Introduction

Heavy metals are defined differently by different people. In health parlance, they are naturally occurring substances that accumulate and cause damage to the environment and living beings, including humans. They also include substances known as semimetals or metalloids that can have the same deleterious effects. Humans are exposed to heavy metals through inhalation, ingestion, or contact with the skin. Environmental pollution with heavy metals can result in contamination of air, water, sewage, seawater, and waterways and can accumulate in plants, crops, seafood, and meat and indirectly affect humans. Some occupations have an increased risk for particular heavy metals exposure and toxicity. Some heavy metals, known as non-threshold heavy metals, can cause toxicity even at very low concentrations. Factors influencing the risk of toxicity include age, body weight, genetics, route of acquisition, duration of exposure, amount, health, nutritional status, and a combination of heavy metals. Some preparations used in complementary medicine can result in toxicity.[1]

Symptoms and signs of heavy metal toxicity vary with the substance and can be due to acute exposure to large amounts or chronic exposure to repeated small quantities, which can result in cumulative toxicity. Many body systems can be affected. Toxic exposure to 2 or more heavy metals can lead to more damage than a single heavy metal. Investigations include urine, blood, skin, nail, and hair tests. Management includes preventing any further exposure, removing the offending agent using chelating agents, supportive therapy, and patient education. Prevention or minimizing exposure is necessary, and laws exist to this effect. Public health measures include monitoring air, water, foods, and at-risk individuals, as well as environmental manipulation of soil, water, and sewage.

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

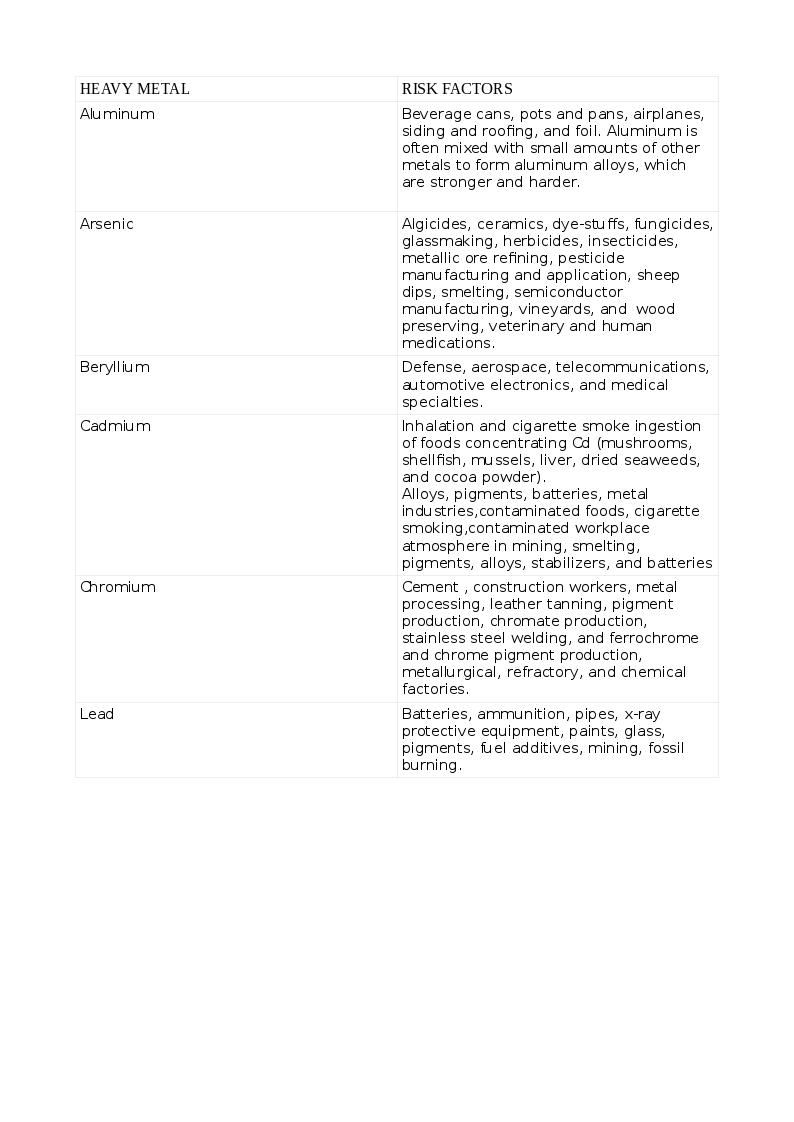

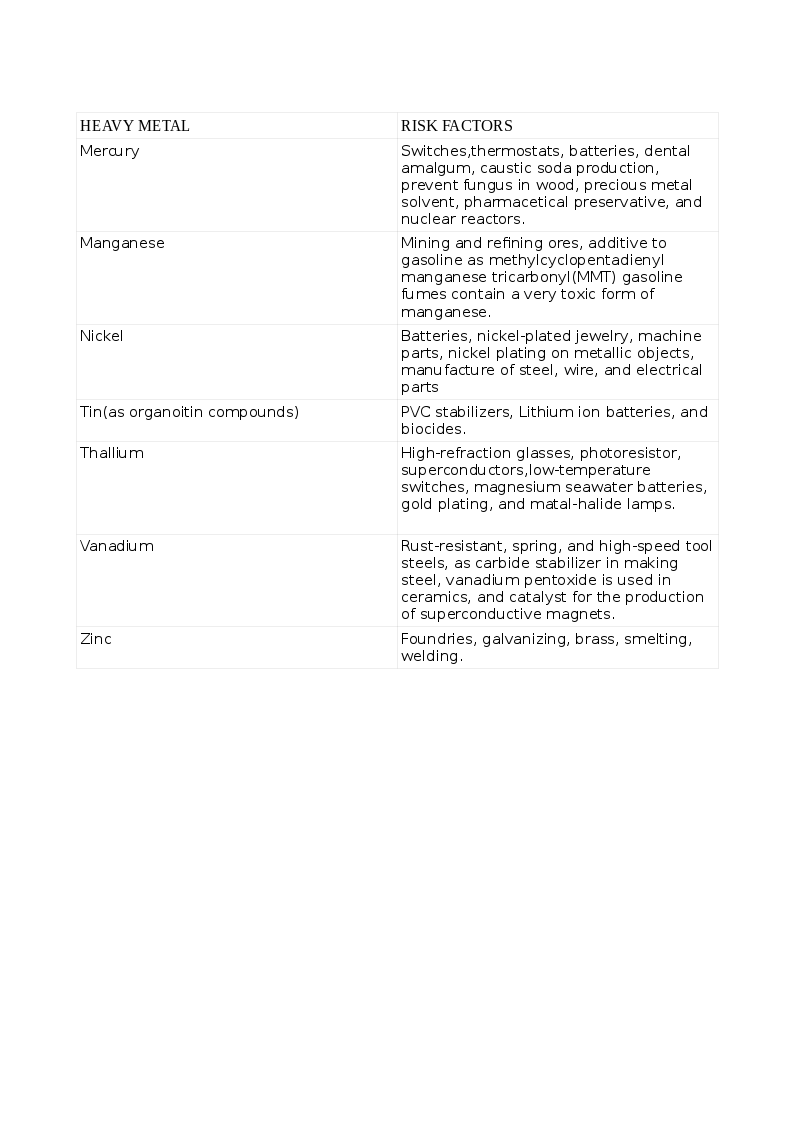

Heavy metals are dense, naturally occurring elements that cause health hazards by accumulating in the environment and living beings. Some elements like Arsenic (As) share properties of both metals and non-metals, are known as semimetals or metalloids and listed as heavy metal due to the toxic effects similar to metals. The common list of non-essential heavy metal that cause toxicity includes Arsenic (As), Cadmium (Cd), Lead (Pb), Mercury (Hg), and those that are essential to humans in trace quantities for various cellular activities like Cobalt (Co), Copper (Cu), chromium (Cr), Iron (Fe), Manganese (Mn), Molybdenum (Mo), Nickel (Ni), Selenium (Se) and Zinc (Zn). Exposure to heavy metals can be natural or occupational. The various heavy metals and the risks for their toxicity appear in the tables. See Tables. Risk Factors for Heavy Metal Toxicity, 1 and 1A.

Toxicity can result from inhalation, ingestion, and skin contamination. Humans can acquire heavy metals due to activities harnessing nature like mining, fossil-burning, industrial, agriculture, consuming plants, seafood, and meat that have accumulated these heavy metals from contaminated soil, waterways, and seawater. Toxicity with multiple heavy metals can be more pronounced and cause tremendous morbidity. Some indigenous medicinal preparations contain toxic amounts of heavy metals. Children are more susceptible than adults. While acute toxicity results from short exposure to large doses, long-term exposure to smaller amounts results in chronic toxicity.

Industrial waste containing Hg is released into the waters. Aquatic microbes convert inorganic Hg (iHg) to organic Hg (CH3Hg). Fish consume this, and bigger fish consume the smaller fish. Humans consume the bigger fish and thus complete the food cycle and suffer heavy metal toxicity. When refurbishing old buildings, care is necessary when removing flaky, loose paint. Sanding facilitates Pb and other paint toxins to spread into the dust and atmosphere, so alternatives like suctioning or vacuuming should be used.

Epidemiology

Heavy metal toxicity is a worldwide problem. However, the incidence and magnitude of the toxicities of individual heavy metals vary with the geographical location, natural soil content, habits, customs, location of industries, regulatory measures to contain pollution, healthcare facilities to detect heavy metal toxicity, and individual factors like nutritional status and genetics. When an heavy metal is released into the air, water, or soil, it can be absorbed by plants, crops, consumed by cattle and fish, and finally, end up in humans to complete the food chain.

Industrial and workplace exposure can result in heavy metal toxicity by inhalation, ingestion, or skin contact. The World Health Organization has listed 10 major pollutants, 4 of which are heavy metals. Groundwater contaminated with heavy metals can be consumed by humans, resulting in chronic heavy metal toxicity. An example is the high level of arsenic in the groundwater in Bengal, India, and neighboring Bangladesh, where the concentration of arsenic in the water is far above permissible limits.[2]

Time and again, there have been reports of heavy metal toxicity occurring in epidemic proportions; this has resulted from a rather careless release of toxic industrial effluents into the air, soil, sea, and waterways. Hunter-Russell syndrome occurred in a seed-packing factory in England due to the inhalation of methyl mercury, which was sprayed as an insecticide. The industrial release of methyl mercury into rivers and seawater resulted in poisoning and deaths in Japan, infamously known as Minamata disease. Another Japanese example is Cd accumulation in bones with resultant pains and fractures, the so-called "Itai-Itai (it hurts-it hurts) disease."[3] An epidemic of mercury poisoning occurred in Iraq, where grains sprayed with insecticide were consumed. A well-known case is groundwater contamination with chromium VI in California by a gas company that released its waste into the region's groundwater. Epidemiological studies have shown the association of heavy metal exposure and chronic diseases like diabetes, kidney disease, degenerative neurological conditions, skin ailments, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular disease, and cancer.[4][5][6]

Pathophysiology

Heavy metals generate metal-specific free radicals or reactive oxygen species (ROS) that cause oxidative stress to cells.[7] These result in:

- DNA damage, impaired DNA repair, cell apoptosis, or carcinogenesis.

- Peroxidation of cell membrane lipids and cell damage

- Inactivation of the enzyme proteins.

- Prevention of protein folding.

- Protein aggregation.

- Conformational changes that affect their structure and function and cause cell damage.

Examples of free radicals include:

- Hydroxyl radical (OH)

- Superoxide (O2-)

- Hydrogen peroxide. (H2O2)

- Peroxyl radical (ROO)

- Nitric oxide (NO)

NO can bind to ROS to form reactive nitrogen species, which are again harmful to cells.[8]

A heavy metal, when ingested, is acted upon by gastric acid and undergo oxidation. The oxidized heavy metal has a high affinity for enzymes and other proteins to form strong and stable bonds. Commonly, thio groups are attracted to heavy metal binding. In this way, enzymes are inhibited, products downstream are not produced, and biological functions are impaired. An example is the glutathione reductase enzyme affected by arsenic, restricting the removal of ROS. Inorganic As is toxic and is biotransformed to the end-metabolites monomethylarsonic acid (MMA) and dimethyl arsinic acid, which are excreted in the urine and are a measure of chronic esposure. An intermediate, monomethylarsonic acid III, accumulates in tissues and is a carcinogen.[9]

Heavy metals inhibit protein folding, cause misfolding, and aggregation, which damages cells and disrupts function. Pb and CH3Hg are lipophilic and easily cross cell membranes, especially of the tissues high in lipids like the central nervous system. Here they are sequestered and remain indefinitely, are difficult to remove by ordinary means and produce long-lasting neurotoxicity. Pb replaces Fe, Ca, Mg, and interferes with various cellular functions, including neural transmission.[10] Pb acts as a non-competitive inhibitor of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR), especially in the hippocampus, and interferes with learning and memory. It inhibits several enzymatic steps in hemoglobin synthesis and causes anemia.

A metalloprotein enzyme (zinc-finger metalloprotein) is affected by a heavy metal like Cd, which displaces the trace essential element Zn from the enzyme and inactivates it. Cd and Pb replace Ca in bones and result in osteoporosis and fractures. Cd causes a Fanconi like syndrome in the proximal S1 segment of the renal tubule and results in losses of phosphate, calcium, amino acids, bicarbonate, and results in hypophosphatemia, low bicarbonate, and proximal tubular acidosis; increased mobilization of calcium from the bone which coupled with increased renal excretion stimulates the parathyroid hormone secretion, causing further bone loss. There is inhibition of the 1-alfa hydroxylase enzyme in the kidney by Cd and, therefore, decreased active vitamin D3 production and less intestinal calcium absorption to compound the problem. Cd inhibits the osteoblastic conversion of bone tissue stem cells and stimulates osteoclasts, acting at the level of the bone in enhancing bone loss.[11] Mn accumulates in the mitochondria of neurons and glial cells, disrupting ATP synthesis and increasing ROS and cell damage. Hg in the inorganic form can inhibit catechol o-methyl transferase (COMT), the enzyme catalyzing the degradation of catecholamines, by inactivating its cofactor S-adenosyl methionine, resulting in unexplained hypertension. Omega-3 fatty acids and Se retard Hg toxicity.[12] Genetic polymorphisms in the gene for COMT may explain the differences in the neurobehavioral effects of Hg toxicity.[13]

History and Physical

Heavy metal toxicity is, in general, underdiagnosed, and a high index of suspicion is needed. A history of occupational exposure is vital. When taking a medication history, attention to alternative medicine intake is easily overlooked. Many medications in Chinese, Ayurveda, homeopathy, and Siddha systems contain heavy metals in significant quantities that, when taken over time, may cause toxicity. Living in older homes is a risk factor for lead toxicity through water pipes and flaking paint and dust. Living in a neighborhood that has heavy metal contamination (in industrial belts)is a definite risk factor. A parent who suffers exposure at work may contaminate his family when he gets home.

Heavy metal exposure during the antenatal period may yield clues to problems in newborns and infancy. Young children are more vulnerable to heavy metal toxicity. A previously active and healthy child may present with poor play, distractibility, falling grades at school, abdominal pain, anemia, and delay or retarded development.

Accidental consumption is more common, but in some cases, the cause is suicidal and prompt urgent mental health consultation. Exposure to more than 1 heavy metal cause profound symptoms compared to one heavy metal alone. Acute exposure is usually dramatic in presentation. Inhalation of heavy metals causes respiratory symptoms, topical contamination, and skin lesions, and ingestion mimics acute gastroenteritis or dysentery.

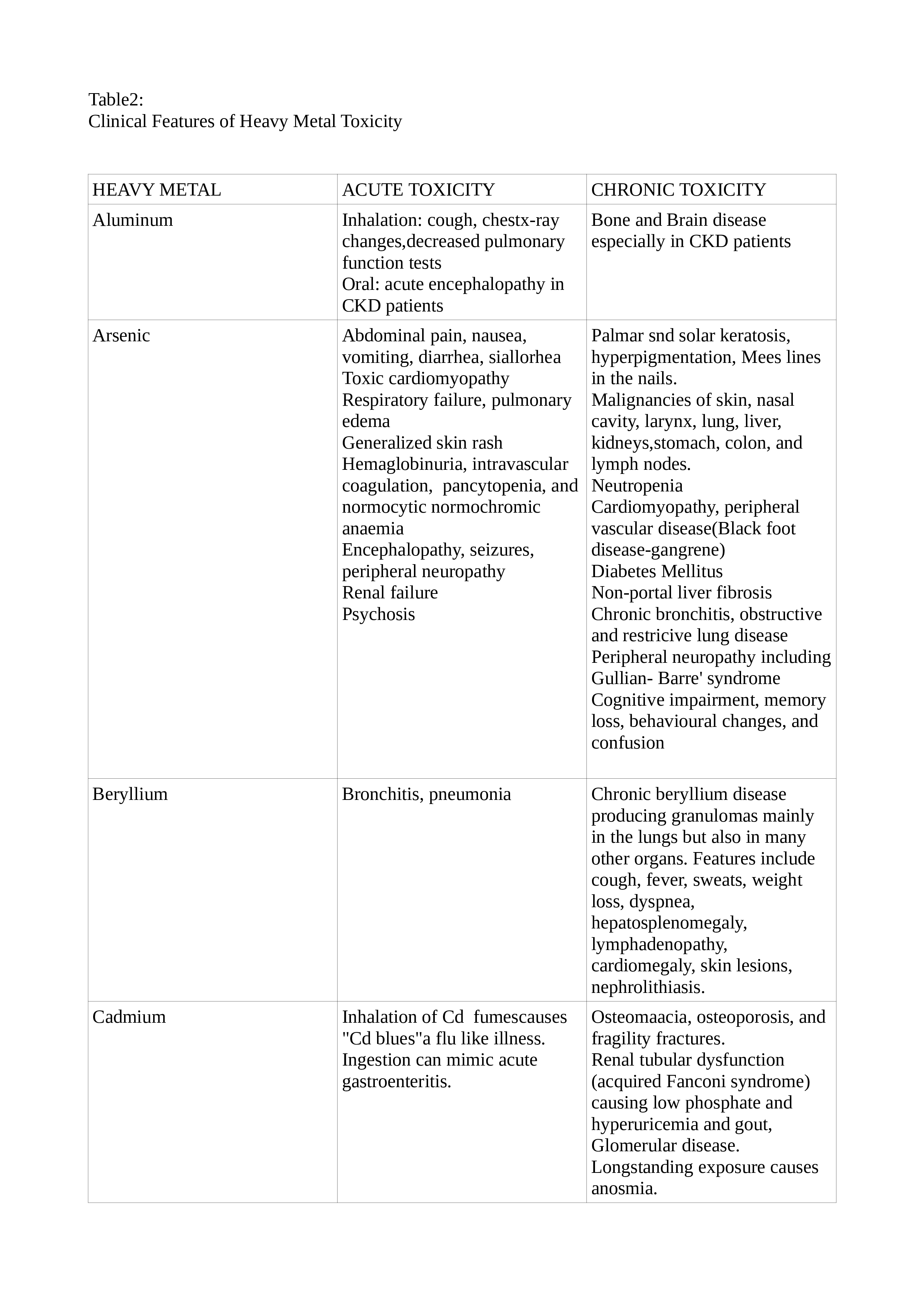

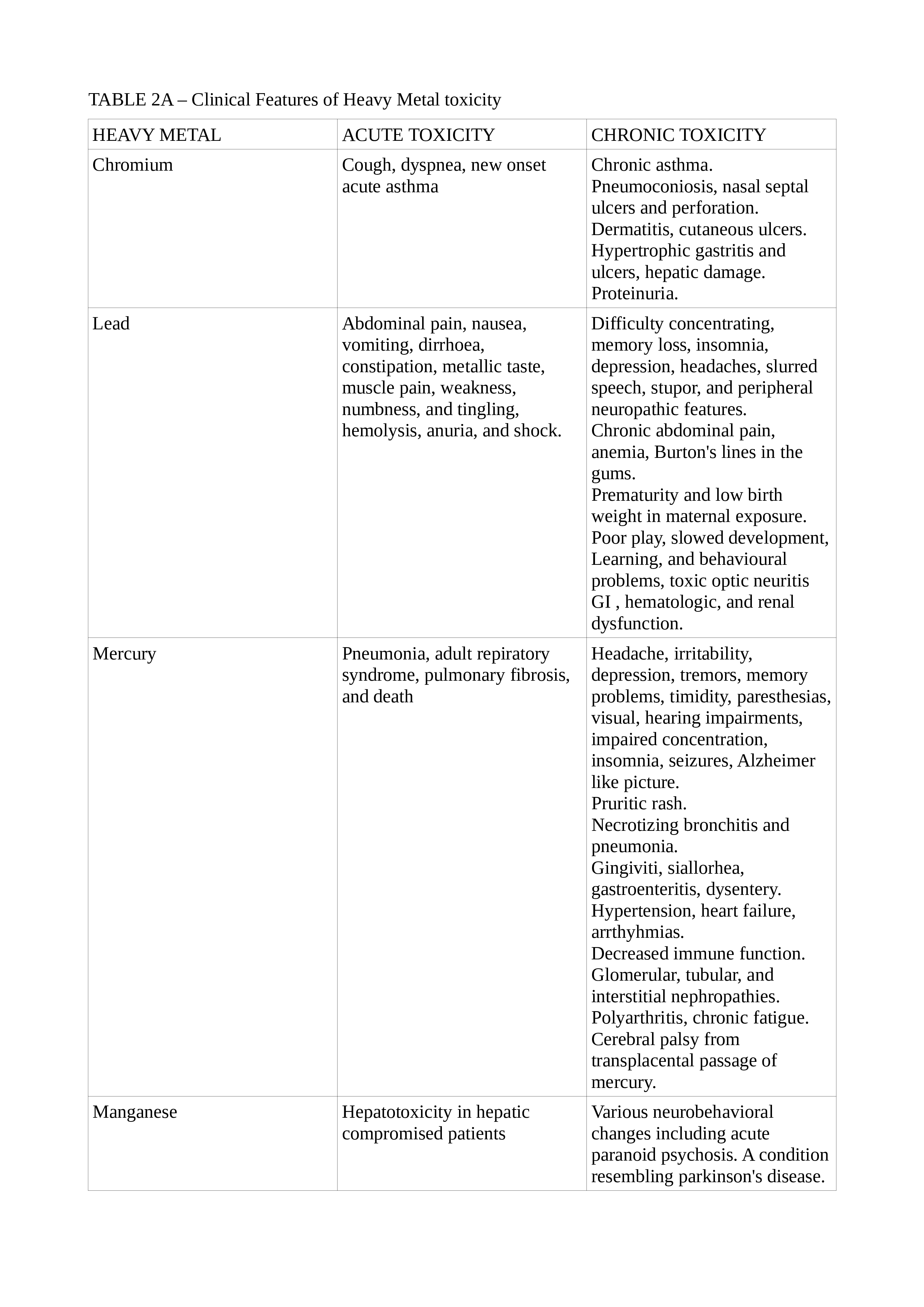

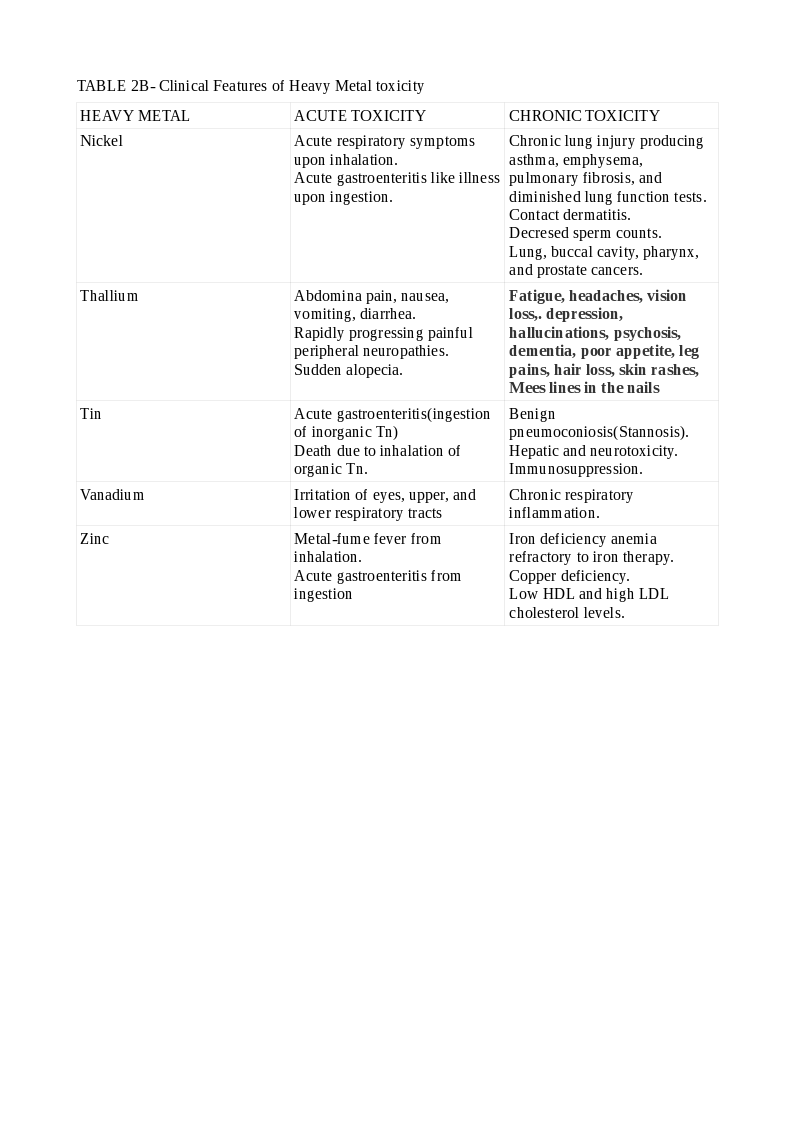

Chronic exposure is more difficult to detect and needs a high index of suspicion. Depending on the organ system involved, the symptoms vary. Typical findings may be present only in selected cases, while the majority may be non-specific. Lead toxicity may cause a blue line in the gingiva, mercury toxicity may present with Mees lines in the nails, while chromium (Cr) toxicity may present as cutaneous ulcers that appear punched out with thickened raised edges involving the extensor surface of the forearms and web spaces of the hands. See Tables. Clinical Features of Heavy Metal Toxicity, 2, 2A, and 2B.[11][14][15][16][17][18][19][20]

Evaluation

The examination of blood, urine, hair, nail, and tissues may be utilized to confirm heavy metal toxicity. The patient should refrain from seafood for at least 48 hours before the tests. If gadolinium or iodine-contrast was used, the waiting time increases to 96 hours. In industrial workers, blood and urine testing for heavy metal exposure are necessary to monitor safe permissible limits and specimens should be obtained at the end of the workweek; for example, if Friday is the last day of the workweek, the test specimens should be obtained at the end of that day to affect actual levels of exposure.

Special metal-free tubes for blood or acid-washed containers for urine maximize accuracy. The level of heavy metals in the blood or urine reflect current exposure and not accurately reflect body stores from chronic exposure. Symptoms may not correlate with blood levels, and profound symptoms may be apparent in individuals with heavy metal levels only slightly above normal. Sometimes, a chelation challenge is necessary to strengthen the diagnosis and is the most accurate method of establishing the diagnosis of heavy metal toxicity.

Ancillary tests like hemograms to detect anemia and liver and renal function tests are often helpful. Hypophosphatemia, hyperphosphaturia, hypercalciuria, proteinuria with low molecular weight proteins like beta-2 microglobulin, elevated alkaline phosphatase, and bone markers, decreased serum 1,25 dihydroxy vitamin D3, and increased intact PTH are all useful in documenting Cd-induced bone disease.[3] An abdominal X-ray may show a radioopaque foreign body that contains heavy metal. A chest X-ray may show changes due to inhalation exposure. These changes may be amplified in CT scans of the chest and help differentiate sarcoidosis, infective, and malignant diseases causing similar clinical features. A beryllium lymphocyte proliferation test has been described. It can identify prior sensitization to the element. About 1 in 10 sensitized subjects develop chronic beryllium disease.[21] A Chronic Arsenic Intoxication Diagnostic Score has been developed. This evaluation considers the bone As load and several clinical features in quantifying the risk for chronic As toxicity.[22] The detection of heavy metal pollution of water bodies has been revolutionized by quick, accurate, and less labor-intensive real-time biosensors that can aid in controlling community heavy metal toxicity.[23] Toxicogenomic technologies show promise in decoding many of the links between heavy metals and carcinogenicity.[24]

Treatment / Management

The patient is removed from toxic exposure. The heavy metal may be hastened out of the body by gastric lavage, activated charcoal, and skin decontamination. Supportive care can be in the form of intravenous fluids, oxygen, and ventilatory and circulatory support as needed. In severe cases, hemodialysis, plasma exchanges, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may be necessary. Specific therapy to remove the heavy metal is by administering chelating agents, which are metal-binding ligands specific for each metal, forming a ring-structure called a chelate. It is more effective when used in combination with antioxidants.[25]

The properties of an ideal chelating agent are:

- High solubility

- High cell permeability

- Ability to bind most toxic heavy metals and form non-toxic compounds

- Highly effective by oral and parenteral routes

- A high rate of elimination

However, no such ideal chelator exists, and the search is on. Due to several drawbacks of chelating agents, research has focused on plant products that serve such functions. These naturally occurring phytochelatins may offer a cheaper and safer alternative, especially in economically downtrodden nations where the problem is manifold.[26]

- In treating Pb toxicity, DMSA (meso-2,3-dimercaptosuccinic acid) was superior to dimercaprol, also called British anti-Lewisite (BAL) plus calcium ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (CaEDTA). CaEDTA resulted in increased Pb accumulation in various organs, including the brain.

- BAL was ineffective, but a combination of deferasirox and deferiprone was extremely effective in Cd toxicity.[11]

- In As toxicity, the benefits of chelation exceed the side-effects and prevent acute renal failure. 2,3-di-sulfanyl-1-propane sulfonic acid (DMPS) or DMSA are the therapeutic choices. They are more soluble in water than the BAL, and oral administration is effective.

- Sodium diethyldithiocarbamate is useful and effective in Ni toxicity and is superior to D-penicillamine and dimercaprol (BAL).

- DMSA is very effective in Hg toxicity. BAL is contraindicated in this instance because it increases the levels of both iHg and CH3Hg in the brain. Selenium and vitamin E can aid in the treatment of Hg toxicity.[27]

- Extracellular Zn chelation is by CaEDTA. Since this does not cross the blood-brain barrier, intracellular chelators like 1-hydroxy pyridine-2-thione (pyrithione), with a lower affinity for zinc and N, N, N’, N’-tetrakis-(2-pyridyl methyl) ethylene diamine penta-ethylene (TPEN), having a high affinity for zinc ,have been developed. (B3)

Differential Diagnosis

The nervous system involvement may masquerade as dementia, depression, degenerative disease, or peripheral nerve lesions.

- Renal affliction may resemble tubular, interstitial, or glomerular pathology.

- More general symptoms of fatigue, poor appetite, loss of weight, and anemia may lead to confusion with chronic infections or malignancy.

The physical examination findings are not always classical but require diligent investigation:

- Cr VI-induced cutaneous ulcers may be misdiagnosed as chronic arterial or infective ulcers.[28]

- CrVI and/or Cd, along with Ni, can cause nasal septal perforation and confused with a host of other causes like infective, traumatic, and connective tissue problems.[29]

- Acute arsenic toxicity may resemble ciguatera poisoning.[30]

- Chronic mercury toxicity may be confused with pheochromocytoma.[31]

- Lead toxicity may be confused with porphyria.[32] It may also be confused with ADHD in children.

Prognosis

The emphasis should be on prevention. In certain circumstances (industrial exposures, for instance), total prevention is impossible, and minimization of contamination should be the goal. Workers at risk for exposure to heavy metals should take adequate precautions. Management should provide them without any hindrance. Health authorities should supervise the smooth conduct of these measures, and authorities should enforce the law strictly. With minimal exposure and early detection, the prognosis is good. Delayed diagnosis and serious toxicity translate to a bad prognosis. Care of the ill in specialized centers with facilities for testing and treatment may have an edge in managing difficult and serious cases.

The prognosis of heavy metal toxicity at the community level depends on many factors and includes:

- Proper discharge of effluents from factories.

- Periodic inspection of soil and groundwater and measures to remove excess heavy metals like:

- Excavation and removal

- In-situ fixation, including amending the soil

- Phytoremediation (growing certain plants to contain heavy metals) [33][34]

- Soil treatment using asymmetrical alternating current electrochemistry [35]

- Nanomediation is a method to remove toxic heavy metals from the soil and water [36][37]

- A novel method of heavy metal removal from wastewater that is rapid, highly effective, and feasible has been developed. It involves a metal-organic framework/polydopamine composite and may offer solutions to vast polluted waterways, including seawater.[38]

- Regular seawater testing to prevent contamination of fishing areas with heavy metals and inspection of seafood. There are 3 official agencies involved in the regulation of heavy metals:

- The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) sets the heavy metal limits in foods.

- The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) oversees Pb testing in at-risk children.

- The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA): evaluates the effects of heavy metal exposures, regulates industrial emissions, and establishes maximum heavy metal contaminant levels.

Complications

The chelating agents used as a treatment in heavy metal toxicity are not devoid of side effects. Some metal ions are redistributed to other tissues like the brain and thereby increase neurotoxicity. Others chelate essential trace elements and produce a deficiency state, while yet others can cause hepatotoxicity.

Consultations

Diagnosis and management of heavy metal toxicity require strong interdisciplinary collaboration and consultations from an array of specialists depending on the toxicity and presentation

- Primary care (family medicine, internal medicine, pediatric)

- Emergency medicine (adult, pediatric)

- Clinical toxicology

- Laboratory medicine

- Community medicine

- Occupational health

- Clinical psychology/psychiatry/child and adolescent psychiatry

- Clinical pharmacy

- Nursing

- Other subspecialties (nephrology, neurology, gastroenterology, dermatology, endocrinology, and critical care)

- Environmental engineering

Deterrence and Patient Education

Patients and their families should be wary of heavy metal content in many substances like common foods, health foods, and complementary medicine preparations. Particular care is warranted with young children, especially when the family is occupying an older home. Industrial workers and others at risk should receive proper, timely, and periodic screening for toxicity from heavy metals and cooperate with the health authorities. They should take appropriate precautions to prevent or minimize exposure. Health education, in this regard, should be reinforced from time to time. Industries and factories should understand that they have a social responsibility for the proper disposal of wastes and cooperate with the health and other civic authorities.

Pearls and Other Issues

Important facts to keep in mind about heavy metal toxicity include:

- Heavy metal toxicity is underestimated in the community.

- The teaching of heavy metal toxicity is underrepresented in the medical curriculum.

- Heavy metals can cause harm to the environment and living beings, including humans, by direct and indirect means.

- Young children are affected more than adults.

- Affected pregnant women can pass on the toxic heavy metals to the developing fetus and produce much harm.

- The toxicity of heavy metals can be acute and chronic.

- Although classical symptoms and signs for each heavy metal exist, they are not present in every case, and a high index of suspicion is necessary for a correct diagnosis.

- Heavy metals can affect the nervous, pulmonary, cardiovascular, renal, skin, reproductive, and skeletal systems in varying degrees.[39]

- A good history, physical examination, and appropriate laboratory testing of blood, urine, and other tissues can aid with the diagnosis.

- The levels of heavy metals in the blood and urine reflect current exposure and not the true tissue levels; a chelation challenge may be needed.

- Heavy metals cause harm to proteins like enzymes, DNA, and membrane lipids and disrupt normal cellular functions.

- Many body systems can be involved and mimic other diseases that affect those systems.

- If detected and treated early, the prognosis is good.

- Besides removing the offending heavy metals and the patient from the toxic environment, supportive care and chelation therapy are the mainstays.

- Occupational and health regulations require strict enforcement and environmental engineering measures to reduce heavy metal toxicity at the community level.

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

In individual patients presenting with heavy metal toxicity, the primary care physician or the emergency medicine physician is usually the first contact health provider. The the primary care or emergency medicine physician should have a high index of suspicion of heavy metal as the etiology, especially if the clinical picture does not improve with treatment for usual conditions. Primary care often needs consultation from the clinical toxicologist who is an expert in these conditions and advise on the tests and treatments. The laboratory personnel should be provided with a good history to select the specific containers to collect blood, urine, and other tissue specimens to enhance the accuracy of the tests. They also guide the clinician in properly preparing the patient before the tests to avoid confounders from misleading the diagnosis.

In selected cases, care from other specialties/subspecialties may be needed to treat specific organ dysfunction, as discussed under consultations. The clinical pharmacist is vital in guiding the dosing and monitoring of chelation therapy. One should not forget the role played by skilled nurses in the care of patients affected by heavy metal toxicity from primary care in the ambulatory clinic through tertiary care for complicated cases and in the occupational health clinics. Finally, the roles of the occupational health consultant, community medicine physician, and environmental engineer are vital to control heavy metal toxicity in the soil, water, industrial segment, and provide for a healthier society. Proper coordination among all the above providers is essential to reduce the burden and prevent morbidity and mortality from heavy metal toxicity.

Media

(Click Image to Enlarge)

(Click Image to Enlarge)

References

Bolan S, Kunhikrishnan A, Seshadri B, Choppala G, Naidu R, Bolan NS, Ok YS, Zhang M, Li CG, Li F, Noller B, Kirkham MB. Sources, distribution, bioavailability, toxicity, and risk assessment of heavy metal(loid)s in complementary medicines. Environment international. 2017 Nov:108():103-118. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2017.08.005. Epub 2017 Aug 24 [PubMed PMID: 28843139]

Rahman MM, Chowdhury UK, Mukherjee SC, Mondal BK, Paul K, Lodh D, Biswas BK, Chanda CR, Basu GK, Saha KC, Roy S, Das R, Palit SK, Quamruzzaman Q, Chakraborti D. Chronic arsenic toxicity in Bangladesh and West Bengal, India--a review and commentary. Journal of toxicology. Clinical toxicology. 2001:39(7):683-700 [PubMed PMID: 11778666]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAoshima K. [Itai-itai disease: cadmium-induced renal tubular osteomalacia]. Nihon eiseigaku zasshi. Japanese journal of hygiene. 2012:67(4):455-63 [PubMed PMID: 23095355]

Yang AM,Cheng N,Pu HQ,Liu SM,Li JS,Bassig BA,Dai M,Li HY,Hu XB,Ren XW,Zheng TZ,Bai YN, Metal Exposure and Risk of Diabetes and Prediabetes among Chinese Occupational Workers. Biomedical and environmental sciences : BES. 2015 Dec; [PubMed PMID: 26777907]

Kim NH, Hyun YY, Lee KB, Chang Y, Ryu S, Oh KH, Ahn C. Environmental heavy metal exposure and chronic kidney disease in the general population. Journal of Korean medical science. 2015 Mar:30(3):272-7. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2015.30.3.272. Epub 2015 Feb 16 [PubMed PMID: 25729249]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceRehman K, Fatima F, Waheed I, Akash MSH. Prevalence of exposure of heavy metals and their impact on health consequences. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2018 Jan:119(1):157-184. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26234. Epub 2017 Aug 2 [PubMed PMID: 28643849]

Wu X, Cobbina SJ, Mao G, Xu H, Zhang Z, Yang L. A review of toxicity and mechanisms of individual and mixtures of heavy metals in the environment. Environmental science and pollution research international. 2016 May:23(9):8244-59. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-6333-x. Epub 2016 Mar 11 [PubMed PMID: 26965280]

Shen HM, Liu ZG. JNK signaling pathway is a key modulator in cell death mediated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. Free radical biology & medicine. 2006 Mar 15:40(6):928-39 [PubMed PMID: 16540388]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSingh N, Kumar D, Sahu AP. Arsenic in the environment: effects on human health and possible prevention. Journal of environmental biology. 2007 Apr:28(2 Suppl):359-65 [PubMed PMID: 17929751]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceFlora SJ, Mittal M, Mehta A. Heavy metal induced oxidative stress & its possible reversal by chelation therapy. The Indian journal of medical research. 2008 Oct:128(4):501-23 [PubMed PMID: 19106443]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceRafati Rahimzadeh M, Rafati Rahimzadeh M, Kazemi S, Moghadamnia AA. Cadmium toxicity and treatment: An update. Caspian journal of internal medicine. 2017 Summer:8(3):135-145. doi: 10.22088/cjim.8.3.135. Epub [PubMed PMID: 28932363]

Houston MC. Role of mercury toxicity in hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and stroke. Journal of clinical hypertension (Greenwich, Conn.). 2011 Aug:13(8):621-7. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7176.2011.00489.x. Epub 2011 Jul 11 [PubMed PMID: 21806773]

Heyer NJ, Echeverria D, Martin MD, Farin FM, Woods JS. Catechol O-methyltransferase (COMT) VAL158MET functional polymorphism, dental mercury exposure, and self-reported symptoms and mood. Journal of toxicology and environmental health. Part A. 2009:72(9):599-609. doi: 10.1080/15287390802706405. Epub [PubMed PMID: 19296409]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceMalaki M. Acute encephalopathy following the use of aluminum hydroxide in a boy affected with chronic kidney disease. Journal of pediatric neurosciences. 2013 Jan:8(1):81-2. doi: 10.4103/1817-1745.111439. Epub [PubMed PMID: 23772257]

Ratnaike RN. Acute and chronic arsenic toxicity. Postgraduate medical journal. 2003 Jul:79(933):391-6 [PubMed PMID: 12897217]

Balmes JR, Abraham JL, Dweik RA, Fireman E, Fontenot AP, Maier LA, Muller-Quernheim J, Ostiguy G, Pepper LD, Saltini C, Schuler CR, Takaro TK, Wambach PF, ATS Ad Hoc Committee on Beryllium Sensitivity and Chronic Beryllium Disease. An official American Thoracic Society statement: diagnosis and management of beryllium sensitivity and chronic beryllium disease. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2014 Nov 15:190(10):e34-59. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1722ST. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25398119]

Jaishankar M, Tseten T, Anbalagan N, Mathew BB, Beeregowda KN. Toxicity, mechanism and health effects of some heavy metals. Interdisciplinary toxicology. 2014 Jun:7(2):60-72. doi: 10.2478/intox-2014-0009. Epub 2014 Nov 15 [PubMed PMID: 26109881]

Rana MN, Tangpong J, Rahman MM. Toxicodynamics of Lead, Cadmium, Mercury and Arsenic- induced kidney toxicity and treatment strategy: A mini review. Toxicology reports. 2018:5():704-713. doi: 10.1016/j.toxrep.2018.05.012. Epub 2018 May 26 [PubMed PMID: 29992094]

Tchounwou PB, Yedjou CG, Patlolla AK, Sutton DJ. Heavy metal toxicity and the environment. Experientia supplementum (2012). 2012:101():133-64. doi: 10.1007/978-3-7643-8340-4_6. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22945569]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAl Hammouri F, Darwazeh G, Said A, Ghosh RA. Acute thallium poisoning: series of ten cases. Journal of medical toxicology : official journal of the American College of Medical Toxicology. 2011 Dec:7(4):306-11. doi: 10.1007/s13181-011-0165-3. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21735311]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceMiddleton D, Kowalski P. Advances in identifying beryllium sensitization and disease. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2010 Jan:7(1):115-24. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7010115. Epub 2010 Jan 13 [PubMed PMID: 20195436]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDani SU, Walter GF. Chronic arsenic intoxication diagnostic score (CAsIDS). Journal of applied toxicology : JAT. 2018 Jan:38(1):122-144. doi: 10.1002/jat.3512. Epub 2017 Aug 31 [PubMed PMID: 28857213]

Adekunle A, Rickwood C, Tartakovsky B. Online monitoring of heavy metal-related toxicity using flow-through and floating microbial fuel cell biosensors. Environmental monitoring and assessment. 2019 Dec 17:192(1):52. doi: 10.1007/s10661-019-7850-0. Epub 2019 Dec 17 [PubMed PMID: 31848773]

Koedrith P, Kim H, Weon JI, Seo YR. Toxicogenomic approaches for understanding molecular mechanisms of heavy metal mutagenicity and carcinogenicity. International journal of hygiene and environmental health. 2013 Aug:216(5):587-98. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2013.02.010. Epub 2013 Mar 13 [PubMed PMID: 23540489]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceKim JJ, Kim YS, Kumar V. Heavy metal toxicity: An update of chelating therapeutic strategies. Journal of trace elements in medicine and biology : organ of the Society for Minerals and Trace Elements (GMS). 2019 Jul:54():226-231. doi: 10.1016/j.jtemb.2019.05.003. Epub 2019 May 10 [PubMed PMID: 31109617]

Amadi CN, Offor SJ, Frazzoli C, Orisakwe OE. Natural antidotes and management of metal toxicity. Environmental science and pollution research international. 2019 Jun:26(18):18032-18052. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05104-2. Epub 2019 May 11 [PubMed PMID: 31079302]

Ralston NV, Raymond LJ. Dietary selenium's protective effects against methylmercury toxicity. Toxicology. 2010 Nov 28:278(1):112-23. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.06.004. Epub 2010 Jun 16 [PubMed PMID: 20561558]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceShelnutt SR, Goad P, Belsito DV. Dermatological toxicity of hexavalent chromium. Critical reviews in toxicology. 2007 Jun:37(5):375-87 [PubMed PMID: 17612952]

Bolek EC, Erden A, Kulekci C, Kalyoncu U, Karadag O. Rare occupational cause of nasal septum perforation: Nickel exposure. International journal of occupational medicine and environmental health. 2017 Oct 6:30(6):963-967. doi: 10.13075/ijomeh.1896.01019. Epub 2017 Aug 23 [PubMed PMID: 28839290]

Friedman MA, Fernandez M, Backer LC, Dickey RW, Bernstein J, Schrank K, Kibler S, Stephan W, Gribble MO, Bienfang P, Bowen RE, Degrasse S, Flores Quintana HA, Loeffler CR, Weisman R, Blythe D, Berdalet E, Ayyar R, Clarkson-Townsend D, Swajian K, Benner R, Brewer T, Fleming LE. An Updated Review of Ciguatera Fish Poisoning: Clinical, Epidemiological, Environmental, and Public Health Management. Marine drugs. 2017 Mar 14:15(3):. doi: 10.3390/md15030072. Epub 2017 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 28335428]

Level 2 (mid-level) evidenceBernhoft RA. Mercury toxicity and treatment: a review of the literature. Journal of environmental and public health. 2012:2012():460508. doi: 10.1155/2012/460508. Epub 2011 Dec 22 [PubMed PMID: 22235210]

Tsai MT, Huang SY, Cheng SY. Lead Poisoning Can Be Easily Misdiagnosed as Acute Porphyria and Nonspecific Abdominal Pain. Case reports in emergency medicine. 2017:2017():9050713. doi: 10.1155/2017/9050713. Epub 2017 May 29 [PubMed PMID: 28630774]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceLone MI, He ZL, Stoffella PJ, Yang XE. Phytoremediation of heavy metal polluted soils and water: progresses and perspectives. Journal of Zhejiang University. Science. B. 2008 Mar:9(3):210-20. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B0710633. Epub [PubMed PMID: 18357623]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceUsharani B, Vasudevan N. Impact of heavy metal toxicity and constructed wetland system as a tool in remediation. Archives of environmental & occupational health. 2016:71(2):102-10. doi: 10.1080/19338244.2014.988674. Epub 2014 Dec 2 [PubMed PMID: 25454352]

Xu J, Liu C, Hsu PC, Zhao J, Wu T, Tang J, Liu K, Cui Y. Remediation of heavy metal contaminated soil by asymmetrical alternating current electrochemistry. Nature communications. 2019 Jun 4:10(1):2440. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10472-x. Epub 2019 Jun 4 [PubMed PMID: 31164649]

Baragaño D, Forján R, Welte L, Gallego JLR. Nanoremediation of As and metals polluted soils by means of graphene oxide nanoparticles. Scientific reports. 2020 Feb 5:10(1):1896. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58852-4. Epub 2020 Feb 5 [PubMed PMID: 32024880]

Baby R, Saifullah B, Hussein MZ. Carbon Nanomaterials for the Treatment of Heavy Metal-Contaminated Water and Environmental Remediation. Nanoscale research letters. 2019 Nov 11:14(1):341. doi: 10.1186/s11671-019-3167-8. Epub 2019 Nov 11 [PubMed PMID: 31712991]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSun DT, Peng L, Reeder WS, Moosavi SM, Tiana D, Britt DK, Oveisi E, Queen WL. Rapid, Selective Heavy Metal Removal from Water by a Metal-Organic Framework/Polydopamine Composite. ACS central science. 2018 Mar 28:4(3):349-356. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00605. Epub 2018 Mar 14 [PubMed PMID: 29632880]

Rana SV. Perspectives in endocrine toxicity of heavy metals--a review. Biological trace element research. 2014 Jul:160(1):1-14. doi: 10.1007/s12011-014-0023-7. Epub 2014 Jun 6 [PubMed PMID: 24898714]

Level 3 (low-level) evidence