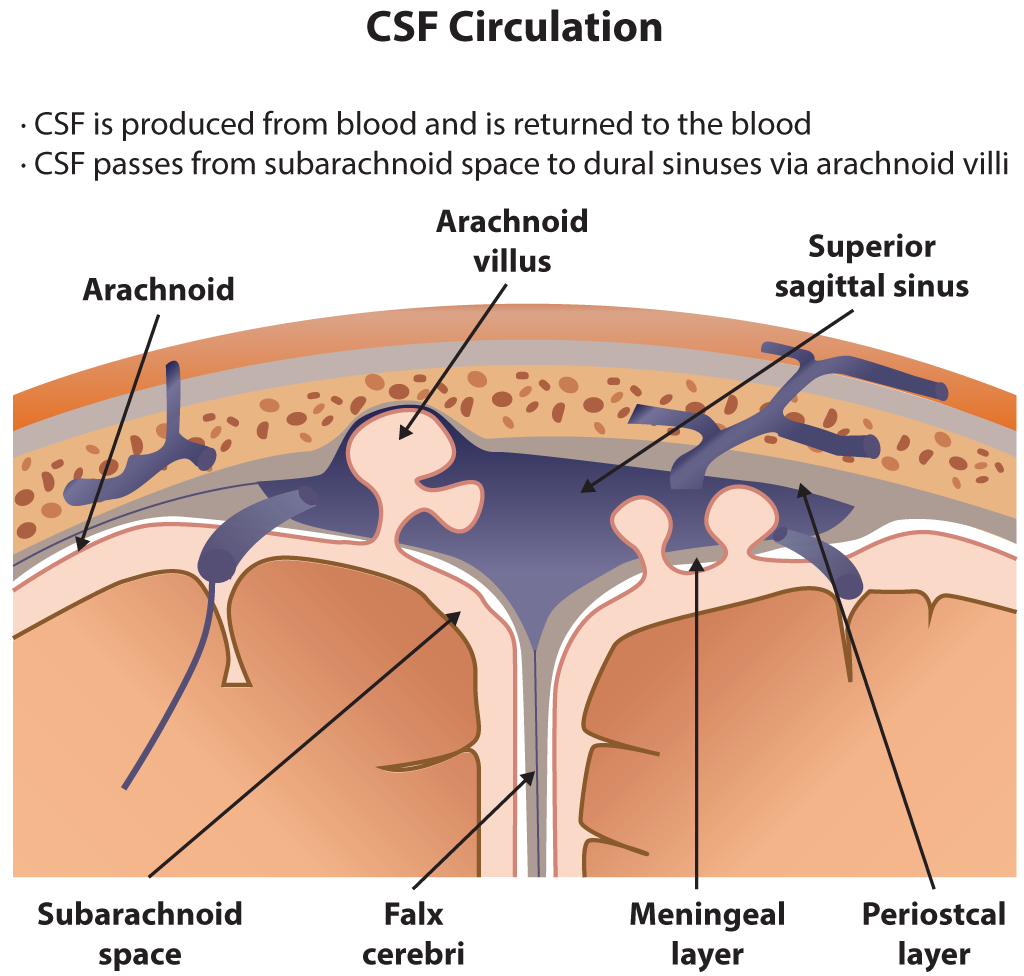

In addition to draining blood from the cerebral cortex, the superior sagittal sinus plays a significant role in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) homeostasis. The largest number of arachnoid villi and granulations, which act as 1-way valves moving CSF into the dural sinuses, exist in the walls of the superior sagittal sinus, conveying CSF into the superior sagittal sinus for recirculation and elimination. This circulation of CSF is crucial to volume regulation within the cortex and ventricular space, as dysregulation of this process can cause multiple neurological deficits, including papilledema secondary to increased intracranial pressure.[4] See Image. Cerebrospinal Fluid Circulation.

Embryology

The embryological origin of the cerebral venous system is more complex than that of the cerebral arterial system. The formation of the whole venous system begins during the 3 and 4 weeks of gestation, eventually forming from the aortic arch. The development of the cerebral venous system closely follows that of the neural tube in a caudal to rostral manner. The superior sagittal sinus has been theorized to originate from a plexiform of vessels and eventually combine to form a single vascular channel. Also, its position within the cranial vault depends on embryological signals from the falx cerebri. These positional signals may explain the reason for the preferential laterality of the position of the superior sagittal sinus relative to the sagittal suture.[1][3]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

The superior sagittal sinus drains the bilateral cerebral hemispheres and serves as the common midline venous structure that receives blood from multiple draining vessels within the cortical hemispheres. The superior sagittal sinus, in particular, also drains the cerebrospinal fluid from the subarachnoid space through the arachnoid villi (figure 1). There are numerous normal variants of the draining vessels of the superior sagittal sinus. The average number of draining vessels ranges from 13 to 19 vessels for each hemisphere of the cortex. This number is generally equal on each side for any given individual. The superior sagittal sinus ultimately drains into the transverse sinus and then into the straight sinus (figure 2)

The most significant draining vessel of the superior sagittal sinus is the vein of Trolard, which connects the superficial middle cerebral vein to the superior sagittal sinus. The Rolandic vein, which drains the brain's primary motor and somesthetic sensory cortices, is another significant tributary of the superior sagittal sinus.[5] Since the superior sagittal sinus lies between the 2 leaves of the dura mater, terminal draining veins must cross through the subdural space to reach the superior sagittal sinus. These terminal draining veins are called bridging veins, which are incredibly important in the pathogenesis of subdural hematomas.[6] In addition to the intracerebral tributaries, multiple “emissary veins” connect the extracranial scalp veins to the superior sagittal sinus.[7]

Surgical Considerations

The neurosurgeon should be extremely careful while operating in the region of the superior sagittal sinus. When performing a craniotomy over the sinus, it is desirable to place bur holes on either side, straddling the sinus, and carefully dissect it from the overlying bone before completing the craniotomy. Bleeding from the sinus can be life-threatening.

Clinical Significance

Due to its multiple connections, including its significant role in draining the cerebral hemispheres as well as receiving blood from the diploic, meningeal, and emissary veins from the scalp, there are multiple complications and pathological processes that can affect the superior sagittal sinus. This section briefly discusses some of the more common pathologies affecting the sinus. First and foremost, the superior sagittal sinus is prone to thrombosis, presenting with various features from headaches, hemiparesis, sixth nerve palsy, papilledema, nausea, and seizures. It has to merit consideration in the context of a cryptogenic stroke in a young woman on birth control pills due to the hypercoagulable state. Additional risk factors for superior sagittal sinus thrombosis include pregnancy, previous venous thrombosis, malignancy, Bechet disease, factor V Leiden mutation, prothrombin gene mutation, and protein C and protein S deficiency. Septic thrombosis of the superior sagittal sinus is rare and most frequently accompanies bacterial meningitis or paranasal nasal sinus infection.[2]

Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis is of extreme clinical importance due to the irreversible consequences that can occur secondary to the increased intracranial pressure associated with dural vein occlusion. Due to its major role in CSF circulation, vein obstruction often leads to dysregulation of the normal CSF drainage pathway, potentially causing increased intracranial pressures. In these instances, the edema produced after venous occlusion is another mechanism of increased intracranial pressure.[8] The primary goal when managing patients with superior sagittal sinus thrombosis is the stabilization and prevention of cerebral herniation. Heparin is the mainstay of acute treatment, but recently, mechanical thrombectomy has also been recommended on a limited basis. Identifying this condition can be challenging, but in the face of a high index of clinical suspicion, CT venography, magnetic resonance venography, or intentional catheter arteriography with attention to the venous phase can be diagnostic.[9]

In addition to direct vessel thrombosis, the superior sagittal sinus is often implicated in the development of meningiomas due to its intimate proximity to the falx cerebri. When surgical intervention is necessary for these situations, the clinician must account for a tumor that may involve the superior sagittal sinus, as this often time complicates gross resection, resulting in suboptimal tumor resection with increased rates of recurrence. When intracranial pressure increases, there is increased reverse flow of venous blood through the emissary and diploic veins of the scalp and cranium, leading to increased rates of scalp, skull, and intracranial hemorrhage during craniotomies. In addition to being aware of the increased rate of bleeding, the surgeons must also know the location of the superior sagittal sinus relative to the sagittal suture and take extreme caution to avoid injuring the sinus while creating burr holes.[5]

Dural arteriovenous fistulas involving the superior sagittal sinus are rare but are associated with life-threatening venous hypertension and intracranial hemorrhage. Dural arteriovenous fistulas are aberrant, abnormal connections between the dural arteries and veins, leading to a high-pressure intracranial vascular system prone to bleeding. A variety of techniques exist for managing this condition, such as embolization or open total resection; however, these have correlations with a significant risk of hemorrhage, ischemic stroke, or further damage to normal surrounding vasculature.[10]

The superior sagittal sinus is a vital structure that is involved in a variety of potentially life-threatening conditions. Proper diagnosis requires familiarity with its anatomy (including anatomic variants) and a high index of clinical suspicion regarding its protean clinical presentations. The involvement of the superior sagittal sinus should be considered in presentations as varied as papilledema, cryptogenic stroke, seizures, or changes in mental status. Firm diagnosis ultimately rests upon neuroradiologic evaluation, with CT venography (CTV), magnetic resonance venography (MRV), and conventional catheter angiography being the modalities of choice.

Intracranial sinus evaluation with CTV or MRV is a particularly essential modality in the evaluation of headaches, frequently occurring in obese females, associated with visual obscurations, pulsatile tinnitus, and the potential permanent blindness due to idiopathic intracranial hypertension IIH(pseudotumor cerebri). Venous sinus thrombosis is identified frequently in cases of IIH. The reality is that beyond the specialties of ophthalmology or neuro-ophthalmology, the current level of physical diagnostic skills evaluating the optic fundus with direct ophthalmoscopy is almost universally inadequate. The diagnosis of papilledema is frequently delayed, with the disastrous consequences of permanent visual loss.

CVT is an important cause of stroke particularly in young adults (two-thirds of which are young females) caused by complete or partial occlusion most frequently involving the superior sagittal sinus but the other venous sinuses as well. Risk factors include pregnancy, estrogen replacement therapy, malignancy, dehydration, prothrombotic conditions including antiphospholipid antibody syndrome, prothrombin gene mutation, factor V Leiden mutation, protein S/C deficiency, infections involving the ears, mouth, and paranasal sinuses. However, a rare cause of all strokes (1-2%), CVT thrombosis with brain infarction is often delayed or missed entirely. Symptoms related to superior sagittal sinus thrombosis are multiple including headache, blurred vision, nausea, vomiting, aphasia, hemisensory loss/hemiparesis, and seizures. Diagnosis is facilitated by CTV and MRV in conjunction with standard CT and MR imaging, demonstrating areas of infarction uncharacteristic of a particular arterial distribution and frequently associated with varying degrees of intraparenchymal hemorrhage (figure 3). A high index of suspicion and knowledge of the risk factors, patient demographics, and neuroimaging features facilitate prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Reis CV, Gusmão SN, Elhadi AM, Dru A, Tazinaffo U, Zabramski JM, Spetzler RF, Preul MC. Midline as a landmark for the position of the superior sagittal sinus on the cranial vault: An anatomical and imaging study. Surgical neurology international. 2015:6():121. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.161241. Epub 2015 Jul 21 [PubMed PMID: 26290772]

Patchana T, Zampella B, Berry JA, Lawandy S, Sweiss RB. Superior Sagittal Sinus: A Review of the History, Surgical Considerations, and Pathology. Cureus. 2019 May 3:11(5):e4597. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4597. Epub 2019 May 3 [PubMed PMID: 31309022]

Bruno-Mascarenhas MA, Ramesh VG, Venkatraman S, Mahendran JV, Sundaram S. Microsurgical anatomy of the superior sagittal sinus and draining veins. Neurology India. 2017 Jul-Aug:65(4):794-800. doi: 10.4103/neuroindia.NI_644_16. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28681754]

Bayot ML, Reddy V, Zabel MK. Neuroanatomy, Dural Venous Sinuses. StatPearls. 2024 Jan:(): [PubMed PMID: 29489265]

Bi N, Xu RX, Liu RY, Wu CM, Wang J, Chen WD, Liu J, Xu YS, Wei ZQ, Li T, Zhang J, Bai JY, Dong B, Fan SJ, Xu YH. Microsurgical treatment for parasagittal meningioma in the central gyrus region. Oncology letters. 2013 Sep:6(3):781-784 [PubMed PMID: 24137410]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFamaey N, Ying Cui Z, Umuhire Musigazi G, Ivens J, Depreitere B, Verbeken E, Vander Sloten J. Structural and mechanical characterisation of bridging veins: A review. Journal of the mechanical behavior of biomedical materials. 2015 Jan:41():222-40. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.06.009. Epub 2014 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 25052244]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMurlimanju BV, Saralaya VV, Somesh MS, Prabhu LV, Krishnamurthy A, Chettiar GK, Pai MM. Morphology and topography of the parietal emissary foramina in South Indians: an anatomical study. Anatomy & cell biology. 2015 Dec:48(4):292-8. doi: 10.5115/acb.2015.48.4.292. Epub 2015 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 26770881]

Gupta RK, Jamjoom AA, Devkota UP. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis presenting as a continuous headache: a case report and review of the literature. Cases journal. 2009 Dec 21:2():9361. doi: 10.1186/1757-1626-2-9361. Epub 2009 Dec 21 [PubMed PMID: 20062608]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSiegert CE, Smelt AH, de Bruin TW. Superior sagittal sinus thrombosis and thyrotoxicosis. Possible association in two cases. Stroke. 1995 Mar:26(3):496-7 [PubMed PMID: 7886732]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceOhara N, Toyota S, Kobayashi M, Wakayama A. Superior sagittal sinus dural arteriovenous fistulas treated by stent placement for an occluded sinus and transarterial embolization. A case report. Interventional neuroradiology : journal of peritherapeutic neuroradiology, surgical procedures and related neurosciences. 2012 Sep:18(3):333-40 [PubMed PMID: 22958774]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence