Introduction

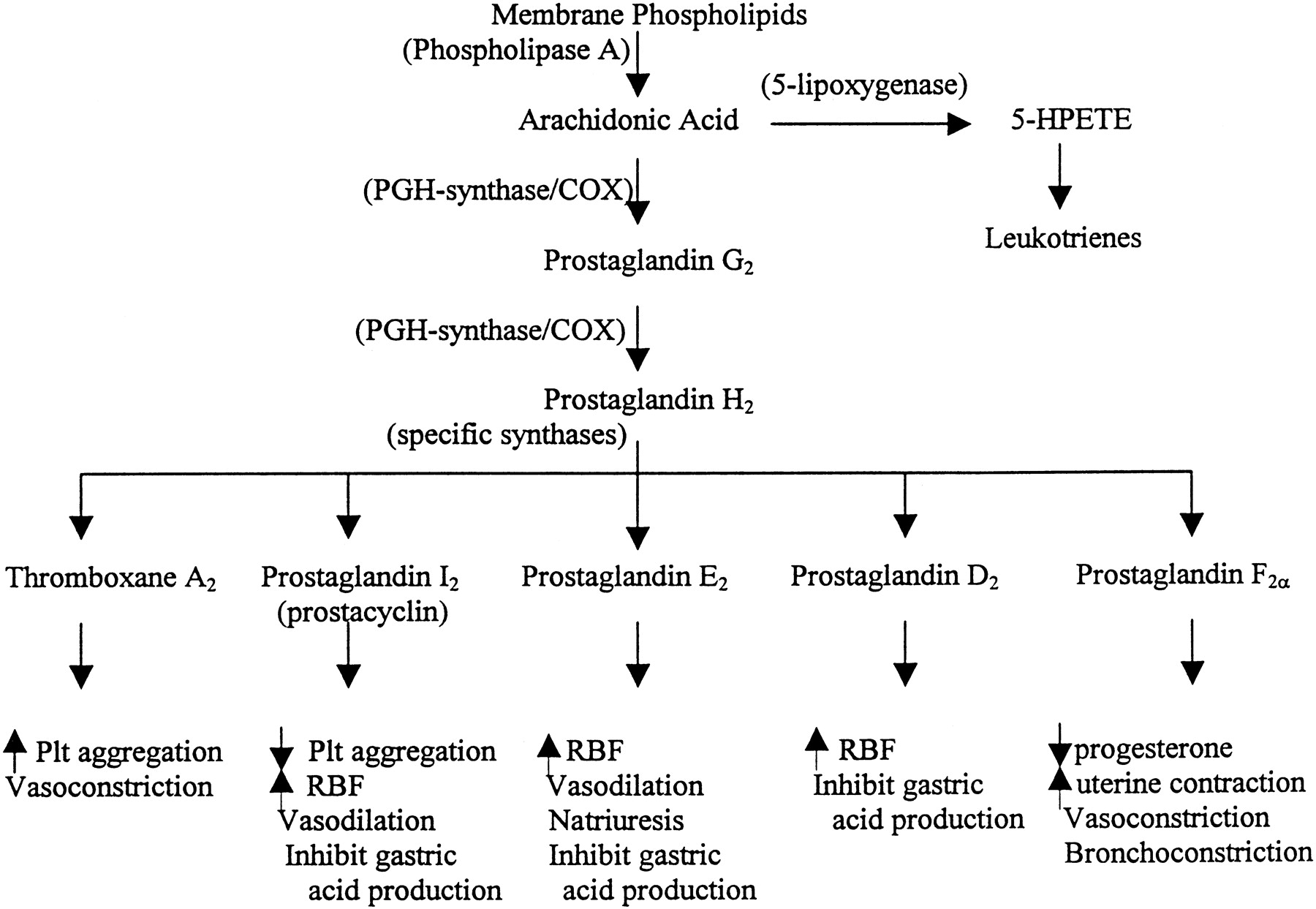

As a class, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, commonly abbreviated as NSAIDs, are chemically varied, yet share similar therapeutic and adverse effects. All drugs within the class work to reduce inflammation, pain, and fever through inhibition of endoperoxide synthesis enzymes, known as cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes. Both cyclooxygenase isozymes, COX-1 and COX-2, convert arachidonic acid into its endoperoxide metabolites, which include prostacyclin, prostaglandins, and thromboxane; these all have diverse biologic activity, ranging from inflammation, smooth muscle tone, and thrombosis. COX-1 is constitutively expressed and is considered the primary source of prostanoids needed for physiologic homeostases, such as protection of gastric epithelium. COX-2, on the other hand, is inducible, and its production of prostanoids is significantly upregulated during conditions of stress and inflammation. Despite the distinct roles of each isozyme, COX-1 and COX-2 can work together, and both contribute to the development of an inflammatory response.[1][2]

Etiology

Register For Free And Read The Full Article

Search engine and full access to all medical articles

10 free questions in your specialty

Free CME/CE Activities

Free daily question in your email

Save favorite articles to your dashboard

Emails offering discounts

Learn more about a Subscription to StatPearls Point-of-Care

Etiology

Most NSAIDs are derived from organic acids and are rapidly absorbed from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. These drugs undergo extensive hepatic metabolism and are excreted through glomerular filtration and tubular secretion. For these reasons, NSAIDs are typically contraindicated in patients with severe hepatic and renal dysfunction. Because NSAIDs are primarily bound to plasma proteins, they easily and quickly accumulate in sites of inflammation so that rapid analgesic relief is provided within 30 to 60 minutes.

Epidemiology

NSAIDs have long been used as safe and effective over-the-counter and prescription formulations for pain relief and fever reduction. It is estimated that 14 million Americans age 45 and older use NSAIDs daily. As the population continues to age, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) expects a marked rise in the use of this drug class that will mirror the expected increased prevalence of painful conditions, such as osteoarthritis and inflammatory diseases. It then comes as no surprise that the rate of adverse events associated with NSAID consumption will also likely escalate. Previous studies have shown that 5% to 7% of hospital admissions result from drug toxicity, with non-aspirin NSAIDs contributing to 11% to 12% of those admissions.[3][4]

Pathophysiology

The mechanisms of action slightly vary depending on the chemical composition of particular agents. Aspirin, derived from salicylic acid, covalently – and therefore, irreversibly – binds to cyclooxygenase, resulting in a conformational change that prevents further metabolism of arachidonic acid. Unlike aspirin, NSAIDs such as ibuprofen, commonly referred to as traditional NSAIDs, reversibly inhibit COX-1 and COX-2, thereby decreasing the synthesis of prostanoids. Even further, a subclass of NSAIDs, inclusive of celecoxib, was developed as selective inhibitors of COX-2 with negligible COX-1 affinity to avoid unwanted GI adverse effects.

NSAIDs are commonly used to manage the pain of low or moderate intensity. These drugs are frequently part of treatment plans for acute musculoskeletal injury, headache, arthralgia, postoperative pain, pain associated with inflammation, and menstrual pain. Prostanoids, such as PGE2, are known effectors of pain and inflammation. The characteristic signs of inflammation, such as rubor, calor, tumor, and dolor, result from increased blood flow and vascular permeability by way of PGE2-mediated arterial dilation, while the perception of pain has been found to be partly due to PGE2’s excitation of peripheral sensory neurons as well as of certain sites within the central nervous system. The antipyretic effects of NSAIDs are due in part to the drug class’ ability to suppress PGE2-triggered hypothalamic elevation of body temperature in response to infection or inflammation. The role of NSAIDs in thrombosis and cardioprotection highlights the particular actions of aspirin in mature platelets where COX-1 is irreversibly inhibited, preventing the generation of thromboxane A2 and its potent effects on platelet activation and vasoconstriction. Aspirin’s irreversibility allows its effects to last the life of the platelet, averaging approximately one week. For this reason, continued doses of aspirin produce a cumulative antiplatelet effect. Aside from these major uses, the therapeutic benefit of NSAIDs is also indicated for other conditions; neonatal cases of patent ductus arteriosus, to increase niacin tolerability, and in rare disorders of upregulated prostaglandin synthesis such as systemic mastocytosis resistant to antihistamines.[5][6][7][8]

Toxicokinetics

As previously described, prostanoids have wide-ranging effects on smooth muscle tonicity within the vasculature, respiratory and GI tracts, reproductive organs, and even on the kidneys. Additionally, thromboxane has specific actions related to platelet function. Therefore, these extensive physiologic consequences impart incredible therapeutic utility upon NSAIDs but may also contribute to the adverse effects and toxicity of this drug class.

Most commonly, the risk of severe GI adverse effects, including ulceration, bleeding, or perforation is increased with NSAID consumption. Though these risks can occur at any time in patients of any age, these adverse events tend to present more commonly in the elderly. Other undesirable GI events may include nausea, dyspepsia, loss of appetite, abdominal pain, and diarrhea from erosion of the alimentary canal. It is well understood that prostanoids such as PGE2 and PGI2 constitutively contribute to GI mucous secretion. Additionally, these prostanoids promote vasodilation, allowing for enhanced blood flow and bicarbonate delivery to mucosal surfaces. Primary inhibition of COX-1 reduces these cytoprotective effects.

Serious cardiovascular adverse events may also be associated with the use of NSAIDs. Historically, much attention had been drawn to the increased incidence of myocardial infarction and stroke, particularly with the selective COX-2 inhibitor rofecoxib, which was removed from the market in 2004. Since then, similar inquiries regarding the cardiovascular safety of the remaining selective COX-2 inhibitor, celecoxib, and non-selective NSAIDs have been investigated. A 2016 study, known as the PRECISION (Prospective Randomized Evaluation of Celecoxib Integrated Safety versus Ibuprofen or Naproxen) trial, provided strong evidence that celecoxib is not associated with a higher rate of cardiovascular events compared to non-selective drugs. However, widely recognized adverse effects include blood pressure elevation and potentiation or exacerbation of congestive heart failure, through inhibition of natural prostanoid-induced salt excretion and changes in renal arteriolar tone. Such risks tend to be dose and duration dependent. Ultimately, it is important to establish that the risk of unfavorable cardiovascular events associated with NSAID use is further increased with tobacco use, alcohol consumption, and generally unhealthy habits.

Less commonly, individuals who consume NSAID medication may experience renal adverse effects. As noted above, NSAIDs have been found to interfere with prostanoid-regulated mechanisms that affect afferent arterioles within nephrons, thereby reducing the glomerular filtration rate. With drug use, the loss of arteriolar dilation opposes prostanoid’s reno-protective effects and increases the risk of acute kidney injury due to decreased renal blood flow. Additional manifestations of NSAID-induced renal toxicity include renal papillary necrosis and interstitial nephritis. The renal papillae are known to be sensitive to the loss of renal blood flow. Ischemic injury from drug-associated vasoconstriction can result in gross hematuria. Interstitial nephritis may occur if individuals are hypersensitive to the analgesic class and due to acute inflammation within the kidney, classically present with eosinophilic pyuria and azotemia.

Aside from these independent toxicities, NSAIDs may also result in adverse effects when taken concurrently with numerous other drugs. As a result of their pharmacokinetics, NSAIDs may interact with other high plasma protein-bound drugs, displacing them and leading to an increase in the free serum concentration of these drugs. Drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, such as warfarin or phenytoin, can theoretically reach toxic levels when displaced in this manner. Additionally, NSAIDs may increase the toxicity of drugs that are dependent on renal clearance (such as lithium) or hepatic metabolism because some NSAIDs reduce renal perfusion and inhibit cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes or glucuronidation.

Other notable drug interactions occur during concurrent use of NSAIDs and antihypertensives, anticoagulants and antiplatelets, selective serotonin receptor inhibitors (SSRIs), and substances that injure GI mucosa. The effects of many antihypertensives are diminished due to the ability of NSAIDs to reduce natriuresis. Besides decreased efficacy, specific use of NSAIDs with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers may exacerbate potassium retention, known to have significant cardiac consequences. Simultaneous use of NSAIDs and anticoagulants or antiplatelets can result in an increased risk of bleeding due to reduced platelet aggregation. Bleeding risk is also similarly increased with concomitant use of SSRIs and NSAIDs, as serotonin is one of many substances taken up by and released from platelets to stimulate aggregation and hemostasis. Lastly, the risk of peptic ulcer disease or a GI bleed is markedly increased when NSAIDs are ingested in combination with alcohol or glucocorticoids which inhibit the activation of the arachidonic acid precursor phospholipase A2.[9][10][11][12][13]

History and Physical

In cases of suspected drug toxicity, the appropriate history must include the specific medication taken, the amount consumed, and the time it was ingested. Additional information, such as potential co-ingestants, is also crucial to the history of the presenting illness to rule out other life-threatening overdoses or drug interactions. Besides an acute change in a patient's mental status, the physical exam is generally unremarkable. Other clinical manifestations may include GI distress, such as nausea and vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness, and blurred vision. However, clinical features of toxicity may depend on other comorbidities that may influence NSAID toxicity. It is imperative that healthcare providers are attentive in history-taking to identify risk factors or comorbidities that may potentiate NSAID adverse effects or possible drug interactions.[14]

Evaluation

After a history and physical have been obtained, evaluation for suspected NSAID toxicity should include pertinent laboratory testing for levels of common co-ingestants such as acetaminophen and salicylate. Other laboratory assessments may be guided by clinical presentation. For instance, a baseline assessment of renal function indicated by blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolyte levels may be useful for symptomatic patients or those who have consumed significantly large amounts (i.e., greater than 6 grams in an adult or greater than 400 milligrams/kilogram in a child) of the drug. If a patient presents with bleeding likely induced by NSAID use, a complete blood count will allow for monitoring of hemoglobin and platelet counts. An arterial blood gas can help determine acid-base status within a patient if there is a concern for massive ingestion, and an electrocardiogram could provide evidence of QT interval prolongation in the setting of potential co-ingestant consumption that may result in dangerous effects on the cardiac conduction system. Last, clinicians must always consider other possible etiologies of altered mental status and may order tests to assess for differential diagnoses such as hypoglycemia.

Treatment / Management

As in any acute condition, patients presenting with acute NSAID toxicity must first be assessed for airway, breathing, and circulation, and all concerns related to a patient's hemodynamic stability must be addressed. Time of ingestion before a presentation is important in determining the need for decontamination, as patients presenting within two hours of consumption may be treated with activated charcoal if no contraindications are present. Otherwise there is no specific antidote formulated for the management of NSAID toxicity, and generally, these scenarios require supportive care, such as correcting electrolyte disturbances, repleting intravascular volume, or correcting acid-base disorders if present. Goals of care for chronic toxicity, on the other hand, involve minimizing exposure or completely eliminating NSAID drugs from a patient's medical regimen if at all possible.

Differential Diagnosis

- Abdominal pain in the elderly patients

- Acute lactic acidosis

- Anxiety disorders

- Chronic anaemia

- Delirium, dementia and amnesia in emergency medicine

- Encephalitis

- Peptic ulcer disease

- Stevens-johnson syndrome

- Toxic epidermal necrolysis

Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

As with most toxicities, the key to management is prevention. If NSAID use is required in patient case management, physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners must aid their patients through medical optimization and reduction in risk factors that contribute to the development of NSAID adverse effects. Additionally, pharmacists are an integral part of the interprofessional team involved in the care of patients with acute or chronic conditions necessitating treatment with NSAIDs. It has been argued that pharmacists within the community are uniquely equipped to educate patients on medication use.[15] Assessing health literacy and counseling patients are naturally complex and require an interprofessional intervention. Nurses as part of the team must be aware of the potential adverse effects and make the members aware if complications such as gastritis develop. (Level III)

Media

References

Morita I. Distinct functions of COX-1 and COX-2. Prostaglandins & other lipid mediators. 2002 Aug:68-69():165-75 [PubMed PMID: 12432916]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceAdelizzi RA. COX-1 and COX-2 in health and disease. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association. 1999 Nov:99(11 Suppl):S7-12 [PubMed PMID: 10643175]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceDavis JS, Lee HY, Kim J, Advani SM, Peng HL, Banfield E, Hawk ET, Chang S, Frazier-Wood AC. Use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in US adults: changes over time and by demographic. Open heart. 2017:4(1):e000550. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2016-000550. Epub 2017 Apr 28 [PubMed PMID: 28674622]

Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ, Farrar K, Park BK, Breckenridge AM. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ (Clinical research ed.). 2004 Jul 3:329(7456):15-9 [PubMed PMID: 15231615]

Verbeeck RK, Blackburn JL, Loewen GR. Clinical pharmacokinetics of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Clinical pharmacokinetics. 1983 Jul-Aug:8(4):297-331 [PubMed PMID: 6352138]

Gong L, Thorn CF, Bertagnolli MM, Grosser T, Altman RB, Klein TE. Celecoxib pathways: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Pharmacogenetics and genomics. 2012 Apr:22(4):310-8. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e32834f94cb. Epub [PubMed PMID: 22336956]

Ricciotti E, FitzGerald GA. Prostaglandins and inflammation. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2011 May:31(5):986-1000. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.207449. Epub [PubMed PMID: 21508345]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceCardet JC, Akin C, Lee MJ. Mastocytosis: update on pharmacotherapy and future directions. Expert opinion on pharmacotherapy. 2013 Oct:14(15):2033-45. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.824424. Epub [PubMed PMID: 24044484]

Level 3 (low-level) evidenceSostres C, Gargallo CJ, Arroyo MT, Lanas A. Adverse effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs, aspirin and coxibs) on upper gastrointestinal tract. Best practice & research. Clinical gastroenterology. 2010 Apr:24(2):121-32. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2009.11.005. Epub [PubMed PMID: 20227026]

Varga Z, Sabzwari SRA, Vargova V. Cardiovascular Risk of Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs: An Under-Recognized Public Health Issue. Cureus. 2017 Apr 8:9(4):e1144. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1144. Epub 2017 Apr 8 [PubMed PMID: 28491485]

Wongrakpanich S, Wongrakpanich A, Melhado K, Rangaswami J. A Comprehensive Review of Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug Use in The Elderly. Aging and disease. 2018 Feb:9(1):143-150. doi: 10.14336/AD.2017.0306. Epub 2018 Feb 1 [PubMed PMID: 29392089]

Weinblatt ME. Drug interactions with non steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Scandinavian journal of rheumatology. Supplement. 1989:83():7-10 [PubMed PMID: 2576330]

Moore N, Pollack C, Butkerait P. Adverse drug reactions and drug-drug interactions with over-the-counter NSAIDs. Therapeutics and clinical risk management. 2015:11():1061-75. doi: 10.2147/TCRM.S79135. Epub 2015 Jul 15 [PubMed PMID: 26203254]

Smolinske SC, Hall AH, Vandenberg SA, Spoerke DG, McBride PV. Toxic effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in overdose. An overview of recent evidence on clinical effects and dose-response relationships. Drug safety. 1990 Jul-Aug:5(4):252-74 [PubMed PMID: 2198051]

Level 3 (low-level) evidencePai AB. Keeping kidneys safe: the pharmacist's role in NSAID avoidance in high-risk patients. Journal of the American Pharmacists Association : JAPhA. 2015 Jan-Feb:55(1):e15-23; quiz e24-5. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2015.15506. Epub [PubMed PMID: 25503987]